Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 3 Sept 2024Fudgy brownies with walnuts

City/Region: Chicago, Illinois

Time Period: 1904I love a gooey, chocolatey brownie, so I opted not to make the first recipe for something called brownies from 1896, because it had no chocolate and instead used molasses. Certainly not the brownies of my heart.

There are a couple of origin stories about brownies, but the one for Bangor brownies goes that a housewife forgot to put baking powder into her chocolate cake. While I question the validity of this story, we do see a lot of recipes for Bangor brownies during the early 20th century that closely resemble brownies today.

While these may not rival my favorite modern ones, they’re very good. They come out fudgy and dense without being heavy and have a surprising amount of chocolate flavor for the amount of chocolate in the recipe. No matter their origin, brownies haven’t changed all that much in the last 120 years.

Bangor Brownies

Cream one-half cup of butter, one cup sugar. Add two squares (one-quarter cake) Baker’s chocolate, melted, two eggs. One half-cup pastry flour and one-half cup chopped walnuts. Spread on baking tins and bake fifteen minutes in a moderate oven.— Service Club Cook Book, 1904

January 14, 2025

Baking the Original Brownie – The History of Brownies

October 20, 2024

The True History of Deep Dish Pizza

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Jul 2, 2024Deep dish cheese pizza with a bready crust

City/Region: Chicago

Time Period: 1945 | 1947The unsung hero of deep dish pizza is a woman named Alice Mae Redmond, who was the head chef at famous pizzerias like Pizzeria Uno and Gino’s. It seems like wherever she went, that was the best pizza place in town. She’s also the one who changed deep dish pizza crust from the bready version in this recipe to a butterier, more biscuit-like version that is found in modern deep dish.

This crust is still delicious, and the sauce is super flavorful. Be sure to cook the sauce down enough so that it’s nice and thick (mine was a bit too watery for my taste). In the 1940s, you could get cheese OR anchovies OR sausage, but not any of them together. I made a cheese pizza with my preferred ratio of about 50/50 cheese to sauce, but feel free to change things up however you like. You could even add more than one topping, though it won’t be quite as historically accurate.

(more…)

July 15, 2024

From Utica to Chicago, then on to New Orleans

A.M. Hickman takes Amtrak on a pre-wedding rail tour of the United States. We pick up the narrative in Utica, New York, whose Amtrak station apparently gives off a North Korean/Potemkin village vibe:

The gargantuan marble-columned Utica train station sleeps like silver spoons in a dusty drawer of a great house. The bones of Utica have the smell and patina of old finery laid out at an estate sale in a great and crumbling chateau; its patrons long dead or doddering — if one walks quietly, they can hear their ghosts. I sip a porter at the trackside pub, staring out into the maze of empty streets as the pub’s speakers play the song “Allstar”, an upbeat tune released in 1999 by the one-hit-wonder band Smashmouth. And the barkeep looks as if the year 1999 never ended; cigarette smoke curling around his blonde frosted tip hairdo, leaning against the brick walls of the tavern’s courtyard in his sunglasses and FUBU-brand track jacket, kicking at the dirt in his stained white Reeboks.

No one else is at the bar — one wonders if Utica is being maintained in North Korean style, subsidized by the state to keep up appearances, spray-painted to the “uncanny valley” hue of sham vitality lest a train passenger should step off for a smoke break and start asking too many questions. I ponder this as the song continues — “Hey now, you’re an All-star, get your game on on, go play // hey now, you’re a rockstar, get the show on, get paid …” The barkeep ashes his cigarette and glowers, casting furtive glances toward the empty bar. I pay the tab, glad to be departing this weird, empty place in the heart of American Pyongyang — where one gets the disturbing sense that they may be being watched.

The train arrives, and Keturah is with me. If Amtrak’s Lake Shore Limited were one’s first introduction to the Amtrak system they might get the impression that it’s a long, metal, track-bound Greyhound bus. The passengers are sullen and bored with earbuds universally donned. Cheerio dust covers our seat, and a heavy-set hustler-looking character in an Eminem t-shirt is sawing wood, snoring deeply, displaying all of the textbook symptoms of undiagnosed sleep apnea. Worst of all, the train’s bright white lights — the sorts of fluorescent lights one sees inside of hospitals and Wal-Marts — stay on all night, angled directly into our eyes, and we fitfully sleep as the train rattles at 110mph all the way to Chicago. The trip takes fifteen hours.

For Keturah and I, this ride is our last bit of time together before separating for a month. We’d both been taken with the romantic idea of parting ways for a few weeks before our wedding — and at Chicago, she’d head to southern Illinois to see her great-grandmother, and I’d jump aboard the City of New Orleans train to soak in the sinful humidity of the Crescent City. From there, I’d run a nearly 8,000-mile circuit around the United States — and if the trains ran on time, I’d arrive at our wedding in Upstate New York on time. Sleepy-eyed and rueing our separation, I saw her off onto her train.

I wandered Chicago’s Union Station alone, rattled by the gravity of her absence already, and several hours later, I hopped onto my own southbound train, dreaming of the woman who would become my wife.

A “vibe shift” takes place as I step aboard The City of New Orleans. The workers are a jazzy bunch, obviously natives of the city below sea level, all of them jocular and energetic; smooth Louisiana tones drip from their smiling craws — “good evening baby, we don’t mind you playing music in the cafe car — but if it’s the nighttime hours it had bettuh be smooth!”

Unlike the Lake Shore Limited, this train is equipped with a “Superliner” viewer car with domed glass windows that afford passengers views of the scenery. Most long-distance routes are equipped with these — except the routes that go in and out of New York City, as the train tunnels there don’t have the clearance for these tall double-decker cars. But the view of the scenery doesn’t matter much on the ride south through Illinois and Mississippi. This stretch of track is, in the colorful words of one especially talkative train attendant, “a damned old tunnel of green trees and shit“. Nonetheless this “tunnel” had a soothing effect as we sped southward, and I crawled down under the Superliner’s benches to sleep.

In New Orleans, I had the great pleasure of staying with one C. Sandbatch, a native son of New Orleans, and Covington, and Mississippi, and Kentucky, and, well — practically every location in the American South but Alabama or Georgia. A polymath of Southern geography, history, and literature, Mr. Sandbatch quite naturally opened his home to me, offering the air mattress in his high-ceilinged back room as organically as the forest offers its glens and creek-beds to a transient jackrabbit or wren. And quite naturally, he stationed himself upon the porch of his sparsely-decorated shotgun shack house, musing on his weirder years, relating tales of corrupt Parish Presidents and bayou dramas, and offering reflections on the more nuanced elements of Deep South race relations, New Orleans musical genre-bending, and Southern ecology.

Leaning back onto the wood of the old porch — which had been under some eleven feet of water during Hurricane Katrina — I listened to him speak in slow, eloquent tones as the breeze rustled the palms on the street. His cigarette smoke hung above the sleepy-eyed cats, and the wine in my cup was lukewarm in the humidity. We drove all over the city in his ailing old jeep, a vehicle whose transmission had the habit of “burping” in traffic, and we flitted in and out of cafes and bars, each of which seemed to be a sort of checkpoint in Mr. Sandbatch’s memory. Wistfully he drank as he spoke, and I felt myself slipping into the ease one knows only when wandering a city with one of its own sons.

November 23, 2023

QotD: The Austrian and Chicago schools of economics

[Bureaucracies will always expand far beyond the “problem” they were instituted to address] was, anyway, the view of that “Austrian school economist”, Ludwig von Mises, proponent like the rest in that school of “classical liberalism”. His hatred of bureaucracy was a wonderful, animated thing. In his great book, Human Action, and many others, he could become almost boring on the topic. What distinguishes the Austrian school from, say, the famous Chicago school of Milton Friedman and his ilk, was its European origin. (They were, however, consciously allied.) The “Austrians” go back, to Catholic antecedents, and their interests are not reducible to “pure economics” (scare quotes because there is no such thing). Over time it extended to broad social questions, and through a constant interest in the history of ideas. These were multilingual and multicultural, in the manner of the old Habsburg empire; where our American classical liberalism has been almost unilingually English, provincially distrustful of foreign thinkers, and buzzing with statistics. (You’ll need a degree in math.)

War propelled the “Austrian” thinkers westward, and the fall of the Berlin wall propelled the “Chicago” school east. The terms no longer have geographical significance.

What all classical liberals have in common is the passionate vindication and defence of human freedom. That is what makes them, unlike progressives, readable in subsequent generations. Their subject matter cannot become dated. The “Austrians” are also necessary to understand modern history, positively as well as negatively, in the evolution of, for instance, the Christian Democratic movement that conceived a peaceful post-war Europe, in defiance of secularizing bureaucratic trends and mass-man “ideals”. Alas, this was overall defeated by the Eurocratic trend-setters, determined to build a magnificent autocratic monument to themselves.

I have the most enchanting memory of opening the box that contained an American reprint of Human Action (big thick book), which I had ordered at the age of fifteen. I no longer own a copy, but gather it still stands as a monument to the resistance — a study of “praxeology”, or purposeful human choices, stretching so wide that even religion and morality could be touched. (Conventional economics has no time for either.) A half-century later, I can even remember the construction of an earnest reading list, that was soon abandoned when I went on the road.

One may see the great division in Western thought and politics, which the Austrian-school Friedrich Hayek traced back to Bacon and Descartes, and can be traced farther to the Nominalists of the later Middle Ages. Humans live in freedom and make choices, to be restrained only by the plainest moral codes. Or, by the alternative thesis, we are components of a machine, which the man with Power can monkey with, by implanting stimuli here and there.

We are creatures of God, or — we are replaceable parts in a bureaucracy.

David Warren, “Austrian schoolboy”, Essays in Idleness, 2019-09-17.

May 6, 2023

History Summarized: Chicago’s Tribune Tower

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 20 Jan 2023It’s not a Dome, but it’s still pretty darn good.

(more…)

January 11, 2023

Al Capone’s Soup Kitchen

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 10 Jan 2023

(more…)

December 16, 2021

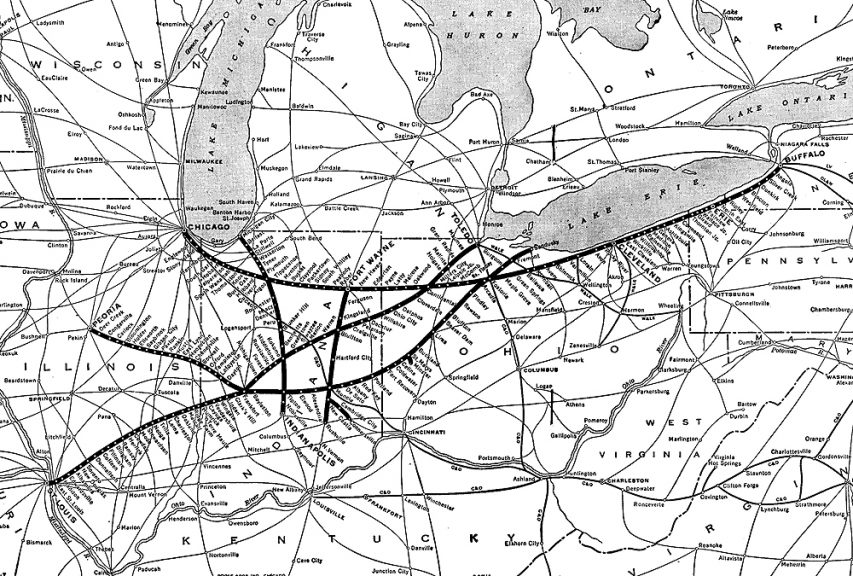

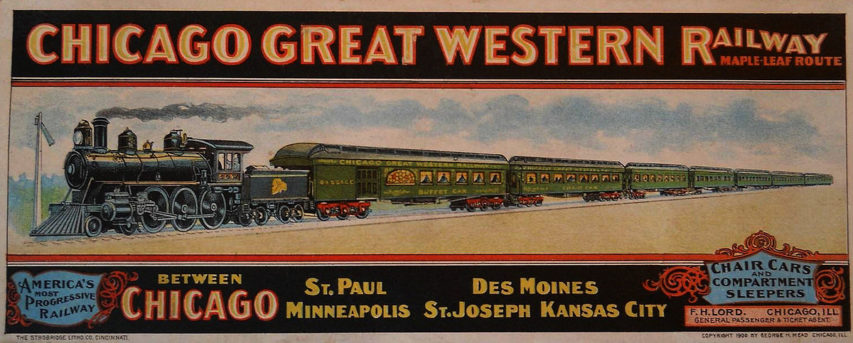

Fallen Flag — the Chicago Great Western Railroad

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Chicago Great Western Railroad (CGW) by H. Roger Grant. Not being over-familiar with the US Midwest, while I’d heard of this railway I had no real background knowledge about it. The earliest charter was granted to the Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Airline in 1835, but no construction took place under the original management and the charter rights were passed on to the Minnesota and North Western Railroad (M&NW) in 1854. Actual construction of the line did not begin until 1884, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota with Dubuque, Iowa. The M&NW was taken over by the Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railroad under the control of Alpheus Beede Stickney, a St. Paul businessman. By 1892, when the system adopted the Chicago Great Western name, there were routes to Omaha, Nebraska, St. Joseph, Missouri and Chicago.

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Chicago Great Western Railroad (CGW) by H. Roger Grant. Not being over-familiar with the US Midwest, while I’d heard of this railway I had no real background knowledge about it. The earliest charter was granted to the Chicago, St. Charles & Mississippi Airline in 1835, but no construction took place under the original management and the charter rights were passed on to the Minnesota and North Western Railroad (M&NW) in 1854. Actual construction of the line did not begin until 1884, connecting St. Paul, Minnesota with Dubuque, Iowa. The M&NW was taken over by the Chicago, St. Paul & Kansas City Railroad under the control of Alpheus Beede Stickney, a St. Paul businessman. By 1892, when the system adopted the Chicago Great Western name, there were routes to Omaha, Nebraska, St. Joseph, Missouri and Chicago.

The Panic of 1907 ended Stickney’s control of the railway and it ended up in the hands of J.P. Morgan:

Even though Stickney had imaginatively assembled a Midwestern trunk line, he ultimately lost his railroad. The brief but severe Bankers’ Panic of 1907 threw CGW into receivership, a fate the company had avoided during the much more severe Panic of 1893. The nation’s financial wizard, J.P. Morgan, took control, and in 1909 a reorganized Chicago Great Western Railroad made its debut. Morgan wisely placed Samuel Morse Felton in charge, because the new president excelled as a railroad manager. His greatest triumph before joining the Great Western had been to turn the Chicago & Alton into a profitable property.

[…]

The Felton years in Chicago Great Western railroad history resulted in a rehabilitated physical plant. Changes in rolling stock caught the attention of thousands of on-line residents. In 1910, for example, CGW purchased 10 Baldwin 2-6-6-2 Mallets (“Snakes”, as employees called them), and the road’s own shop forces at Oelwein, Iowa, rebuilt three F-3 class 2-6-2s (CGW had 95 total Prairie types) into three more 2-6-6-2s. Unfortunately, these giants did not work out, and in 1916 the Baldwins were sold to the Clinchfield and the homebuilds were rebuilt into 4-6-2s. In the Mallets’ place appeared reliable yet powerful 2-8-2s, of which CGW owned 35.

The railroad became a leader in the use of gasoline and later diesel motive power. Before World War I CGW assembled a small fleet of McKeen motor cars, knife-nosed “wind-splitters” that replaced steam-powered branchline and local trains. Its 1924 gas-electric car M-300 was the first unit of any type sold by the Electro-Motive Co., and it helped replace steam on trains 3 and 4 on the 509-mile Chicago–Omaha run. In 1929 CGW remodeled three McKeens to make up a deluxe gas-electric train, the Minneapolis–Rochester (Minn.) Blue Bird. CGW was mostly satisfied with its pioneering internal-combustion equipment.

1906 advertising blotter for the Chicago Great Western Railroad’s passenger trains.

Wikimedia Commons.

CGW’s independent life came to an end in the same era as a lot of small to medium sized railways disappeared into corporate mergers, take-overs, or bankruptcy:

Being a small road in an era when competitors were expanding through mergers led to the corporate demise of the CGW. Saying that shareholders “must be protected”, the board sought a partner. Although the expectation was union with KCS or perhaps the Soo Line, the aggressive Chicago & North Western, headed by resourceful Ben W. Heineman, made an acceptable proposal, and in 1968 Chicago Great Western Railroad history ended with it becoming a Fallen Flag.

C&NW operated CGW switchers and F units for a short time, and assimilated Great Western’s only second generation diesels — eight GP30s and nine SD40s, all painted in the final solid “Deramus red” seen also on KCS and Katy — into the yellow fleet.

Although for a short time much of the former Great Western maintained its identity as C&NW’s Missouri Division, that operating organization ended and its lines started to disappear. By the 1980s much of the trackage had been retired, and at the start of the 21st century only about 145 miles remained. Survivors include portions of the main lines in Iowa (Mason City to the Fort Dodge area; Oelwein–Waterloo; and a leg into Council Bluffs); the Cannon Falls (Minn.) branch; and terminal trackage around South St. Paul, Minn., and just west of Chicago.

November 4, 2021

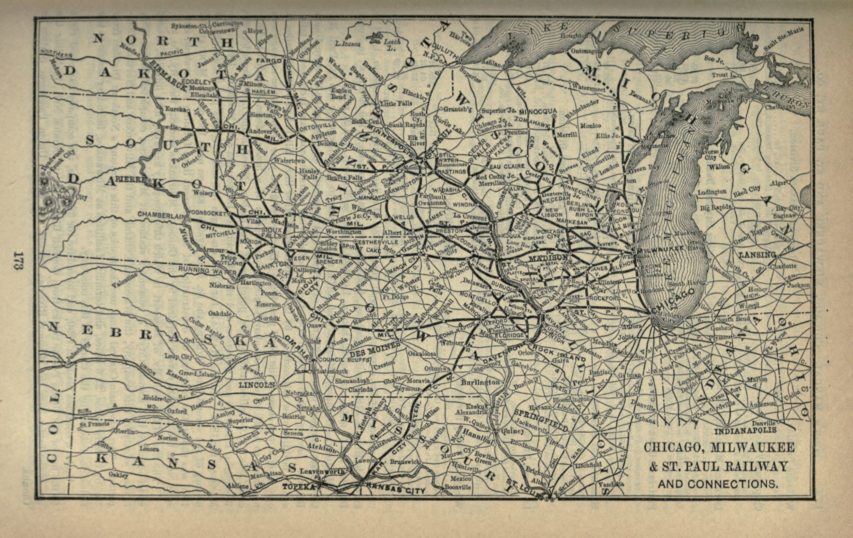

Fallen Flag — the Milwaukee Road

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Milwaukee Road (MILW) by George Drury. As with most major US railways, the Milwaukee Road was a long-term collection of different railway lines, some merged for obvious economic benefit and others taken over to reduce competition, but the first of the components that eventually evolved into the Milwaukee Road system was the 1847 Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad. This line was incorporated to connect the Wisconsin city of Milwaukee to the river traffic along the Mississippi River, and the corporate name was changed even before construction began to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad to more adequately convey the purpose of the line. The first segment opened in November 1850 connecting Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, a distance of five miles, then to Waukesha a few months later, then to Madison, but not extending all the way to the river at Prairie du Chien until 1857.

This month’s Classic Trains fallen flag feature is the Milwaukee Road (MILW) by George Drury. As with most major US railways, the Milwaukee Road was a long-term collection of different railway lines, some merged for obvious economic benefit and others taken over to reduce competition, but the first of the components that eventually evolved into the Milwaukee Road system was the 1847 Milwaukee and Waukesha Railroad. This line was incorporated to connect the Wisconsin city of Milwaukee to the river traffic along the Mississippi River, and the corporate name was changed even before construction began to the Milwaukee and Mississippi Railroad to more adequately convey the purpose of the line. The first segment opened in November 1850 connecting Milwaukee and Wauwatosa, a distance of five miles, then to Waukesha a few months later, then to Madison, but not extending all the way to the river at Prairie du Chien until 1857.

In that year, another of the frequent financial crises of the era struck and the company struggled on for two years, but eventually went into receivership in 1859. New owner the Milwaukee and Prairie du Chien Railroad took possession in 1861. After the Civil War, the company was merged with the Milwaukee and St. Paul and in 1874 the combined railroad became known as the Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul with the completion of a new line connecting with Chicago.

In the next few years the road built or bought lines from Racine, Wis., to Moline, Ill.; from Chicago to Savanna, Ill., and two lines west across southern Minnesota. The road reached Council Bluffs, Iowa, across the Missouri River from Omaha, in 1882, and reached Kansas City in 1887. In 1893 the CM&StP acquired the Milwaukee & Northern, which reached from Milwaukee into Michigan’s upper peninsula.

In 1900 the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul was considered one of the most prosperous, progressive, and enterprising railroads in the U.S. Its lines reached from Chicago to Minneapolis, Omaha, and Kansas City. Secondary lines and branches covered most of the area between the Omaha and Minneapolis lines in Wisconsin, Iowa, and Minnesota. Lines covered much of eastern South Dakota and reached the Missouri River at three places in that state: Running Water, Chamberlain, and Evarts. Except for the last few miles into Kansas City and operation over Union Pacific rails from Council Bluffs to Omaha, the Missouri River formed the western boundary of the CM&StP. (“Milwaukee Road” as a name or nickname did not come into use until the late 1920s; “St. Paul Road” was sometimes used as a nickname, but the railroad’s advertising used the full name).

The Chicago, Milwaukee and St. Paul Railway in 1893.

Poor’s Manual of the Railroads of the United States via Wikimedia Commons.

The battle over control of the Northern Pacific and the Burlington in 1901 made the Milwaukee Road aware that without its own route to the Pacific it would be at its competitors’ mercy. At the same time the Milwaukee Road was experiencing a change in its traffic from dominance by wheat to a more balanced mix of agricultural and industrial products. Arguments against extension westward included the possibility of the construction of the Panama Canal and the presence of strong competing railroads: Union Pacific, Northern Pacific, and Great Northern. Arguments for the extension banked heavily on the growth of traffic to and from the Pacific Northwest.

In 1901 the president of the Milwaukee Road dispatched an engineer west to estimate the cost of duplicating Northern Pacific’s line. His figure was $45 million. Such an expenditure required considerable thought; not until November 1905 did Milwaukee’s board of directors authorize construction of a line west to Tacoma and Seattle.

In 1905 and ’06 the Milwaukee Road incorporated subsidiaries in South Dakota, Montana, Idaho, and Washington. The Washington company was renamed the Chicago, Milwaukee & Puget Sound Railway, and it took over the other three companies in 1908. It was absorbed by the CM&StP in 1912.

The extension began with a bridge across the Missouri River at Mobridge, 3 miles upstream from Evarts, S.D. Roadbed and rails pushed out from several points into unpopulated territory. The work went quickly, and the road was open to Butte, Mont., in August 1908.

Unfortunately for the Milwaukee, the Pacific extension was much more expensive to build than the initial estimates (it jumped from $45 million in the 1901 survey to $60 million in 1905), eventually weighing down the company books with $257 million in debt and worse, the traffic estimates for the new line turned out to be wildly optimistic. The difficulties of operating steam locomotives across the extension in winter pushed the railway toward electrification as an efficiency and cost-saving move. Beginning in 1914, sections of the line were converted to overhead catenary power until a total of 645 route-miles were being operated with electric locomotives, reportedly saving the company over a million dollars per year.

A Milwaukee “Little Joe” electric locomotive hauling a freight train along the Pacific extension in 1941. The “Little Joe” locomotives were originally built for the Soviet Union in the late 1940s but the US government cancelled the export license as relations with the Soviets deteriorated and the Cold War escalated. The Milwaukee Road bought 12 of the 20 from General Electric for $1 million during the Korean War.

Wikimedia Commons.

Despite the savings through electrification, the Pacific extension drove the company into bankruptcy in 1925, re-emerging as the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, but the new company also had to declare bankruptcy during the Great Depression. Trustees ran the railroad for ten years until renewed civilian traffic after World War 2 allowed normal operations to resume. As with most North American railroads, the good times didn’t last and by the late 1950s, the Milwaukee’s management were looking for a merger partner to help cut costs and shed unprofitable branch lines. Unlike the rival merger of of Northern Pacific, Great Northern, Burlington Route, and the Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway into Burlington Northern, the ICC blocked a merger between the Milwaukee Road and the Chicago and North Western. The ICC also blocked a later application for the Milwaukee to be included in the Union Pacific/Rock Island merger.

With declining business, deferred maintenance issues on most lines, and some self-induced financial issues caused by selling off rolling stock and leasing it back (which exacerbated car shortages leading to further reductions in business), the company had no funds to replace the failing “Little Joe” locomotives on the Pacific extension, so electrification was abandoned in 1974. George Drury sums up the mistakes that led to the end:

Over the decades, the road’s management had made too many wrong decisions: building the Pacific Extension, not electrifying between the two electrified portions, purchasing the line into Indiana, and in the 1960s choosing Flexivans (containers with separate wheels/bogies that required special flatcars) instead of conventional piggyback trailers.

After several money-losing years in the early 1970s, the Milwaukee voluntarily entered reorganization once again on December 19, 1977. The major result of the 1977 reorganization was the amputation of everything west of Miles City, Mont., to concentrate on what became known as the “Milwaukee II” system linking Chicago, Kansas City, Minneapolis-St. Paul, Duluth (on Burlington Northern rails from St. Paul), and Louisville (but no longer Omaha).

By 1983 the Milwaukee’s system consisted of the Chicago–Twin Cities main line; Chicago–Savanna–Kansas City; Chicago–Louisville (almost entirely on Conrail and Seaboard System rails), Milwaukee–Green Bay; New Lisbon–Tomahawk, Wis.; Savanna–La Crosse, along the west bank of the Mississippi; Marquette to Sheldon, Iowa, and Jackson, Minn.; Austin, Minn.–St. Paul; and St. Paul–Ortonville, Minn., plus a few branches.

Three roads vied for what remained of the Milwaukee: the Chicago & North Western, financially none too solid itself; Canadian National subsidiary Grand Trunk Western, with an eye toward creating a route between eastern and western Canada south of the Great Lakes; and Canadian Pacific subsidiary Soo Line.

September 23, 2021

Nazi Fanatics and Gangland Executions | B2W: ZEITGEIST! I E.26 Winter 1925

TimeGhost History

Publisheed 22 Sep 2021The winter of 1925 is a season of gun battles and assassinations. Al Capone is fighting both the Chicago police and rival gangs to gain control of the bootlegging racket, and a Nazi party fanatic murders a Viennese author for his writings on anti-Semitism and eroticism. It’s not all violence, though. This season, a landmark documentary film is released.

(more…)

July 8, 2021

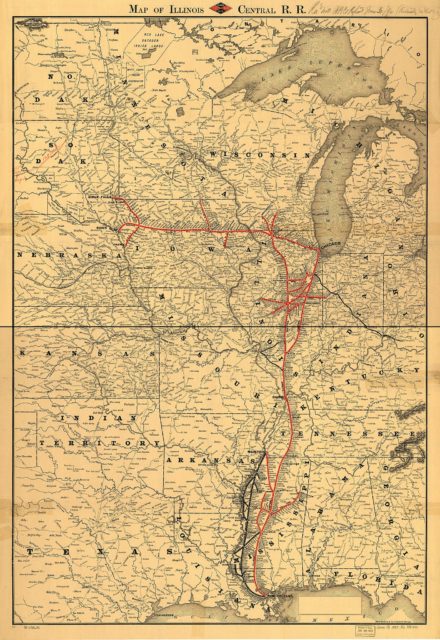

Fallen Flag — the Illinois Central Railroad

The IC (nicknamed the “Main Line of Mid-America”) was originally incorporated in 1836 to build a rail connection from Cairo to Galena with a branch to Chicago, but didn’t receive federal support until 1850 and the company was finally granted a charter in 1851. The IC was the first “land grant” railroad in the United States, and prominent Illinois politicians were deeply involved in the railroad (Senator Stephen Douglas and future President Abraham Lincoln). The line was completed in 1856 and the “branch” to Chicago rapidly became the busiest portion of the line. After the Civil War, the IC expanded out of Illinois into Iowa and then by acquisition and consolidation eventually reached Louisville, Kentucky and New Orleans, Louisiana with many branches and secondary lines throughout the eastern half of the Mississippi valley. In the 1880s, the IC also expanded north and west, reaching locations in Wisconsin, South Dakota, and Nebraska by the end of the century.

During the 1880s, the IC came under the control of E.H. Harriman and as a result were one of the railroads that were involved in the union actions that ran from 1911 until 1915. The IC and the other Harriman-controlled railways had existing contracts with the individual trade unions representing workers on each line, but the unions hoped to force the railways to recognize a “System Federation” of the separate unions that would negotiate as a single unit. The IC refused and hired strikebreakers to fill the positions vacated by striking union members — including many African-American men who would not normally have been allowed to work in those positions on southern railways. Sporadic violence in 1911 and 1912 resulted in the deaths of at least 12 men and 30 others were killed in a steam locomotive boiler explosion in San Antonio, Texas. It was generally seen as a failure by mid-1912, but the strike didn’t formally end until 1915. The unions tried again in 1922 in the Great Railroad Strike, which was an even larger attempt by the unions to operate as a single bargaining unit, and another ten people were killed during the conflict but it lasted only a couple of months and failed to achieve its aims.

Although the major portions of the system were in place by World War 1, there were some additional lines added through to the 1960s, merging or acquiring control of lines like the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley, the Gulf & Ship Island, the Chicago, St. Louis & New Orleans, the Alabama & Vicksburg, and the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific. George Drury picks up the story in mid-century:

In the 1950s and early ’60s IC purchased several short lines: former interurban Waterloo, Cedar Falls & Northern (jointly with the Rock Island through a new subsidiary, Waterloo Railroad); Tremont & Gulf in Louisiana; Peabody Short Line, a coal-hauler at East St. Louis, Ill.; and Louisiana Midland.

In 1968 Illinois Central acquired the western third — Nashville to Hopkinsville, Ky. — of the Tennessee Central when that financially ailing line was split among IC, Louisville & Nashville, and Southern.

Illinois Central Gulf

Illinois Central and parallel Gulf, Mobile & Ohio merged on August 10, 1972, to create the Illinois Central Gulf Railroad, a wholly owned subsidiary of Illinois Central Industries. GM&O was a likely merger partner for Illinois Central, as it was a north-south railroad through much the same area as IC. As part of the merger, ICG took over three Mississippi lines: Bonhomie & Hattiesburg Southern; Columbus & Greenville; and Fernwood, Columbia & Gulf.

The north-south lines of ICG’s map resembled an hourglass. Driving across Mississippi or Illinois from east to west, you could encounter as many as eight ICG lines. The former IC system converged at Fulton, Ky., and the former GM&O main line was less than 10 miles west of Fulton at Cayce.

[…]

On Feb. 29, 1988, the railroad changed its name back to Illinois Central, having divested itself of nearly all the former GM&O routes it acquired in 1972, when it added “Gulf” to its name. At the end of 1988 the Whitman Corp. (formerly IC Industries) spun off the railroad, which then dropped “Gulf” from the name, and in August 1989 control of the railroad was gained by the Prospect Group, which formerly controlled spinoff MidSouth Rail.

IC managers eventually turned their eyes west, to the Chicago, Central & Pacific, which it had sold in 1985. It saw CC&P’s route as a source of grain traffic and perhaps a way to get some of the coal moving east from Wyoming. In June 1996 IC purchased the CC&P. The line remains active.

In February 1998 Canadian National Railway agreed to purchase the IC, creating a 19,000-mile railroad. CN absorbed IC in July 1999, and IC lost its own identity within the CN system.

June 25, 2021

The Birth of the Manhattan Project – WW2 Special

World War Two

Published 24 Jun 2021When nuclear fission was discovered, scientists theorized it could be used in an atomic bomb. Thus, the American Army sets up one of the biggest research projects in history: The Manhattan Project.

(more…)

April 22, 2021

Al Capone, Prohibition, and the American Dream | B2W: ZEITGEIST! I E.16 – Summer 1922

TimeGhost History

Published 21 Apr 2021The Prohibition era is still just getting started, but criminal enterprises have already sprung up everywhere to supply thirsty Americans with their drink. In the “summer of sin” of 1922, one man in particular is making waves in the Chicago underworld.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Francis van Berkel

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Francis van Berkel and Lewis Braithwaite

Image Research by: Daniel Weiss

Edited by: Daniel Weiss

Sound design: Marek KamińskiColorizations:

Daniel Weiss – https://www.facebook.com/TheYankeeCol…Sources:

Library of CongressSoundtracks from Epidemic Sound

– “One More for the Road” – Golden Age Radio

– “London” – Howard Harper-Barnes

– “Infinity Pool & Pool Tables” – Mythical Score Society

– “Rush of Blood” – Reynard Seidel

– “It’s Not a Game” – Philip Ayers

– “Please Hear Me Out STEMS INSTRUMENTS” – Philip Ayers

– “Not Safe Yet” – Gunnar Johnsen

– “On the Edge of Change” – Brightarm Orchestra

– “British Royalty” – Trailer Worx

– “Break Free” – Fabien Tell

– “Steps in Time” – Golden Age Radio

– “Magnificent March 3” – Johannes BornlöfArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

3 days ago

As you hopefully realized from the title, thumbnail, description, and first words coming out of Indy’s mouth, a big focus of this episode is the beginning of the gangland Prohibition era and the rise of Al Capone.It’s a fascinating topic, but something else to draw attention to in this episode is the Catholic Church’s campaign against modernity. Last episode we saw how religion was forced into retreat by the Bolshevik regime in Russia, well this episode we’re seeing one of the oldest religious institutions in the world make its fightback. It shows that the story of modernity isn’t just “old things” fading away and being replaced by “new things”. Instead, it is a story of continual tension, negotiation, and adaption, between the old and the new.

Anyway, philosophical musings on religion aside, this really is an exciting episode and there will be much more on Al Capone and the Beer War in years to come.

November 19, 2020

White Lives Matter More – A Summer of Blood | BETWEEN 2 WARS: ZEITGEIST! | E.04 – Summer 1919

TimeGhost History

Published 18 Nov 2020Technology promises a better and more connected world in the summer of 1919. But battles still rage everywhere over who will inherit it.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Subscribe to our World War Two series: https://www.youtube.com/c/worldwartwo…

Like TimeGhost on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/TimeGhost-16…Hosted by: Indy Neidell

Written by: Indy Neidell and Francis van Berkel

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Maria Kyhle

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Indy Neidell and Francis van Berkel

Image Research by: Miki Cackowski and Michał Zbojna

Edited by: Michał Zbojna

Sound design: Marek KamińskiColorizations:

Mikołaj Uchman

Spartacus OlssonSources:

From the Noun Project: bridge by Adrien Coquet, Delete by Kevin Eichhorn, Fire by Sweet Farm, Model T by Alex Valdivia, people by Anastasia Latysheva, peoples by Musmellow, revolt by Symbolon, Smoke by Krish, people by Nithinan Tatah, explosion by Aldric RodríguezArchive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

TimeGhost History

21 hours ago

Four episodes into this new series and we think it’s going pretty well. Behind-the-scenes we have been getting ahead with our planning to make make things as laser-focused as possible and we have some pretty fascinating pieces of history we want to talk about.But we know that there is always a learning curve with a new series and we care what our community thinks. It’s the TimeGhost Army who make our content possible so we’d like to hear from you what you think about Season Two of Between 2 Wars. What are you enjoying about it? Is there anything you think we should work on? How do you feel about Indy’s outrageous suits and ties?

October 19, 2020

QotD: Afflicting the comfortable

In 1893, Finley Peter Dunne, a journalist-turned-humorist at the Chicago Evening Post, introduced Martin J. Dooley to the people of Chicago. Mr. Dooley, as he was best known, was a thick-accented bartender from Ireland who owned a tavern in the Bridgeport neighborhood. Mr. Dooley became popular among Chicagoans for his rich satire of politics and society. Of course, Mr. Dooley wasn’t real. He was a fictional character created by Dunne. His work included countless sketches and wide-ranging commentary, but he may be best known for his biting one-liner on newspapers, since reclaimed by journalists as central to the profession’s creed: “The job of the newspaper is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.”

The original quote is from Observations by Mr. Dooley, one of several works Dunne produced as the character, in which Dunne specifically satirizes the press’s penchant for trial-by-media. He presented Mr. Dooley through Irish dialect pieces, hence the diction, so the “affliction” quote below has been lightly edited for comprehension:

When anything was wrote about a man ’twas put this way: “We understand on good authority that … is on trial before Judge G. on an accusation of larceny. But we don’t think it’s true.” Nowadays, the larceny is discovered by a newspaper. The lead pipe is dug up your backyard by a reporter who knew it was there because he helped you bury it. A man knocks at your door early one mornin’ an’ you answer in your nighty. “In name of the law, I arrest you,” says the man seizin’ you by the throat. “Who are you?” you cry. “I’m a reporter for The Daily Slooth,” says he. “Photographer, do your duty!” You’re hauled off in the circulation wagon to the newspaper office where a confession is ready for you to sign; you’re tried by a jury of the staff, sentenced by the editor-in-chief, and at ten o’clock Friday the fatal thrap is sprung by the fatal thrapper of the family journal. The newspaper does evrything for us. It runs the police force and the banks, commands the militia, controls the legislature, baptizes the young, marries the foolish, comforts the afflicted, afflicts the comfortable, buries the dead and roasts them aftherward.

That journalists of all stripes have touted a scathing critique of their profession and repurposed it as a mission statement is a textbook definition of irony that belongs on a Roman pedestal behind bulletproof glass in the Smithsonian. What is most vexing about the modern interpretation of Dunne’s quote is that its new meaning is implied to be synonymous with dispassionately seeking truth, which it necessarily is not.

Robert Showah, “Journalism Is Not Activism”, Quillette, 2018-07-05.

February 6, 2020

Fallen flag – The Nickel Plate Road

Kevin J. Holland provides a brief look at the history of the New York, Chicago & St. Louis, better known as the “Nickel Plate Road”:

The New York, Chicago & St. Louis opened between Buffalo and Chicago on October 23, 1882, in many spots east of Cleveland just a stone’s throw from rival Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railway. What would become the Nickel Plate became a Vanderbilt property in January 1883.

Although eclipsed by the Lake Shore’s plush limiteds, NYC&StL from 1893 fielded three unpretentious, reliable Chicago to Buffalo, N.Y., passenger trains, establishing a long-standing pattern of modest passenger service. In 1897, Delaware, Lackawanna & Western entered the picture, conveying NYC&StL cars from Buffalo to Hoboken, N.J.

“The great … Nickel-plated railroad”

When NYC&StL was being surveyed, Editor F. R. Loomis of Ohio’s Norwalk Chronicle waxed enthusiastically on the railroad coming to town referring to it as “the great New York and St. Louis double-track, nickel-plated railroad.” Use of “Nickel Plate Road” proliferated, in newspapers and by the road itself.In 1914, LS&MS and Nickel Plate were wards of New York Central. Passage of the Clayton Act that same year was intended to bolster the earlier Sherman Antitrust Act, and left NYC with a dilemma. Enter brothers Oris P. and Mantis J. Van Sweringen, self-made Cleveland real-estate developers who purchased acreage from NYC Vice President Alfred H. Smith. “The Vans” as the brothers were known, approached Smith, by then NYC president, to discuss their plans involving land owned by the Nickel Plate. As the Clayton Act’s divestiture deadline loomed, Smith engineered a sale to the Vans of not only the land they sought, but of the entire Nickel Plate Road. Their Alleghany Corporation holding company eventually included control of the Nickel Plate, Chesapeake & Ohio, Pere Marquette, Erie, Wheeling & Lake Erie, Chicago & Eastern Illinois, and Missouri Pacific.

The gaunt NYC&StL was ripe for re-equipping under its new owners. Addressing the Vans’ lack of railroad experience, Smith orchestrated John J. Bernet’s move from an NYC vice-presidency to be Nickel Plate’s president. Neglected physical plant and obsolete motive power received needed attention under Bernet, who reincarnated the road into a lean and aggressive contender.