“Shady Maples“, a serving Canadian Army officer, explains why the skills and talents that allow an officer to rise to general rank in peacetime have no direct relationship with how that officer will perform in a shooting war:

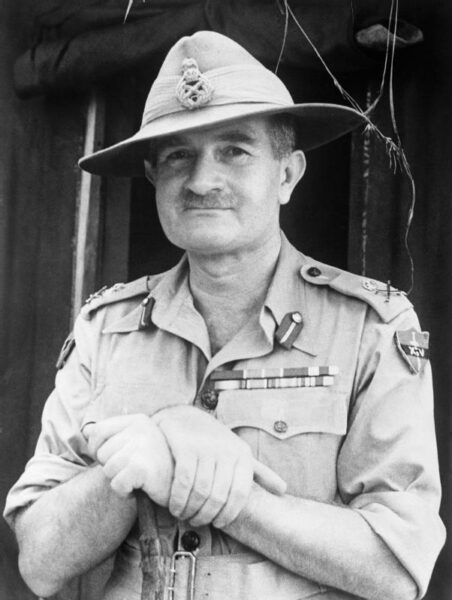

Field Marshal Sir William Slim (1891-1970), during his time as GOC XIVth Army in Burma.

Portrait by No. 9 Army Film & Photographic Unit via Wikimedia Commons.

I am not the first person to make these kinds of observations. Jim Storr has written about peacetime promotion culture in the British Army and Thomas E. Ricks did the same with U.S. Army. Here is an excerpt from Storr:

It appears that many of those whom the British Army promoted in peacetime during the twentieth century were found wanting on the outbreak of war. Promotion to high command in peacetime very much reflects the values of existing senior commanders, themselves largely the products of a peacetime promotion system. To that extent it reflects deeply held values, and has an obvious impact on operational effectiveness in war.

Roughly two-thirds of those who commanded formations in the BEF [British Expeditionary Force] of 1940 were either sacked, retired immediately, or were never given another formation to command in the field.

Ricks describes a similar phenomenon occurring in the U.S. Army during the Second World War. Many senior leaders who had risen during peacetime couldn’t perform under real-world conditions. Under the stern hand of George C. Marshall, then Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, generals were removed from command at a rate that is unheard of today. Many of those who were fired had glowing records and some went on to redeem their reputations in later commands, which suggests that they had been promoted too soon or too high above their level of competence.

More recently, Russia has been churning through general officers in Ukraine, seemingly desperate to find someone who can achieve Putin’s war aims. If an army systematically promotes its officers above their level of competence in peacetime, then clearly their selection and assessment criteria are not aligned with the actual job requirements.

To illustrate the point, Storr compares careers of Second World War British Field Marshals. The first, Field Marshal John Verreker a.k.a. Lord Gort, was Commander-in-Chief (C.-in-C.) of the BEF during its disastrous efforts in France in 1940.

[Gort] was the epitome of the system: young, highly decorated, charismatic, promoted through and entirely within the system. He was only 51 when appointed CIGS [Chief of Imperial General Staff] … As C.-in-C. of the BEF, he “fussed over details and things of comparatively little consequence” and had a “constant preoccupation with things of small detail”.

After he oversaw the evacuation of British troops from Dunkirk, Gort was removed from command and served out the rest of the war in non-combatant posts. It should be noted that Gort was not a bad soldier. During the First World War, he rose from the rank of captain to acting lieutenant-colonel and in the process earned the Distinguished Service Order (with bar) and the Victoria Cross. It was during the interwar years that Gort ascended from the substantive rank of Major to Field Marshal. Battles may be won with good-enough tactics and a lot of chutzpah, but Gort was unprepared for the complexities of wartime command at the strategic level. He did, however, excel at playing politics.

For contrast, here is Storr’s description of Field Marshal William “Bill” Slim:

[The] 47-year-old Bill Slim was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1938, perhaps at the last possible opportunity. Slim had not been to Sandhurst; he had gained his commission “through the back door” and had come from a modest background. The outbreak of the Second World War saw him commanding a brigade in East Africa. Within four years he was commanding the Fourteenth Army in Burma … Slim was obviously not the product of a stable heirarchy in peacetime. His rise to fame came entirely during wartime. He was arguably one of the greatest British generals of the twentieth century. The contrast with Gort could not be more marked.

For his part, Ricks has a takes a wider view of how the post-war U.S. Army made some officers too big to fail:

Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq were all small, ambiguous, increasingly unpopular wars, and in each, success was harder to define than it was in World War II. Firing generals seemed to send a signal to the public that the war was going poorly.

But that is only a partial explanation. Changes in our broader society are also to blame. During the 1950s, the military, like much of the nation, became more “corporate” — less tolerant of the maverick and more likely to favor conformist “organization men”. As a large, bureaucratized national-security establishment developed to wage the Cold War, the nation’s generals also began acting less like stewards of a profession, responsible to the public at large, and more like members of a guild, looking out primarily for their own interests.

It seems like loyalty up became more important than loyalty out.