The Tank Museum

Published 28 Oct 2022How much do you know about the Panhard EBR? Join David Willey for this week’s Tank Chat as he covers the development, design and use of this French armoured car.

(more…)

February 11, 2023

Tank Chats #167 | French Panhard EBR | The Tank Museum

QotD: “The rest of philosophy is not, as Alfred North Whitehead would have it, a series of footnotes to Plato … but all secular religions are”

Which is why I’m not going to humbug you about “the Classics.” Commanding you to “read the Classics!” would do you more harm than good at this point, because you have no idea how to read the Classics. Context is key, and nobody gets it anymore. Back when, that’s why they required Western Civ I — since all the Liberal Arts tie together, you needed to study the political and social history of Ancient Greece in order to read Plato (who in turn deepened your understanding of Greek society and politics … and our own, it goes without saying). I can’t even point you to a decent primer on Plato’s world, since all the textbooks since 1985 have been written by ax-grinding diversity hires.

And Plato’s actually pretty clear, as philosophers go. You’d really get into trouble with a muddled writer … or a much clearer one. A thinker like Nietzsche, for example, who’s such a lapidary stylist that you get lost in his prose, not realizing that he’s often saying the exact opposite of what he seems to be saying. To briefly mention the most famous example: “God is dead” isn’t the barbaric yawp of atheism triumphant. The rest of the paragraph is important, too, especially the next few words: “and we have killed him.” Nietzsche, supposedly the greatest nihilist, is raging against nihilism.

[…]

So here’s what I’d do, if I were designing a from-scratch college reading list. I’d go to the “for Dummies” versions, but only after clearly articulating the why of my reading list. I’d assign Plato, for example, as one of the earliest and best examples of one of mankind’s most pernicious traits: Utopianism. The rest of philosophy is not, as Alfred North Whitehead would have it, a series of footnotes to Plato … but all secular religions are. The most famous of these being Marxism, of course, and you’d get much further into the Marxist mindset by studying The Republic than you would by actually reading all 50-odd volumes of Marx. “What is Justice?” Plato famously asks in this work; the answer, as it turns out, is pretty much straight Stalinism.

How does he arrive at this extraordinary, counter-intuitive(-seeming) conclusion? The Cliff’s Notes will walk you through it. Check them out, then go back and read the real thing if the spirit moves you.

Articulating the “why” saves you all kinds of other headaches, too. Why should you read Hegel, for example? Because you can’t understand Marx without him … but trust me, if you can read The Republic for Dummies, you sure as hell don’t have to wade through Das Kapital. Marxism was a militantly proselytizing faith; they churned out umpteen thousand catechisms spelling it all out … and because they did, there are equally umpteen many anti-Marxist catechisms. Pick one; you’ll get all the Hegel you’ll ever need just from the context.

Severian, “How to Read ‘The Classics'”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-02-13.

February 10, 2023

When “Taffy 3” kicked the ass of the pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy

Chris Bray isn’t a milblogger, but I thought his summary of the Battle of Leyte Gulf was pretty darned good:

In October of 1944, US troops landing on Leyte Island in the Philippines were menaced from the sea by an enormous Japanese naval fleet that was divided into three separate attack forces.

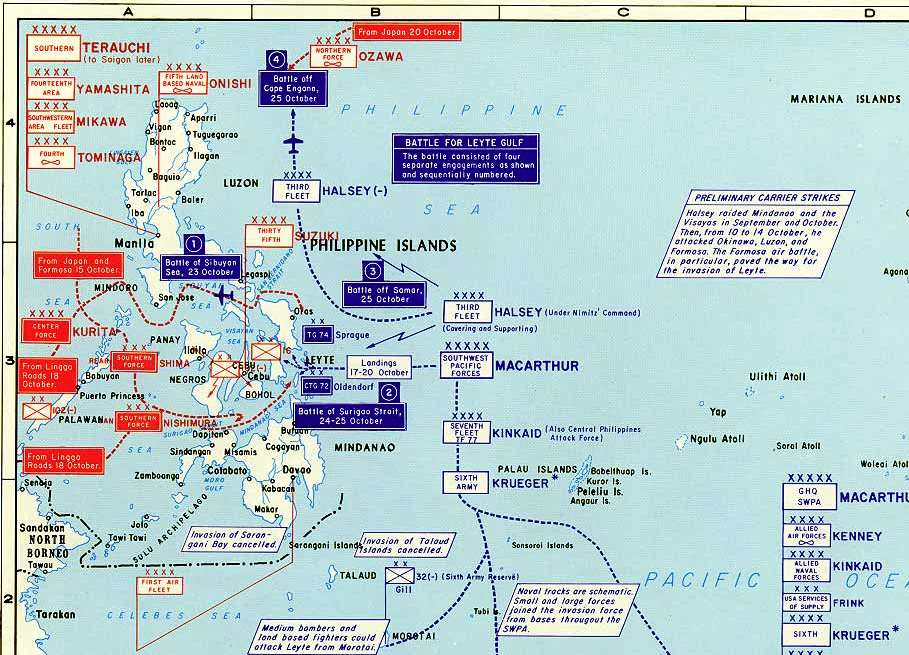

Detail of the West Point Military Atlas: World War II: Asia-Pacific Invasion of Leyte, October 1944 map.

https://www.westpoint.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/academics/academic_departments/history/WWII%20Asia/ww2%2520asia%2520map%252029.jpgSummarizing aggressively, the American ground forces were protected against an attack from the sea by the US Navy’s Third Fleet, commanded by Bull Halsey. But Halsey suddenly wasn’t there anymore, taking the bait of a decoy attack force [of de-planed Japanese carriers] and chasing it out into the sea. The Third Fleet’s departure uncovered Leyte Gulf, and the largest of the Japanese attack forces sailed in. Disaster became likely.

There were two American naval task forces in the path of the Japanese attack force, Taffy 2 and Taffy 3, but neither were meant for serious naval combat. They were supporting forces, designed to help the troops on the ground: a few escort carriers, a few lightly armed destroyer escorts, a very few destroyers. Aircraft on the American escort carriers were armed with 100-pound bombs to provide close air support to the infantry. The Japanese First Task Force had four battleships, eight cruisers, and eleven destroyers. One of the Japanese battleships was the Yamato, armed with 18-inch guns. The Japanese attack force sailed directly into contact with Taffy 3, which didn’t realize they were about to face the main Japanese attack force until they were already within range of its guns.

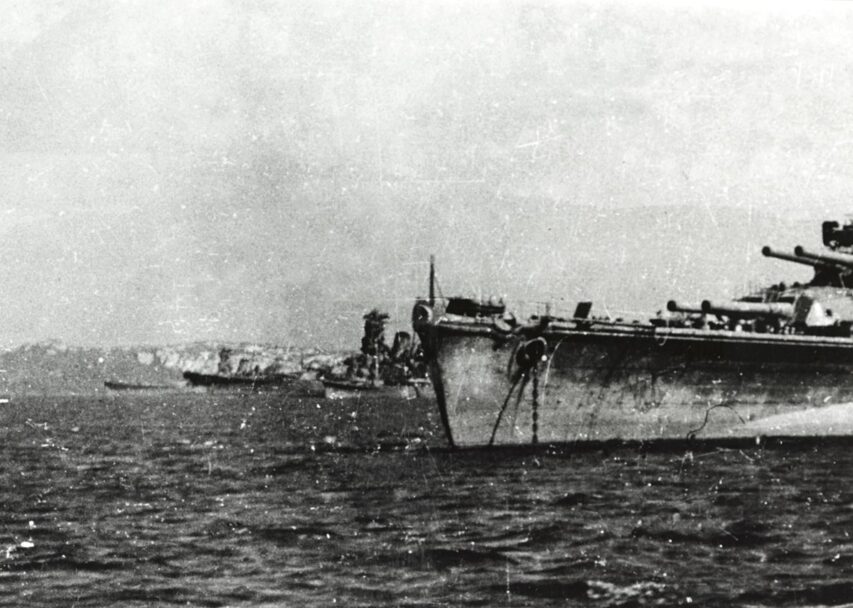

Imperial Japanese Navy ships at anchor in Brunei, Borneo shortly before the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Left to right, Musashi, Yamato, an unidentified cruiser, and Nagato.

Photo by Kazutoshi Hando from the US Naval History and Heritage Command collection.The commander of Taffy 3, Rear Admiral Clifton Sprague, saw immediately that his task force couldn’t survive the engagement, so he tried to salvage what he could: He ordered his destroyers and destroyer escorts to attack, to cover the hoped-for withdrawal of the escort carriers. The resulting battle is one of the best-known in naval history — and one of the least plausible, because Taffy 3 kicked the everloving shit out of that much larger Japanese attack force, compelling the Japanese to withdraw in the panicked belief that they’d sailed into the bulk of Halsey’s Third Fleet.

If you haven’t read [the late] James Hornfischer’s magnificent book about the battle, The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors, you should read it. The details are far beyond anything that could be summarized in a single short piece. But the battle was won by a remarkable combination of disciplined obedience, independent audacity, and a paradoxically disciplined disobedience — by men aggressively refusing to obey orders that threatened their cause.

The Fletcher-class destroyer USS Johnston (DD-557), sunk in the Battle off Samar, 25 October, 1944.

US Navy photo with enhancement work by Wild Surmise via Wikimedia Commons.The battle began with one of the US Navy’s most famous moments. Before Sprague had time to order anyone to do anything, the captain of the Johnston, one of Taffy 3’s few destroyers, turned to attack the Japanese fleet. We have confused and contradictory accounts of the orders given by Cmdr. Ernest Evans, because the man who gave them, and most of the men who heard them, died soon afterward, but he is supposed to have said something like this:

1.) We’re under the guns of a much larger Japanese fleet.

2.) Survival is not to be expected.

3.) Hard left rudder, all ahead flank.

We’re all going to die; attack. The Johnston sank, and Evans died, but his first torpedo run blew the bow off a Japanese cruiser — setting the tone of the fight.

Hitler’s Jazz Band – WW2 Documentary Special

World War Two

Published 9 Feb 2023Does Adolf Hitler like Duke Ellington? No, and nor do many National Socialists. But the story of the music in the Third Reich is more complicated than you might think. What if we told you that Joseph Goebbels has tried to create a Nazi-approved swing band tasked with bringing the Jazz War to the Allies?

(more…)

“What’s happening to children is morally and medically appalling”

In The Free Press, Jamie Reed explains why she gave up her job as as a case manager at The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital and is now speaking out against the early and aggressive therapeutic treatment of gender-confused children and teens:

Soon after my arrival at the Transgender Center, I was struck by the lack of formal protocols for treatment. The center’s physician co-directors were essentially the sole authority.

At first, the patient population was tipped toward what used to be the “traditional” instance of a child with gender dysphoria: a boy, often quite young, who wanted to present as — who wanted to be — a girl.

Until 2015 or so, a very small number of these boys comprised the population of pediatric gender dysphoria cases. Then, across the Western world, there began to be a dramatic increase in a new population: Teenage girls, many with no previous history of gender distress, suddenly declared they were transgender and demanded immediate treatment with testosterone.

I certainly saw this at the center. One of my jobs was to do intake for new patients and their families. When I started there were probably 10 such calls a month. When I left there were 50, and about 70 percent of the new patients were girls. Sometimes clusters of girls arrived from the same high school.

This concerned me, but didn’t feel I was in the position to sound some kind of alarm back then. There was a team of about eight of us, and only one other person brought up the kinds of questions I had. Anyone who raised doubts ran the risk of being called a transphobe.

The girls who came to us had many comorbidities: depression, anxiety, ADHD, eating disorders, obesity. Many were diagnosed with autism, or had autism-like symptoms. A report last year on a British pediatric transgender center found that about one-third of the patients referred there were on the autism spectrum.

Frequently, our patients declared they had disorders that no one believed they had. We had patients who said they had Tourette syndrome (but they didn’t); that they had tic disorders (but they didn’t); that they had multiple personalities (but they didn’t).

The doctors privately recognized these false self-diagnoses as a manifestation of social contagion. They even acknowledged that suicide has an element of social contagion. But when I said the clusters of girls streaming into our service looked as if their gender issues might be a manifestation of social contagion, the doctors said gender identity reflected something innate.

To begin transitioning, the girls needed a letter of support from a therapist — usually one we recommended — who they had to see only once or twice for the green light. To make it more efficient for the therapists, we offered them a template for how to write a letter in support of transition. The next stop was a single visit to the endocrinologist for a testosterone prescription.

That’s all it took.

When a female takes testosterone, the profound and permanent effects of the hormone can be seen in a matter of months. Voices drop, beards sprout, body fat is redistributed. Sexual interest explodes, aggression increases, and mood can be unpredictable. Our patients were told about some side effects, including sterility. But after working at the center, I came to believe that teenagers are simply not capable of fully grasping what it means to make the decision to become infertile while still a minor.

Water-Cooled .50s: The US Navy Mk22 Pedestal Mount

Forgotten Weapons

Published 27 Oct 2022In 1942, the US Navy adopted the Mk22 Pedestal mount, which fitted a pair of water-cooled Browning M2 machine guns (one left-hand feed and one right-hand). It was used for antiaircraft use primarily, and was also adopted by the Army as the M46 in 1943. The mount was an update to the previous single-gun MK21.

The gunner was protected by a 3/8″ (9.5mm) hardened steel shield, and the mount could rotate a full 360 degrees, with elevation from -10 degrees to 80 degrees. They were produced by the Heintz Manufacturing company (no relation to the Heinz company that makes ketchup) of Pittsburgh from 1942 until 1945.

(more…)

QotD: Before Star Wars or the MCU there was … the Arthurian Narrative Universe

I’m referring to the obsession with knights and their adventures — and especially those linked to King Arthur and his Round Table. These were the most popular stories in Europe for hundreds of years. Readers couldn’t get enough of them, and even as the stories got stale and predictable, the audience demanded more and more.

The situation is almost exactly the same as the Marvel Cinematic Universe. We have a major character named King Arthur, but he was linked to numerous spinoffs and sequels. The other heroes connected to him soon established their own brands — including Lancelot, Merlin, Gawain, Tristan, Percival, and many others. Readers who enjoyed one of the heroes, often became fans of others.

If you make a list, the Arthurian Narrative Universe (ANU) has more than fifty protagonists. Not all of them became major brands, but that’s no different from the movie business, where even Disney can’t keep every superhero on the payroll.

Even more to the point, these stories were business initiatives, expected to enrich their owners. It’s hardly a coincidence that the most influential collection of stories about King Arthur in English, Le Morte d’Arthur published in 1485, originated as a profit-making venture by the earliest commercial publisher in Britain.

William Caxton was not only the first person to set up a printing press in England, but also the first retailer of printed books in the country. He acquired the manuscript of Le Morte d’Arthur from Thomas Malory, the Stan Lee of his day, and turned it into the single most influential secular British book between the time of Chaucer and the rise of Shakespeare.

He didn’t do it because he loved English history. (The painful truth is that very little — in fact next to nothing — in the Arthurian tales comes from documented historical events.) He didn’t even publish the book because he loved a good story. Caxton wanted to make a buck — or a pound sterling, I ought to say. He had identified the right brand franchise, much like the Walt Disney Company in the current day, and would milk it for all it was worth.

But here’s the most amazing thing about his brand franchise: Arthurian stories had been circulating in manuscript for more than 300 years at this point. And many of the details in these narratives are much older than that, reaching back to accounts of knights who fought in the Crusades, if not earlier.

We can trace the story of Lancelot and his adulterous romance with Queen Guinevere at least back to 1180. The story of the knights’ quest for the Holy Grail dates at least back to 1190. The first mention of King Arthur is no later than 828 AD.

Stop and consider the implications. King Arthur was the most popular brand franchise in secular narratives when he was 650 years old!

Of course, it was absurd. Nobody undertook knightly adventures of this sort during the Renaissance, but storytellers pretended otherwise. Everything about these narratives was outdated, unrealistic, and repetitive — the people who read these tales didn’t own suits of armor or compete in jousting tournaments. Those things had disappeared from society. But the audience still wanted these stories, so the same plots and characters got recycled again and again.

Ted Gioia, “Don Quixote Tells Us How the Star Wars Franchise Ends”, The Honest Broker, 2022-11-09.

February 9, 2023

“Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future” … but sometimes it’s almost prophetic

Once again, Ted Gioia’s Honest Broker Substack has something interesting I’d like to share with you (I wouldn’t blame you at all for cutting out the middleman and just subscribing for yourself):

Today I want to focus on a single paragraph published in 1960.

You’re asking yourself: How much can a single paragraph matter — especially if it was written 63 years ago? But read it first and judge for yourself.

It’s a chilling paragraph.

[…]

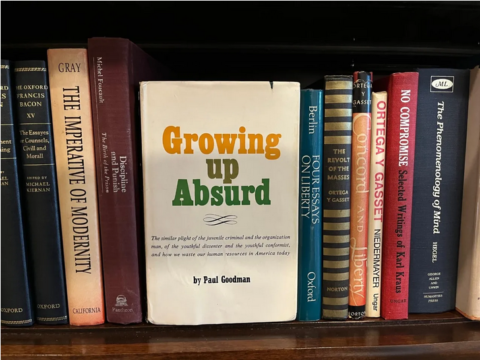

By any measure, [Paul Goodman] was one of the most eccentric thinkers of the era. Yet he anticipated our current situation with more insight than any of his peers.

Let’s look at this one paragraph from the Preface to Growing Up Absurd. It’s a long paragraph — it takes up most of two pages. So we will break it down into pieces.

Goodman begins with a puzzle he needs to solve — society is stagnating everywhere, and we all can see it. But there’s no action plan to fix it. There’s a lot of huffing and puffing and finger-pointing everywhere, but nobody has even started on developing a practical agenda.

According to Goodman, this is because people “have ceased to be able to imagine alternatives”. Everybody accepts that the current system “is the only possibility of society, for nothing else is thinkable”.

Now comes his analysis, and — to my surprise — Goodman begins by talking about music. This was the last thing I expected in a social critique, but for Goodman the manufacturing of hit songs is a metaphor for everything else that’s wrong in a stagnant society.

He writes:

Let me give a couple of examples of how this [inability to imagine healthy alternatives] works. Suppose (as is the case) that a group of radio and TV broadcasters, competing in the Pickwickian fashion of semi-monopolies, control all the stations and channels in an area, amassing the capital and variously bribing Communications Commissioners in order to get them; and the broadcasters tailor their programs to meet the requirements of their advertisers of the censorship, of their own slick and clique tastes, and of a broad common denominator of the audience, none of whom may be offended: they will then claim not only that the public wants the drivel that they give them, but indeed that nothing else is being created. Of course it is not! Not for these media; why should a serious artist bother?

When I first read this, I was dumbstruck. Goodman wrote this during the winter of 1959 and 1960, when radio stations were independent and freewheeling. Back in my teen years, a single business was only allowed to control one AM station and one FM station. In 1985 this was increased to 12 stations on each band. And in 1994 this was raised again, this time to 20 AM stations and 20 FM stations.

But then all hell broke lose when the Telecommunications Act of 1996 passed in the Senate by a 91 to 5 margin and was signed into law. Now the sky was the limit — and all the airwaves it contained.

Soon Clear Channel Communications owned more than 1,200 radio stations in some 300 cities. The company began the process of standardizing and homogenizing our musical culture. We still suffer from that today.

Even after radio started losing influence in the Internet Age, huge streaming platforms (Spotify, Apple Music, etc.) ensured that access to the ears of America would be controlled by a tiny number of huge corporations. A musical culture that was once local, indie, and flexible has become centralized, corporatized, and stagnant.

How could Paul Goodman even dream of such a scenario back in 1960? That future was decades away at the time.

But we are only at the start of this visionary paragraph. Goodman now explains that the same thing will happen in universities.

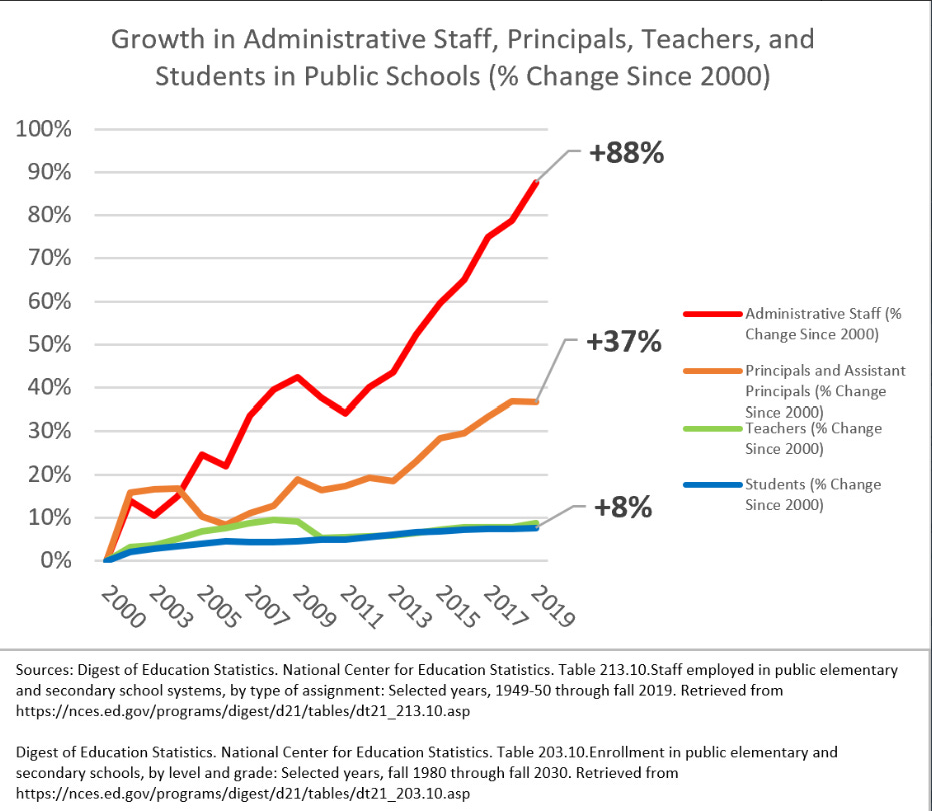

Colleges and schools were small and non-bureaucratic back in 1960. Yet Goodman sees a crisis looming. On the next page Goodman warns against “the topsy-turvy situation that a teacher must devote himself to satisfying the administrator and financier rather than to doing his job, and a universally admired teacher is fired for disobeying an administrative order that would hinder teaching”.

Administration at US colleges has grown exponentially in the last two decades and has turned almost every academic institution into a plodding bureaucracy — but how in the world did Goodman anticipate this in 1960?

Now let’s return to our chilling paragraph. Immediately after discussing radio stations, Goodman adds a gargantuan sentence. It jumps all over the place but hits the target at every twist and turn:

Or suppose again (as is not quite the case) that in a group of universities only faculties are chosen that are “safe” to the businessmen trustees or the politically appointed regents, and these faculties give out all the degrees and licenses and union cards to the new generation of students, and only such universities can get Foundation or government money for research, and research is incestuously staffed by the same sponsors and according to the same policy, and they allow no one but those they choose, to have access to either the classroom or expensive apparatus: it will then be claimed that there is no other learning or professional competence; that an inspired teacher is not “solid”; that the official projects are the direction of science; that progressive education is a failure; and finally, indeed — as in Dr. James Conant’s report on the high schools — that only 15 per cent of the youth are “academically talented” enough to be taught hard subjects.

Here in a nutshell is the credentialing crisis of our times. Learning is replaced by exclusionary certification programs that limit career opportunities — unless you take out loans and “purchase” the necessary credential from these academic gatekeepers.

This has become so destructive in our own time that many are crushed by student loans, and others seek ingenious ways of bypassing college entirely. There’s no way that Goodman could have grasped this in 1960 — when only 7.7 percent of Americans had college degrees.

Nor could he have known about the replicability crisis in science or the destructive games now played in awarding of scientific grants. Those are the problems of our times — not his.

But somehow Paul Goodman saw it coming.

Get flat boards EVERY TIME with this simple process // Handtool stock-prep

Rex Krueger

Published 8 Feb 2023Flattening by hand can be intimidating, unless you have a process.

(more…)

On Clausewitz

Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook Substack has covered a lot of WW1-era artillery unit organization since I started subscribing, but on Tuesday he offered some notes on how to approach the life and work of Carl von Clausewitz for the non-professional-soldier audience:

The beginning of wisdom where Clausewitz is concerned is to realize that he was the professional soldier with a great deal of trigger time under his belt. If you doubt this, crack open one of the two fine biographies that are readily available to English-speaking readers. Indeed, even if you need no convincing on the subject of the active service of the Philosopher of War, a biography is a good place to start your engagement with this extraordinarily interesting man.

For reasons of style and sentiment, I prefer the older of the two biographies. Composed by popular historian Roger Parkinson in the days before Clausewitz was cool, Clausewitz: A Biography devotes nine of its seventeen substantive chapters (the three-page epilogue doesn’t count) to tales of active service. It is, moreover, the sort of book that was written to be read, for edification and enjoyment, by intelligent members of the general public.

Clausewitz: His Life and Work, is the product of our own times, one in which a great deal of military history is written by people with doctoral degrees, and people with doctoral degrees teach at war colleges. Though afflicted with both of these aforementioned handicaps, author Donald J. Stoker has managed to produce a work as readable as that of Parkinson. Better yet, he has succeeded in devoting even more attention to periods when Clausewitz was more concerned with the immediate possibility of enfilade and defilade than the distinction between “nature” and “character”.

Once you have learned a bit about Clausewitz the soldier, you will be ready to embrace Carl the lover. For this stage of your journey, you will have but one companion, Vanya Eftimova Bellinger’s Marie von Clausewitz: The Woman Behind the Making of On War.

Fear not, while this biography of the remarkable Frau von Clausewitz is a love story, it has little in common with what passes for romance these days. Neither is it, as the subtitle suggests, largely about the posthumous assembly of the various fragments of On War into the work that made its author famous. (Professor Bellinger tells that tale in less than five pages.) Rather, Marie von Clausewitz is largely a tale of the books, ideas, culture, and politics of the times and places in which the heroine and her husband lived.

If you wish to delve further into the aforementioned milieu, you should read all three of the books of Peter Paret that have “Clausewitz” in their titles. In sharp contrast to his partner in translation, Professor Paret was much more interested in the ideas that influenced Clausewitz than the way that people of subsequent generations reacted to the products of his pen. (While the greatest, by far, of all American Clausewitz scholars, Paret was, first and last, a student of the great reform movement that took place in Prussia after the disaster of Jena-Auerstadt.) If, however, you wish a more direct route into the military mind of the subject of this piece, then the next step in your journey should consist of a long visit with Gerhard von Scharnhorst.

Attractive VTOL autogyro with unrealised potential; the story of the Avian 2/180 Gyroplane

Polyus

Published 10 Jan 2019The Avian 2/180 Gyroplane was a project that rose from the ashes of the Avro Arrow cancellation. Five former employee formed their own company and set out to build a new kind of autogyro. Their Gyroplane could take off and land vertically and could fly at speeds up to 265 km/h. Although it never made any sales, it is an impressive project that deserves some attention.

(Also sorry for the flickering in the video. I did my best to limit it but the source video didn’t give me much to work with.)

(more…)

QotD: Collecting taxes, Medieval-style

I want to begin with an observation, obvious but frequently ignored: states are complex things. The apparatus by which a state gathers revenue, raises armies (with that revenue), administers justice and tries to organize society – that apparatus requires people. Not just any people: they need to be people of the educated, literate sort to be able to record taxes, read the laws and transmit (written) royal orders and decrees.

(Note: for a more detailed primer on what this kind of apparatus can look like, check out Wayne Lee’s (@MilHist_Lee) talk “Reaping the Rewards: How the Governor, the Priest, the Taxman, and the Garrison Secure Victory in World History” here. He’s got some specific points he’s driving at, but the first half of the talk is a broad overview of the problems you face as a suddenly successful king. Also, the whole thing is fascinating.)

In a pre-modern society, this task – assembling and organizing the literate bureaucrats you need to run a state – is very difficult. Literacy is often very low, so the number of individuals with the necessary skills is minuscule. Training new literate bureaucrats is expensive, as is paying the ones you have, creating a catch-22 where the king has no money because he has no tax collectors and he has no tax collectors because he has no money. Looking at how states form is thus often a question of looking at how this low-administration equilibrium is broken. The administrators you need might be found in civic elites who are persuaded to do the job in exchange for power, or in a co-opted religious hierarchy of educated priests, for instance.

Vassalage represents another response to the problem, which is the attempt to – as much as possible – do without. Let’s specify terms: I am using “vassalage” here because it is specific in a way that the more commonly used “feudalism” is not. I am not (yet) referring to how peasants (in Westeros the “smallfolk”) interact with lords (which is better termed “manorialism” than as part of feudalism anyway), but rather how military aristocrats (knights, lords, etc) interact with each other.

So let us say you are a king who has suddenly come into a lot of land, probably by bloody conquest. You need to extract revenue from that land in order to pay for the armies you used to conquer it, but you don’t have a pile of literate bureaucrats to collect those taxes and no easy way to get some. By handing out that land to your military retainers as fiefs (they become your vassals), you can solve a bunch of problems at once. First, you pay off your military retainers for their service with something you have that is valuable (land). Second, by extracting certain promises (called “homage”) from them, you ensure that they will continue to fight for you. And third, you are partitioning your land into smaller and smaller chunks until you get them in chunks small enough to be administered directly, with only a very, very minimal bureaucratic apparatus. Your new vassals, of course, may do the same with their new land, further fragmenting the political system.

This is the system in Westeros, albeit after generations of inheritance (such that families, rather than individuals, serve as the chief political unit). The Westerosi term for a vassal is a “bannerman”. Greater military aristocrats with larger holding are lords, while lesser ones are landed knights. Landed knights often hold significant lands and a keep (fortified manner house), which would make them something more akin to European castellans or barons than, say, a 14th century English Knight Banneret (who is unlikely to have been given permission to fortify his home, known as a license to crenellate). What is missing from this system are the vast majority of knights, who would not have had any kind of fortified dwelling or castle, but would have instead been maintained as part of the household of some more senior member of the aristocracy. A handful of landless knights show up in Game of Thrones, but they should be by far the majority and make up most of the armies.

There’s one final missing ingredient here, which is castles, something Westeros has in abundance. Castles – in the absence of castle-breaking cannon – shift power downward in this system, because they allow vassals to effectively resist their lieges. That may not manifest in open rebellion so much as a refusal to go on campaign or supply troops. This is important, because it makes lieges as dependent on their vassals as vassals are on their lieges.

Bret Devereaux, “New Acquisitions: How It Wasn’t: Game of Thrones and the Middle Ages, Part III”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-06-12.

February 8, 2023

The King of Siam’s Massaman Curry

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 7 Feb 2023

(more…)

The ghastly Thirty Years’ War in Europe

In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams outlines the state of Europe four hundred years ago:

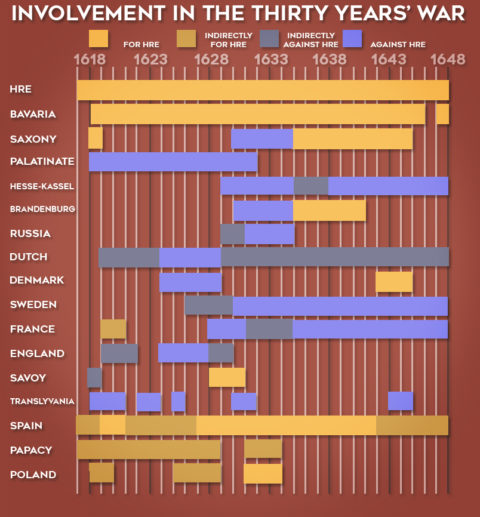

A war as long and as complex requires something like this to help keep the narrative somewhat understandable.

Exactly four hundred years ago, a dark shadow was slithering across mainland Europe. It stretched its bleak, cold presence into each hearth and home. Everything it touched turned to ruin. Musket and rapier, smoke and fire, ruled supreme. Nothing was immune. Animals and children starved to death, mothers and adolescent girls were abused and tortured. The lucky ones died, alongside their brothers and fathers, slain in battle. Possessions were looted, crops destroyed, barns and houses burned. There seemed no end to the evil and pestilence. Sixteen generations ago, many believed the end of the world had arrived.

This was not a tale of Middle Earth. The place was central Europe in the early 17th century. In 1618 the future Holy Roman emperor Ferdinand II, a zealous follower of the Jesuits, had attempted to restore the Catholic Church as the only religion in the Empire and exterminate any form of religious dissent. Protestant nobles in Bohemia and Austria rose up in rebellion. The conflict soon widened, fuelled by the political ambitions of adjacent powers. In Europe’s heartland, three denominations fought it out: Roman Catholicism, Lutheranism and Calvinism.

The result was an interwoven tangle of diplomatic plot twists, temporary alliances and coalitions, as princes, bishops and potentates beseeched outside powers to help. The struggle, which lasted for thirty years, boiled down to the Roman Catholic and Habsburg-led Holy Roman Empire, fighting an incongruous array of Protestant towns and statelets, aided by the anti-Catholic powers of Sweden under Gustavus Adolphus, and the United Netherlands. France and Spain also took advantage of the distractions of war to indulge in their own sub-campaigns. Britain took no formal part but was about to become embroiled in her own civil war.

The principal battleground for this collective contest of arms centred on the towns and principalities of what would become Germany, northern Italy, the Netherlands and the Czech Republic. The war devastated many regions on a scale unseen again until 1944–45. For example, at Magdeburg on the River Elbe, 20,000 of 25,000 inhabitants died, with 1,700 of its 1,900 buildings ruined. In Czech Bohemia, 40 per cent of the population perished, with 100 towns and more than a thousand villages laid waste. At Nordlingen in 1634, around 16,000 soldiers were killed in a single day’s battle. The town took three centuries for its population to return to pre-war levels. Refugees from smaller settlements swelled the many walled cities, increasing hunger and spreading disease.

Too diminutive to defend themselves, all states hired mercenaries, of whom a huge number flourished in the era, enticed by the prospect of quick wealth in exchange for proficiency with sword and musket. Employed by every antagonist, but beholden to no one, these armed brigands — regiments would be too grand a term for the uniformed thugs they were — roamed at will. With their pikes and their muskets, they plundered the countryside in search of booty, food and transport. In their wake, they left burning towns, ruined villages, pillaged farms. Lead was stripped from houses and church roofs for ammunition.

Left to right:

The Defenestration of Prague (23 May, 1618), The death of Gustavus Adolphus at Lützen (16 November, 1632), Dutch warships prior to the Battle of the Downs (21 October, 1639), and The Battle of Rocroi (19 May, 1643).

Collage by David Dijkgraaf via Wikimedia Commons.When in the winter of 1634 Swedish mercenaries were refused food and wine by the inhabitants of Linden, a tiny Bavarian settlement, they raped and looted their way through the village, leaving it uninhabitable. Across Europe, travellers noted the human and animal carcasses that decorated the meadows, streams polluted by the dead and rotting crops, presided over only by ravens and wolves. No respect was shown for the lifeless. Survivors stripped corpses of clothing and valuables; if lucky, the deceased were tossed into unmarked mass graves, since lost to history.

Having triggered the war, Ferdinand predeceased its end. We can never know how many died in Europe’s last major conflagration triggered by religion. Archives perished in the flames, and survivors were not interested in computations. Historians now put the death toll at between 8 and 12 million. Probably 500,000 perished in battle, with the rest, mostly civilians, expiring through starvation and disease. We think these casualties may equate to as much as 20 per cent of mainland Europe’s population and perhaps one-third of those in modern Germany, bringing the Thirty Years’ War a potency similar to the Black Death or either world war. The region did not recover for at least three generations.

Economic activity, land use and ownership altered terminally. When the exhausted powers finally met in October 1648 at Osnabrück and Münster in the German province of Westphalia to end the directionless slaughter, of whom self-serving militias were the only beneficiaries, Europe’s balance of power had shifted tectonically. Fresh rules of conflict and the legitimacy of a new network of 300 sovereign states, independent from a Holy Roman Emperor or a Pope, marked the struggle as a watershed moment, leading to the Enlightenment and an era that disappeared only with Napoleon.