No one questions that the formative period for Gandhi as a political leader was his time in South Africa. Throughout history Indians, divided into 1,500 language and dialect groups (India today has 15 official languages), had little sense of themselves as a nation. Muslim Indians and Hindu Indians felt about as close as Christians and Moors during their 700 years of cohabitation in Spain. In addition to which, the Hindus were divided into thousands of castes and sub-castes, and there were also Parsees, Sikhs, Jains. But in South Africa officials had thrown them all in together, and in the mind of Gandhi (another one of those examples of nationalism being born in exile) grew the idea of India as a nation, and Muslim-Hindu friendship became one of the few positions on which he never really reversed himself. So Gandhi — ignoring Arabs and Turks — became an adamant supporter of the Khilafat [Caliphate] movement out of strident Indian nationalism. He had become a national figure in India for having unified 13,000 Indians of all faiths in South Africa, and now he was determined to reach new heights by unifying hundreds of millions of Indians of all faiths in India itself. But this nationalism did not please everyone, particularly Tolstoy, who in his last years carried on a curious correspondence with the new Indian leader. For Tolstoy, Gandhi’s Indian nationalism “spoils everything.”

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.

November 27, 2018

QotD: Gandhi’s view of India as a nation

November 7, 2018

QotD: Gandhi and the fall of the Caliphate

… it should not be thought for one second that Gandhi’s finally full-blown desire to detach India from the British empire gave him the slightest sympathy with other colonial peoples pursuing similar objectives. Throughout his entire life Gandhi displayed the most spectacular inability to understand or even really take in people unlike himself — a trait which V.S. Naipaul considers specifically Hindu, and I am inclined to agree. Just as Gandhi had been totally unconcerned with the situation of South Africa’s blacks (he hardly noticed they were there until they rebelled), so now he was totally unconcerned with other Asians or Africans. In fact, he was adamantly opposed to certain Arab movements within the Ottoman empire for reasons of internal Indian politics.

At the close of World War I, the Muslims of India were deeply absorbed in what they called the “Khilafat” movement — “Khilafat” being their corruption of “Caliphate,” the Caliph in question being the Ottoman Sultan. In addition to his temporal powers, the Sultan of the Ottoman empire held the spiritual position of Caliph, supreme leader of the world’s Muslims and successor to the Prophet Muhammad. At the defeat of the Central Powers (Germany, Austria, Turkey), the Sultan was a prisoner in his palace in Constantinople, shorn of his religious as well as his political authority, and the Muslims of India were incensed. It so happened that the former subject peoples of the Ottoman empire, principally Arabs, were perfectly happy to be rid of this Caliph, and even the Turks were glad to be rid of him, but this made no impression at all on the Muslims of India, for whom the issue was essentially a club with which to beat the British. Until this odd historical moment, Indian Muslims had felt little real allegiance to the Ottoman Sultan either, but now that he had fallen, the British had done it! The British had taken away their Khilafat! And one of the most ardent supporters of this Indian Muslim movement was the new Hindu leader, Gandhi.

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.

October 15, 2018

German Afghanistan Mission I OUT OF THE ETHER

The Great War

Published on 13 Oct 2018Thank you again Jack Sharpe!

October 4, 2018

QotD: Gandhi in World War One

We are therefore presented with the seeming anomaly of a Gandhi who, in Britain when war broke out in August 1914, instantly contacted the War Office, swore that he would stand by England in its hour of need, and created the Indian Volunteer Corps, which he might have commanded if he hadn’t fallen ill with pleurisy. In 1915, back in India, he made a memorable speech in Madras in which he proclaimed, “I discovered that the British empire had certain ideals with which I have fallen in love …” In early 1918, as the war in Europe entered its final crisis, he wrote to the Viceroy of India, “I have an idea that if I become your recruiting agent-in-chief, I might rain men upon you,” and he proclaimed in a speech in Kheda that the British “love justice; they have shielded men against oppression.” Again, he wrote to the Viceroy, “I would make India offer all her able-bodied sons as a sacrifice to the empire at this critical moment …” To some of his pacifist friends, who were horrified, Gandhi replied by appealing to the Bhagavad Gita and to the endless wars recounted in the Hindu epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, adding further to the pacifists’ horror by declaring that Indians “have always been warlike, and the finest hymn composed by Tulsidas in praise of Rama gives the first place to his ability to strike down the enemy.”

This was in contradiction to the interpretation of sacred Hindu scriptures Gandhi had offered on earlier occasions (and would offer later), which was that they did not recount military struggles but spiritual struggles; but, unusual for him, he strove to find some kind of synthesis. “I do not say, ‘Let us go and kill the Germans,’” Gandhi explained. “I say, ‘Let us go and die for the sake of India and the empire.’” And yet within two years, the time having come for swaraj (home rule), Gandhi’s inner voice spoke again, and, the leader having found his cause, Gandhi proclaimed resoundingly: “The British empire today represents Satanism, and they who love God can afford to have no love for Satan.”

The idea of swaraj, originated by others, crept into Gandhi’s mind gradually. With a fair amount of winding about, Gandhi, roughly, passed through three phases. First, he was entirely pro-British, and merely wanted for Indians the rights of Englishmen (as he understood them). Second, he was still pro-British, but with the belief that, having proved their loyalty to the empire, Indians would be granted some degree of swaraj. Third, as the home-rule movement gathered momentum, it was the swaraj, the whole swaraj, and nothing but the swaraj, and he turned relentlessly against the crown. The movie to the contrary, he caused the British no end of trouble in their struggles during World War II.

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.

September 27, 2018

QotD: Gandhi’s views on Britain

… as almost always with historical films, even those more honest than Gandhi, the historical personage on which the movie is based is not only more complex but more interesting than the character shown on the screen. During his entire South African period, and for some time after, until he was about fifty, Gandhi was nothing more or less than an imperial loyalist, claiming for Indians the rights of Englishmen but unshakably loyal to the crown. He supported the empire ardently in no fewer than three wars: the Boer War, the “Kaffir War,” and, with the most extreme zeal, World War I. If Gandhi’s mind were of the modern European sort, this would seem to suggest that his later attitude toward Britain was the product of unrequited love: he had wanted to be an Englishman; Britain had rejected him and his people; very well then, they would have their own country. But this would imply a point of “agonizing reappraisal,” a moment when Gandhi’s most fundamental political beliefs were reexamined and, after the most bitter soul-searching, repudiated. But I have studied the literature and cannot find this moment of bitter soul-searching. Instead, listening to his “inner voice” (which in the case of divines of all countries often speaks in the tones of holy opportunism), Gandhi simply, tranquilly, without announcing any sharp break, set off in a new direction.

It should be understood that it is unlikely Gandhi ever truly conceived of “becoming” an Englishman, first, because he was a Hindu to the marrow of his bones, and also, perhaps, because his democratic instincts were really quite weak. He was a man of the most extreme, autocratic temperament, tyrannical, unyielding even regarding things he knew nothing about, totally intolerant of all opinions but his own. He was, furthermore, in the highest degree reactionary, permitting in India no change in the relationship between the feudal lord and his peasants or servants, the rich and the poor. In his The Life and Death of Mahatma Gandhi, the best and least hagiographic of the full-length studies, Robert Payne, although admiring Gandhi greatly, explains Gandhi’s “new direction” on his return to India from South Africa as follows:

He spoke in generalities, but he was searching for a single cause, a single hard-edged task to which he would devote the remaining years of his life. He wanted to repeat his triumph in South Africa on Indian soil. He dreamed of assembling a small army of dedicated men around him, issuing stern commands and leading them to some almost unobtainable goal.

Gandhi, in short, was a leader looking for a cause. He found it, of course, in home rule for India and, ultimately, in independence.

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.

September 12, 2018

QotD: Origins of India’s caste system

In India, the notion of Hindu culture as a giant conspiracy by Aryan invaders to enshrine their descendants at the top of the social order for the rest of eternity perhaps struck a little too close to home.

But Reich’s laboratory has found that the old Robert E. Howard version is actually pretty much what happened. Conan the Barbarian-like warriors with their horse-drawn wagons came charging off the Eurasian steppe and overran much of Europe and India. Reich laments:

The genetic data have provided what might seem like uncomfortable support for some of these ideas — suggesting that a single, genetically coherent group was responsible for spreading many Indo-European languages.

Much more acceptable to Indian intellectuals than the idea that ancient conquerors from the Russian or Kazakhstani steppe took over the upper reaches of Indian culture has been the theory of Nicholas B. Dirks, the Franz Boas Professor of History and Anthropology at Columbia, that the British malignantly transformed diverse local Indian customs into the suffocating system of caste that we know today.

Now, though, Reich’s genetic evidence shows that caste has controlled who married whom in India for thousands of years:

Rather than inventions of colonialism as Dirks suggested, long-term endogamy as embodied in India today in the institution of caste has been overwhelmingly important for millennia.

This is in harmony with economic historian Gregory Clark’s recent discovery in his book of surname analysis, The Son Also Rises (Clark loves Hemingway puns), that economic mobility across the generations is not only lower than expected in most of the world, but it is virtually nonexistent in India.

Steve Sailer, “Reich’s Laboratory”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-03-28.

August 31, 2018

How did Britain Conquer India? | Animated History

The Armchair Historian

Published on 10 Aug 2018Check out History With Hilbert: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hs1sw…

Our Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/armchairhistory

Our Twitter: https://twitter.com/ArmchairHist

Sources:

https://dailyhistory.org/Why_was_Brit…

1857 Indian War of Independence: 1857 Indian Sepoys’ Mutiny, Shahid Hussain Raja

The East India Company, Brian Gardner

The Corporation that Changed the World: How the East India Company Shaped the Modern Multinational, Nick Robins

A History of India, Peter Robb

August 29, 2018

Out of Context: How to Make Bad History Worse | World War 2

Knowing Better

Published on 5 Mar 2018Churchill was a genocidal maniac. The Japanese were rounded up into concentration camps. FDR let Pearl Harbor happen. When you take history out of context, you can make it say whatever you want – including making bad things worse.

A long list of links to sources is included, but I’m too lazy to re-link ’em all, just go to YouTube to see them. Back in 2009, I did a short fisking of Pat Buchanan’s hit-piece on Churchill’s “reponsibility” for the outbreak of WW2.

August 25, 2018

QotD: India’s caste system

… Gandhi, born the son of the Prime Minister of a tiny Indian principality and received as an attorney at the bar of the Middle Temple in London, [began] his climb to greatness as a member of the small Indian community in, precisely, South Africa. Natal, then a separate colony, wanted to limit Indian immigration and, as part of the government program, ordered Indians to carry identity papers (an action not without similarities to measures under consideration in the U.S. today to control illegal immigration). The film’s lengthy opening sequences are devoted to Gandhi’s leadership in the fight against Indians carrying their identity papers (burning their registration cards), with for good measure Gandhi being expelled from the first-class section of a railway train, and Gandhi being asked by whites to step off the sidewalk. This inspired young Indian leader calls, in the film, for interracial harmony, for people to “live together.”

Now the time is 1893, and Gandhi is a “caste” Hindu, and from one of the higher castes. Although, later, he was to call for improving the lot of India’s Untouchables [Dalits], he was not to have any serious misgivings about the fundamentals of the caste system for about another thirty years, and even then his doubts, to my way of thinking, were rather minor. In the India in which Gandhi grew up, and had only recently left, some castes could enter the courtyards of certain Hindu temples, while others could not. Some castes were forbidden to use the village well. Others were compelled to live outside the village, still others to leave the road at the approach of a person of higher caste and perpetually to call out, giving warning, so that no one would be polluted by their proximity. The endless intricacies of Hindu caste by-laws varied somewhat region by region, but in Madras, where most South African Indians were from, while a Nayar could pollute a man of higher caste only by touching him, Kammalans polluted at a distance of 24 feet, toddy drawers at 36 feet, Pulayans and Cherumans at 48 feet, and beef-eating Paraiyans at 64 feet. All castes and the thousands of sub-castes were forbidden, needless to say, to marry, eat, or engage in social activity with any but members of their own group. In Gandhi’s native Gujarat a caste Hindu who had been polluted by touch had to perform extensive ritual ablutions or purify himself by drinking a holy beverage composed of milk, whey, and (what else?) cow dung.

Low-caste Hindus, in short, suffered humiliations in their native India compared to which the carrying of identity cards in South Africa was almost trivial. In fact, Gandhi, to his credit, was to campaign strenuously in his later life for the reduction of caste barriers in India — a campaign almost invisible in the movie, of course, conveyed in only two glancing references, leaving the audience with the officially sponsored if historically astonishing notion that racism was introduced into India by the British. To present the Gandhi of 1893, a conventional caste Hindu, fresh from caste-ridden India where a Paraiyan could pollute at 64 feet, as the champion of interracial equalitariansim is one of the most brazen hypocrisies I have ever encountered in a serious movie.

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.

August 9, 2018

QotD: Gandhi the man

Gandhi rose early, usually at three-thirty, and before his first bowel movement (during which he received visitors, although possibly not Margaret Bourke-White) he spent two hours in meditation, listening to his “inner voice.” Now Gandhi was an extremely vocal individual, and in addition to spending an hour each day in vigorous walking, another hour spinning at his primitive spinning wheel, another hour at further prayers, another hour being massaged nude by teenage girls, and many hours deciding such things as affairs of state, he produced a quite unconscionable number of articles and speeches and wrote an average of sixty letters a day. All considered, it is not really surprising that his inner voice said different things to him at different times. Despising consistency and never checking his earlier statements, and yet inhumanly obstinate about his position at any given moment, Gandhi is thought by some Indians today (according to V.S. Naipaul) to have been so erratic and unpredictable that he may have delayed Indian independence for twenty-five years.

For Gandhi was an extremely difficult man to work with. He had no partners, only disciples. For members of his ashrams, he dictated every minute of their days, and not only every morsel of food they should eat but when they should eat it. Without ever having heard of a protein or a vitamin, he considered himself an expert on diet, as on most things, and was constantly experimenting. Once when he fell ill, he was found to have been living on a diet of ground-nut butter and lemon juice; British doctors called it malnutrition. And Gandhi had even greater confidence in his abilities as a “nature doctor,” prescribing obligatory cures for his ashramites, such as dried cow-dung powder and various concoctions containing cow dung (the cow, of course, being sacred to the Hindu). And to those he really loved he gave enemas — but again, alas, not to Margaret Bourke-White. Which is too bad, really. For admiring Candice Bergen’s work as I do, I would have been most interested in seeing how she would have experienced this beatitude. The scene might have lived in film history.

There are 400 biographies of Gandhi, and his writings run to 80 volumes, and since he lived to be seventy-nine, and rarely fell silent, there are, as I have indicated, quite a few inconsistencies. The authors of the present movie even acknowledge in a little-noticed opening title that they have made a film only true to Gandhi’s “spirit.” For my part, I do not intend to pick through Gandhi’s writings to make him look like Attila the Hun (although the thought is tempting), but to give a fair, weighted balance of his views, laying stress above all on his actions, and on what he told other men to do when the time for action had come.

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.

August 6, 2018

1918 Flu Pandemic – Leviathan – Extra History – #5

Extra Credits

Published on 4 Aug 2018This is a global pandemic. The flu jumps ship, literally, onto the docks of American Samoa, of South Africa, of Alaska, of India. The 1918 flu infects every human continent.

July 2, 2018

Drowsy Maggie – Scottish Indian Punjabi Mix (The Snake Charmer)

TheSnakeCharmer

Published on 4 Jun 2018When a 200 year old Traditional Scottish Folk song gets a Punjabi Dubstep revival by The Snake Charmer. A multi cultural music video with Britain’s Castles, highland dancers, Bagpipes, Graffiti walls from India, punjabi folk, bhangra dancers, Russian violinist and a crazy dhol player get together to showcase the amazing diversity in the world and how we all have something in common and can contribute to each other despite the distance and differences. Enjoy this brand new Celtic punjabi mix with Bagpipes.

Patreon (Support me for as less as $1) – https://www.patreon.com/thesnakecharmer

GET MP3

iTunes – https://goo.gl/eoszgf

Google Play – https://goo.gl/3sGBgbBagpipes – Archy Jay

Violin – MadinaHighland Dancers – Northumberland Church of England Academy combined cadet Force, Laura Greyson, Whistle School of Highland Dance.

Bhangra Group – https://www.facebook.com/bhangrainspire/

Dhol Player – Sarthak Pahwa

June 27, 2018

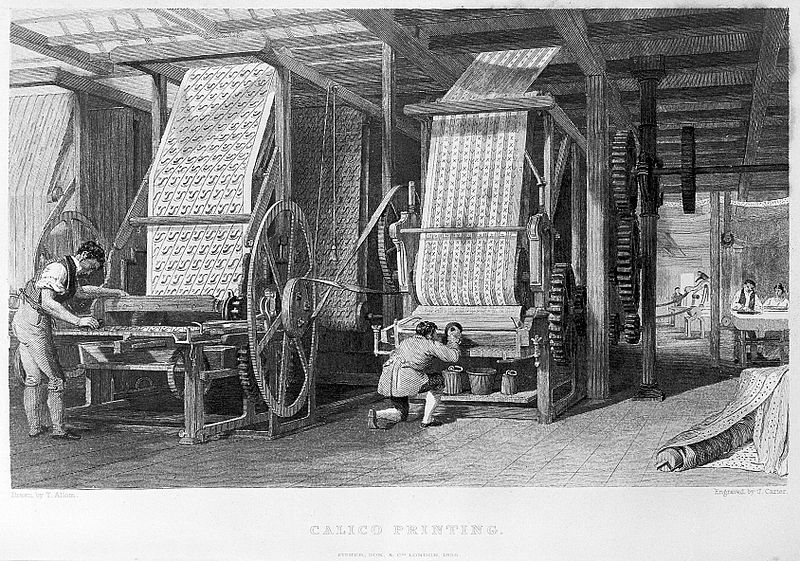

Calico prohibition

In the current issue of Reason, Virginia Postrel outlines an eighteenth-century French government attempt to prohibit calico cloth:

On a shopping trip to the butcher’s, young Miss la Genne wore her new, form-fitting jacket, a stylish cotton print with large brown flowers and red stripes on a white background. It got her arrested.

Another young woman stood in the door of her boss’ wine shop sporting a similar jacket with red flowers. She too was arrested. So were Madame de Ville, the lady Coulange, and Madame Boite. Through the windows of their homes, law enforcement authorities spotted these unlucky women in clothing with red flowers printed on white. They were busted for possession.

It was Paris in 1730, and the printed cotton fabrics known as toiles peintes or indiennes — in English, calicoes, chintzes, or muslins — had been illegal since 1686. It was an extreme version of trade protectionism, designed to shelter French textile producers from Indian cottons. Every few years the authorities would tweak the law, but the fashion refused to die.

Frustrated by rampant smuggling and ubiquitous scofflaws, in 1726 the government increased penalties for traffickers and anyone helping them. Offenders could be sentenced to years in galleys, with violent smugglers put to death. Local authorities were given the power to detain without trial anyone who merely wore the forbidden fabrics or upholstered furniture with them.

“The exasperation of the lawmakers, after forty years of successive edicts and ordinances which had been largely ignored, flouted or circumvented on a wholesale basis, can be sensed in this law,” writes the fashion historian Gillian Crosby in a 2015 dissertation on the ban. Her archival research shows a spike in arrests for simple possession. “Impotent at stopping the cross-border trade, printing or the peddling of goods,” she writes, “government officials concentrated on making an example of individual wearers, in an attempt to halt the fashion.”

They failed.

In the annals of prohibition, the French war on printed fabrics is one of the strangest, most futile, and most extreme chapters. It’s also one of the most intellectually consequential, producing many of the earliest arguments for economic liberalism. “Long before the more famous debates about the liberalisation of the grain trade, about taxation, or even about the monopoly of the French Indies Company, philosophes and Enlightenment political economists saw the calico debate as their first important battleground,” writes the historian Felicia Gottmann in Global Trade, Smuggling, and the Making of Economic Liberalism (Palgrave Macmillan).

June 26, 2018

Saragarhi – The Last Stand – Extra History

Extra Credits

Published on 5 Aug 2017A humble signal station manned by only twenty one Sikh soldiers of the British Empire finds itself beset by 10,000 attackers. There is no hope for relief, but even knowing it will come at the cost of their lives, the Sikhs refuse to stand down.

Twenty one men in the 36th Sikh Regiment stand against thousands of attackers, prepared to make their final stand.

June 25, 2018

QotD: Gandhi and the British army

The film, moreover, does not give the slightest hint as to Gandhi’s attitude toward blacks, and the viewers of Gandhi would naturally suppose that, since the future Great Soul opposed South African discrimination against Indians, he would also oppose South African discrimination against black people. But this is not so. While Gandhi, in South Africa, fought furiously to have Indians recognized as loyal subjects of the British empire, and to have them enjoy the full rights of Englishmen, he had no concern for blacks whatever. In fact, during one of the “Kaffir Wars” he volunteered to organize a brigade of Indians to put down a Zulu rising, and was decorated himself for valor under fire.

For, yes, Gandhi (Sergeant-Major Gandhi) was awarded Victoria’s coveted War Medal. Throughout most of his life Gandhi had the most inordinate admiration for British soldiers, their sense of duty, their discipline and stoicism in defeat (a trait he emulated himself). He marveled that they retreated with heads high, like victors. There was even a time in his life when Gandhi, hardly to be distinguished from Kipling’s Gunga Din, wanted nothing so much as to be a Soldier of the Queen. Since this is not in keeping with the “spirit” of Gandhi, as decided by Pandit Nehru and Indira Gandhi, it is naturally omitted from the movie.

Richard Grenier, “The Gandhi Nobody Knows”, Commentary, 1983-03-01.