In The Conservative Woman, N.S. Lyons continues his essay contending that the arrival of Donald Trump, version 2.0, may finally end the era we’ve been living in since immediately after the end of WW2:

The Long Twentieth Century has been characterized by these three interlinked post-war projects: the progressive opening of societies through the deconstruction of norms and borders, the consolidation of the managerial state, and the hegemony of the liberal international order. The hope was that together they could form the foundation for a world that would finally achieve peace on earth and goodwill between all mankind. That this would be a weak, passionless, undemocratic, intricately micromanaged world of technocratic rationalism was a sacrifice the post-war consensus was willing to make.

That dream didn’t work out, though, because the “strong gods” refused to die.

Mary Harrington recently observed that the Trumpian revolution seems as much archetypal as political, noting that the generally “exultant male response to recent work by Elon Musk and his ‘warband’ of young tech-bros” in dismantling the entrenched bureaucracy is a reflection of what can be “understood archetypally as [their] doing battle against a vast, miasmic foe whose aim is the destruction of masculine heroism as such”. This masculine-inflected spirit was suppressed throughout the Long Twentieth Century, but now it’s back. And it wasn’t, she notes, “as though a proceduralist, managerial civilization affords no scope for horrors of its own”. Thus now “we’re watching in real time as figures such as the hero, the king, the warrior, and the pirate; or indeed various types of antihero, all make their return to the public sphere”.

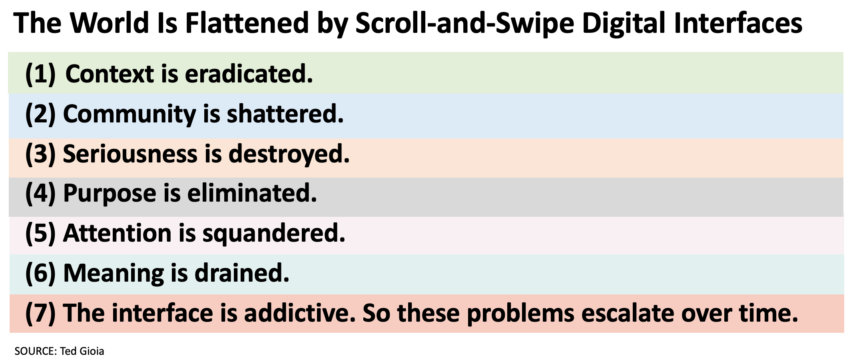

Instead of producing a utopian world of peace and progress, the open society consensus and its soft, weak gods led to civilizational dissolution and despair. As intended, the strong gods of history were banished, religious traditions and moral norms debunked, communal bonds and loyalties weakened, distinctions and borders torn down, and the disciplines of self-governance surrendered to top-down technocratic management. Unsurprisingly, this led to nation-states and a broader civilization that lack the strength to hold themselves together, let alone defend against external threats from non-open, non-delusional societies. In short, the campaign of radical self-negation pursued by the post-war open society consensus functionally became a collective suicide pact by the liberal democracies of the Western world.

But, as reality began to intrude over the past two decades, the share of people still convinced by the hazy promises of the open society steadily diminished. A reaction began to brew, especially among those most divorced from and harmed by its aging obsessions: the young and the working class. The “populism” that is now sweeping the West is best understood as a democratic insistence on the restoration and reintegration of respect for those strong gods capable of grounding, uniting and sustaining societies, including coherent national identities, cohesive natural loyalties, and the recognition of objective and transcendent truths.

Today’s populism is more than just a reaction against decades of elite betrayal and terrible governance (though it is that too); it is a deep, suppressed desire for long-delayed action, to break free from the smothering lethargy imposed by proceduralist managerialism and fight passionately for collective survival and self-interest. It is the return of the political to politics. This demands a restoration of old virtues, including a vital sense of national and civilizational self-worth. And that in turn requires a rejection of the pathological “tyranny of guilt” (as the French philosopher Pascal Bruckner dubbed it) that has gripped the Western mind since 1945. As the power of endless hysterical accusations of “fascism” has gradually faded, we have – for better and worse – begun to witness the end of the Age of Hitler.