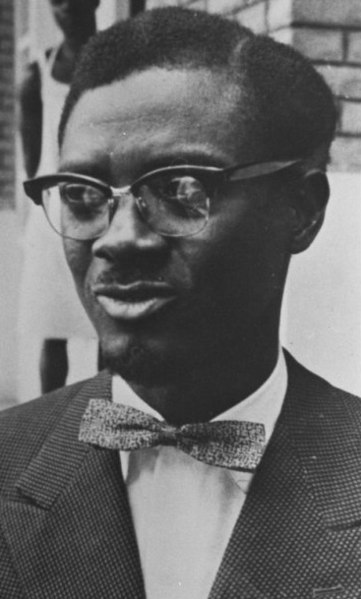

The CIA decided early on that the first democratically elected Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo was being controlled by their Soviet opponents and needed to be killed:

Patrice Émery Lumumba, first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo on 27 December 1960.

Unknown photographer

I’m still making my way through David Talbot’s 2015 book The Devil’s Chessboard, a history that explores the life of CIA Director Allen Dulles and the sordid history of the agency.

There are too many grisly anecdotes to recount showing how the CIA was involved in unlawful and unethical acts all over the world, but one that sticks out was the book’s treatment of Patrice Lumumba, an African nationalist who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo before he was killed in 1961 — with a shove from the CIA.

Lumumba was a thorn in the side of the agency, and his left-leaning politics led CIA officials to believe he was a stooge for the USSR (he wasn’t, as the CIA later admitted). So it was determined that Lumumba had to go—one way or the other.

First, a coup was arranged to have the democratically-elected Lumumba, who was demanding full independence for the Congolese people, removed from office and placed under arrest. To this end, the CIA tapped a young military colonel named Joseph Mobutu, who was friendly with Belgian intelligence (the Congo had long been under Belgian colonial rule) and would go on to rule for decades until he was ousted himself in a 1997 rebellion.

Then the CIA began exploring options to eliminate the popular Lumumba. Being the CIA, a single method was not chosen. Instead, various methods were explored to take out the Congolese leader and multiple people were tapped, including a pair of hitmen the agency had hired from Europe’s criminal underworld.

Talbot explains how the CIA equipped one of these cutthroats with a tube of poisoned toothpaste. Why toothpaste? Because one Dr. Ewen Cameron, at the behest of the CIA, had analyzed Lumumba and noted his immaculate white teeth. This led him to suggest a simple way to eliminate the troublesome leader: poison his dental products.

“In the end, the CIA did not go through with the toothpaste plot,” writes Talbot, “apparently deciding that poisoning a popular leader while he was under UN protective custody in his own house would be too flagrant a deed—one that, if traced back to the agency, would lead to unpleasant international repercussions.”

Instead, days before the inauguration of John F. Kennedy, the CIA arranged to have Lumumba chartered off on a plane to Katanga, a province that had broken from the Congo and was ruled by factions hostile to Lumumba.

This all but sealed Lumumba’s fate, CIA officials later testified.

“I think there was a general assumption, once we learned that he had been sent to Katanga, that his goose was cooked,” CIA station chief James Devlin, who helped orchestrate Lumumba’s fall, quipped to the Church Committee years later.

Devlin was right. During his flight to Katanga, Lumumba was beaten to a pulp. Then he was driven by jeep to a farm and beaten by members of rival political factions. The men, Talbot makes clear, had clear ties to US and Belgian intelligence.

“Eventually he was killed, not by our poisons, but beaten to death, apparently by men who had agency cryptonyms and received agency salaries,” said CIA agent John Stockwell, who was sent to the Congo in the aftermath of the assassination.

The Soviets managed a propaganda win out of the CIA’s clumsy wet work, renaming the Peoples’ Friendship University of the USSR (primarily used for training non-Soviet citizens from “fraternal socialist” and “unaligned” nations in Marxist-Leninist views) to the Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University.