Chris Bray on the sudden discovery of his dissertation topic in a quite unexpected venue:

Fifteen years ago, more or less, I stumbled into a topic for a dissertation when I got frustrated and took a walk. I was in Worcester, Massachusetts, working in the archives at the American Antiquarian Society and finding just absolutely nothing at all that answered my question. So I wandered, and passed a decommissioned armory with a sign over the door that said MASSACHUSETTS MILITARY ARCHIVES. They let me poke around, and by the end of the day I was running around with my hair on fire and shouting at everybody that my dissertation was about something else, now.

State militia courts-martial in the opening decades of a new republic recorded every word, in transcripts that could run to hundreds of pages — frequently interspersed with a line that said something like, “Clerk again reminded witnesses to speak slowly.” The dozen officers who made up a militia court weren’t military professionals, but were instead the prominent farmers and craftsmen who were elected to militia office by their townsmen. So transcripts of state military trials were verbatim discussions among something like the most respected farmers of a county, or of this county and the next one over. They were not recorded debates between the great statesmen of the era. And they needed a big room where a dozen men could sit at a long table in front of the parties and the spectators, so state courts-martial tended to convene in taverns.

One more important thing: The formalization of military courts was way in the future, and there wasn’t a professional JAG Corps in the militia to run trials. State courts-martial were a lawyer-free forum. The accuser was expected to “prosecute” his case — to show up and prove the wrongdoing he had claimed to know about. And defendants were expected to personally defend themselves, questioning witnesses and presenting arguments to the court. At the end of testimony, the “prosecutor” and the defendant personally went home to write their own closing statements, and we still have these documents, tied into the back of the trial transcripts with a ribbon. Courts would stop in the evening and resume in the morning, and men accused of military offenses would show up with twenty-page closing statements in their own handwriting, with holes in the page where the pen poked through.

So: a panel of farmers, serving as local militia officers, listening to an argument between farmers who served as local militia officers, in a tavern, and we have a detailed record of every word they said.

They were magnificent. They were clear, thoughtful, fair, and logical. They had no patience at all for dithering or innuendo; they expected a man who accused another man of wrongdoing to get to it, in an ordered and serious way. Witnesses who fudged or evaded ran into a buzzsaw. The officers on the courts would interject with their own questions: Look, captain, did he say it or didn’t he? And then they wanted a serious summary of the evidence, with a consistent argument. Their thinking was structured, and they expected the same of others.

We distinguish between talking and doing, and between talkers and doers. But these men were doers in the hardest sense. Their families starved or thrived because of their work with tools and the skill in their hands. Their food came from their dirt, outside their front door. They mostly weren’t formally educated; they didn’t spend their young lives going to school. They worked, from childhood. And yet they could talk, meaningfully and carefully. They could address a controversy with measured discourse, gathering as a community to assess an institutional failure and organize a logical response. Their talking was another way of doing.

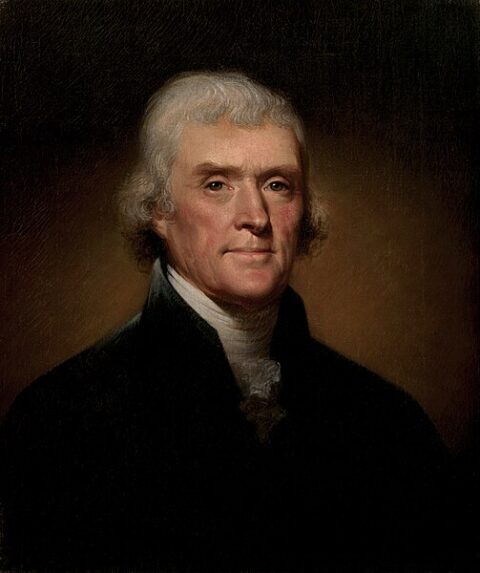

The historian Pauline Maier has written that we think too much of Thomas Jefferson, because we don’t see his cultural context. The Declaration of Independence looks to us like a startling act of political creativity, systematically describing a set of grievances and proposing an ordered response based on a clear philosophy of action. But Jefferson showed up after years of disciplined and thoughtful local proclamations on the crisis, Maier says. He was the national version of a hundred skillful town conventions, standing on the foundation of an ordered society that knew what it believed and what it meant to do about it.