Glenn Reynolds on the way the US government’s structure changed from the “spoils system” of the early republic to the modern “professional” civil service of today:

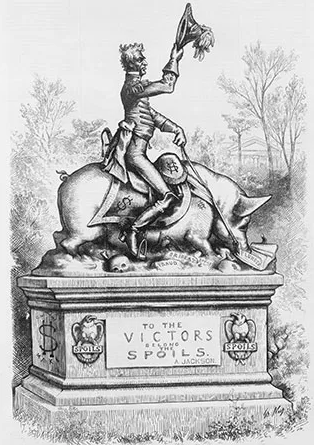

Andrew Jackson sitting on a hog on top of a tomb with the inscription “To the victors belong the spoils”.

Political cartoon by Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, 28 April, 1877.

America’s institutions need structural reform. We need it in academia, we need it in the corporate world, and we need it in government. In all of these fields, the structures, incentives, and institutions that have grown up over time have been destructive, and need to be fundamentally transformed.

I’ll be writing about all of these things down the line, but for now let’s start with government. Though you don’t hear a lot about it on the right, the left is all bent out of shape over the prospect that a Republican administration elected in 2024 might partially deconstruct the existing protected civil service. I, on the other hand, am excited about that prospect, and only wish they’d go farther.

Prior to the adoption of the Pendleton Act in 1883, government employment operated according to the “spoils system”, which meant that hiring in the executive branch was controlled by the Executive. When a new administration came in, everyone’s job was up for grabs, at least potentially. This “rotation in office” had several advantages, which were widely appreciated at the time, and propounded by presidents from Jefferson to Jackson to Lincoln.

Jackson argued that one serving in government for too long would inevitably lose sight of the public interest and come to use office for personal gain. He also maintained that government was or could be made simple enough for men of ordinary ability and experience, so ‘more is lost by the long continuance of men in office than is generally to be gained by their experience’.1

Contrary to popular belief, though, the arrival of a new president didn’t mean that everyone left. Even Andrew Jackson, upon taking office, replaced only about 10% of the federal work force with his own people. Every president understood the value of continuity, and hiring new people is hard work.

But under the spoils system, the fact that the president could replace anyone mean that everyone worked for him. And that meant both that everyone was responsible to the president, and that the president was responsible for everyone in the government, and everything the government did. This is consistent with the Constitution’s vesting clause, which provides that “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” If the executive branch does it, it’s an executive power, and if it’s an executive power it should be controlled by the president.

Contrast this to a “professional” civil service, in which the president does neither the hiring nor the firing, except with regard to a comparatively small number of senior officials. The civil service doesn’t think of itself as working for the president, really, and will happily drag its feet when it doesn’t like the president’s priorities. And when the bureaucracy misbehaves, or fails to perform, the president can, at least to a degree, blame its recalcitrance for the trouble or lack of results that occurs.

Congress is also let off the hook, yet simultaneously weirdly empowered. Congress can blame “the bureaucracy” for bad things, even when those things result from laws that Congress has passed. Then it can turn around and “help” constituents by intervening with the bureaucracy it has rendered dysfunctional, earning gratitude that may be deserved in a narrow sense, but not in terms of the big picture.

Under a spoils system, on the other hand, nobody gets off the hook. If the bureaucracy misbehaves, the president can fire the misbehavers. If Congress is unhappy with what bureaucrats do, they can demand that the president fire them, and make an election issue out of it if they want.

So why did we wind up with a civil service? As is typical, the fantasy of a neutral, efficient, expert civil service was laid next to the reality of a messy functioning government. But, as is also typical, the fantasy in practice turned out to be considerably less appealing than as proposed.

1. Robert Maranto, Thinking the Unthinkable in Public Administration: A Case for Spoils in the Federal Bureaucracy, Administration & Society, January 1998, 623,625.