In Quillette, David Cohen outlines the career of David Bowie:

With impeccable timing, the thin white stork had dropped David Robert Jones out of London’s skies nearly three-score-and-ten years earlier. The suburban Bromley Boomer fell to Earth on January 8th, 1947, and landed smack in the middle of the bulge years, a wonderfully fertile period for anyone looking to forge a career in recorded music. His first instrument was the saxophone, which he was blowing on by the age of 14. Within a few years, the transistor radio would be ubiquitous, young people would be awash with disposable cash to buy records, and the mass adoption of international air travel would open up new vistas for fans and artists alike. Could any moment have been better suited to a rock-star-in-waiting?

But he also came of age as the youngest child in a doomy household. Three of his maternal aunts suffered from acute mental health issues — one of whom was eventually lobotomized — and the family was riven with more dark secrets than the Tolstoy home. His schizophrenic step-brother, Terry, would spend much of his adult life in psychiatric care. His beloved father dropped dead when Bowie was just 22, while his mother — a children’s home publicist with whom he was emphatically not close — lived on. “Everyone says, ‘Oh yes, my family is quite mad,'” Bowie later recalled. “Mine really is.”

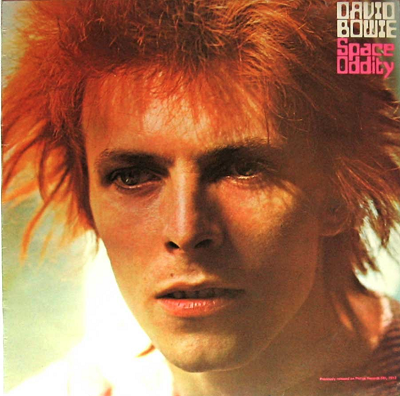

The greatest dream of the era in which Bowie grew up — the promise of putting Man on the Moon — became one of his first signature artistic nightmares. Space Oddity, the most famous track from his eponymous second album, conjured one such scenario, and provided him with his first real hit after the false start of his debut. The earlier album had its moments, but it left unresolved the question of whether the singer wanted to be a fey-voiced Anthony Newley or a strange young man called Dylan.

By the time he recorded his second album — and, especially, his third — Bowie had decided he would be a bit of both. The cover art for 1970’s The Man Who Sold the World presented him elegantly reclining on a chaise longue in a dress. He smoked copious amounts of hash and assembled a crack band for 10 days of whirling Moog synthesizers and hard rock guitars. The experience was so enjoyable and creatively rewarding that bassist Trevor Bolder, guitarist Mick Ronson, and drummer Mick Woodmansey stayed on. The tracks were laid down at a London residence called Haddon Hall, in Beckenham, and it is here that he would write and rehearse the material for his next three albums that would send his career stratospheric.

Commercially, the sex, drugs, and frock ‘n’ roll of The Man Who Sold the World didn’t find much of an audience. It was too heavy, perhaps, for the folk followers he had accrued with its acoustic predecessor. And too gay for rock fans certainly, the singer’s voracious heterosexuality notwithstanding. He followed it a year later with Hunky Dory, which is generally thought to be the record on which the Bowie alchemy first cohered into something truly new. It was also the curtain-raiser for what’s generally regarded as his classic period, and it provided him with his first American hit, “Changes”. More critically, it saw him discard the claustrophobic sound of The Man Who Sold the World for textured melodies, creamy arrangements, seat-of-the-pants lyrics, and further cameos from extraterrestrials.

On Hunky Dory, Bowie also turned in tribute tracks about Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, and Bob Dylan. Warhol hated the song Bowie had written about him. Reed would eventually smack Bowie about the head during an altercation at a London restaurant in April 1979. And when Bowie finally met Dylan, he later told Playboy, they “didn’t have a lot to talk about. We’re not great friends. Actually, I think he hates me.” Small wonder that he preferred the company of spacemen. The razzle-dazzle of “Oh! You Pretty Things” conjures hordes of them. As does “Life on Mars?” which features a chord progression nicked from Frank Sinatra’s “My Way”. The album closes with “The Bewlay Brothers”, in which the 24-year-old singer paid a tribute of sorts to his own step-brother, Terry.

But it was the release of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars in 1972 that made David Bowie a superstar. Picking the space songs out of that record is difficult because, by that point, almost everything Bowie was writing seemed to have an explicitly alien streak. During his appearance on Top of the Pops, he draped an arm across Ronson’s shoulders, and glowered out at a world that was about to repay the attention. In the wake of the album’s release, he returned to the United States a sensation (although the stormy flight en route only confirmed his fear of flying).

A generation on, Ziggy Stardust still routinely appears at or near the top of critics’ lists of the all-time greatest rock albums. It is strange to recall then, that in 1972, while it picked up its share of warm reviews, the album was by no means universally well received (the work of a “competent plagiarist”, sniffed Sounds). Some critics never got it. “I always thought all that Ziggy Stardust homo-from-Aldebaran business was a crock of shit,” wrote Lester Bangs in Creem four years later, “especially coming from a guy who wouldn’t even get in a goddam airplane.”