In Quillette, Jonathan Kay put together “a somewhat lengthy manifesto” on the topic of cultural appropriation in response to a request from Robert Jago who wanted to do an interview with Kay on this issue:

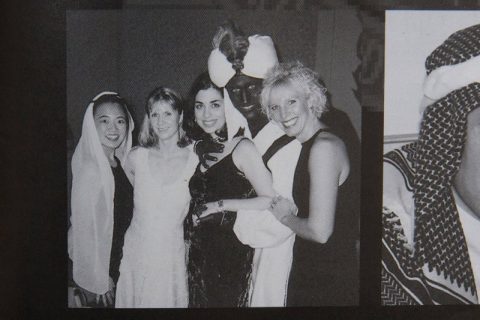

Justin Trudeau (Canada’s most prolific cultural appropriator) with dark makeup on his face, neck and hands at a 2001 “Arabian Nights”-themed party at the West Point Grey Academy, the private school where he taught.

Photo from the West Point Grey Academy yearbook, via Time

“Cultural appropriation” typically gets defined in a way that depends on whether one is defending it or denouncing it. If you’re defending it, you prefer to look at the big picture: Every new kind of art form, literary genre, style of dress, or cuisine typically represents a mix of inherited and borrowed elements. Shakespeare’s sonnets were written in an Iambic pentameter that Chaucer had “appropriated” from the French and Italians. So if Indigenous or African poets want to appropriate it from the English, no one has any basis for complaint. If you define cultural appropriation in this big-picture way, the concept isn’t just permissible. It’s artistically necessary, and indeed inevitable.

But if you’re denouncing cultural appropriation, on the other hand, the argument is more persuasive when your frame of reference is small, local, and community-rooted. I’m thinking of the (white) novelist or film director who passes through a region, and hears some garbled version of folklore that relates to a nearby Indigenous community. The guy thinks, “Oh wow, that’ll make a great novel” (or TV show, movie, etc.), and then makes a mint without consulting (let alone cashing in) the Indigenous community.

So the debate over cultural appropriation is like a lot of debates: It’s really easy to win if you get to define the terms. And since both sides pick definitions that suit them, it can become a dialogue of the deaf.

Indeed, there’s often no dialogue at all. Rather, both sides are apt to retreat into apocalyptic language about, respectively, (a) totalitarian censorship, and (b) white supremacist (cultural) genocide. This is absolutist language that leaves no room for nuance or discussion.

The cultural-universalism side of this dialogue is represented by people like me. I write about every topic under the sun, and so I get my back up when someone tells me that I’ve got to “stay in my lane”. My whole career is built around hopscotching from one idea to the next without worrying (much) about who gets offended. For me, the imposition of rules on what people are allowed to write about isn’t just an annoyance. It’s an existential threat to the creative faculties.

But if you’re on the other end of this — say, you’re a member of a small Indigenous community whose history and folklore have yet to be recorded or celebrated in any definitive form — you don’t care about some white guy in Toronto whining about how he can’t do the equivalent of wearing a sombrero on Cinco de Mayo. A small First Nations community might get only one real shot at telling its story to the world. If that shot gets used up by an outsider who strip-mines the locals’ oral history for a bestseller, that can no doubt feel like existential threat to one’s cultural autonomy. It’s like: “So you took our land, punished us for using our own language, sent our kids to residential schools, and now all we really have left is our culture, and you want to steal that, too?”

There’s this trite expression that often gets trotted out these days: Intent doesn’t matter, only the harm you cause. But of course, intent does matter. And if an author, director, or artist intends to respectfully and accurately include a community’s story in his or her work, then, for me, that’s very much a mark in their favour. That said, I absolutely do not think that this means there is an obligation to “honour” or “uplift” the community in question — let alone express “solidarity” or “allyship” with them. Doing so means you’re writing activist propaganda. What I mean, rather, is that you shouldn’t be intending to mock or belittle whole swathes of humanity.

The problem is that, in Canadian cultural circles at least, this isn’t really the standard that’s applied. I’ve spoken to a number of Canadian writers who, out of the best of intentions, invest their own funds in “sensitivity readers” — a process that can be not only expensive and time-consuming, but also creatively ruinous, since these consultants often are bursting with ideas about how to turn your novel or movie into a specimen of the above-referenced activist propaganda. I know one woman, in particular — a novelist — who appeared before a First Nations tribal council, and got its official permission to include a character in her book whose identity related to their community. But then a community member, someone not even involved with the band leadership, went after the woman and tried to smear her as racist. This is after she’d dotted every I and crossed every T of the sensitivity-reader process.