In The Critic, Ben Woodfinden discusses the maple-flavoured slippery slope we’re gaining speed on: what’s known as “Medical Assistance In Dying (MAID)”:

Canada is widely seen as one of the world’s most progressive nations in the world, “leading the way” (depending on where you stand) on a variety of social issues. But in recent months, Canada has been garnering some less than savoury international attention because of the dark side of one of its recent progressive accomplishments, namely the assisted suicide regime that has been created since the Supreme Court struck down prohibitions on assisted suicide in 2015. The tragic situation that has developed in Canada offers a warning to Britain and other countries considering going down a similar path, both to be cautious about opening the assisted suicide floodgates and about empowering judges to decide whether such things should be allowed.

When Canada’s enlightened judicial philsopher kings and queens overturned criminal prohibitions on assisted suicide in Carter v. Canada, they overturned their own precedent. In 1993 a majority of the Supreme Court found that the criminal code provisions that prohibited assisted suicide did not ultimately violate the Canadian Charter. In 2015 the Court changed its mind. The law didn’t change, of course, but the court decided that “the matrix of legislative and social facts” surrounding the case had changed. Thus the interpretation of constitutional rights must change with them.

Plenty of the same people who were outraged that the United States Supreme Court would overturn precedent on seminal abortion decisions, seemingly had no problem with the overturning of precedent in this Canadian case. This is because implicit in the view of rights and judicial review that many progressives hold, is that it is perfectly acceptable to overturn precedent in the name of expanding or establishing some newly discovered right — but once this is done, the debate is settled and there can be no reasonable dissent or change of heart. History, it seems, only marches in one direction.

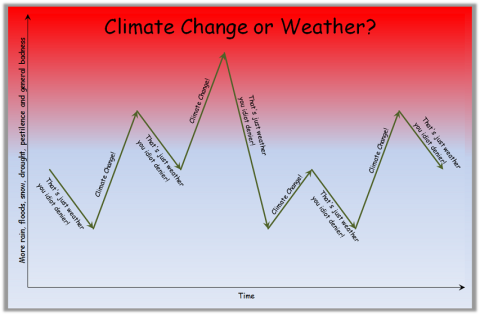

An important part of the Carter decision, where the court determined that relevant social facts had changed, was essentially a blithe dismissal of exactly what has come to pass in Canada less than a decade after the decision. The court rejected the concern that once assisted suicide was allowed in some rare cases, there would be a “slippery slope” from helping terminally ill people end their lives, to a system in which vulnerable people like the disabled were caught in a euthanising net.

Evidence presented in the case by a medical expert from Belgium that this might be possible, was dismissed by the court because “the permissive regime in Belgium is the product of a very different medico-legal culture”. Unlike those barbaric Belgians, enlightened Canada could avoid sliding down this slippery slope in which safeguards are easily gotten around. They would avoid the creeping expansion of eligibility by setting up a “carefully regulated scheme” that would keep its application narrow and exceptional.

Spoiler: No. No, we didn’t.