Real Time History

Published 24 Mar 2022Get Nebula and CuriosityStream in a great bundle deal: https://curiositystream.com/realtimeh…

In the beginning of Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, the Russian Tsar Alexander I was under pressure to rally his people. A month into the campaign he declared the The Patriotic War (Отечественная война) to fight back Napoleon — who was already having serious supply issues and a deteriorating logistics network.

» SUPPORT US ON PATREON

https://patreon.com/realtimehistory» THANK YOU TO OUR CO-PRODUCERS

John Ozment, James Darcangelo, Jacob Carter Landt, Thomas Brendan, Kurt Gillies, Scott Deederly, John Belland, Adam Smith, Taylor Allen, Rustem Sharipov, Christoph Wolf, Simen Røste, Marcus Bondura, Ramon Rijkhoek, Theodore Patrick Shannon, Philip Schoffman, Avi Woolf,» SOURCES

Boudon, Jacques-Olivier. Napoléon et la campagne de Russie en 1812. 2021.

Chandler, David. The Campaigns of Napoleon, Volume 1. New York 1966.

Clausewitz, Carl von. Hinterlassene Werke des Generals Carl von Clausewitz über Krieg und Kriegsführung. Siebenter Band, Der Feldzug von 1812 in Rußland, der Feldzug von 1813 bis zum Waffenstillstand und der Feldzug von 1814 in Frankreich. Berlin 1835.

Geschichte der Kriege in Europa seit dem Jahre 1792 als Folgen der Staatsveränderung in Frankreich unter König Ludwig XVI., neunter Teil, 1. Band. Berlin 1839.

Hartwich, Julius von. 1812. Der Feldzug in Kurland. Nach den Tagebüchern und Briefen des Leutnants Julius v. Hartwich. Berlin 1910.

Holzhausen, Paul. Die Deutschen in Russland 1812. Leben und Leiden auf der Moskauer Heerfahrt. Berlin 1912.

Lieven, Dominic. Russia Against Napoleon. 2010.

Mikaberidze, Alexander. “The Lion of the Russian Army”: Life and Military Career of General Prince Peter Bagration 1765-1812. PhD Dissertation, 2003.

Rey, Marie-Pierre. L’effroyable tragédie: une nouvelle histoire de la campagne de Russie. 2012.

Robson, Martin. A History of the Royal Navy: the Napoleonic Wars. 2014.

Tagebuch des Königlich Preußischen Armeekorps unter Befehl des General-Leutnants von Yorck im Feldzug von 1812. Berlin 1823.

Zamoyski, Adam. 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March on Moscow. 2005.

Безотосный В. М. Россия в наполеоновских войнах 1805–1815 гг. (Москва: Политическая энциклопедия, 2014)

Отечественная война 1812 года. Энциклопедия (Москва: РОССПЭН, 2004)» OUR STORE

Website: https://realtimehistory.net»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Above Zero

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Toni Steller

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Digital Maps: Canadian Research and Mapping Association (CRMA)

Research by: Sofia Shiogorova, Jesse Alexander

Fact checking: Florian WittigChannel Design: Simon Buckmaster

Contains licensed material by getty images

Maps: MapTiler/OpenStreetMap Contributors & GEOlayers3

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2022

March 25, 2022

All-Out War Against Napoleon – The Grand Manifesto of Alexander I

Jordan Peterson — noted collector of early Soviet art

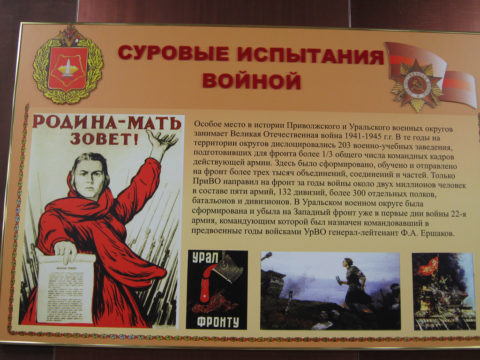

Jordan Peterson is probably the second-most polarizing living Canadian — after Justin the Lesser, of course — but his collection of early Soviet art and propaganda posters is perhaps one of the more surprising things about him:

“Mother Russia” by topsafari is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

I’ve been in homes that have displayed unusual artwork, including one house decorated in African-themed pieces that many would consider pornographic. But I don’t believe I’ve ever seen anything quite as unusual and unique as the art in Jordan Peterson’s home.

To be clear, I’ve never actually visited Peterson’s house. But his home and its artwork are described in some detail by Norman Doidge, who wrote the foreword to Peterson’s best-selling book 12 Rules for Life.

Doidge met Peterson in 2004 at a gathering hosted by mutual friends, a pair of Polish emigres who came of age during the days of the Soviet empire. At the time, Peterson was a professor at the University of Toronto, and he and Doidge — a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst — soon became friends. (Apart from their scientific interests, it seems the men shared a passion for the great books, particularly “soulful Russian novels”.)

Doidge visited Peterson on more than one occasion, and he describes the Peterson house as “the most fascinating and shocking middle-class home I had seen.” Among the fascinations was an impressive collection of unusual artwork.

“They had art, some carved masks, and abstract portraits, but they were overwhelmed by a huge collection of original Socialist Realist paintings of Lenin and the early Communists commissioned by the USSR,” writes Doidge. “Paintings lionizing the Soviet revolutionary spirit completely filled every single wall, the ceilings, even the bathrooms.”

Books and art can tell you a great deal about people, as I said, but one must be careful to not draw the wrong conclusions. Which invites an important question: Why was Peterson’s home covered in Soviet era artwork?

One might assume that Peterson was a socialist. Yet, this is not the case. Or maybe, one might guess, Peterson began gobbling up Soviet propaganda pieces following the fall of the Soviet Union simply as investment. (I wish I had possessed the foresight to buy up a bunch of vintage Soviet art following the fall of the Soviet empire; alas, I was only 12.) Perhaps, but this wouldn’t explain why it’s displayed throughout his home.

Fortunately, Doidge offers us an answer.

“The paintings were not there because Jordan had any totalitarian sympathies, but because he wanted to remind himself of something he knew he and everyone else would rather forget: that over a hundred million people were murdered in the name of utopia,” Doidge writes.

Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow; Footage from its first flight

Polyus Studios

Published 7 Jul 2020Full documentary is still in development, enjoy the teaser!

(more…)

QotD: Herodotus as Spartan propagandist

The greatest military asset the Spartans had was not actual military excellence – although, again, Spartan capabilities seem to have been somewhat better than average – but the perception of military excellence.

Herodotus seems to be at the start of it, at least in our sources – he relates a story where, after an embarrassing failure in an effort to reduce tiny Tegea to helotage (the Tegeans kicked the Spartans’ asses) in the mid-sixth century, the Spartans supposedly stole the bones of the hero Orestes. Consequently, Herodotus notes, the Spartans were from that point on able to always beat Tegea and subdued the Peloponnese (Hdt. 1.68), resulting in the creation of the Spartan-led Peloponnesian League. The unbeatable Spartans thus appear. It’s possible the Spartan reputation predated this, but – as we’ll see – Herodotus will be the one who codifies that reputation and cements it.

Except, hold on a minute – how hard was it to subdue the Peloponnese? It seems to have been done with a fairly adept mix of diplomacy and military force (champion one side in a local dispute, beat the other, force both into your alliance, repeat, see Kennell (2010), 51-3 for details). But it is little surprise that Sparta would be dominant in the Peloponnese. Messenia and Laconia together was around 2,600 square miles or so. This is – if you’ll pardon the expression – flippin’ massive by the standards of Greek poleis. More than twice as large as the next largest polis in all of Greece (Athens). Sparta is fully one-third of the Peloponnese (the peninsula Sparta is located on). The remaining two-thirds is home to many other poleis – Corinth, Argos, Elis, Tegea, Mantinea, Troezen, Sicyon, Lepreum, Aigeira and on and on. Needless to say, Sparta was several times larger than all of them – only Corinth and Argos came even remotely close in size. The population differences seem to have roughly followed land area. Sparta was just much, MUCH larger and more powerful than any nearby state by the start of the fifth century.

Sparta thus spends the back half of the 500s as the teenager beating up all of the little kids in the sandbox and making himself leader. When you are upwards of three times larger (and in some cases, upwards of ten times larger) than your rivals, a reputation for victory should not be hard to achieve. And, in the event, it turns out it wasn’t.

Which brings us back to Herodotus […] because he isn’t just observing the Spartan reputation, Herodotus is manufacturing the Spartan reputation. Herodotus is our main source for early Greek history (read: pre-480) and for the two Persian invasions of Greece. Herodotus’ Histories cover a range of places and topics – Persia, Greece, Scythia, Egypt – and contain a mixture of history, ethnography, mythology and straight up falsehoods. But – as François Hartog famously pointed out in his The Mirror of Herodotus (originally in French as Le Miroir d’Hérodote), Herodotus is writing about Greece, even when he is writing about Persia – those other cultures and places exist to provide contrasts to the things that Herodotus thinks bind all of the fractious and fiercely independent Greek poleis. And he is perfectly willing to manufacture the past to make it fit that vision.

Sparta has a role to play in that narrative: the well-governed polis, a bastion of freedom, ever opposed to tyranny, be it Greek or Persian. We’ll come back to Sparta’s … let’s say relationship … with Persian “tyranny” next week. But for Herodotus, Sparta is the expression of an ideal form of “Greekness” and in Herodotus’ logic, being well-governed (eunomia is the Greek term) results primarily in military excellence. For the story Herodotus is telling to work, Sparta – as one of the leading states resisting Persia – must be well governed and it must be militarily excellent. That’s what will make a good story – and Herodotus never lets the facts get in the way of a good story.

(Sidenote: Athens – at least post-Cleisthenic Athens – gets this treatment too. Athens ends up embodying a different set of “Greek” virtues and where Sparta shows its prowess on land, the Athenians do so at sea.)

And so, Herodotus – the myth-maker – talks up the Spartiates at Thermopylae (you know, the brave 300) and quietly leaves out the other Laconians (who, if you scrutinize his numbers, he knows must be there, to the tune of c. 900 men), downplaying the other Greeks. Spartan leadership is lionized, even when it makes stupid mistakes (Thermopylae, to be clear, was a military disaster and Spartan intransigence nearly loses the battle of Plataea, but Herodotus represents this as boldness in the face of the enemy; even more fantastically inept was the initial Spartan plan to hold on the Isthmus of Corinth as if no one had ever seen a boat before).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: This. Isn’t. Sparta. Part VI: Spartan Battle”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2019-09-20.