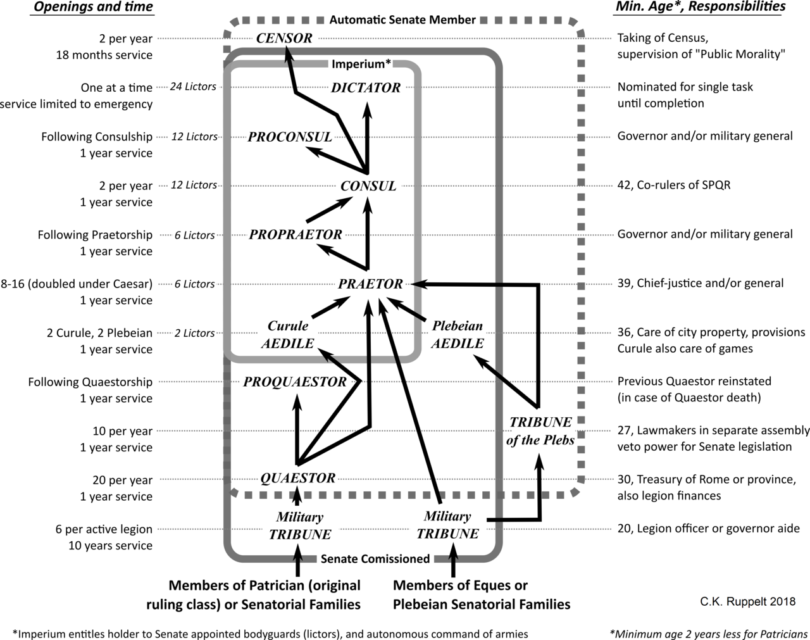

At Founding Questions, Severian notes that the Cursus Honorum — the formal “career path” for ambitious men in the late Roman Republic was a remarkably effective process … that ended up being a victim of its own success:

Ahhh, God bless the autists at Wiki, they’ve got it down to a chart:

This is from Caesar’s time, and since one of this blog’s main themes is the confusion between process and outcome, let’s put it right up front: This system, the cursus honorum, was designed to produce men like Julius Caesar …

… and you can take that in either sense.

Caesar is one of the most mulled-over men in history, but nobody seriously doubts that he was at least competent at pretty much everything. Maybe he didn’t make the big list of “Greatest Pontifices Maximi” (or however the Latin goes), but he wasn’t a disgrace to the toga, either. If it was a public function in the Late Roman Republic, Caesar was at least decent at it.

And that’s what the cursus honorum was designed to do. It was a three-fer: It gave you competent public officials, but it also gave young ruling class men some seasoning. Most importantly, it was a way of nurturing talent that also hedged against the Peter Principle. If you want to argue that that makes it a four-fer, go nuts, but the point is, it was a pretty good system … up to a point, and if you’re a regular reader, you know what that point is: The Dunbar Number, at which point relationships become too complex to be managed personally, and bureaucratic structures replace them.

One wishes later governments had something like this — if a guy starts out as a quaestor and discovers he can’t handle it, he’ll bring that knowledge with him to the Senate. (Of course, if he can’t even manage to get elected to that, he’ll know full well his level of talent, and he’ll sit down and shut up on the Senate’s back benches). Note too that the bottom rung is military service — since at that time legionaries were all militia, the voters got a good look at you where it really matters, right from the beginning.

By the time a man reaches the top, then, he has intimate experience of ALL the public offices. Not only that, but he’s well known to everyone who matters, since in between the various offices he’s in the Senate, making connections (or out in the provinces, making other — but no less valuable — connections). A consul, then, is pretty much by definition omnicompetent. He did a good enough job in all the previous public offices that he didn’t disqualify himself for the top slot. Also, he’s been thoroughly vetted — everyone who matters, at pretty much every level of society, has had a good look at him (or, at worst, has a good friend who has had a good look at him).

Obviously it wasn’t a perfect system. Rome had her share of inept consuls, because people are people and sometimes “promotion to your level of incompetence” means “promotion to the very top job”. But for the most part it worked well, and even if a guy turned out to be a dud as consul, well, what can you do? Everyone had at least a reasonable expectation that he’d be able to handle it, which is pretty much the best one can consistently achieve in human affairs. Not only that, but because of the candidate’s long experience and careful vetting, you had a much better than average chance of getting a real winner …

… a man like Caesar, who is at minimum competent at everything, and outstanding at lots of things.

It’s like Netflix for history… Sign up to History Hit, the world’s best history documentary service and get 50% off using the code ‘TIMELINE’

It’s like Netflix for history… Sign up to History Hit, the world’s best history documentary service and get 50% off using the code ‘TIMELINE’