In Quillette, Will Storr recounts some harrowing early life experiences for three young men ‐ that read like setups for bad horror novels — and how those early humiliations led to tragedy:

If life is a status game, what happens when all our status is taken from us? What happens when we’re made to feel like nothing, again and again and again? Humiliation can be seen as the opposite of status, the hell to its heaven. Like status, humiliation comes from other people. Like status, it involves their judgement of our place in the social rankings. Like status, the higher they sit in the rankings, and the more of them there are, the more powerful their judgement. And, like status, it matters. Humiliation has been described by researchers as “the nuclear bomb of the emotions” and has been shown to cause major depressions, suicidal states, psychosis, extreme rage, and severe anxiety, “including ones characteristic of post traumatic stress disorder.” Criminal violence expert Professor James Gilligan describes the experience of humiliation as an “annihilation of the self.” His decades of research in prisons and prison hospitals, seeking the causes of violence, led him to “a psychological truth exemplified by the fact that one after another of the most violent men I have worked with over the years have described to me how they had been humiliated repeatedly throughout their childhoods.”

The logic of the status game dictates that humiliation must be uniquely catastrophic. For psychologists Professor Raymond Bergner and Dr Walter Torres humiliation is an absolute purging of status and the ability to claim it. They propose four preconditions for an episode to count as humiliating. Firstly, we should believe, as most of us do, that we’re deserving of status. Secondly, humiliating incidents are public. Thirdly, the person doing the degrading must themselves have some modicum of status. And finally, the stinger: the “rejection of the status to claim status.” Or, from our perspective, rejection from the status game entirely.

In severe states of humiliation, we tumble so spectacularly down the rankings that we’re no longer considered a useful co-player. So we’re gone, exiled, cancelled. Connection to our kin is severed. “The critical nature of this element is hard to overstate,” they write. “When humiliation annuls the status of individuals to claim status, they are in essence denied eligibility to recover the status they have lost.” If humans are players, programmed to seek connection and status, humiliation insults both our deepest needs. And there’s nothing we can do about it. “They have effectively lost the voice to make claims within the relevant community and especially to make counterclaims on their own behalf to remove their humiliation.” The only way to recover is to find a new game even if that means rebuilding an entire life and self. “Many humiliated individuals find it necessary to move to another community to recover their status, or more broadly, to reconstruct their lives.”

But there is one other option. An African proverb says, “the child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.” If the game rejects you, you can return in dominance as a vengeful god, using deadly violence to force the game to attend to you in humility. The life’s work of Professor Gilligan led him to conclude the fundamental cause of most human violence is the “wish to ward off or eliminate the feeling of shame and humiliation and replace it with its opposite, the feeling of pride.”

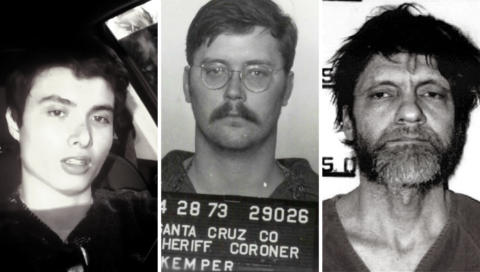

Of course, it would be naive to claim Ed, Ted, and Elliot were triggered solely as a response to humiliation. If the cauterisation of status was a simple mass killing switch, such crimes would be common. Various further contributory factors are possible. All three were men, which dramatically increases the likelihood they’d seek to restore their lost status with violence. Elliot Rodger was said to be on the autism spectrum, which might’ve impacted his ability to make friends and girlfriends; a court psychiatrist claimed Ed Kemper had paranoid schizophrenia (although this remains contested); and Kaczynski’s brother said Ted once “showed indications of schizophrenia.” But none of these conditions are answers in themselves, because the vast majority of those that have them don’t burn down their villages.

The ordeal endured by Kaczynski as a teen at Harvard beggars the imagination and could easily provide conspiracy theorists with copious confirmations of their fears: “What Ted didn’t know was that Murray had a history of working on behalf of secretive government agencies. This would be a study of harsh interrogation techniques, specifically the ‘effects of emotional and psychological trauma on unwitting human subjects.’ Once he’d detailed his secrets and philosophies, Ted was led into a brightly lit room, had wires and probes attached to him, and was sat in front of a one way mirror. There began a series of what Murray called ‘vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive’ attacks on his personal history and the rules and symbols by which he lived and hoped to live. ‘Every week for three years, someone met with him to verbally abuse him and humiliate him,’ Ted’s brother said. ‘He never told us about the experiments, but we noticed how he changed.’ Ted himself described the humiliation experiments as ‘the worst experience of my life.'”