In an Areo article from last year, Alexander Adams discusses the phenomenon of iconoclasm:

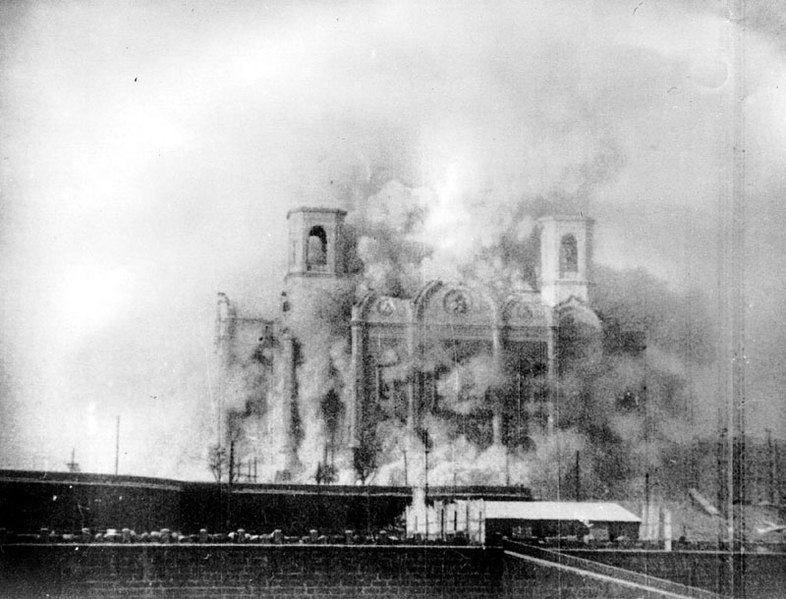

The 1931 demolition of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow.

Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

Behind any campaign is the campaigner: the activist convinced of his own righteousness.

The political activist reserves to himself the right to retrospectively edit our history for his satisfaction by removing monuments, those fixtures of civic life, embedded in the memories of generations. The activist often knows almost nothing about the object of his hatred — merely a garbled caricature of a person caught up in the conditions of her age — but the activist acts as if he were not also caught up in the conditions of his own age.

Iconoclasm is an expression of domination and a demonstration of willingness to act — illegally and unethically — to impose the will of one group over an entire population. It asserts control over all aspects of society. It sets a challenge that will elicit a strong reaction. Iconoclasm is a warning that the protection of law and social conventions no longer applies and that the cause will be promoted through physical force if necessary.

The campaigner argues that public art, accumulated piecemeal over 1,000 years of history, must reflect our society and values today — even if that means altering or erasing stories of the values our past society expressed via its monuments, or suppressing evidence of how we arrived at our current situation. The left-wing activist wants to celebrate current-day multiculturalism, but mostly he wants to erase evidence of the historic monoculturalism that preceded it.

Our willingness to live with historical relics we feel ambivalence towards is a demonstration of our toleration of dissent. Likewise, an openness to imagining ourselves in past times — constrained by the conventions and laws of a different era — forces us to question common assumptions about the completeness of our knowledge and our moral certainty. If we can make this leap of empathy, we can free ourselves of ideological possession. We have the ability to empathize with both slave and slave owner. Empathy makes it harder to justify destruction of the cultural relics of an older age or silence the voices of individuals, who might share insights into life.

The toleration we extend towards symbols of former regimes and proponents of ideas with which we disagree shows our willingness to be honest about our nations’ pasts. To accept our flaws as a necessary part of our development is to display the maturity, restraint and empathy that define the confident yet self-critical nation. For if we cannot stand the sight of a dead political opponent carved in stone, how can we restrain ourselves in the face of a living political opponent who speaks against us?