Chris Selley on the viewing-with-alarm concerns that we don’t have a single nation-wide standard of care, and why the Swedish approach to the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic is worth observing closely:

Front view of Toronto General Hospital in 2005. The new wing, as shown in the photograph, was completed in 2002.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

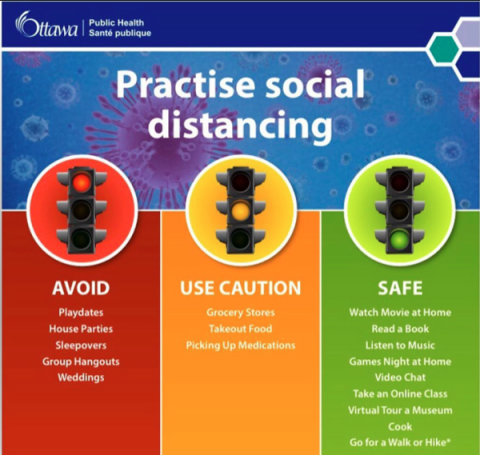

Last week, Maclean’s reported on a group of University of Ottawa researchers who had found, to their consternation, that each province offers different advice to people who think they might be showing coronavirus symptoms. “Even in a cross-Canada pandemic as devastating as this, there is not a single, evidence-based Canadian standard of care simply for self-assessment,” the researchers wrote.

It’s strange how many Canadians seem uncomfortable with the most basic design of their country, which is that of a federation. What the U of O researchers find alarming is not just a matter of Canada operating as it was intended to operate, but also a good example of the benefits. Provinces and territories can shape their responses to the needs of their populations. They can learn from each other what works. It’s a living laboratory.

In the same vein, assuming things don’t go catastrophically wrong, we should be thankful that Sweden is sticking to its guns in avoiding a total lockdown. That, too, will provide very useful data in preparation for COVID-the-next.

It is important to realize that lockdowns take a human toll, sometimes fatal, just like coronaviruses (though probably not on the same scale). Emergency room doctors are worried about their lack of business nowadays, the National Post‘s Richard Warnica reported Friday. “Doctors believe … patients who are afraid of contracting COVID-19 are just waiting (to seek treatment) and getting sicker,” Warnica reported. The head of a Vancouver ER department noted that opioid overdose deaths are up, even as his hospital treats far fewer. Are they overdosing alone, whereas before they might have been saved? When we postmortem this pandemic, we will hear about sexual and domestic assaults, suicides and other isolation-related harms. They will need to be weighed against the risks inherent in a less draconian approach.

Sweden’s strategy has been somewhat caricatured. High schools and universities closed; people aged 70 or older were advised to self-isolate; large gatherings ceased. Easter travel was down a reported 90 per cent. More Swedes have reportedly filed for unemployment benefits than during 2008 crash. Restaurants, pubs and cafés remain open, which seems unfathomable to a Canadian. But “it’s a myth that it’s business as usual,” as Sweden’s deputy prime minister Isabella Lovin told the Financial Times this week.