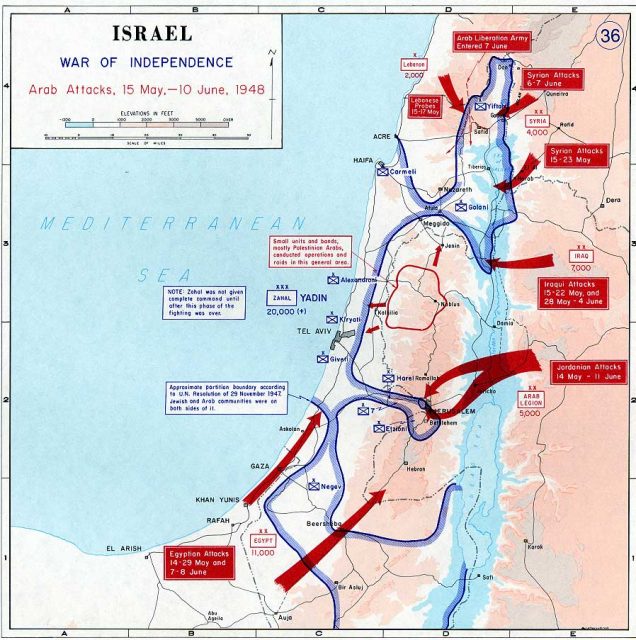

Wilf and Schwartz’s comprehensive history of the refugee issue begins with the UN’s adoption in November 1947 of a plan to partition British Mandatory Palestine into an Arab state and a slightly smaller Jewish state. Violence erupted shortly after, and once the British left the territory, hostilities escalated into a full-scale war, during which fighting between the Zionist movement’s Haganah defense force and various Palestinian Arab militias was followed by an invasion by the surrounding Arab countries. Israel prevailed with truncated borders, but the Arab world remained steadfastly committed to the new state’s elimination. Refugees are a byproduct of every military conflict, but the exodus of the Palestinian Arabs would have uniquely consequential ramifications that continue to haunt the conflict and thwart its resolution to this day.

It is now fashionable for historians sympathetic to the Palestinian narrative to downplay the threat that the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine — the Yishuv — faced in the 1948 conflict. Wilf and Schwartz show conclusively that such attempts, be they sincere or dishonest, are simply untrue. The secretary-general of the Arab League, they note, openly stated that the war was intended to be genocidal, saying, “This will be a war of extermination and momentous massacre, which will be spoken of like the Mongolian massacre and the Crusades.” Meanwhile, the Palestinian Arabs’ most influential leader, the Nazi collaborator Mufti Hajj Amin al-Husseini, said the Arabs would “continue to fight until the Zionists are eliminated, and the whole of Palestine is a purely Arab state.”

Correctly believing that their individual and collective existence were threatened, the Zionist militias, which eventually coalesced into the nascent Israel Defense Forces, sometimes destroyed villages and expelled their inhabitants, and there was a mass flight of Arabs from cities like Haifa and Jaffa. By the end of the war, what emerged was a Jewish state with a comfortable Jewish majority along with a substantial though not overwhelming Arab minority. The refugees, for the most part, were settled in camps in the surrounding Arab nations of Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, as well as in the West Bank and Gaza, which were occupied by Jordan and Egypt, respectively. Jordan alone granted the refugees citizenship and absorbed them into the general population. Elsewhere, however, refugees remained stateless, left to the tender mercies of the international community.

From the beginning, pressure was brought to bear on Israel to allow the refugees to return, and from the beginning Israel steadfastly refused to do so, believing that it would destroy Israel’s Jewish character and precipitate another, perhaps even more brutal war. Wilf and Schwartz reveal that this was in fact precisely the Arabs’ intention. The Arab media spoke openly of establishing a “fifth column” within Israel by repatriating the refugees, and the authors record Palestinian historian Rashid Khalidi’s view that the Arab mood at the time made it clear that the right of return “was clearly premised” on “the dissolution of Israel.” In addition, the Palestinian leadership was initially unenthusiastic about the return of refugees, which they believed would imply a recognition of Israel’s existence to which they remained implacably opposed. For a society deeply rooted in concepts of honor, dignity, and humiliation, such an acknowledgement of defeat was simply unthinkable.

Contrary to the claims of Israel’s opponents, Wilf and Schwartz persuasively argue that the new state was under no moral or legal obligation to allow the refugees to return. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, the concept of population exchange between belligerent national groups in conflict over territory was considered lamentable but inevitable. Consequently, the laws pertaining to refugees often forbade the opposite: States could not force refugees to return to places when to do so might cause further conflict or instability. Emphasis was therefore on resettlement in host countries, usually with a corresponding ethnic or religious majority. This held true for the mass expulsions of ethnic Germans from Poland after World War II, and the almost contemporaneous exodus of both Muslims and Hindus to Pakistan and India, respectively. Importantly, it also applied to the hundreds of thousands of Jewish refugees expelled from Arab and Muslim countries following the 1948 war, who were resettled in the new State of Israel.

Once the Arab and Palestinian position on return shifted from a fear of recognizing Israel to the idea of building a fifth column within the state to wage an indefinite war against Zionism, Wilf and Schwartz write, “The state of Israel … was being asked by the Arabs to perform an extraordinary act: it was called on to admit to its sovereign territory hundreds of thousands of Arabs, against international norms of the time, without a peace treaty, and while the Palestinians and the Arab world continued to threaten it with another war — even calling the refugees a pioneer force toward this end.”

Although anti-Zionists today insist that Israel’s refusal to accept a return of the refugees was a uniquely heinous violation of human rights and international law, it was entirely consistent with the moral and legal norms of the time.