In Quillette, Mark Andre Alexander recounts his first brush with “The Underground Grammarian”:

My first upper division English class shocked me when a dinosaur English professor, Dr. David Bell — a professor in Richard Mitchell’s mold, but not yet a curmudgeon — gave me my first C on a paper, busting my A-student self-image. That wake-up call helped me to see that, although I was published, I had much to learn about writing. Worse, in my first graduate course, Bell’s “Austen and Bronte,” I discovered that I had much to learn about reading, and that I lacked the acuity to appreciate Jane Austen’s clear, witty, and precise prose.

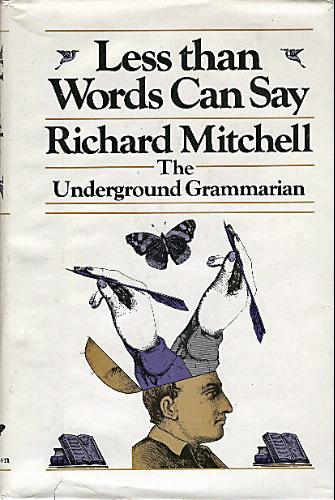

Not long before, I’d read Richard Mitchell’s first book, Less Than Words Can Say. I don’t recall how I stumbled upon him. I’d probably read some opinion column that referred to his work. In a publication announcement in the Underground Grammarian, Mitchell described it as “a melancholy meditation on the dismal consequences of the new illiteracy.”

He had wanted to title the book The Worm in the Brain, pointing to the dangers of administrative rhetoric. The publisher rejected that title as “too frightening and grisly,” But I knew I had found a fellow traveler when I read his Foreword:

Words never fail. We hear them, we read them; they enter into the mind and become part of us for as long as we shall live. Who speaks reason to his fellow men bestows it upon them. Who mouths inanity disorders thought for all who listen. There must be some minimum allowable dose of inanity beyond which the mind cannot remain reasonable. Irrationality, like buried chemical waste, sooner or later must seep into all the tissues of thought.

With that prophetic book, I first experienced the “cleansing fire [that] leaps from the writings of Richard Mitchell,” as George F. Will later described it.

Mitchell did title the first chapter “The Worm in the Brain,” in which he told the story of a colleague who would send him a note whenever there was some committee meeting. At first the note read something like, “Let’s meet next Monday at two o’clock, OK?” But when he aspired to become assistant dean pro tem, the simple, perfect prose changed. “This is to inform you that there will be a meeting next Monday at 2:00.” After achieving that appointment, the note read, “You are hereby informed that the committee on Memorial Plaques will meet on Monday at 2:00.” The worm in the brain had done its work.

I began to notice the worm in the brain during my everyday interactions with friends and colleagues at the university, especially the English professors. It often took the form of a label which created an image in the brain that prevented thought. One such professor, smart and engaging, returned a paper analyzing a passage in the U.S. Constitution. She gave the paper an A, but added, “I can’t help but feel that your argument is wrong, although I can’t explain why. I showed it to my husband, and he thought that it was a conservative argument.”

That statement invalidated the A, and I experienced my first taste of how subtly an abstract label can paralyze an otherwise thoughtful mind. Years later, while teaching at a business college, I saw a more pronounced form of the same phenomena. During a Business English class, I chatted with a bright student who volunteered for the NAACP. We would discuss all kinds of interesting topics, such as the similarities and differences between Martin Luther King and Malcolm X.

That is, until I noticed a change. She had stopped talking to me like a fellow human being and started talking at me like a white male. I stopped her and asked if she noticed what she had just done. She hadn’t, so I pointed out that she had shifted from talking to me to talking to an image inside her head. I told her that I would hold my hand up and block my face every time she did it. As the conversation proceeded, and I raised my hand, lowered it, and then raised it again, she became aware of the worm in her brain, a mental-emotional implant that prevented her from treating me as a colleague when certain topics were engaged.

Her implant was creating rubbish, of course, but it was insidious by nature because it disguised itself as something in the real world. Worms in the brain are like that.