The central problem of relations with de Gaulle stemmed from President Roosevelt’s distrust. Roosevelt saw him as a potential dictator. This view had been encouraged by Admiral Leahy, formerly his ambassador to Marshal Petain in Vichy, as well as several influential Frenchmen in Washington, including Jean Monnet, later seen as the founding father of European unity.

Roosevelt had become so repelled by French politics that in February he suggested changing the plans for the post-war Allied occupation zones in Germany. He wanted the United States to take the northern half of the country, so that it could be resupplied through Hamburg rather than through France. “As I understand it,” Churchill wrote in reply, “your proposal arises from an aversion to undertaking police work in France and a fear that this might involve the stationing of US Forces in France over a long period.”

Roosevelt, and to a lesser extent Churchill, refused to recognize the problems of what de Gaulle himself described as “an insurrectional government”. De Gaulle was not merely trying to assure his own position. He needed to keep the rival factions together to save France from chaos after the liberation, perhaps even civil war. But the lofty and awkward de Gaulle, often to the despair of his own supporters, seemed almost to take a perverse pleasure in biting the American and British hands which fed him. De Gaulle had a totally Franco-centric view of everything. This included a supreme disdain for inconvenient facts, especially anything which might undermine the glory of France. Only de Gaulle could have written a history of the French army and manage to make no mention of the Battle of Waterloo.

Anthony Beevor, D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, 2009.

June 5, 2014

QotD: Churchill, Roosevelt and de Gaulle

Silly anti-gaming columnist soundly rebuked by readers

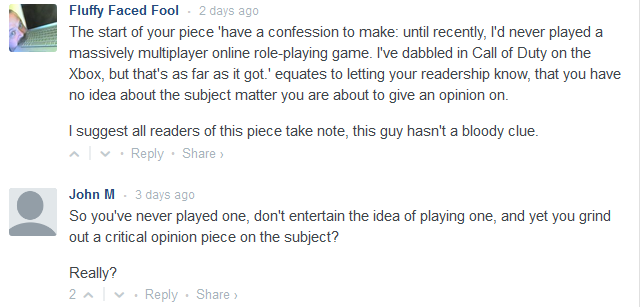

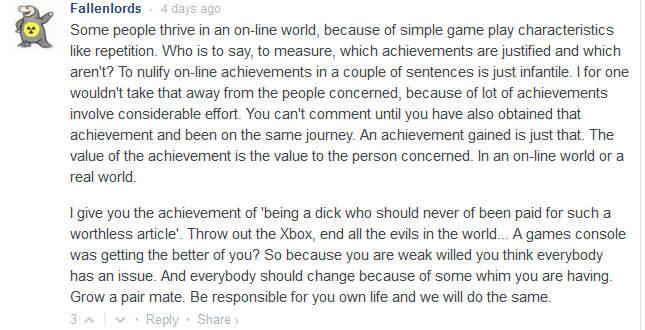

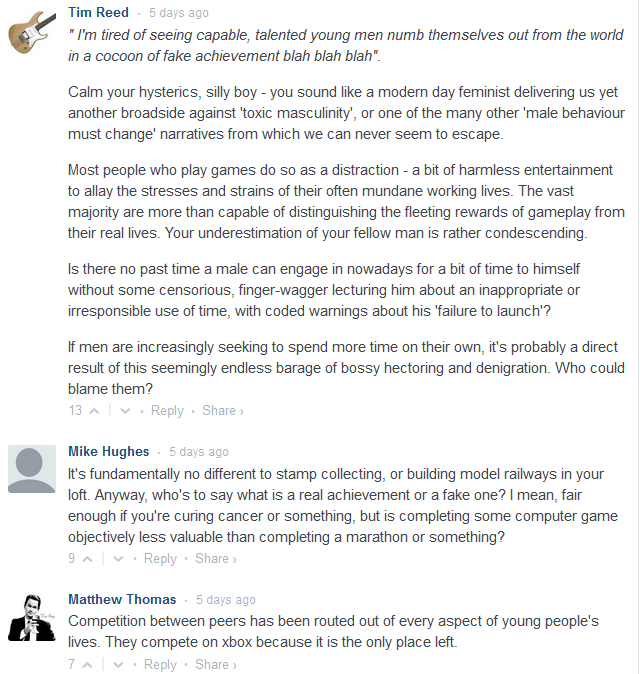

In the Telegraph last week, William Henderson first made it clear that “until recently, I’d never played a massively multiplayer online role-playing game. I’ve dabbled in Call of Duty on the Xbox, but that’s as far as it got.” Having gotten that out of the way, he then launched into a condemnation of the very games he admits he doesn’t play and has already explicitly admitted he knows very little about:

… I felt like Neo at the end of The Matrix when he sees the shimmering green code of the system, and finally realises the true nature of the prison for his mind.

I won’t name the game in question: there’s no need – so many of them feature similar ways of getting the gamer hooked. Is it cynical of me that I no longer view video games as a means of innocuous pleasure? Definitely. But that cynicism is entirely justified: it’s a reflection of the nature of video games today. As I’ve previously written about, games today tend to reward repetition rather than skill, and gone is the social element where guys would go round each other’s house and actually be in each other’s company. The more successful you want to be at video games nowadays, the more you need to be a hermit.

This is not to say that I begrudge gamers – everyone needs their downtime. However, the key word here is ‘success’. I’m tired of seeing capable, talented young men numb themselves out from the world in a cocoon of fake achievement. I’m tired of how their reward for completing utterly meaningless tasks is another load of worthless digital points – and more meaningless tasks. I’m tired of how the biological mechanisms which ensured their survival and evolutionary success are being hijacked to make them slaves to their own mind.

I rarely bother to read the comments on any site, but I was impressed with the quality of the comments here:

Conspiracy theorist’s festival day

Matt Welch on the last few decades that paved the way for a re-expansionist Russia:

On September 10, 1990, U.S. President George Bush and Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev issued a simple and remarkable joint statement. “We are united in the belief that Iraq’s aggression must not be tolerated,” the former Cold War opponents declared after a seven-hour meeting in Helsinki to discuss Saddam Hussein’s annexation of Kuwait. “No peaceful international order is possible if larger states can devour their smaller neighbors.”

Observers understood immediately the historical significance of two previously antagonistic superpowers agreeing on the principle that countries cannot swallow one another. What was less obvious at the time is that the moment would look like science fiction from the perspective of the future as well.

President Bush — we did not need to differentiate him as “H.W.” back then — was so giddy about the prospects of rules-based global cooperation that on the not-yet-portentous date of September 11, 1990, he gave an unfortunate name to the concept during an address to a joint session of Congress: new world order.

“Most countries share our concern for principle,” he asserted. “A new partnership of nations has begun, and we stand today at a unique and extraordinary moment. The crisis in the Persian Gulf, as grave as it is, also offers a rare opportunity to move toward an historic period of cooperation. Out of these troubled times, our fifth objective — a new world order — can emerge: a new era-freer from the threat of terror, stronger in the pursuit of justice and more secure in the quest for peace. An era in which the nations of the world, east and west, north and south, can prosper and live in harmony. […] A world where the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle. A world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice. A world where the strong respect the rights of the weak.”

Because “new world order” sounded creepy and was already a phrase used by conspiracists worried about one-world government, Bush’s larger point got washed away in the ensuing brouhaha. But terminology aside, the creation of an international taboo against subsuming weaker countries was a worthwhile endeavor.

Mother Jones on the Rothbard-Koch feud

I met Murray Rothbard a few years before he died, sharing a panel with him at a Libertarian event in Toronto. He was a fascinating, but uncomfortable man to talk with (at least on my brief acquaintance). He was an ideological fundamentalist and had no time for those who wanted to “water down” the libertarian message to make it more acceptable to the general public. In Mother Jones, Daniel Schulman reports on the bitter break between Charles Koch and Rothbard not long after the founding of the Cato Institute over exactly that kind of issue:

Long before Charles Koch became the left’s public enemy number one (or two, depending on where David Koch falls in the rankings), some of his most vocal detractors were not liberals but fellow libertarians. None of his erstwhile allies would come to loathe him more fiercely than Murray Rothbard, one of the movement’s intellectual forefathers, with whom Charles had worked closely to elevate libertarianism from a fringy cadre of radical thinkers to a genuine and growing mass movement.

In the 1970s, Charles helped fund Rothbard’s work, as the economist churned out treatise after treatise denouncing the tyranny of government. Rothbard was a man with a plan when it came to movement-building. Where some libertarians had bickered over whether to advance the cause through an academic or an activist approach, Rothbard argued that the solution wasn’t to choose one path, but both. Charles was taken with his strategic vision.

Rothbard dreamt of creating a libertarian think tank to bolster the movement’s intellectual capacity. Charles Koch made this a reality in 1977, when he co-founded the Cato Institute with Rothbard and Ed Crane, then the chairman of the national Libertarian Party. This was a high point for libertarianism, when a busy hive of libertarian organizing buzzed on San Francisco’s Montgomery Street, home to Cato and a handful of other ideological operations bankrolled by Charles Koch.

But the relationship between Cato’s co-founders soon soured.

Rothbard, who was feisty by nature, chafed under the regime of Crane and Koch — the libertarian movement’s primary financier at that time. His breaking point came during the 1980 election, when David Koch ran as the Libertarian Party’s vice presidential nominee. Rothbard and his supporters felt that, in a bid for national legitimacy, David Koch and his running mate, Ed Clark, had watered down the core tenets of libertarianism to make their philosophy more palatable to the masses. Americans today would consider their platform — which called for abolishing Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid and eliminating federal agencies including the EPA and the Department of Energy — a radical one. But to Rothbard and his circle, it wasn’t radical enough. For instance, the Clark-Koch ticket stopped short of calling for the outright repeal of the income tax. And Clark, to Rothbard’s horror, had even defined libertarianism as “low-tax liberalism” in a TV interview.

Following the 1980 election, in which the Clark-Koch campaign claimed a little over one percent of the popular vote, Rothbard did not hold back. He penned a scathing polemic titled “The Clark Campaign: Never Again,” in which he wrote that Ed Clark and David Koch had “sold their souls — ours, unfortunately, along with it — for a mess of pottage, and they didn’t even get the pottage.” Thanks in part to Rothbard’s rabble-rousing, factional feuds and recriminations splintered the libertarian movement just as it was gaining momentum. A few months after Rothbard’s diatribe, Charles Koch and Ed Crane tossed him out of the Cato Institute and voided his shares in the think tank (which was set up, under Kansas law, as a nonprofit corporation with stockholders), a rebuke that turned their libertarian brother-in-arms into a lifelong adversary.

The Rothbard-Koch split was only the biggest of a lot of factional in-fighting in the movement in those days. Even in the outermost fringes of the movement (in Canada, for example), we had lots of splinters-of-splinters micro-movements going on (which is why the Monty Python skit about the People’s Front of Judea, the Judean People’s Front and the Judean Popular People’s Front “Splitters!” rings so true for me). Some days, we made the Communists/Marxist-Leninists look like sane, sensible co-operative folks.

Living in a post-Snowden world, under the gaze of the Five Eyes

It’s been a year since the name Edward Snowden became known to the world, and it’s been a bumpy ride since then, as we found out that the tinfoil-hat-wearing anti-government conspiracy theorists were, if anything, under-estimating the actual level of organized, secret government surveillance. At The Register, Duncan Campbell takes us inside the “FIVE-EYED VAMPIRE SQUID of the internet”, the five-way intelligence-sharing partnership of US/UK/Canada/Australia/New Zealand:

One year after The Guardian opened up the trove of top secret American and British documents leaked by former National Security Agency (NSA) sysadmin Edward J Snowden, the world of data security and personal information safety has been turned on its head.

Everything about the safety of the internet as a common communication medium has been shown to be broken. As with the banking disasters of 2008, the crisis and damage created — not by Snowden and his helpers, but by the unregulated and unrestrained conduct the leaked documents have exposed — will last for years if not decades.

Compounding the problem is the covert network of subornment and control that agencies and collaborators working with the NSA are now revealed to have created in communications and computer security organisations and companies around the globe.

The NSA’s explicit objective is to weaken the security of the entire physical fabric of the net. One of its declared goals is to “shape the worldwide commercial cryptography market to make it more tractable to advanced cryptanalytic capabilities being developed by the NSA”, according to top secret documents provided by Snowden.

Profiling the global machinations of merchant bank Goldman Sachs in Rolling Stone in 2009, journalist Matt Taibbi famously characterized them as operating “everywhere … a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money”.

The NSA, with its English-speaking “Five Eyes” partners (the relevant agencies of the UK, USA, Australia, New Zealand and Canada) and a hitherto unknown secret network of corporate and government partners, has been revealed to be a similar creature. The Snowden documents chart communications funnels, taps, probes, “collection systems” and malware “implants” everywhere, jammed into data networks and tapped into cables or onto satellites.

A visual history of pin-up magazines

A review of a new three-volume history of the girly magazine:

Taschen delivers as only Taschen can with Dian Hanson’s History of Pin-Up Magazines, a comprehensive three-volume boxed set chronicling seven decades in over 832 munificently illustrated pages, tipping the scales at nearly seven hardbound pounds. Although each volume is ram-packed with a bevy of sepia sweethearts, hand-tinted honeys, and Kodachrome cuties squeezed between dozens of lurid full-page vintage magazine covers, the accompanying text is so compelling that you’re apt to actually read these books too. And there’s a lot to learn about the history of pin-up magazines, more than you’d ever imagine, and this set leaves no stone unturned and no skirt unlifted. From the suggestive early illustrations of the post-Victorian era to the first bare breasts, the intriguing sources that fueled the fires of popular fetish trends, and the many ways in which publishers tried to legitimize the viewing of nude women while gingerly dancing around obscenity laws, we watch this breed of pulp morph and reinvent with fiction or humor, and later the marriage of crime and flesh. We see the influence on pin-up culture in the wake of the First World War and with the advent of World War II and the rise of patriotica. We follow the path of the bifurcated girl, to eugenics, the role of burlesque, and the legalization of pubic hair. We venture under-the-counter, witness the death of the digest and the pairing of highbrow literature and airbrushed beauties. Hanson even treats us to a peek into the lesser-known black men’s magazine genre, and the contributions made by erotic fiction and Hollywood movie studios.