Safetyism is a disposition that has been gaining strength for decades and is having a triumphal moment just now because of the virus. Public health, one of many institutions that speak on behalf of safety, has claimed authority to sweep aside whole domains of human activity as reckless, and therefore illegitimate.

I suspect the ease with which we have lately accepted the authority of health experts to reshape the contours of our common life is due to the fact that safetyism has largely displaced other moral sensibilities that might offer some resistance. At the level of sentiment, there appears to be a feedback loop wherein the safer we become, the more intolerable any remaining risk appears. At the level of bureaucratic grasping, we can note that emergency powers are seldom relinquished once the emergency has passed. Together, these dynamics make up a kind of ratchet mechanism that moves in only one direction, tightening against the human spirit.

Acquiescence in this appears to be most prevalent among the meritocrats who staff the managerial layer of society. Deferring to expert authority is a habit inculcated in the “knowledge economy”, naturally enough; the basic currency of this economy is epistemic prestige.

Among those who work in the economy of things, on the other hand, you see greater skepticism toward experts (whether they make their claim on epistemic or moral grounds) and less readiness to accept the adjustment of social norms by fiat – whether that means using new pronouns or wearing surgical masks. I am regularly in welding supply stores, auto parts stores and other light-industry venues. Nobody is wearing masks in these places. They are very small businesses: an environment largely free of the moral fashions and corresponding knowledge claims that set the tone in large organisations. There is no HR in a welding shop.

A pandemic is a deadly serious business. But we would do well to remember that bureaucracies have their own interests, quite apart from the public interest that is their official brief and warrant. They are very much in the business of tending and feeding the narratives that justify their existence. Further, given the way bureaucracies must compete for funding from the legislature, each must make a maximal case for the urgency of its mission, hence the necessity of its expansion, like a shark that must keep moving or die. It is clearer now than it was a few months ago that this imperative of expansion puts government authority in symbiosis with the morality of safetyism, which similarly admits no limit to its expanding imperium. The result is a moral-epistemic apparatus in which experts are to rule over citizens conceived as fragile incompetents.

But what if this apparatus were revealed to be not very serious about safety, the very ideal that underwrites its authority? What then?

May 18, 2020

Safetyism

May 17, 2020

China sees their public image damaged in the wake of the Wuhan Coronavirus

Arthur Chrenkoff on the ways other countries regard China after the epidemic spread beyond their borders and the Chinese Communist Party’s antics on the world stage:

Welcome to the political chaos theory – or, should we say, fact: a bat flapping its wings in China produces a hurricane… pretty much everywhere around the world. It seems likely that three decades’ worth of good PR painstakingly build up by the Chinese authorities after the downer of the Tiananmien Massacre have all been undone in a few short months of domestic and international missteps, from initially covering up the truth about COVID, through gifting or selling faulty personal safety and medical goods around the world, to now retaliating against countries like Australia which are asking some uncomfortable questions about the origins of the virus.

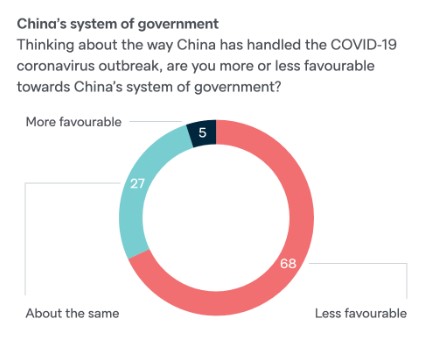

Earlier today, Australia’s Lowy Institute has released the results of its COVID poll on public attitudes about the Corona pandemic. Of particular interest, the perception of China’s rulers:

At the same time, 37 per cent of Australians think that China will emerge more powerful after the dust (or the viral load) settles, while 36 per cent believe in no change, and only 27 per cent think China will be weaker in the aftermath. By contrast, a majority of 53 per cent and a plurality of 48 per cent believe that the United States and Europe respectively will be less powerful in the post-pandemic future. Reading the two sets of figures together it seems that the prospect of China’s rebound to international power is viewed more with apprehension rather than enthusiasm.

As Lowy’s Natasha Kassam observed, the public trust in China has been already declining, falling dramatically from 52 to 32 per cent in just one year between 2018 and 2019. It will be interesting to see the figure for this year. It’s unlikely that the behaviour of the communist government so far in 2020 would have improved the perception.

Such findings mirror similar public opinion research elsewhere. Pew Research Center’s polling last month showed that the negative view of China in the United States has risen from 47 per cent in 2017 to 66 per cent this year. Seventy-one per cent have no confidence in China’s President for Life Xi and 61 per cent view China’s power and influence as a major threat.

May 16, 2020

Remy: “Surfin’ USA” (Beach Boys Lockdown Parody)

ReasonTV

Published 15 May 2020Remy discovers the dangers of exercising alone.

Written and performed by Remy. Music tracks, mastering, and background vocals by Ben Karlstrom. Video produced by Meredith and Austin Bragg.

LYRICS:

If you go out on the ocean

Across the USA

And you’re wearing a swim shirt

‘Cuz of your scrawny weight (it’s for the sun, I swear)Well, uh, you just might notice

The police in your wake

Cuz it’s illegal to be surfing

In the USAThey’re catching them out paddle boarding

Letting their children play

While they’re releasing this guy

A logical checkmateYou’re out in nature alone now

No one in six-foot range?

Well it’s illegal to be surfing

In the USAIf only you had flashed some children

It’d be your release date!

But you’re going to jail for surfing

In the USAYou’ve been distancing for months now

To keep the spread rate down

The only places you’ve been going

Are where there are no crowdsYou’re making sacrifices

For your community

Now put your hands on your head because you are surfing

In the USAHe’s helping the flattening the curve now

He’s exercising alone

Rocking a super baggy swim shirt

To hide his muscle tone (I said it’s for the sun)If only you had flashed some children

It’d be your release date!

But you’re going to jail for surfing

In the USA

The Wuhan Coronavirus, the excuse for an emergency without end

Mark Steyn on the seven-hundred-and-fifty-third day of our captivity:

Emergency without end is the staple of almost every futuristic dystopia — and that’s true for real life, too. So Americans shuffle shoeless through the airports for twenty years while their governments negotiate with the very organization that enabled those attacks — the Taliban — to restore them to power. Is a culture that cannot see off goatherds with fertilizer really going to rouse itself to decouple from a global superpower that supplies everything from its crappy “These Colors Don’t Run” T-shirts to its surgical masks and pharmacy medications?

~For my own part, I have been reading ancient accounts from Occupied France and Vichy for tips on finding workarounds for restraints on the citizenry. As wily and innovative as the French Resistance were, I wonder if their efforts would even be possible in an age when cheap Chinese-made drones can hover unseen and monitor every conversation.

[…]

Even without governors terrorizing those tavern-keepers or hairdressers who defy them, the lockdown has exaggerated the contradictions: The state wants open borders for “migrants” but a security perimeter around the homes of its citizens. Maybe the absurdities become so obvious that there is widespread rejection of them. Or maybe, one by one, the poor put-upon over-surveilled citizenry take a cue from their undocumented non-brethren. Perhaps I should just mug an illegal immigrant and steal his fake ID…

~The emergency is already feeling permanent. It starts with the social norms: Dr Fauci tells us the handshake is gone for good. That’s not a small loss. I don’t care for the suggested replacements, like the lame-o hand-on-heart gesture. I bow from the neck to the Queen — and just last year I did so to her Canadian vicereine, Mme Payette. Her Excellency then stepped forward and gave me a hug. But I don’t suppose she’s doing that anymore…

People ask me why I haven’t been on TV lately. Well, I mainly like going on TV to behave like a person who’s on TV. So, if you notice, on the “Fox & Friends” live-audience shows, I come bounding in like Tigger and do a lot of gladhanding with those on the aisle (including the odd hug), and then I give Steve and Brian manly handshakes and do a little light kissy-kissy with Ainsley. And all that — the basic language of telly for seventy years — is gone, apparently forever.

[…]

The WHO, the Beijing public relations firm whose pronouncements the BBC, The New York Times et al insist on taking as gospel, now says Covid-19 is here to stay — like HIV. With HIV, it wasn’t that difficult to avoid catching it, because it required the exchange of bodily fluids, which is a fairly intense and specific degree of intimacy. With Covid, we are rolling a protective condom down over every routine social intercourse.

A contributor at the Continental Telegraph explains why he no longer supports the lockdown:

First, it turns out that the drastic steps we were taking were based on one model. That no one outside the team using it was allowed to review. We were even told that we couldn’t check the coding because it was so old & patched together that it’s too hard to follow. That’s like saying you can’t check the brakes because you won’t be able to see all the duct tape and Velcro we’re using. Further, we’re told that this software doesn’t provide the same results from one run to the next.

Next, I heard about Dr. Ferguson’s history of wildly overestimating the fatalities from mad cow disease and bird flu (50k compared to <200, 200 million versus <500 respectively). Also, the CDC’s estimate of Ebola deaths in Sierra Leone (1.4 million compared to 8k). And let’s not forget the U.S. Public Health Service’s overshoot on the number of AIDS infections in 1993 (450k versus 17k). At this point I gave more thought to the issue of modeling – prior to retiring I was an actuary and modeling was what I did for a living. A few points about how modeling works: The more complex a system is, the more difficult it is to build a good model. And, more importantly, the more difficult it becomes to test your model and confirm that it accurately mirrors the real world. And this looks like one of the most complex systems to model I’ve ever heard of. How can you test this against reality? I don’t think you can. You can run simulations and confirm it looks like you expected, but that doesn’t mean the virus behaves like your model. Another point about modeling is that the results are extremely dependent on the assumptions you’re using. And in this case two critical assumptions are how infectious the virus is and how lethal it is. We still have a poor understanding of these variables months after we started Lockdown. Then a lot of us noticed that the goal shifted from “flattening the curve” to avoid a catastrophic overflow at hospitals to Lockdown until “fill in the blank” (in some states a vaccine, in others no deaths for 14 days, etc.). And the lockdown rules are inconsistent and illogical – in Michigan you can’t buy plant seeds but you can buy lottery tickets. To add insult to injury, many of the people with their foot on our necks violate the rules (the mayors of Chicago and New York, Dr. Ferguson, etc.). I’m stunned and angry at how little attention the human costs of the Lockdown receive. We know that this will lead to increased suicides, homicides and drug overdoses. Let’s not forget more child abuse, domestic violence, depression, drug and alcohol abuse, the list of miseries goes on a very, very long way (I may write up an article just on this, the Lockdown harpies should have to admit to all the harm they’re so enthusiastically spreading).

May 15, 2020

Wuhan Coronavirus muzzles mandated by “politicians who are completely-fall-down-drunk on Chateau d’House Arrest”

Laura Rosen Cohen at Steyn Online:

Hello again, and welcome to week eleventy billion gazillion of CCP-Style Lockdown in the Allegedly Free World.

Another week of hypocrisy from the politicians who are completely-fall-down-drunk on Chateau d’House Arrest.

And another week of me feeling like I look rather like this penguin when attempting to articulate how disgusted I am with the governments of western countries – my own country and province in particular.

I don’t want any more “we’re all in this together” e-mails. I don’t want to hear “Covid-19” uttered in a morose, yet sadistically gleeful, tone with odd, demonic-like smiles. I don’t want to see any more playgrounds taped up. I don’t want to see any more “Stay Home” notices. And I most certainly will refuse the “new normal” being offered to us by the power-drunk politicians and nanny-craving, safe space lunatic multitudes.

I was talking to my wonderful and brilliant partner-in-crime Kathy Shaidle about why we hate masks. (Oh go on, just admit it, you hate them as well). First of all, like with the WuFlu, we have no exact science about them, and the reasons for wearing or not wearing keep changing, just like the reasons for continued lockdown. For a while now, I’ve been looking at them as a kind of pandemic virtue signalling device. Like a Health & Safety Boy Scout badge. But I couldn’t articulate exactly what else was bothering me about them. She sent me this:

Testing is futile. It could never be extensive or fast enough to find out anything useful in time. Compulsory muzzles, symbolic of subjection, loss of identity and muteness, are indeed oppressive. https://t.co/w84bWTApuv

— Peter Hitchens (@ClarkeMicah) May 10, 2020

and said ‘leave it to a Hitchens to articulate it’. Bingo.

I replied to my dear Kathy that they are indeed like a burkah, something that anonymizes you and that renders normal civil discourse and interaction, like smiles, conversation and flirtation impossible. She added that they are also a kind of affront, a dare to others who you imply are inferior for not wearing yours. Then I saw this: indeed it is, the Corona Niqab. Nuts to that. And if you think I’m pissed, I urge you to listen to this interview with novelist Lionel Shriver who puts it better than I ever could. Shriver delivers the outstanding righteous fury we need to hear, a level of outrage matched and raised to a new level each day by my gracious and prophetic host himself.

May 12, 2020

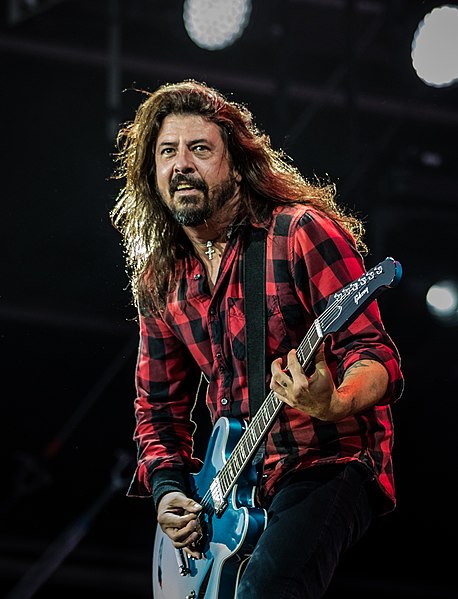

Dave Grohl on live music

Writing in The Atlantic, he regrets having to miss a particular event:

Dave Grohl and the Foo Fighters at Rock am Ring, 3 June 2018.

Photo by Andreas Lawen via Wikimedia Commons.

Where were you planning to be on the Fourth of July this year? Backyard barbecue with your crankiest relatives, fighting over who gets to light the illegal fireworks that your derelict cousin smuggled in from South Carolina? Or maybe out on the Chesapeake Bay, arguing about the amount of mayonnaise in the crab cakes while drinking warm National Bohemian beer? Better yet, tubing down the Shenandoah with a soggy hot dog while blasting Grand Funk Railroad’s “We’re an American Band”?

I know exactly where I was supposed to be: FedExField, outside Washington, D.C., with my band Foo Fighters and roughly 80,000 of our closest friends. We were going to be celebrating the 25th anniversary of our debut album. A red, white, and blue keg party for the ages, it was primed to be an explosive affair shared by throngs of my sunburned hometown brothers and sisters, singing along to more than a quarter century of Foo.

Well, things have changed.

Unfortunately, the coronavirus pandemic has reduced today’s live music to unflattering little windows that look like doorbell security footage and sound like Neil Armstrong’s distorted transmissions from the moon, so stuttered and compressed. It’s enough to make Max Headroom seem lifelike. Don’t get me wrong, I can deal with the monotony and limited cuisine of quarantine (my lasagna game is on point!), and I know that those of us who don’t have to work in hospitals or deliver packages are the lucky ones, but still, I’m hungry for a big old plate of sweaty, ear-shredding, live rock and roll, ASAP. The kind that makes your heart race, your body move, and your soul stir with passion.

There is nothing like the energy and atmosphere of live music. It is the most life-affirming experience, to see your favorite performer onstage, in the flesh, rather than as a one-dimensional image glowing in your lap as you spiral down a midnight YouTube wormhole. Even our most beloved superheroes become human in person. Imagine being at Wembley Stadium in 1985 as Freddie Mercury walked onstage for the Live Aid benefit concert. Forever regarded as one of the most triumphant live performances of all time (clocking in at a mere 22 minutes) Freddie and Queen somehow managed to remind us that behind every rock god is someone who puts on their studded arm bracelet, absurdly tight white tank, and stonewashed jeans one pant leg at a time just like the rest of us. But, it wasn’t necessarily Queen’s musical magic that made history that day. It was Freddie’s connection with the audience that transformed that dilapidated soccer stadium into a sonic cathedral. In broad daylight, he majestically made 72,000 people his instrument, joining them in harmonious unison.

May 10, 2020

London’s Metropolitan Police live down to expectations … and then some

Brendan O’Neill observes the latest sweep by the Metropolitan Police, relentlessly cracking down on scofflaws and evil-doers who … were walking peacefully in the sunshine?

Armed Metropolitan Police near Downing Street in London.

Photo by Stanislav Kozlovskiy via Wikimedia Commons.

You heard them before you saw them. It sounded like a platoon of soldiers. The one in charge was barking orders to “move forward!” and then came the trudge of their boots. Scores of them, making military manoeuvres, marching in a long, thin line through one of Britain’s prettiest parks: St James’s Park in London. This was the Metropolitan Police today, enforcing the lockdown, sweeping through parks and streets and issuing the same warning to everyone they came across, from young lovers to dads playing football with their kids to homeless people with nowhere else to go: “Move on.” It’s one of the most disturbing things I’ve ever seen the police do.

Watching them stream through St James’s Park, looking for all the world like a line of soldiers conquering a small town, you’d think they were on their way to confront some serious organised crime. But of course their targets were sunbathers, those apparently selfish people demeaned in the media and now harassed by the cops. And a dad playing football with his toddler. “Aren’t we allowed to exercise?”, the dad asked. “For one hour”, came the reply. “How long have you been out?” And young lovers and friends. I saw a copper on horseback shouting down at two young men as if they were in the process of committing some awful crime. I guess they were in the eyes of the lockdown fanatics: they were sitting under a tree.

A young Muslim mum sitting down and watching her two kids play with little tennis bats was confused, too. Can’t kids play outside? She was told she couldn’t sit still. She had to walk. “How about walking your kids around the park?”, said the spectacularly patronising cop. They even threw out homeless people. I saw them tell four individual homeless people (ie, not a group of homeless people) to move on. Where to? Must they also walk and walk, forever, and never sit down anywhere? The most despicable thing I saw was a policeman telling an elderly homeless gentleman to move on. Inarticulately, the man explained he had nowhere else to go. I stepped in and explained to the cop that there is no home for him to go to, and he has to be able to sit down somewhere on a hot day. “I don’t make the rules”, came the snivelling, officious reply.

The police’s reputation will have taken a severe beating in London today. Anyone who argued back — as two young women did, patiently explaining that they are from the same household and that they were metres away from everyone else — was patronised or even insulted. “You’re putting other people’s lives at risk”, the women were told, which is completely untrue — being outside and socially distanced on a very warm day carries virtually zero threat of infection. I heard an officer call someone an idiot. Another officer made fun of someone who asked about his right to be outside. It was staggeringly rude and even repugnant behaviour. A politician, or someone, needs to get a grip on these people.

May 8, 2020

The Wuhan Coronavirus lockdown – “perhaps the worst policy mistake ever committed by Western governments during peacetime”

Toby Young on the fall of “Professor Lockdown”, the former top advisor to the British government on the response to the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic:

The reason for looking into the political affiliations of the scientists and experts who’ve been advising governments across the world during this crisis is that it may throw some light on why those governments have made such poor policy decisions. Will the vast majority of those advisers turn out to be left-of-centre, like Professor Ferguson? I’m 99% sure of it, and I think that will help us to understand what’s happened.

I don’t mean they’ve deliberately given right-of-centre governments poor advice in the hope of wrecking their economies for nefarious party political reasons or because they’re members of Extinction Rebellion and want to destroy capitalism. Nor do I believe in any of the conspiracy theories linking these public health panjandrums to Bill Gates and Big Pharma and some diabolical plan to vaccinate 7.8 billion people. I have little doubt they’ve acted in good faith throughout – and that’s part of the problem. The road they’ve led us down has been paved with all the usual good intentions.

The mistakes these liberal policy-makers have made are depressingly familiar to anyone who’s studied the breed: overestimating the ability of the state to solve complicated problems as well as the capacity of state-run agencies to deliver on those solutions; failing to anticipate the unintended consequences of large-scale state interventions; thinking about public policy in terms of moral absolutes rather than trade-offs; chronic fiscal incontinence, with zero inhibitions about adding to the national debt; not trusting in the common sense of ordinary people and believing the only way to get them to avoid risky behaviour is to put strict rules in place and threaten them with fines or imprisonment if they disobey them (and ignoring those rules themselves, obviously); arrogantly assuming that anyone who challenges their policy preferences is either ignorant or evil; never venturing outside their metropolitan echo chambers; citizens of anywhere rather than somewhere… you know the rest. We’ve seen it a hundred times before.

More often than not, the “solutions” these left-leaning experts come up with make the problems they’re grappling with even worse, and so it will prove to be in this case. The evidence mounts on a daily basis that locking down whole populations in the hope of “flattening the curve” was a catastrophic error, perhaps the worst policy mistake ever committed by Western governments during peacetime. Just yesterday we learnt that the lockdowns have forced countries across the world to shut down TB treatment programmes which, over the next five years, could lead to 6.3 million additional cases of TB and 1.4 million deaths. There are so many stories like this it’s impossible to keep track. We will soon be able to say with something approaching certainty that the cure has been worse than the disease.

May 7, 2020

Interesting change in shipping patterns … to avoid the Suez canal

Colby Cosh linked to this story at gcaptain.com which would have been an unbelievable one in the pre-epidemic world:

A column of ships along the Suez Canal on 3 December, 2011.

Photo by https://web.archive.org/web/20161022104657/http://www.panoramio.com/user/2433337?with_photo_id=64163879 via Wikimedia Commons.

The Suez Canal Authority (SCA) is set to lose over $10m in revenue from container lines routing vessels via the Cape of Good Hope rather than its waterway.

According to new Alphaliner research, “the number of containerships that have opted to use the Cape route and bypass the Suez Canal has risen to a historic peace-time high,” including at least 20 sailings on the Asia-Europe, Europe-Asia and North America east coast-Asia trades.

“A unique combination of a container tonnage surplus and rock-bottom bunker prices has increasingly prompted ocean carriers to avoid the canal – and thus its fees,” the analyst noted today.

“Rather unusually, even three westbound Asia-Europe headhaul sailings have opted for the Cape route, all operated by CMA CGM.

“Carriers very rarely choose this longer route for the time-sensitive headhaul, but the low bunker price and lack of demand in European markets, hit by the Covid-19 lockdowns, have suddenly made such moves viable,” it added.

“When it’s over we can shave the heads of a few easy victims and vilify a few who enjoyed it too much. But I collaborated too.”

The mandatory shutdown of most of the world’s economy is inducing some introspection:

Prime Minister Boris Johnson at his first Cabinet meeting in Downing Street, 25 July 2019.

Official photograph via Wikimedia Commons.

I looked again at the decisions of the Johnson government. Should they have followed my instincts? No lockdown. Shield the elderly and the vulnerable, like my elder daughters immuno-deficient boyfriend, but let all normal life continue. Let the virus rip. Let the football league play out its conclusion and more to the point let out beloved Dundee Stars Elite Ice Hockey Club break our hearts and miss the playoffs. Such a government would probably have fallen within days, battered by the broadcast media, backbench rebellion and a nation that preferred to be kept safe from the unknown that they feared. Had they survived the month, then the elderly who by choice refused to be shielded would have pitched up in their thousands at A&E, to be faced with experienced nurses like my wife who triaged them on the doorstep and sent many of them home to die, to preserve the ICU beds for those who could be saved. Instead of admitting them so that they could die with every bit as much certainty. Had he survived the first month, Johnson would have fallen regardless and nation would be traumatised by the memory of grandparents sent home to die

Had I been in his shoes, I too would have sued for peace. My nation demanded it of me. I would have convinced myself it was the right thing and when the chest pain and cough arrived, I would have felt relief that I had made the correct call. I would have looked at the Malice of Piers Morgan and convinced myself that I was still moderate. I would have dismissed the feeble objections of lunatic libertarians.

When it’s over we can shave the heads of a few easy victims and vilify a few who enjoyed it too much. But I collaborated too.

May 6, 2020

Essential private sector workers and non-essential government workers

A couple of articles at the Foundation for Economic Education look at the arbitrary division of peoples’ jobs into two broad categories:

In a recent TV appearance with Dana Perino on The Daily Briefing, [Mike] Rowe made it clear he’s not a fan of the terms “essential” and “non-essential” worker. The problem with such a view, Rowe said, is that such terms have little actual meaning and the economy makes no such distinction.

“There’s something tricky with the language going on here, because with regard to an economy, I don’t think there is any such thing as a nonessential worker,” Rowe said. “This is basically a quilt … and if you start pulling on jobs and tugging on careers over here and over there, the whole thing will bunch up in a weird way.”

Rowe’s message is precisely what FEE president and economist Zilvinas Silenas was getting at in a recent article published at Townhall.

Allowing politicians to decide which businesses and products are “essential” is an invitation for disaster. If we continue to deny these businesses the ability to do the one essential thing they are best at — providing goods and services to millions of everyday Americans — we risk more than unemployment or recession of stock price plunge. We deprive ourselves of the best resource — our people — during the time of need.

The truth is, all workers are essential.

Unfortunately, all too often what is deemed “essential” is simply what’s convenient to state leaders making the decisions. Few would suggest that liquor store owners are inherently more essential than pizza parlor owners — except perhaps state revenue collectors. No doubt this is the same reason Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer concluded that lottery tickets are essential, but gardening seeds are not.

Liquor stores and lottery tickets aren’t especially “essential” to Americans, just state budgets. But as one Washington State sheriff noted in April, this seems to be the criteria state leaders often use to determine what is “essential” and “non-essential”: whether it helps the government’s bottom line.

When the state picks winners and losers it’s not only unfair, however. It’s also destructive.

In the other piece, J. Kyle deVries points out that government cannot be immunized from the economic harm the shutdown has and continues to inflict on the private sector:

So far millions in the private sector have lost their jobs or have been furloughed — but not many in government have. Many government employees continue to get salaries and benefits despite not working. Their agencies most certainly will not have as much work to do since major portions of the economy are closing down. Many agencies won’t even be needed any longer, but you better believe they will continue to be funded and probably expanded over time. That is outrageous. As we suffer economically, government should not be exempted.

This phenomenon is truly confounding and unfair. After all, government does not exist without taxes and taxes can only come from people who produce and earn a living — in other words, the private sector. The private sector supports government employees who, on average, receive higher pay, better perquisites and much better retirement plans. That should change. As we restructure our economy in the wake of the coronavirus, government should be restructured as well.

Businesses have no guarantee they will remain in business — they must provide their customers with a quality product or service at a competitive price or they will go bust. But government agencies remain in place for life, even if they continue to provide lousy services at outrageous expense. Government needs to show us they are with us during this fight. Part of doing so is to take a hard look at various agencies and departments to see if they can be improved or if they need to be eliminated. Before you say that would be difficult, let’s look at some obvious choices.

May 5, 2020

The perverse incentives of the Wuhan Coronavirus outbreak

David Warren has clearly taken his cynical pills today:

The daily count of deaths from the Red Chinese Batflu is among the prized, scare-mongering features of our mass media. I am among those who consider these numbers to be significantly overstated, for a reason that Nikolai Gogol would understand. Each corpse is worth cash to some public authority, usually from a higher authority; and as always, finally from the taxpayers. Each also saves money for government programmes, that can be reallocated to the purchase of new votes. As the corpse providers from this virus are very old, and suffering from other life-threatening conditions, in almost every case, this statistical inflation is easy to perform. Death certificates are issued for any who died with “Covid-19,” whether or not they died from it, and more are then added of those who were never tested. Anything respiratory will do. It’s all judgement calls — on which side of the bread is buttered.

Compare if you will the Hong Kong Flu of 1968 and 1969. I was just reading a memoir, from down that memory hole. The death toll was actually higher then, than ours is now, and from within a smaller population; the victims included children and the young. Yet there were no interruptions in economic life; no public emergency theatricals; and at the height of the second wave of that scourge, we had events like Woodstock. (Those were the days, my friend.)

A neat way to correct for all our “judgement calls” might be to look at overall death rates, and see if they have risen or fallen. It is too early to get a clear view, but soon it may be too late, for vested interests will have tampered with them. All my life I have been learning to trust statistics, less — especially from those who dress in labcoats and affect that earnest look. Sometimes an exception must be considered, however. An unpredictable minority may be honest; some others might get numbers right by mistake.

May 4, 2020

Government “problem solving” is an oxymoron

Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan explain why you should back away quickly when you hear a variant of “We’re from the government and we’re here to help”:

A central theme of our recent book, Cooperation & Coercion, is that all governments are hamstrung when they attempt to fix problems. Policymakers suffer from the knowledge problem: they don’t know enough to foresee every eventuality that will follow from what they do. Politicians see a problem, speak in sweeping statements, then declare what will happen, assuming their edicts will settle matters. But that is always just the beginning. More often than not, all manner of unintended consequences emerge, often making things worse than they were before their policies went into effect.

Consider the United States’ three high-profile wars against common nouns over the past half-century. Lyndon Johnson declared a War on Poverty in the 1960s, Richard Nixon a War on Drugs in the 1970s, and George W. Bush declared a War on Terror in the early 2000s.

How are those wars working out? Because a back-of-the-envelope calculation indicates that we have spent somewhere in the neighborhood of $23 trillion in our attempt to eradicate poverty, drugs, and terror. Not only have we not won any of these wars, it is unclear that any of them can be won. These three so-called wars have managed to saddle future generations of taxpayers with unprecedented debt. And, as is the case with all coercive endeavors, policymakers ask us to imagine how bad things would have been had we not spent the trillions we did spend. And then they ask for even more money. So now we have unwinnable wars along with institutionalized boondoggles to support them.

We see the same sort of thing happening now in the face of the COVID-19 threat that has induced the largest panic attack in world history. In the name of safety, policymakers have shut down myriad productive endeavors. And there will be a raft of unintended consequences to follow. We are already seeing them manifest, and they portend potential disaster as supply chains fail.

The first cracks in US supply chains appeared in the meat industry. Smithfield Foods, reacting to a number of workers contracting the virus, shut down its Sioux Fall plant. Kenneth M. Sullivan, President and CEO, explained in a press release that, “the closure of this facility, combined with a growing list of other protein plants that have shuttered across our industry, is pushing our country perilously close to the edge in terms of our meat supply.” But it’s not just the meat plant that’s implicated. It’s everyone from the cattle farmer to the person who cooks dinner, and there are a number of people who have a place in that process who might first escape attention. The people who make packing materials needed to ship food, the maintenance workers who service machines up and down the supply chain, the truck drivers who move product from one place to another, the grocers who sell the product, the daycare workers who care for the grocers’ children so the grocers can work, and many, many more are all at risk.

[…]

In declaring some jobs “necessary” and others not, in focusing on one supply chain versus another, policymakers show how little they know about the nation’s economy. In their view, they can simply declare things they want to happen, and then those things will happen. But that is not how economies work. An economy is the sum total of everyone’s activities, and when the government declares that something must happen, all kinds of other things happen too.

Consider how all the “non-essential workers” have been sent home for the past two months. Who gets to declare which workers are non-essential to the economy, and by what standard? Most assumed that politicians had the correct answers to these questions. But, as we are discovering, there is no such thing as “non-essential” workers. All workers are essential. How do we know? Because their jobs existed. Profit-driven businesses do not create non-essential jobs. Those people’s jobs were essential to their employers. Further, those people’s jobs were incredibly essential to the people themselves. They need their wages to pay the rent, buy their food, make their car payments, and for everything else that makes their lives livable.

But policymakers simply declared them non-essential, as if there would be no fallout from that decision.

May 2, 2020

Drawing some conclusions from our Wuhan Coronavirus experiences

At Catallaxy Files, Justinian the Great provides an expanded list of nine lessons we should learn from our still ongoing Wuhan Coronavirus (aka “Chinese Batflu”, “Kung Flu”, “Bat-biter Bronchitis” and other names our betters insist we not use):

1. Models are not infallible.

When dealing with complex subject matter involving lots of uncertainties, unknowns and data gaps, modelling will almost certainly be wrong. That doesn’t make them worthless but nor does it mean they should be elevated to infallible status and acted upon as though they constitute proof of something.

If we can’t get epidemiological models right involving trajectories of months what is the chance of climate models being correct considering they involve substantially greater uncertainty, unknowns and data problems involving trajectories of decades to centuries?

[…]

2. Experts can get it wrong.

The pandemic has shown that epidemiologists and health experts the world over have got COVID-19 wrong at one stage or another.

The most famous example is the Imperial College model that forecast 2.2m deaths in the United States and over 500,000 deaths in the UK. Critics have argued this was never plausible but it was the catalyst for UK lockdown policy.

[…]

3. Experts can disagree

Experts can disagree and this is normal in science (and policy making).

During the pandemic, health experts across the world have disagreed over epidemiology models (e.g. R0) ranging from thousands of deaths to millions, over treatments (i.e. the efficacy of anti-virals and anti-malarials), over who and how to test (targeted (symptomatic) versus broad based (even antibody testing), how to record cases and fatalities (e.g. Italy counting deaths with COVID the same as due to COVID, Belgium recording deaths suspected to be COVID related but not verified), the origin and nature of the virus (laboratory/synthetic or wet market/natural), over what the public health response should be (full lockdowns, targeted lockdowns, Sweden (minimal) or something in-between), and the susceptibility of children to the virus, leading to divergence on school closures.

[…]

4. The Precautionary Principle – No such thing as a free lunch

The COVID-19 crisis is a classic case of the precautionary principle in action. The policy measures put in place have been justified by the worse case scenarios of epidemic models forecasting mass deaths and hospital systems in collapse. These scenarios have been hyped up by an alarmist media presenting such scenarios / predictions as established fact.

Part of the problem stems from politicians abdicating responsibility for decision-making and hiding behind health experts as human shields. These experts have nothing to gain and everything to lose from underestimating the epidemic. No-one wants to be blamed for hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths.

[…]

5. If you can’t trust the WHO in a pandemic why would you trust the IPCC on climate change?

The neo-liberal (in international relations terms) notion that the UN (and other international institutions) are independent actors working altruistically for the global good has been blown to bits during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The conduct of the WHO and its complicity with China throughout the pandemic has demonstrated what realists have always known, i.e. international institutions are not independent actors, but instead reflect the interests of great powers in the international system.

[…]

6. If you can’t trust the Chinese in a pandemic how can you trust them on climate?

The COVID crisis also demonstrates why should not trust a communist dictatorship to act truthfully, transparently or ethically, much less put global interests above national interests even in times of an international crisis.

If we can’t believe China about infection rates, how can we believe their carbon accounting? If we can’t trust China to reduce the spread of a virus, how can we trust China to reduce the growth in CO2 emissions? If we believe China has captured/corrupted the WHO how do we know it hasn’t captured/corrupted the IPCC? If China will prioritise national interest in a health crisis, why won’t China prioritise national interest in a climate crisis? If we don’t believe China action/excuses in a pandemic why would we believe China action/excuses on climate change? If we can acknowledge China is trying to exploit the health crisis geo-strategically (i.e. South China Sea military manoeuvres) and geo-economically (belt and road and coercive threats), why will it not exploit climate change in the exact same way?

May 1, 2020

Theodore Dalrymple on the authoritarian innovations we’ve so meekly accepted thanks to the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic

Getting back to “normal” is going to be much more difficult now that the powers-that-be know for certain that we’re all quite comfortable tugging the forelock and bending the knee given the right kind of orders:

Armed Metropolitan Police near Downing Street in London.

Photo by Stanislav Kozlovskiy via Wikimedia Commons.

As for the collective or political lessons of the epidemic, I fear them more than rejoice in them. They seem to me likely to reinforce a tendency to authoritarianism, and to embolden bureaucrats with totalitarian leanings. One of the surprising things (or perhaps I should say the things that surprised me) was how meekly the population accepted regulations so drastic that they might have made Stalin envious, all on the say-so of technocrats whose opinions were not completely unopposed by those of other technocrats. There was, as far as I can tell, no popular demand for the evidence that supposedly justified the severe limitations on freedom that were imposed on the population. I suppose an encouraging interpretation of this readiness of the population to do as it was told is that it demonstrated that, all the froth and foam of opposition to political leaders notwithstanding, fundamentally the authorities were trusted by the population to do the right thing. Much as we lament, therefore, the intellectual and moral level of our political class, there are limits to how much we despise it. In other words, we believe that our institutions still work even when guided or controlled by nullities.

A less optimistic interpretation, as usual, is possible. Our population is now so used to being administered, supposedly for its own good, under a regime of bread and circuses, that it is no longer capable of independent thought or action. We have become what Tocqueville thought the Americans would become under their democratic regime, namely a herd of docile animals. Only at the margins — for example, the drug-dealers of banlieues of Paris — would the refractory actually rebel against the regulations, and that not for intellectual reasons or in the name of freedom, but because they wanted to carry on their business as usual. (I should perhaps mention here that I number myself among the sheep.)

In Britain, at any rate, the epidemic revealed how quickly the police could be transformed from a civilian force that protects the population as it goes about its business into a semi-militarised army of quasi-occupation. This transformation is not entirely new, alas; it has been a long time since the policeman was the decent citizen’s friend. Under various pressures, not the least of them emanating from intellectuals, he has become instead a bullying but ineffectual keeper of discipline, whom only the law-abiding truly fear.

I first sensed this development many years ago this when a traffic policeman asked to see my licence. “Well, Theodore …” he started, calling me by my first name when a few years before he would have called me “Sir.” This change was significant. I had gone from being his superior, as a member of the public in whose name he exercised his authority, to being a kind of minor, whom it was his transcendent right to call to order. He was now the boss, and I was now the underling.

The change in uniform, too, has worked in the same direction. Traditionally, since the time of Sir Robert Peel, the uniform of the British policeman was unthreatening, deliberately so, his authority moral rather than physical. Now, he is festooned with the apparatus of repression, if not of oppression, though in effect he represses very little of what ought to be repressed in case it fights back. The modern police intimidate only those who do not need deterring; those who do need it know that they have nothing much to fear from these whited sepulchres, these empty vessels. Incidentally, the French police have undergone a similar deterioration in appearance: gone is the reassuring képi in favour of the moron’s baseball cap, and some of them now dress in jeans with a black shirt with the word POLICE across its back, which is not difficult to imitate and makes it impossible to know whether a policeman really is a policeman or a lout in disguise.

The Covid-19 epidemic has come as a great boon to the British police. Increasingly criticised for their concentration on pseudo-crimes such as hate speech at the expense of neglecting real crimes such as assault and burglary, to say nothing of organised sexual abuse of young girls by gangs of men of Pakistani origin, they could now bully the population to their heart’s content and imagine that in doing so they were performing a valuable public service, preserving the law and public health at the same time. Thus they transformed their previous moral and physical cowardice into a virtue.

Of course, in bullying the average citizen who was very unlikely to retaliate they took no risks, unlike with genuine wrongdoers and law-breakers, who tend to be dangerous; but the fact remains that most individual policemen joined the force motivated by some kind of idealism, a desire to do society some service, though they soon had these naïve fantasies knocked out of them by the morally corrupt or bankrupt leadership of the hierarchy which owes its ascendency to its willingness to comply with the latest nostrums of political correctness. The faint embers of the policeman’s initial idealism were no doubt rekindled by the opportunity to prevent the spread of the virus, as they supposed that they were doing, but some of them, at least, far exceeded even their flexible and vaguely-defined authority and began to inspect citizens’ shopping bags to determine whether they were hoarding goods that might be in short supply. This was a step too far, and at last there were protests; the police desisted.