Military History Visualized

Published 15 Nov 2016A comprehensive view that compares submarine warfare in the First and Second World Wars. Due to the lack of a submarine warfare in the Pacific in World War 1, the Pacific isn’t covered at all, but there will be an episode on it in the future.

Military History Visualized provides a series of short narrative and visual presentations like documentaries based on academic literature or sometimes primary sources. Videos are intended as introduction to military history, but also contain a lot of details for history buffs. Since the aim is to keep the episodes short and comprehensive some details are often cut.

» HOW YOU CAN SUPPORT MILITARY HISTORY VISUALIZED «

(A) You can support my channel on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/join/mhv(B) Alternatively, you can also buy “Spoils of War” (merchandise) in my online shop: https://www.redbubble.com/people/mhvi…

» SOURCES & LINKS «

Milner, Marc: “The Atlantic War, 1939-1945”; in: Cambridge History of the Second World War, Volume 1

Blair, Clay: Hitler’s U-Boat War – The Hunters 1939-1942

Owen, David: Anti-Submarine Warfare – An Illustrated History

Germany & The Second World War – Volume VI

Germany & The Second World War – Volume II

Breemer, Jan S.: “Defeating the U-boat. Inventing Antisubmarine Warfare”. Naval War College Newport Papers 36

https://www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/e…Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg – Band VI.

Das Deutsche Reich und der Zweite Weltkrieg – Band II.

Rahn, Werner: “Die Deutsche Seekriegsfürung 1943 bis 1945”; in: Das Deutsche Reich & der Zweite Weltkrieg, Band X/1, S. 3-276

Erster Weltkrieg – Zweiter Weltkrieg: Ein Vergleich.

U-boat losses by cause

https://web.archive.org/web/201006112…Differences German U-Boat Design WW1 vs. WW2

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorian…» CREDITS & SPECIAL THX «

Song: Ethan Meixsell – “Demilitarized Zone”

February 5, 2020

Submarine Warfare WW1 vs WW2 – Differences & Commonalities

November 20, 2019

The Sinking of the Royal Oak

Eoin MacFreeman

Published 19 Sep 2014STV and History channel documentary to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the sinking of HMS Royal Oak at Scapa Flow in Scotland. With harrowing eye witness accounts from survivors. Narrated by oor Alex Norton. We will remember them.

On 14 October 1939, Royal Oak was anchored at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, when she was torpedoed by the German submarine U-47. Of Royal Oak‘s complement of 1,234 men and boys, 833 were killed that night or died later of their wounds. The loss of the old ship – the first of the five Royal Navy battleships and battlecruisers sunk in the Second World War – did little to affect the numerical superiority enjoyed by the British navy and its allies, but the sinking had considerable effect on wartime morale. The raid made an immediate celebrity and war hero out of the U-boat commander, Günther Prien, who became the first German submarine officer to be awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross. Before the sinking of Royal Oak, the Royal Navy had considered the naval base at Scapa Flow impregnable to submarine attack, and U-47‘s raid demonstrated that the German navy was capable of bringing the war to British home waters. The shock resulted in rapid changes to dockland security and the construction of the Churchill Barriers around Scapa Flow.

August 19, 2019

QotD: Hitler’s “wonder weapons”

Historians have generally thought of the Type XXI [submarine] — along with other systems like the Me 262, V-1 and V-2 rockets, and the Tiger tank — as an example of Wunderwaffen, wonder weapons. Since 1945 many have fixated on the revolutionary military technologies that the Third Reich developed in the last two years of the war. The cultural impetus behind the concept, as implicitly or explicitly acknowledged by historians in the uneven and largely enthusiastic literature on the subject, was an irrational faith in technology to prevail in operationally or strategically complex and desperate situations — a conviction amounting to a disease, to which many in the Third Reich were prone in the latter years of the Second World War. To the extent that it shaped decision making, faith in the Wunderwaffen was a special, superficial kind of technological determinism, a confidence in the power of technology to prevail over the country’s strategic, operational, and doctrinal shortcomings. To the extent that leaders, officers, engineers, and scientists after 1943 believed innovation to be the answer to Germany’s strategic dilemmas, they displayed a naive ignorance of how technology interacts with cultural and other factors to influence the course of events. In particular, they reflected a willful ignorance of the extent to which even substantial technological superiority has proved indecisive in human conflict throughout history.

Marcus Jones, “Innovation For Its Own Sake: The Type XXI U-boat”, Naval War College Review, 2014-04.

June 25, 2019

Plan Z, or How Not to Prepare for The Battle of the Atlantic

Historigraph

Published on 24 Jun 2019Join us in #WarThunder for free using this link and get a premium tank or aircraft and three days of premium time as a bonus: https://gjn.link/Historigraph/190624

If you enjoyed this video and want to see more made, consider supporting my efforts on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/historigraph

To chat history, join my discord: https://discord.gg/vAFTK2D

#WarThunder #PlanZ #Historigraph

Sources:

Jonathan Dimbleby, The Battle of the Atlantic

Jak P. Mallmann Showell, German Navy Handbook 1939-45

Empire of the Deep, Ben Wilson

Philips Payson O’Brien, How the War was Won

Corelli Barnett, Engage the Enemy More Closely

The Encyclopedia of Sea Warfare

Music:

Crypto, Incompetech https://incompetech.comStormfront, Incompetech https://incompetech.com

April 21, 2019

Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, part 13

Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-5-edited/1453).

This will be the last installment I’ll be re-posting here, as discussion with Alex after I obtained a copy of Marc Milner’s North Atlantic Run made it clear that the bulk of the writing up until this point had actually been copied directly from Milner’s book and only lightly paraphrased and re-ordered by Alex. I’ve gone back over the earlier posts and, to the best of my ability, marked all the direct quotes and provided acknowledgements appropriately.

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos are in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 1 — Canada’s navy before WW2

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

Part 3 — The professionals and the amateurs

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Part 6 — New ships, new challenges

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Part 9 — Early-to-mid 1941, The Rocky Isle in the Ocean

Part 10 — The Newfoundland Escort Force and the Canadian corvettes

Part 11 — “Chummy” Prentice and the NEF

Part 12 — Staff needed, training needed, and Commodore Murray’s thankless tasks

Part 13 — Convoy operations, the Americans, and 1941 Drags On

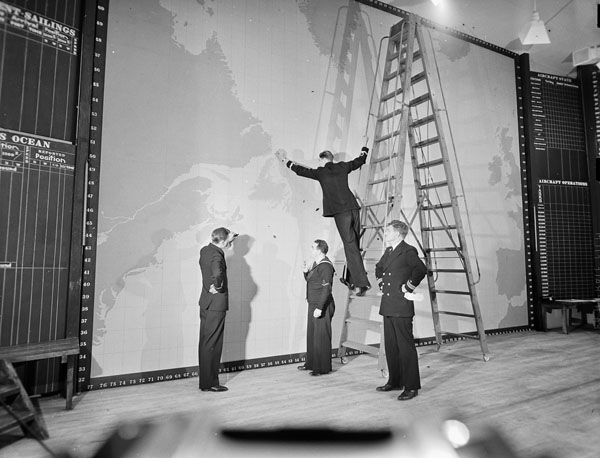

Marc Milner discusses convoy organization in North Atlantic Run:

The organization and sailing of convoys was co-ordinated by the Admiralty’s world-wide intelligence network, of which Ottawa was the North American centre. The assembling of shipping in convoy ports was the responsibility of local NCS staffs working in conjunction with the regional intelligence centre, through which all communication with other regional centres passed. The actual organization of the convoys, issuing code books, charts, special publications, arrangement of pre-sailing conferences, passing out sailing orders, and so forth, was all the work of the NCS.

[Editor’s Note: The command structure for typical Atlantic convoys is discussed in Arnold Hague’s excellent reference work The Allied Convoy System 1939-1945: Its organization, defence and operation:

In typical British fashion, control of the convoy was twofold. Direct control of the convoy rested with the Convoy Commodore, its protection with the Senior Officer of the Escort (referred to in the RN as SOE). As the escort commander was inevitably junior to the Commodore, it was laid down that the Commodore had no right of intervention with the escort, and that the SOE could, if he became aware of circumstances requiring it, give a mandatory instruction to the Commodore. A good deal of tolerance and understanding between the two officers was therefore essential. In fact, friction was minimal, co-operation normally of a high order and the whole system remarkably effective, with the Commodore dealing solely with the merchant ships of the convoy. The SOE intervened (or detailed another escort) at the specific request of the Commodore to provide any assistance required in controlling the convoy.

The divided command system should be seen in the context of the experience of the two commanders. The Commodores, all elderly men, had practical, personal, experience of the problems of coal fired ships from their younger days. As almost all had started their Commodore’s service in the first months of the war they had considerable personal experience of the problems of the Masters whom they led. The escort commanders, much younger officers, lacked that personal knowledge, and the opportunity to obtain it. The system worked in practice, with only rare cases of a personality clash between Commodore and SOE or Commodore and ships’ Masters. In such instances, the Admiralty could exercise its prerogative of dispensing with a Commodore’s services, or appointing him elsewhere. In the only case known to the writer, the offending Commodore, described as “an intolerant personality who greatly upset the Masters of ships in the convoy,” was appointed elsewhere after a short interval. He served the next five years in a single, vital appointment with distinction and great efficiency and, as the Commodore commanding the working-up base at Tobermory in Western Scotland, he was responsible for the training of all newly built or re-commissioned British escort vessels during 1940-45. Indeed not a few RCN and Allied escorts also passed through his hands. He contributed to a very large extent indeed to the efficiency of such escorts and his name became wiedly known and one to respect and admire. His name? Vice-Admiral Sir Gilbert O. Stephenson, also known as the “Terror of Tobermory”.

[…]

Convoy Commodores were drawn from a list of volunteers to serve either with Ocean or Coastal convoys. For the former, the choice was made from retired Flag Officers and Captains of the Royal Navy who were appointed as Commmodores 2nd Class in the Royal Naval Reserve for the period of their duty. … Almost every Commodore was aged over sixty when the commenced his appointment, some older, and their retired ranks varied from Admiral to Lieutenant-Commander. … Commodores for the North Atlantic routes were drawn from a pool of less than 200 who served almost exclusively in that ocean. … Russian convoys drew their Commodores from the North Atlantic pool. Convoy systems organized by the Royal Australian and Royal Canadian Navies, principally coastal, were provided with Commodores appointed by those Services.

All Commodores had the right to request reversion to non-active service at any time, while the Admiralty retained the right (and occasionally exercised it) to retire a Commodore from service.

Commodores were assisted in their duties by a Vice-Commodore and, on occasions, by one or more Rear-Commodores. A Vice-Commodore could be either a Commodore RNR from the pool serving as an assistant or the Commodore of another convoy that had joined at sea. … In all other instances the Vice- and Rear-Commodores were Masters of ships in the appropriate convoy. Their duty was to assist the Commodore and to assume his duties should he be lost during the convoy.

Commodores were accompanied by a staff: a Yeoman of Signals (a Petty Officer of the Communications Branch), three Convoy Signalmen and usually a Telegraphist. They carried considerable responsibility and were, without exception, highly efficient visual signallers. It was also usual to provide the Vice-Commodore with two Convoy Signalmen to assist him in his duties.

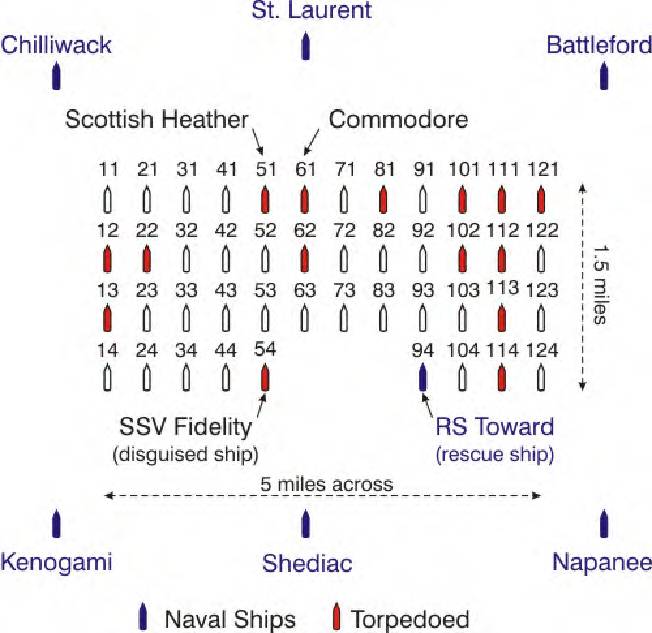

In large trans-Atlantic convoys the commodore sailed front and centre, usually in a large ship which was well appointed for visual and wireless communications with the rest of the convoy and equipped for direct wireless communication with shore authorities. The commodore was also the crucial link between the convoy and its escort. Although the escort commander was ultimately responsible for the safe and timely arrival of the convoy, in practice he and the commodore worked as a team. The vice- and rear-commodores, where needed, were stationed in stern positions on the outer columns of the convoy. Each had his own small staff, largely signallers. Interestingly, the majority of convoy signallers in the North Atlantic by 1941 were RCN.

Marc Milner outlines convoy routing in North Atlantic Run:

Once the convoy cleared the outer defences of the harbour, it became the responsibility of the escort forces. Its routing, however, was laid down prior to sailing by the RN’s Trade Division (shared with the USN after the American entry into the war), which prescribed a series of points of longitude and latitude through which the convoy was to pass. Minor tactical deviations within a narrow band along the convoy’s main line of advance were permitted the SOE, but major alterations of course remained the prerogative of shore authorities. The ideal routing, one towards wich the Allies moved much more slowly than they would have liked, was one simple “tramline” along the most direct course between North America and Britain — the great circle route. For a number of reasons tramlines were not feasible until 1943. For the greater portion of the period covered by this study the object of routing remained simple avoidance of the enemy, within the limits of air and sea escorts.

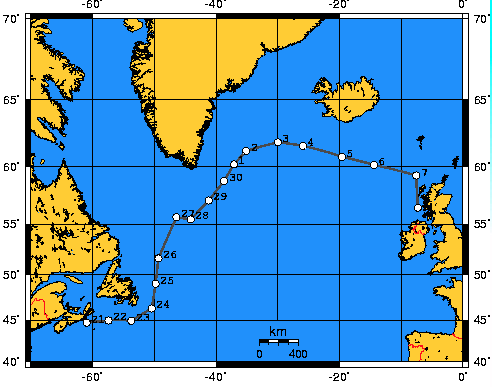

Convoy chart for convoy HX-134, departed on 20 June, 1941, arrived in Liverpool 9 July, 1941.

Image from the Convoy Web Convoy Charts page – http://www.convoyweb.org.uk/extras/index.html

The fast and slow convoy system had undergone some changes by mid-1941. Fast convoys from Halifax were still faster than 9 knots, but ships capable of moving faster than 14.8 knots were routed independently now. Slow convoys from Sydney, Cape Breton were ships capable of speeds between 7.5 and 8.9 knots. Their slow speed drew together a decrepit class of aged tramps, and there was initially no plan to convoy them through the winter. It soon became clear to the staff that all merchant shipping below a certain speed needed to be convoyed, otherwise the loss rate was far too high. For the ships and crews of the escort groups it was a thankless task: slow convoys were notorious for ill-discipline and inattention to signals. The older, slower ships were prone to excessive smoke (endangering the whole convoy by making easier to detect at a distance), breaking down, straggling (falling behind the convoy, beyond the protective screen of escorts sometimes to the point of losing contact with the convoy altogether), or even sailing ahead of the convoy “if stokers happened upon a better-than-average bunker of coal”. Slow convoys were said to more often resemble a mob than an orderly assemblage of ships, and their slow speed made evasive action difficult, if not impossible.

Unidentified signals personnel at the flag locker of the armed merchant cruiser HMCS Prince David in Halifax, Nova Scotia, January 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-104500

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

By the time [Commodore] Murray arrived to take command of NEF it had grown to seven RN and six RCN destroyers, four RN sloops, and twenty-one corvettes, all but four of them RCN. The Admiralty would have liked even more committed to NEF. Indeed, in early July the Admiralty proposed to NSHQ that Halifax be virtually abandoned as an operational base and that the RCN’s main effort be concentrated at St John’s. Naval Service HQ might have expected grander British plans for St John’s when the Admiralty recommended that Commodore Murray command NEF instead of the RCN’s initial choice, Commander Mainguy. For practical reasons, however, concentrating the entire fleet at St John’s was impossible. In the summer of 1941 there were not enough facilities to support NEF, let alone the RCN’s whole expansion program, and it would be a long time before this situation was reversed. The Naval Council did not debate long before the idea was dismissed as impractical. None the less, subtle British pressure to increase the RCN’s commitment to St John’s was continued, in large part because the RN wanted to eliminate its involvement in escort operations in the Western Atlantic. In August, for example, the Admiralty advised the RCN that it preferred to deal with only one operational authority in the Western Atlantic, CCNF. The pressure, in combination with a serious German assault on convoys in NEF’s area by the late summer, proved successful. Despite growing USN involvement in convoy operations in the Western Atlantic, fully three-quarters of the RCN’s disposable strength was assigned to NEF by the end of the year. In spring of 1941, however, the RCN was unprepared to make such large-scale commitments.

One week after Murray assumed his post as CCNF, NEF fought its first convoy battle. Ironically, the confrontation was brought about by the increasing effectiveness of Allied convoy routing as a result of the penetration of the U-boat ciphers in May. Excellent evasive routing so reduced the incidence of interception that the U-boat command, out of frustration, broke up its patrol lines and scattered U-boats in loose formation. This made accurate plotting by Allied intelligence much more difficult and consequently made evasive routing less precise.

The first action against enemy submarines for the NEF occurred on the 23rd of June, 1941. Convoy HX-133 comprised fifty-eight ships eastbound from Halifax escorted by the destroyer HMCS Ottawa (SOE, Captain E.R. Mainguy) and the corvettes, HMCS Chambly, Collingwood, and Orillia. At some point during the day, the convoy was sighted by U-203, which communicated the convoy position to U-boat command and continued to shadow from a distance. U-203 attacked on the night of 23-24 June, easily penetrating the thin screen of escorts to sink a merchant ship. The SOE found it impossible to co-ordinate the escorts’ defence or to direct any search for the submarine because the corvettes were not fitted with radio telephones and their wireless sets were unable to reliably stay in communication with the SOE. Only Chambly logged receiving signals from Ottawa, but only half of them. On the 26th, Ottawa established an ASDIC contact and attacked and two of the corvettes came to assist, Commander Mainguy instructed the corvettes to stay and keep the U-boat submerged while the destroyer re-joined the convoy. The message, sent by message light, was only partially received, and the corvettes could not get the message repeated. Unable to determine what the order was, both ships broke off the action and returned to the convoy in turn. The escort group was eventually reinforced by RN ships, and although HX-133 lost six merchantmen, the RN escorts sank two of the attacking U-boats. These Canadian problems were lamentable, but hardly unexpected. As Joseph Schull, the RCN’s official historian, concluded, “no one could have expected it to be otherwise”.

Marc Milner picks up the story in North Atlantic Run:

In the meantime, Captain (D), Greenock’s stern criticism of the Canadian corvettes found its way to NSHQ, accompanied by a covering letter from Captain C.R.H. Taylor, RCN, who had succeeded Murray in London as CCCS. Taylor noted that the poor state of readiness of the corvettes stemmed from the fact that they were manned and stored for passage only. Deficiencies could not be made up from the RCN’s UK manning pool since most of the men who were committed to it were in fact still aboard the ships. Taylor also noted that the poor quality of officers, especially COs, had been pointed out in April and that they would never have been assigned if the ships had commissioned permanently. It was heartening to note, however, that Hepatica, Trillium, and Windflower, through remedial work and extra effort, were worked up “to a state of efficiency which the Commodore Western Isles reported as surpassing many RN corvettes”.

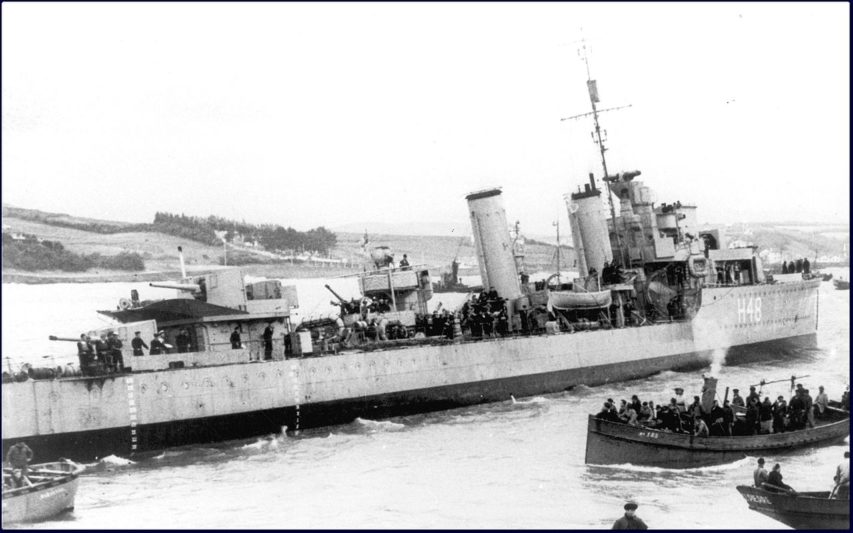

View of HMCS Annapolis from HMCS Hamilton, 30 August, 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence/Library and Archives Canada/PA-104149Naval Service HQ was therefore well braced when a follow-up letter from the Admiralty arrived several days later. The letter took a conciliatory view of Canadian difficulties, noting that these seemed to be “essentially similar to those occasionally experienced with the RN corvettes and trawlers”. To overcome these the Admiralty advised of three means employed by the RN. If the officers and men were competent and responsive, simply prolonging the length of work-up usually sufficed. If the officers were incompetent or otherwise unsatisfactory, they could be replaced by new ones drawn from a manning pool. Similarly, inefficient or unsuitable key ratings could be replaced by men drawn from a pool maintained for this purpose. In its concluding remarks the letter cautioned that corvettes commissioning and working up in Canada were likely to display a wide variation in efficiency, and warned that at this point, with ships stretched to provide continuous A/S escort in the North Atlantic, “no reduction in individual efficiency can be safely accepted”. This was true enough, but it contradicted what the Admiralty had said to the RCN in April, when the issue of manning the ten “British” corvettes had been resolved.

While the Admiralty clearly felt that it was offering the RCN a workable set of solutions, the suggestions contained few alternatives for the Canadians. In sum, the RCN was hard pressed just to find men with enough basic training in order to get the corvettes to sea. Producing a surplus of specialists — of any kind — was out of the question. Nelles, in his draft reply to the Admiralty, pointed out that all experienced officers and men were already committed either to new ships or to the new RCN work-up establishment, HMCS Sambro, at Halifax. Future prospects looked equally grim. Spare HSD ratings (the highest level of ASDIC operator, of which there was to be one per corvette) would not be available until the spring of 1942, a prognosis even Nelles considered optimistic. And no trained RCN commanding officers or first lieutenants could be spared for some time to come. In short, a pool of qualified and disposable personnel was out of the question. If the RN wanted to loan experienced personnel until they could be replaced by the RCN, such help would be “greatly appreciated”. The only other options were prolonged work-ups or some form of ongoing training. Aside from that, Canadian escorts had to make do. RCN escorts sent to work up at Tobermory through 1941 continued to arrive in an unready state, though here is no indication that these were any worse off than corvettes retained for work-up in Canada. The state of ships arriving in Tobermory not only resulted in “much excellent training [being] lost”; it did little to enhance the RCN’s already tattered image within the parent service.

[Editor’s Note: The training at Tobermory really was both intense and nerve-wracking for RN and RCN crews alike, as James Lamb recounts in The Corvette Navy:]

… the really soul-testing experience, the one that every old corvette type still recalls today with a shudder, came with the two-week work-ups for newly commissioned ships, designed to make a collection of odds and sods into an efficient ship’s company. There were such bases at Bermuda, St. Margaret’s Bay, and Pictou on the Canadian side, but the one that really left a lot of scar tissue was the old original, the Dante’s Inferno operated at Tobermory on the northwest coast of Scotland by the redoubtable Vice-Admiral Gilbert Stephenson, Royal Navy. This legendary character, variously known as “Puggy”, “The Lord of the Isles”, or more commonly “The Old Bastard”, inhabited a former passenger steamer, The Western Isles, which lay at anchor in the quiet, picturesque harbour, surrounded by a handful of newly commissioned corvettes, like a spider surrounded by the empty husks of its victims. He was a daunting sight, smothered in gold lace and brass buttons, with a piercing blue eye that could open an oyster at thirty paces, and tufts of grey hair sprouting from craggy cheeks, and he preyed like some ravening dragon upon the callow crews and shaky officers served up to him at fortnightly intervals.

At the end of each day, an exhausted crew would tumble into their hammocks, but there was no assurance of uninterrupted slumber. On the contrary; the monster stalked its unwary prety by dark as well as by light, and seldom a night passed without an alarm of some sort. For the Admiral delighted in midnight forays; more than one commanding officer was shaken awake to find himslef staring into the piercing eyes of a malevolent Admiral and learn that his gangway had been left unportected, that his ship had been taken, and that his kingdom had been given over to the Medes and the Persians.

But occasionally — just occasionally — the ships got a little of their own back. There was the occasion when the Admiral in his barge, lurking soundlessly under the fo’c’sle of what he hoped to be an unsuspecting frigate, waiting for the sailor whom he could hear humming to himself on the deck above to move on, suddenly found himself being urinated on, “from a great height”, as gleeful narrators related the story in a hundred rapturous wardrooms. There was the other frigate he boarded one dark night only to be set upon by a ferocious Alsatian dog and fored to leap back into his boat, leaving, in the best comic-strip tradition, a portion of his trouser-seat aboard the ship, which ever after displayed the tattered remains as a proud trophy, suitably mounted and inscribed.

And there was the Canadian corvette sailor who worsted the fiery Admiral in a hand-to-hand duel. Coming aboard this ship, the Admiral suddenly removed this cap and flung it on the deck, shouting to the astounded quartermaster: “That’s an unexploded bomb; take action, quickly now!”

With surprising sang-froid, the youngster kicked the cap over the side. “Quick thinking!” commended the Admiral. Then, pointing to the slowly sinking cap, heavy with gold lace, the Admiral continued: “That’s a man overboard; jump to it and save him!”

The ashen-faced matelot took one look at the icy November sea, then turned and shouted: “Man overboard! Away lifeboat’s crew!”

The look on the Admiral’s face, as he watched his expensive Gieves cap slowly disappear into the depths while a cursing, fumbling crew attempted to get a boat ready for lowering, was balm to the souls of all who saw it.

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

Although reports from both sides of the Atlantic indicated that the expansion fleet was badly in need of training and direction, its future looked bright in the summer of 1941. Corvettes operating from Sydney and Halifax as part of the Canadian local escort held up remarkably well to operations in the calmer months. A sampling of escorts based at Sydney in the months of August and September reveals startling statistics on the small amount of sea and out-of-service time logged by the new ships. Considerably less than half of their days were spent at sea, and this represented only about 56 percent of their seaworthy time. With so much time alongside, ships’ companies were able to keep up with teething problems. In the ships in question all time out of service was devoted to boiler cleaning. … Later, as operations crowded available time and spare hands crowded the mess decks to provide extra watches for longer voyages, the shorter period became routine. But it is significant that until the fall of 1941 the corvette fleet enjoyed considerable slack, in which it could make good its defects.

The easy routine extended to NEF as well and offered an opportunity to improve on the operational efficiency of escorts already committed to convoy duties. “As the force is now organized,” Captain E.B.K. Stevens, RN, Captain (D), Newfoundland, wrote in early September, “there is ample time for training ships, having due regard for necessary rest periods between convoy cycles.” It would be a year and a half, or more, before the same could be said again. Moreover, when the Canadian escorts did have slack time, the dearth of training equipment at St John’s was, as Stevens reported, “a beggar’s portion”; one wholly inadequate target borrowed from the United States Army and one MTU (mobile A/S training unit) bus suitable for training destroyers (although corvette crews could be and were trained on it).

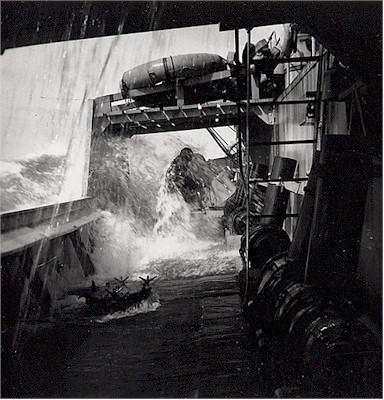

Personnel preparing to fire depth charges as the destroyer HMCS Saguenay attacks a submarine contact at sea, 30 October 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-204329Captain (D)’s concern for the languishing advance to full efficiency arose from recent gunnery exercises off St John’s. “It is noticeable,” NEF’s gunnery officer reported, “that everyone from the First Lt., who is Gunnery Control Officer, downwards put their fingers to their ears each time the gun fired.” Not surprisingly, this prevented the ship’s gunnery officer from observing the fall of the shot, since he could not possibly use his glasses with his hands thus employed. In addition, some of the guns crews were startled by the firing, and all of this contributed to a deplorable rate of three rounds per minute. Captain (D) drily concluded that “At present most escorts are equipped with one weapon of approximate precision, the ram.” And so it remained for quite some time.

What NEF really needed, of course, was a proper training staff, hard and fast minimum standards for efficiency, the will to adhere to them, and improved training equipment. A tame submarine would have been a distinct advantage, but by the time L27, the submarine assigned to NEF by Western Approaches Command, arrived from Britain later in the fall, there was no time set aside for training. Throughout 1941 only hesitant and largely unsuccessful attempts were made to rectify this situation. In August, Prentice obtained permission from Murray to establish a training group for newly commissioned ships arriving from Halifax. The crews of these were found to be totally “inexperienced and almost completely untrained”. Unfortunately, as with other such attempts, Prentice’s first training group was stillborn because of increased operational demands at the end of the summer. So long as the training establishment at Halifax produced warships of such questionable quality, operations in the mid-ocean suffered, and it would be some time before the home establishments switched their emphasis from quantity to quality.

Relief for the struggling escorts of NEF was in the offing from two directions as summer gave way to autumn. By the end of August 1941 nearly fifty new corvettes were in commission, including those taken over from the RN. More were ready, at the rate of five to six per month, before the end of the year. With the men, the ships, and a little time and experience, the nightmare of jamming two years of expansion into one would be ended. This optimistic view was enhanced by the increased involvement of the USN in NEF’s theatre of operations and by the prospect that many of its responsibilities would be passed to the Americans.

The Americans had hardly been passive bystanders in the unfolding battle for the North Atlantic communications. The westward expansion of the war threatened to bring an essentially European conflict to the Western Hemisphere. Certainly, it disrupted normal trade patterns. With the establishment of American bases in Newfoundland in late 1940 that island became for the US what it was already for Canada — the first bastion of North American defence. But neither the US president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, nor American service chiefs were content to rest on the Monroe Doctrine. Moreover, aside from the purely defensive character of US involvement in Newfoundland, the Americans made an enormous moral, financial, and industrial commitment to the free movement of trade to Britain with the announcement of Lend-Lease in March 1941. A natural corollary to lend-lease was what Churchill called “constructive non-belligerency”, the American protection of US trade with Britain. While Britain would clearly have liked a more rapid involvement of the US in the Atlantic battle, American public opinion would only stand so much manipulation. Therefore, it was not until August that Roosevelt felt confident enough to meet Churchill and work out the details of American participation in the defence of shipping.

Conference leaders during Church services on the after deck of HMS Prince of Wales, in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, during the Atlantic Charter Conference. President Franklin D. Roosevelt (left) and Prime Minister Winston Churchill are seated in the foreground. Standing directly behind them are Admiral Ernest J. King, USN; General George C. Marshall, U.S. Army; General Sir John Dill, British Army; Admiral Harold R. Stark, USN; and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, RN. At far left is Harry Hopkins, talking with W. Averell Harriman.

US Naval Historical Center Photograph #: NH 67209 via Wikimedia Commons.A great deal has been written about Roosevelt’s and Churchill’s historic meeting at Argentia, Newfoundland, in August 1941. Here it is only important to note how the agreements directly affected the conduct and planning of RCN operations in the North Atlantic. The British and Americans decided, without consultation with Canada, that strategic direction and control of the Western Atlantic would pass to the US as per ABC 1. Convoy-escort operations west of MOMP became the responsibility of the USN’s Support Force (soon redesignated Task Force Four), with its advanced base at Argentia, Newfoundland.

April 12, 2019

Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, part 10 by Alex Funk

Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-4/1447/3).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 1 — Canada’s navy before WW2

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

Part 3 — The professionals and the amateurs

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Part 6 — New ships, new challenges

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Part 9 — Early-to-mid 1941, The Rocky Isle in the Ocean

Part 10 — The Newfoundland Escort Force and the Canadian corvettes

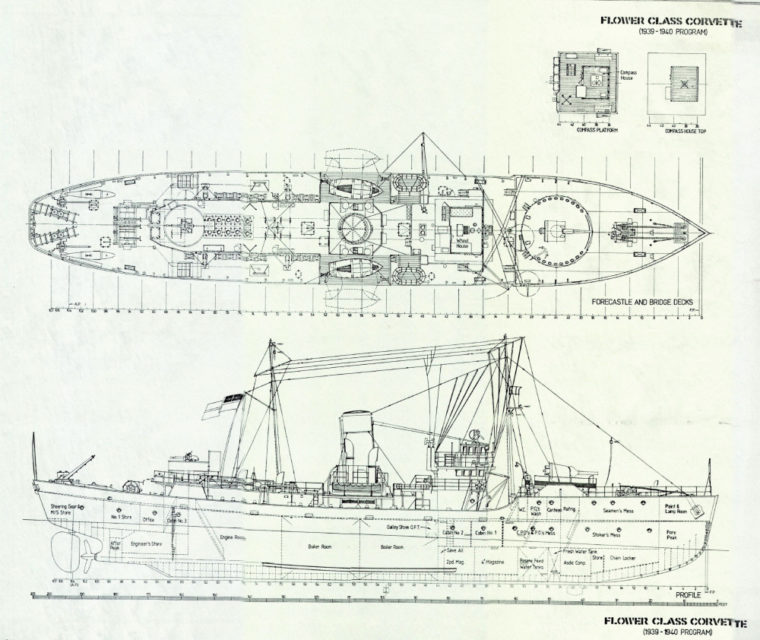

Returning to the corvettes themselves for a moment, while I have already spoken of the diversity of the modifications that they would receive [in Part 7], it is important to discuss the modifications that Canadians gave to their own corvettes in comparison to those made to Royal Navy ships. The RN used its corvettes for ocean escort and had begun to implement some of the modification to individual ships of the class to make the vessels more suitable for work on the open sea. The lengthened forecastle increased available crew space (required as ships’ crews were augmented with extra ratings for the newer equipment being fitted) and helped to make the ships’ interior spaces significantly drier. The bows were also strengthened to take the pounding of the heavy seas typically encountered in the North Atlantic. The first Canadian-built corvettes could have been delayed in order to incorporate these changes while still in the builders’ hands, but the shortage of ships meant that they went ahead largely as originally planned. The major Canadian alteration of the original design reflected the corvettes’ intended coastal operational role: minesweeping gear. The alterations to the original design, involving modification of the quarter-deck, cutting back the engine-room casing to accommodate a steam winch, broadening the stern to fit both the minesweeping wires and the depth charge rails, and the extra storage for the minesweeping gear when not in use, had already delayed the delivery of the ships to the navy.

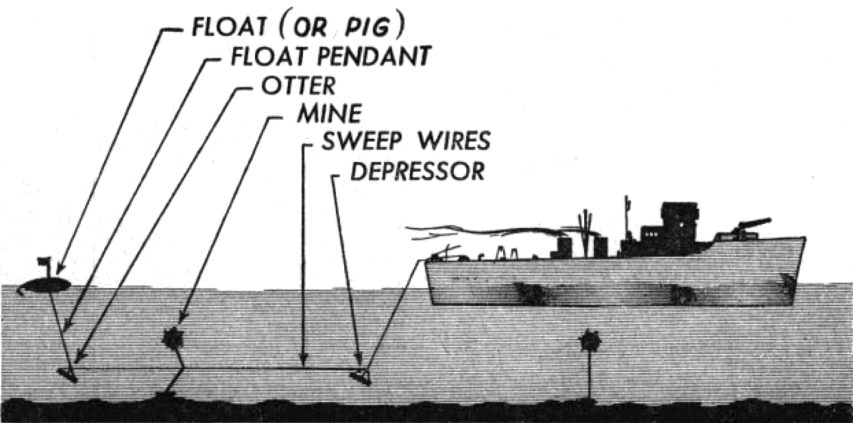

[Editor’s Note: Minesweeping, while not the primary intended role for the Flower-class corvettes (especially without gyrocompasses!), was a viable alternate task. Here’s a post-war diagram of how WW2 minesweeping was done (from History on the Net‘s Minesweepers of WW2 page)]:

[Minesweeper-equipped ships would] “sweep” anchored mines by cutting their mooring ropes or chains, permitting the mines to float to the surface where they could be destroyed by gunfire.

Magnetically activated “influence” mines were defeated with a strong electrical current passed through a loop of cable, neutralizing the detonator. Acoustic mines, which responded to the noise of a ship’s engines and propellers, were prematurely detonated by underwater noisemakers operating on suitable harmonic frequencies.

RCN personnel preparing to launch a minesweeping float from HMCS Alberni off the coast of British Columbia, March 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-179942

Marc Milner, North Atlantic Run:

All of this delayed completion and may have hardened the Staff to any further delays occasioned by major alterations. Moreover, that the Naval Staff was not unduly concerned about the A/S performance of the corvettes is evidenced by the fact that the addition of a full minesweeping kit “had an adverse effect on the operations of the A/S gear”. The latter, as the Staff went on to observe, was carried forward and was affected by the corvette’s tendency to trim by the stern when fitted for minesweeping. In practice, however, the original corvette design, when fully stored and armed, tended to trim by the bows, which also affected A/S efficiency. The addition of extra weight in the stern may unwittingly have compensated for the design fault.

More important in terms of sea-keeping and habitability in deep-sea operations was the extension of the foc’sle. News of this major alteration reached NSHQ while most of the vessels of the first program were still in the builders’ hands. Although the RCN would make allowances for more crewmen, better refrigeration, a more powerful wireless set, and more depth charges — all indications that corvettes were expected to go farther afield and stay longer — the navy did not act on this fundamental alteration in basic structure of its first sixty corvettes. However, the Staff did recognize the value of the design improvements. … In the meantime, the RCN plodded along with escorts which, as late as the end of 1940, the navy still considered inshore auxiliaries. In any event, corvettes were still tied closely to the defended-port system under the terms of Plan Black. It is also arguable that the Staff’s failure to extend the foc’sles of corvettes when it had the chance stemmed from the navy’s need of ships to permit expansion really to begin, or from the increasing gravity of the war at sea. Whatever the case, it was a lost opportunity that would come to haunt the navy.

The forecastle extension (or lack thereof) would come to be the norm for the RCN and NSHQ: certain trivial modifications seemingly at random, major ones delayed exponentially. The after gun platform (for the Pom-Pom) was moved further to the rear of the ship so that it was not in danger of blowing away the mainmast, and would remain further to the rear long after the secondary mast was discarded. Shortage of primary AA armament saw a number of .5-inch Colt and Browning machine guns acquired from the U.S. and fitted in twin mounts (two in the aft gun position and one twin-mount on either side of the bridge). Inability to acquire sufficient Colt or Browning machine guns meant the return of the Lewis guns.

Other differences between RN and RCN corvettes were much less noticeable, but had a more important effect on the performance of the ships as deep-sea escorts. There was, for example, no provision in Canadian plans for a breakwater on the foc’sle of original corvettes. Without it, water shipped forward was able to run aft and pour into the open welldeck — the crew’s main thoroughfare. The British soon corrected this, but the RCN moved with incredible slowness on this simple matter, and as a result Canadian corvettes were unnecessarily wet. Canadian corvettes were also completed without wooden planking or some form of synthetic deck covering to prevent slipping in the waist of the ship, where the depth-charge throwers were fitted. Since this area was also constantly wet, the difficulties of loading charges can be imagined.

The most telling shortcoming of Canadian corvettes, and the one that was to cause the most difficulty in the struggle for efficiency, was the lack of gyro-compasses. The latter were at a premium in Canada, so the Naval Staff decided to fit them to the Bangor minesweepers, whose need for accurate navigation was paramount. The first Canadian-built corvettes (including those built to Admiralty accounts) were equipped with a single magnetic compass and the most basic of ASDIC, the type 123A. Even by 1939 standards the 123A was obsolete and in the RN was considered only suited to trawlers and lesser vessels. The 123A’s standard compass, graduated in “points” and not in degrees, made it equally hard for captains to co-ordinate operations between two ships or to undertake accurate submarine hunts and depth-charge attacks. The single binnacle and its attendant trace recorder were mounted in a small hut, above the wheelhouse. During an action it was impossible for a captain to be both in the ASDIC hut and outside on the bridge wings, the only place from which he could obtain an overall perspective on the situation. Nor was the needle of the standard compass properly stabilized, a deficiency particularly noteworthy in such lively ships as corvettes. … As a final point, it should be noted that compasses were also susceptible to malfunction from the shock of firing the main armament, exploding depth charges, or simply from the pounding of the ship at sea. The tendency of Canadians to launch inaccurate depth charge attacks proved a source of continuous criticism from British officers.

Officers on the bridge of Canadian Flower class corvette HMCS Trillium, circa 1940-42.

Image from the Canadian Navy Heritage website, Image Negative Number JT-159, via Wikimedia Commons.

Partly because of a disparity of resources, partly because there was still a lot of ambiguity concerning the role that the corvettes (and the RCN) would play in the war in general, the RN corvettes outclassed RCN corvettes when it came to performance at sea. Misapplication of Staff energies also played a role.

Instead of laying down a basic policy for the engineer-in-chief to follow, the Staff haggled over every conceivable alteration to their corvettes. They insisted, for example, that inclining tests be done before .5-inch machine guns were authorized for the bridge wings, even though they knew full well that this practice had already been adopted for comparable British ships. In the final analysis it would have been much better had the RCN continued its initial practice of calling its own corvettes “Town class”, after its policy of naming them for small Canadian communities. Instead the practice was abandoned in deference to the Admiralty’s choice of “Town class” for the ex-American destroyers, and the RCN applied the British class name of “Flower” to its corvettes. Had the RCN stuck to its distinctive class name, the tremendous differences which were to prove so very important by 1942-43, might have been as apparent as they were real.

Deck awash on HMCS Trillium, circa 1943

National Archives of Canada PA-037474, via HMCS Trillium page of the For Posterity’s Sake website – http://www.forposterityssake.ca/Navy/HMCS_TRILLIUM_K172.htmNSHQ’s notion that the RCN was to provide convoy escorts for the Newfoundland focal area suggests that the Naval Staff had not made the mental leap from the concept of locally based “strike forces” to the idea of a regional escort force. In this they were not alone. The distinction between two types of operation — one searching for submarines where shipping was plentiful, the other actually protecting the ships towards wich the submarines were drawn — was never very clear in the early days. NEF was, none the less, admirably suited to RCN capabilities. It also met two other vitally important criteria: it supported the government’s geopolitical aspirations and was at the same time fundamental to the war effort.

The war was entering what Churchill called “one of the great climacterics”. On June 22nd, Hitler would invade Russia and soon had her reeling. A Soviet collapse would give Hitler access to enormous resources. Even if Russia could fight them to a stalemate, there could be no Allied victory without an attack supplied by sea and mounted from the British Isles. Whether for the ultimate defence against a stronger Germany or for our own seaborne assault, Allied resources had to be turned into munitions of war and stockpiled in the UK. The resources were more than sufficient, but between the promise of the future and the need of the present lay a perilous gap of space and time that could only be bridged by ships, all the ships now available and hundreds more. Many convoys arrived at British ports each week and the tonnage unloaded was enormous. Yet a great percentage of it was what the island required simply to exist. Only the margin above that daily necessity represented the power to wage war. Munitions, aircraft, guns, tanks, and above all, aviation gasoline and fuel oil. If oil stocks fell below the point of safety, the operation of ships and planes would have to be curtailed. If U-boat attacks could not be met effectively, more ships would be lost, creating further shortages which would again reduce operations. The increasing demands of the war had to be met by a corresponding increase in the flow of cargo.

The U-boats imposed a steady drain: three merchant ships were going down for every one replaced. Eight submarines were coming into operation for every one sunk. U-boats swarmed in the Mediterranean. They were off Gibraltar, off the Cape Verde Islands at the bulge of Africa, off Cape Town far to the south. By the virtue of St John’s position alone, it bridged nearly a quarter of the gap between the Canadian seaboard and Iceland. June 1941 would also see Canada’s Commodore Murray return from Britain to become Commodore Commanding Newfoundland Escort Force. From Liverpool, the RN’s Commander-in-Chief Western Approaches, Admiral Sir Percy Noble, directed the whole Atlantic battle, but Commodore Murray exercised autonomy within his own war zone. The Newfoundland Escort Force was made up of six Canadian destroyers and seventeen corvettes, plus seven destroyers, three sloops and five corvettes of the RN. Soon more ships, French, Norwegian, Polish, Belgian and Dutch, were allotted to Commodore Murray. His authority extended to all local escorts operating from St. John’s and to convoys and their escorts while in Newfoundland waters.

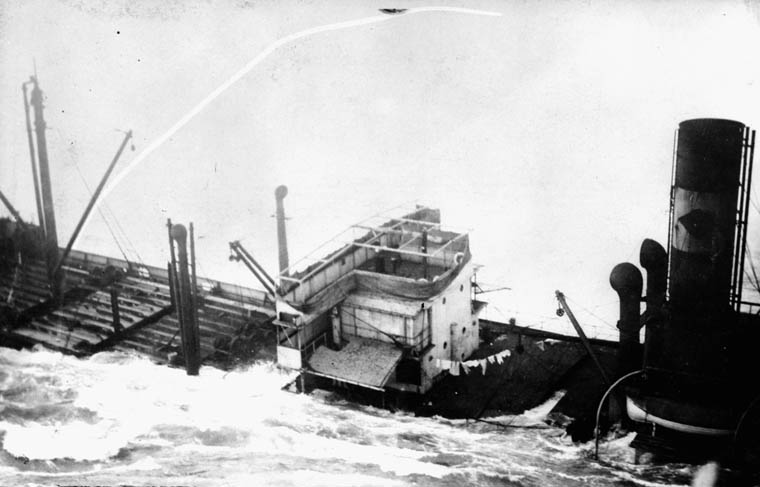

SS Rose Castle sinking and decks awash, 2 November, 1942. The original description for this item gives the date October 1942 as the date of the sinking, but according to eyewitness and survivor Gordon Hardy, the Rose Castle sank at 3:30 AM, November 2, 1942. On Oct 20, 1942, the Rose Castle was hit by a dud torpedo but was not damaged.

Library and Archives Canada/PA-192788

April 10, 2019

Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, part 9 by Alex Funk

Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-4/1447/3).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 1 — Canada’s navy before WW2

Part 2 — The Admiralty takes control

Part 3 — The professionals and the amateurs

Part 4 — 1940: The fall of France, the battle begins, and the RCN dreams of expansion

Part 5 — The RCN’s desperate need for warships

Part 6 — New ships, new challenges

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Part 9 — Early-to-mid 1941, the Rocky Isle in the Ocean

Marc Milner continues the story in North Atlantic Run:

The problem of providing end-to-end A/S escort in the North Atlantic was discussed by British and Canadian authorities during the winter. These talks were the first sure indication that RCN corvettes were likely to be used as ocean escorts (what the navy thought corvettes earmarked for the Eastern Atlantic were initially expected to do remains uncertain). In any event, the Anglo-Canadian discussions identified three factors crucial to the establishment of end-to-end A/S escort: the escorts must be available; they must have reached a reasonable state of individual and escort-group training, and the necessary bases must be available. In May 1941 none of these factors obtained in the Western Atlantic. An insufficient number of new corvettes were in commission, and most of these only recently. The development of facilities was now a top priority, but support facilities outside of Halifax were virtually non-existent, and the standard of training was to prove inadequate, to say the least.

The natural place from which to stage escort operations in the Northwest Atlantic was Newfoundland.

To briefly discuss Newfoundland’s role so far, when Canada declared war on September 10th, Newfoundland had already been at war for seven days. As a British dominion [under direct rule from London since 1934] ten years before joining Confederation, the mainland declaration of war received modest space on page four of the St. John’s Evening Telegram. They had participated in the first “hostile” act in North America: a German merchant vessel had been seized and thirty prisoners taken. The local YMCA was converted into a prison. Rationing and dim-outs took effect instantly. Private radio stations were silenced, mail and cables censored, aliens registered and controlled. Insurance premiums on waterfront property had gone up in less than a week from $1.00 to $5.00 for each $1000 of coverage.

View of the entrance to St.John’s harbour and port facilities, Newfoundland, taken from Signal Hill, 1942. A minesweeper is leaving port.

Canada. Department of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / ecopy

Milner continues:

Although not yet part of the Dominion of Canada, the island was integral to Canadian defence, and its protection was assumed, in consultation with the British, as a Dominion responsibility in 1939. By early 1941, however, the Canadian armed forces had made only a modest contribution to Newfoundland’s security, though more was planned under the terms of Plan Black. During 1940 the RCN had surveyed the coast for possible base sites and fleet anchorages and ordered a further ten corvettes for local defence. The navy had also seconded personnel to the Naval Officer in Charge, St John’s, Captain C.M.R. Schwerdt, RN, the only naval establishment on the island. Until the latter was turned over to the RCN in early May 1941, the Canadian navy had no permanent presence in Newfoundland. For a number of reasons, not all of them enemy inspired, this low level of activity was destined to change. The absorption of Schwerdt’s command into the RCN came as part of the integration of Newfoundland into the Canadian east-coast command system, and it mirrored similar army and air force arrangements. But Canada was also engaged in an embryonic war of influence with the U.S. over the old colony. The establishment of American bases on the island, as a result of the destroyers-for-bases deal with the British, was attended by an agreement granting the U.S. rights to defend its new bases by operations in adjacent territory. The agreement was concluded despite strong protests from Canada and in spite of the prior Canadian acceptance of responsibility for Newfoundland’s defence.

The anxiety Canada felt over her position in Newfoundland was exacerbated by joint Anglo-American planning of a combined strategy for the defeat of Germany should the U.S. enter the war. For several weeks in early 1941 senior American and British staffs met in Washington to discuss a co-ordinated Commonwealth and U.S. plan. Neither Canada nor any of the other Dominions was accorded official representation, although British delegates kept their Commonwealth allies informed of proceedings. The result of these meetings was an agreement, American-British Conference 1 (ABC 1), whereby the world was divided into two basic strategic zones. The Americans were to assume responsibility for most of the Pacific and for the Western Atlantic, with the exception of waters and territory assigned to Canada “as may be defined in United States-Canada joint agreements”.

The Canadians were not pleased with their treatment in the Anglo-American discussions, and the Chiefs of Staff feared that ABC 1 was intended to oust them from Newfoundland. The issue was somewhat problematical, since the implementation of ABC 1 was dependent upon U.S. entry into the war. However, the resolution of such issues, which had a direct bearing on Canada’s responsibilities as a sovereign state, did not accord with the national view of Canada as a full and independent partner in the war against Germany. Canada was already attempting to force recognition of that claim, at least with respect to North American defence, by the establishment of a Canadian Staff mission in Washington. While the battle to be heard and recognized went on, Canadian responsibilities under under the terms of ABC 1 were worked out by the Permanent Joint Board on Defence. These agreements, styled Joint Canadian-United States Basic Defense Plan No. 2 (Short Title ABC-22) and appended to ABC 1, acknowledged Canada responsibility for her own coastal waters (within the customary three mile limit) and for the commitment of five destroyers and fifteen corvettes to supplement USN forces in the Western Atlantic. Under the terms of ABC 22 the balance of Canadian naval forces was to be sent overseas.

[Editor’s Note: The actual wording of Annex 1 to ABC 22 isn’t quite as restrictive as far as available naval forces are concerned, and the inventory of USN and RCN forces is interesting in itself:]

ANNEX I-MILITARY FORCES

In view of the uncertainties which exist as to the stability of the strategic situations in various theatres, and as to the date on which the United States may enter the war, the strengths of forces listed below must be regarded as subject to change in the light of the strategic situation which may exist when the plan is placed in effect. The forces now estimated to be initially available for the operations required by this plan as of 15 July, 1941, are:

(A) ATLANTIC Ocean Escorts United States Atlantic Fleet 6 Battleships 5 8" Cruisers 54 Destroyers 4 Mine Sweepers (destroyer type) 54 Patrol Planes North Atlantic Naval Coastal Force (U. S. N.) 5 Eagle Boats 3 Gunboats 4 Patrol Yachts 18 Patrol Planes Page 1591 Newfoundland Force (R. C. N.) (Allocated to operate with Ocean Escorts, U. S. Atlantic Fleet) 5 Destroyers 15 Corvettes Atlantic Coast Command (R. C. N.) 8 Destroyers 28 Corvettes 4 Mine Sweepers 4 Magnetic Mine Sweepers 11 Armed A/S Yachts

[Editor’s Note: I’d never heard of “Eagle Boats” before, so here’s what Wikipedia has to say about them: “The Eagle class patrol craft were a set of steel ships smaller than contemporary destroyers but having a greater operational radius than the wooden-hulled, 110-foot (34 m) submarine chasers developed in 1917. The submarine chasers’ range of about 900 miles (1,400 km) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h) restricted their operations to off-shore anti-submarine work and denied them an open-ocean escort capability; their high consumption of gasoline and limited fuel storage were handicaps the Eagle class sought to remedy. […] The term “Eagle Boat” stemmed from a wartime Washington Post editorial which called for “…an eagle to scour the seas and pounce upon and destroy every German submarine.” However, the Eagle Boats never saw service in World War I. […] A number of the Eagle Boats were transferred to the United States Coast Guard in 1919, and the balance were sold in the 1930s and early 1940s. Eight Eagle boats saw service during World War II. One was stationed in Miami as a training vessel. After the war, seven were decommissioned, while one was sunk by a German submarine.”]

Milner continues:

In the strictest sense, should the U.S. enter the war, Canada had lost the battle for Newfoundland. But though the Canadians had earlier been prepared to place their forces unreservedly under U.S. strategic direction in the worst-case scenario of Plan Black, they considered ABC 1 and ABC 22 offensive plans. The Canadians therefore clung firmly to their right to exercise command and control of Canadian forces in Canada and Newfoundland, even should ABC 1 come into force. Further, actual command of forces, despite a strong American sentiment to the contrary, was to remain with the respective nations. Co-ordination of the military effort in a given area was to be by “mutual co-operation”. Unified command of all forces under a single officer was allowed for upon agreement by the officers in the field or the Chiefs of Staff. The criteria for determining who was to command under such conditions were never clearly defined; however, the Canadians at least considered that the size of national contingent and the rank and seniority of its commanding officer were the governing elements. It was Canadian practice, therefore, throughout the joint American-Canadian occupation of Newfoundland to keep Canadian strength above that committed by the U.S. and to ensure that the senior Canadian present outranked his American counterpart. All of these considerations were foremost in the minds of the Canadian government and Staffs when Canada was asked by the British to base large escort forces at St John’s in the spring of 1941.

Thus, aside from the very real operational importance of the task, it was not surprising that the RCN responded enthusiastically to the Admiralty’s request of 20 May that the navy begin the escort of convoys from a base at St John’s. NSHQ responded by declaring that it was prepared to commit all of its new construction and its destroyer forces as well — virtually the entire navy. “We should be glad,” the Canadian reply read, “to undertake anti-submarine convoy escort in the Newfoundland focal area.” Naturally, command of the forces would rest with an RCN officer, and NSHQ suggested Commander E.R. Mainguy, RCN, an officer with experience in the Western Approaches who would be promoted to Captain for the task. However, the Canadians agreed that the Admiralty, through the Commander-in-Chief, Western Approaches (C-in-C, WA), would assume “direction of this force when necessary to coordinate its cooperation with those of the Iceland force.”

Commander E.R. Mainguy, Commanding Officer, HMCS Ottawa, off Botwood, Newfoundland in June, 1940. Botwood was being scouted as a potential seaplane base at the time, and would eventually become home to two RCAF Canso squadrons and a full Canadian Army detachment.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-104029Whether Canadian enthusiasm for the Newfoundland Escort Force (NEF) stemmed from a belief that a permanent, military and politically acceptable role for the burgeoning corvette fleet had been found remains a mystery. What is patently clear, however, is that both the British and the Americans considered the NEF a stopgap measure. By the summer of 1941 it was becoming increasingly evident that the U.S. would get involved in the Atlantic battle under the guise of defending the neutrality of the Western Hemisphere. When that happened, the role of the RCN in the Western Atlantic would be governed by the accords of ABC 1.

Whatever the final outcome of NEF, the commitment of the corvette fleet to ocean escort work marked a radical departure from the intended use of such vessels.

April 9, 2019

Canada and the Battle of the Atlantic, part 8 by Alex Funk

Editor’s Note: This series was originally published by Alex Funk on the TimeGhostArmy forums (original URL – https://community.timeghost.tv/t/canada-and-the-battle-of-the-atlantic-part-3/1442).

Sources:

- Far Distant Ships, Joseph Schull, ISBN 10 0773721606 (An official operational account published in 1950, somewhat sensationalist)

[Schull’s book was published in part because the funding for the official history team had been cut and they did not feel that the RCN’s contribution to the Battle of the Atlantic should have no official recognition. It is very much an artifact of its era, and needs to be read that way. A more balanced (and weighty) history didn’t appear until the publication of No Higher Purpose and A Blue Water Navy in 2002, parts 1 and 2 of the Official Operational History of the RCN in WW2, covering 1939-1943 and 1943-1945, respectively.]- North Atlantic Run: the Royal Canadian Navy and the battle for the convoys, Marc Milner, ISBN 10 0802025447 (Written in an attempt to give a more strategic view of Canada’s contribution than Schull’s work, published 1985)

- Reader’s Digest: The Canadians At War: Volumes 1 & 2 ISBN 10 0888501617 (A compilation of articles ranging from personal stories to overviews of Canadian involvement in a particular campaign. Contains excerpts from a number of more obscure Canadian books written after the war, published 1969)

- All photos used exist in the Public Domain and are from the National Archives of Canada, unless otherwise noted in the caption.

I have inserted occasional comments in [square brackets] and links to other sources that do not appear in the original posts. A few minor edits have also been made for clarity.

Earlier parts of this series:

Part 8 — Expansion problems: not enough men for not enough ships

Marc Milner discusses the RCN’s ongoing manning crisis afloat and ashore in North Atlantic Run:

… it was also necessary to find personnel to man new shore establishments. Indeed, by early 1941 the latter took precedence of the needs of the fleet. Although the navy remained committed to increasing the number of escort numbers assigned to its first operational priority, defence of the North Atlantic trade lanes, the gradual extension of the war underlined the paramount need for bases. “Our primary object from the Naval point of view,” a Canadian Chiefs of Staff “appreciation” of May 1941 observed, “must therefore be the extension of existing facilities and the provision of new ones to meet the ever-increasing demands of the British — and perhaps the United States — Naval forces.” The expansion fleet was then only one part of a much larger plan of support for North Atlantic naval operations. Moreover, actual planning for the commissioning and work-up of the new escorts took place as the fleet assumed new and more demanding tasks.

The concern of the Chiefs of Staff for facilities underlined the fact that even by the second winter of the war the navy’s growth was still held in check by enormous shortages. … The Director of Naval Personnel, Captain H.T.W. Grant, informed the council that the RCN needed three hundred RCNVR executive officers — none of whom had yet been enlisted — if the authorized commitments for the following May were to be met. This was no mean task in itself, but the Naval Council noted that the training establishments needed to prepare the men had to be built first. The final twist occurred when the minister advised that the navy must first make steps to acquire the necessary land!

As Nelles later explained in a personal letter to Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the First Sea Lord, the RCN was indeed making bricks without straw. … The primary need was now quantity in all aspects of naval endeavour — manpower, ships, and bases.

With existing training establishments choked and new ones still in the planning stages, the provision of personnel for the expanding fleet posed a serious problem. Urgency was to Canadian planning in late 1940, when it became clear that Britain was involved in what Nelles described as “a Naval crisis equal [to] or greater than that which existed in 1917.”

Hon. Angus L. Macdonald, Minister of National Defence for Naval Services, with senior RCN officers, Commodore H.E. Reid and Rear-Admiral P.W. Nelles, September 1940.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-104112

To help address the RCNVR officer shortage, a deal was agreed between the RCN and the RN by which RCNVR officers-in-training would travel to England and receive training at HMS King Alfred, the reservist training centre at Hove:

The great irony of the scheme was that it proved virtually impossible to draw on this body of highly trained Canadian naval officers later on, when the RCN was badly in need of qualified personnel. Certainly the King Alfred plan did nothing to resolve the shortage of qualified officers that crippled the fleet in 1941.

Another aspect of proper planning was work-up and operational training facilities for the fleet, particularly with respect to ASW.

Especially considering numerous British complaints of the low quality of Canadian ASW efforts on destroyers operating from UK bases. Canada had possessed no submarines since 1922 and had long since lost the ability to operate them. There was one submarine operating with the RN’s Third Battle Squadron out of Halifax: the Dutch O-15:

At the end of November, the Naval Staff formally requested that O-15 be made available for A/S training. For the moment, the Admiralty refused, although some exercises were conducted with her later in the year.

[Editor’s Note: The Dutch Submarines page on O-15 says “… the RCN was so desperate for ASW training in 1940 that when a Dutch submarine, which had avoided capture when Holland was invaded, fetched up in Halifax en route to England, the navy used it without permission and would not let it go when the Admiralty asked them to relinquish her …”]

Unable to obtain satisfaction from British sources, the RCN turned to the US, where preliminary investigations into acquiring an older USN submarine were made in early 1941. Commodore H.E. Reid, the naval attaché in Washington, raised the matter with the new Permanent Joint US-Canadian Board of Defense and then set about beating the bushes in more obscure parts of the American capital. By the end of January it was clear there were no submarines of any description would be forthcoming from American sources. The only gesture of assistance that the USN made was an offer to send a squadron of submarines (four boats) on a courtesy visit sometime in the summer. The RCN was advised to prepare itself to make maximum use of two to three weeks of free ASDIC training time. It was a generous offer, but it did not provide the RCN with a long-term solution to the pressing problem of providing ASDIC trainees with proper targets. Probably for this reason and because of the fear that acceptance would prejudice negotiations still underway regarding the future of O-15, the RCN politely declined the American offer. A few days later the Admiralty signalled its consent to the use of O-15 for A/S training.

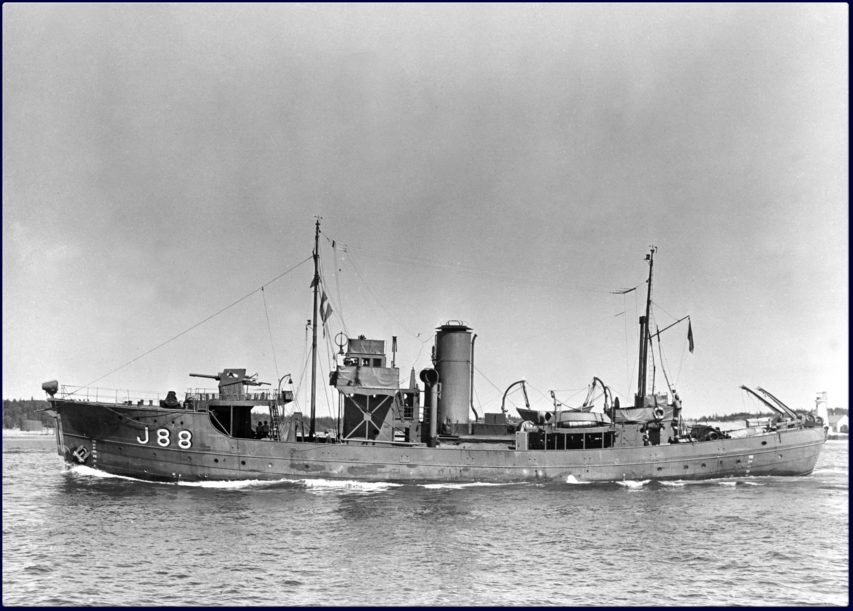

View from HMCS ST Laurent of the submarine O-15 of the Royal Netherlands Navy during an anti-submarine training exercise off Pictou, Nova Scotia, Canada, 20 August 1941.

Canada. Dept. of National Defence / Library and Archives Canada / PA-105491

While extremely useful, one submarine was not sufficient for all training needs and the shortage would continue until 1943 when Italian and Free French submarines became available in the Western Atlantic to help train US-built British destroyer escorts commissioning from US ports.

… having secured the services of O-15, there was no reason not to return to the American offer of training time on US submarines. That the RCN saw fit to reject direct USN assistance was the first sign of what became a curious, closely guarded attitude on the part of the RCN towards the USN. Nor were training submarines the only answer to preparing escorts for battle with the U-boats. Had the RCN — and the RN, for that matter — been more attuned to developments in the war at sea and seen the U-boat pack for what it really was, a flotilla of submersible torpedo boats, motor launches would have formed an essential part of A/S training as well. These small craft offered an excellent substitute for a training submarine in exercises designed to simulate night attacks on convoys, but it was not until 1942 that the RCN would begin to use launches for that purpose. The continuing fixation with submerged targets was understandable, since training on an actual submarine was the only means of attaining and maintaining efficiency among ASDIC operators. …

Aside from the escorts operating from the UK, RCN expansion hung fire during the winter of 1940-1. Obviously it would have been better to commission twenty corvettes into the RCN during 1940, as the Staff had originally planned. But when winter closed its icy grip on the St. Lawrence River, only four were operational.

A few more ships were patrolling and training in Pacific waters, and they would be joined by fresh ships commissioned on the west coast from British Columbian yards over the winter (six ships all told). The last week of April brought the thaw, and with spring came the expected deluge of new ships. Orillia, Pictou, and Rimouski were down the river before the month ended. In May, ten more were accepted into service, three for the west, six for the east. (Including HMCS Baddeck, the ship that Captain Alan Easton, whose firsthand account I find quite fascinating, first commanded.)

In a period of seven months thirty-three warships were added to the Navy List, slightly over half of the 1939-40 construction program.

Had it been possible to build the fleet entirely on the Atlantic or Pacific coasts, the seasonal character of expansion would have been averted. But because of the heavy demand for repair work on east coast yards after the fall of France only three orders for corvettes were ever placed east of the St. Lawrence River. [All at Saint John Shipbuilding.] All of these were much delayed, and the last to commission, Moncton not taken into service until April 1942 — two full years after the commencement of the program.

Lieutenant-Commander Easton described his first look at and first voyage of the Baddeck in 50 North: Canada’s Atlantic Battleground:

She was resting on the blocks of a dry-dock in a shipyard farther up the [St. Lawrence] river when I first saw her. I had stood on the wall and looked down at her sturdy features, the brand new vessel which was to take me many miles over the ocean. HMCS Baddeck was mine; we were to share at least a part of our lives together.

I was elated at being given command. I could not thank anybody because the news came in a naval signal, one of those pieces of paper rather like a telegram, but without the advertising at the top. I just had time to catch the night train from Halifax to Quebec.

When anyone is given an appointment which places him in charge of something which he thinks is pretty important, it generally makes him feel he has been singled out as being above the crowd. But this was not so in my case; the authorities who selected me probably had no alternative. There was no one else handy. In the Royal Canadian Navy during the first half of the war, there were not enough people to go round. Often you got the job whether you deserved it or not.

I could see now that the ship had been built mainly after the fashion of a big steam trawler, but with a longer and sharper bow. From drawings I had seen I knew she was 204 feet long and had a thirty-three-foot beam. Her appearance fitted these dimentions and in her nakedness her fat belly seemed to bulge over the floor of the dry dock, suggesting an ample capacity for, among other things, a large engine. Her rounded stern was inclined to turn up like a duck’s tail.

[…]

The first sight of a ship in which one is going to sail is always exciting, that first intensely interesting glimpse which creates an immediate impression — sometimes of disappointment. […] This time I was not disappointed. And as I stood on her deck, I felt alone with her in the silence of the deserted yard. It was Sunday and everything was quiet — no hammering or riveting, no trail of steam drifting up from the machine shop. Would she stay young like this or grow old quickly? I was glad it was quiet because this was my private introduction and she would try to show me herself — before our exploits began.

Exploits? That was the trouble. She might never be involved in a fight. A corvette, after all, was designed for coastal patrol work. And Canada had a long coastline. The war was on the other side of the Atlantic.

It was a month or more before I had an opportunity to try out her promises of performance on the broad reaches of the St. Lawrence below Quebec. She had been fitted out, her crew had come on board and she had been duly commissioned into the Royal Canadian Navy.