Ultimate Restorations

Published on 20 Aug 2012http://ultimaterestorations.com See how the boiler of a steam locomotive works. Ultimate Restorations is the hit show that airs on public television across America.

June 30, 2018

Animation of How a Steam Locomotive’s Boiler Works

September 24, 2017

GE Steam Turbine Locomotives – 1938 Educational Documentary – WDTVLIVE42

Published on 30 May 2017

The General Electric steam turbine locomotives were two steam turbine locomotives built by General Electric (GE) for Union Pacific (UP) in 1938. This newsreel style promotional film shows construction of the locomotives while highlighting their expected capabilities.

September 6, 2017

Grand Trunk Pacific Transcontinental Railway Construction – circa 1910 Documentary – WDTVLIVE42

Published on 26 Mar 2017

The Grand Trunk Pacific Railway was a historical Canadian transcontinental railway running from Winnipeg to the Pacific coast at Prince Rupert, British Columbia. East of Winnipeg the line continued as the National Transcontinental Railway, running across northern Ontario and Quebec, crossing the St. Lawrence River at Quebec City and ending at Moncton, New Brunswick. The entire line was managed and operated by Grand Trunk Railway. Construction of this transcontinental railway began in 1905 and was completed by 1913.

Scenes show earthworks and removal of spoil via railway carriages, steam locomotives hauling flatcars, sleepers being unloaded from trains and position on the new roadbed, unloading of rails, fastening of rails to sleepers, and the works train travelling over the newly completed trackwork.

WDTVLIVE42 – Transport, technology, and general interest movies from the past – newsreels, documentaries & publicity films from my archives.

#trains #locomotive #railways #wdtvlive42

May 6, 2017

History of the Royal Navy – Steam, steel and Dreadnoughts (1806-1918)

Published on 1 Mar 2013

Here’s also an older post covering the technological challenges faced by the Royal Navy in the post-Napoleonic era, and some of the reasons for all those “weird” ship designs in the Victorian era.

March 12, 2017

Reasons for THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Published on 26 Feb 2015

The Industrial Revolution transformed and shaped our modern world as we know it. Why did the fundamental changes of the Industrial Revolution begin in Great Britain? In our first episode about the era of Industrial Revolution, Brett explains how the agricultural revolution, a few inventions in the textile industry, the steam machine, improving means of transport and an overall changing society created a solid basis for the coming changes of the late 18th century.

February 16, 2017

60163 Tornado Settle to Carlisle 14th Feb 2017

Published on 14 Feb 2017

BBC News report on 60163 Tornado’s run on the Settle to Carlisle line this morning, the first Steam Loco to do the service run in nearly 50 years.

H/T to Jim Guthrie for the link.

January 21, 2017

QotD: 1815’s other triumph

[In] 1815, George Stephenson, a humble, self-taught engine-wright with an impenetrable Geordie accent (to which he probably gave the name), put together all the key inventions that — at last — made steam locomotion practicable: the smooth wheels, counter-intuitively less likely to slip if heavily laden; the steam-blast into the chimney to accelerate the draught over the coals; the vertical cylinders connecting directly with the wheels; the connecting rods between the wheels. A year later came his redesign of rails themselves, then later his multi-tubular boiler.

As his biographer, Samuel Smiles, put it:

“Thus, in the year 1815, Mr Stephenson, by dint of patient and persevering labour … had succeeded in manufacturing an engine which … as a mechanical contrivance, contained the germ of all that has since been effected. It may in fact be regarded as the type of the present locomotive engine.”

Suddenly the movement of goods and people fast and cheaply over long distances became possible for the first time.

Not content with that, in 1815 Stephenson also invented the miner’s safety lamp (though snobbish London grandees, unable to conceive that such a humble man could have done so, gave and have continued to this day to give the credit to Sir Humphry Davy). The year of Waterloo was an annus mirabilis of the industrial revolution, putting Britain on course to dominate and transform the world, whether we beat Boney or not. Steam, followed by its offspring internal combustion and electricity, would catapult humankind into prosperity.

Incidentally, there is a tenuous connection between Napoleon and Stephenson. If Bonaparte’s conquests and the corn laws had not driven up the price of corn, then horse feed would have been cheaper and the coal owners who employed Stephenson would not have risked so much money in letting him build a machine to try to find a less expensive way to pull wagons of coals from the pithead in Killingworth to the staithes on the Tyne.

Matt Ridley, “Waterloo or railways”, Matt Ridley Online, 2015-06-18.

October 20, 2016

Sea power and land power

At Samizdata, Brian Micklethwait has an interesting essay, including this discussion of the historical differences between naval and land powers (Athens and Sparta, Greece and Persia, Britain and France, etc.) and an insight into the odd growth pattern of the British empire after the introduction of steam power:

This contrast, between seafaring and land-based powers, has dominated political and military history, both ancient and modern. Conflicts like that between Athens and Sparta, and then between all of Greece and Persia, and the later conflicts between the British – before, during and since the time of the British Empire – and the succession of land-based continental powers whom we British have quarrelled with over the centuries, have shaped the entire world. Such differences in political mentality continue to matter a lot.

Throughout most of modern human history, despots could completely command the land, including all inland waterways. but they could not command the oceans nearly so completely. Wherever the resources found in the oceans or out there beyond them loomed large in the life and the economy of a country or empire, there was likely to be a certain sort of political atmosphere. In places where the land and its productivity counted for pretty much everything, and where all communications were land-based, a very different political atmosphere prevailed.

You see this contrast in the difficulties that Napoleon had when squaring up to the British, and to the British Royal Navy. Napoleon planned his land campaigns in minute detail, like a chess grandmaster, and he played most of his military chess games on a board that could be depended on to behave itself. But you couldn’t plan a sea-based campaign in this way, because the sea had a mind of its own. You couldn’t march ships across the sea the way you can march men across a parade ground, or a continent. At sea, the man on the spot had to be allowed to improvise, to have a mind of his own. He had to be able to exercise initiative, in accordance with overall strategic guidance, yes, but based on his own understanding of the particular circumstances he faced. There was no tyranny like that of the captain of a ship, when it was at sea. But sea-based powers had many ships, so navies (particularly merchant navies), by their nature dispersed power. In a true political tyranny, there can be only one tyrant.

More fundamentally, the sea provided freedom, because it provided an abundance of places to escape to, should the tyranny of a would-be tyrant become too irksome and life-threatening. Coastal communities had other sources of wealth and power besides those derived from inland, and could hide in their boats from tyrants. Drive a sea captain and his crew mad with hatred for you and for your tyrannical commands and demands, and he and his ship might just disappear over the horizon and never be seen again. Good luck trying to capture him. If you did seriously attempt this, you would need other equally strong-minded and improvisationally adept sea captains whom you had managed to keep on your side, willing to do your bidding even when they were far beyond the reach of your direct power. One way or another, your tyranny ebbed away.

Other kinds of tyranny, or the more puritanical sort, were also typically made a nonsense of by seagoing folk, whenever they enjoyed a spot of shore leave.

[…]

The development of mechanically powered ships, since Napoleon’s time, served to make the deployment of ships at sea a lot more like marching them about on a parade ground. First, the significance of the wind and its often unpredictable direction is pretty much negated. And mechanically powered ships are also, especially in the days of coal power, much more dependent upon land-based installations, the arrangement of which demanded Napoleonic logistical virtuosity. Much of late British imperial politics only makes sense if you factor in the compelling need for coaling stations to feed ships. Sailing ships don’t run out of fuel. Modern ships do.

December 10, 2015

Your business model and transformative change

At The Arts Mechanical, there’s a paean to the amazing technological achievement represented by this steam engine:

… and a return to reality by looking at how that amazing steam engine was made utterly obsolete by a humble diesel switcher and its direct descendants:

Which brings us to the picture at the head of this post. Anybody ever hear of Lima Locomotive? Here is what they did. That is a C&O RR H8 Allegheny. It is the largest and most powerful steam locomotive ever built. The locomotive was in the shed and there was no way I could get a side shot but the size of it boggles the mind. The firebox is the same size as a small house. The locomotive was designed to move mountains of coal and that’s what it did.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2-6-6-6

It was also obsolete before it was erected.

May 22, 2015

The trains of war – the military application of steam power

James Simpson on the revolution in military affairs triggered by the development of the steam engine and the railways:

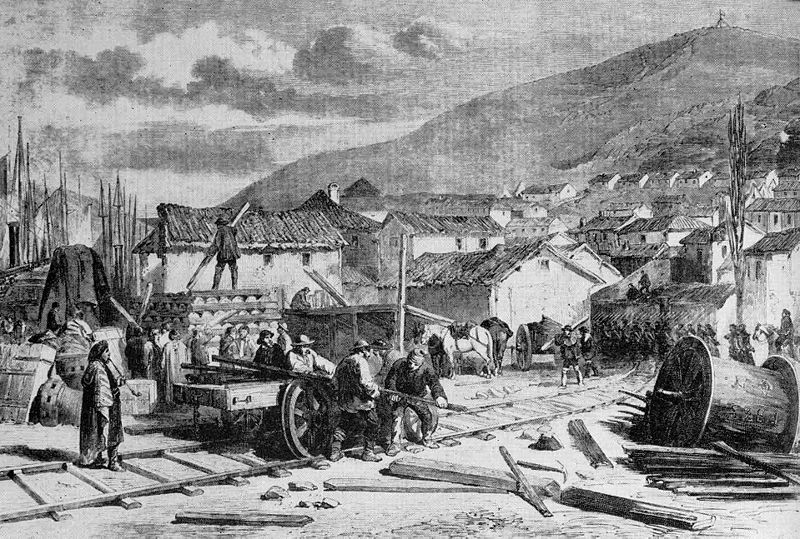

Navvies working on the Grand Crimean Central Railway, 1854. Charles Walker: Thomas Brassey, Railway Builder, 1969. (via Wikipedia)

Trains were cutting-edge weapons of war in the 19th century — and all the major powers were figuring out how to deploy them. The Europeans learned how to move troops by train. The Americans — how to fight on rail cars. The British, meanwhile, found they could dominate an empire from the tracks.

In today’s world of tanks, bombers and submarines, it’s perhaps hard to believe that the train was once an amazingly mobile weapons platform. They might be locked to their rails, but for over a century trains were the fastest means of hauling troops and artillery to front lines across the world.

The invention of the railway shaped warfare for a century. Rails allowed force projection across immense distances — and at speeds which were impossible on foot or by horse.

[…]

The first demonstration of the military efficacy of the railroads was the 1846 Polish Uprising. Prussia rushed 12,000 troops of the Sixth Army Corps, with guns and horses, to the Free City of Krakow to help put down the Polish rebellion. In this period of nationalist uprisings, Russia and Austria also used their railroads against similar uprisings from 1848 to 1850.

A lack of infrastructure and experience stifled the success of these early endeavors. Due to a lack of rolling stock, suitable platforms and double-track stretches, the trains sometimes operated far slower than a man could march on foot.

Austria was first to get it right. In 1851, the Austrian Empire shuttled 145,000 men, nearly 2,000 horses, 48 artillery pieces and 464 vehicles over 187 miles.

March 23, 2015

Changing Times – Railroads & Canals I IT’S HISTORY

Published on 10 Mar 2015

It certainly is no big deal to have a small cruise along the canals or ride a train. But what is essential infrastructure today had to be invented out of necessity in the late 18th and early 19th century. In our new episode Brett tells you everything about canals and railways and how they changed the way we transport things.

December 20, 2014

QotD: When it’s steam engine time

Ridcully poked at his pipe with a pipe cleaner and said, “Ye-es, that is a conundrum. Surely the steam engine cannot happen before it’s steam-engine time? If you saw a pig, you would, I think, say to yourself, well, here’s a pig, so it must be time for pigs. You wouldn’t question its right to be there would you?”

“Certainly not,” said Lu-Tze. “In any case, pork gives me the wind something dreadful. What we know is that the universe is never-ending story that, happily, writes itself continuously. The trouble with my brethren in Oi Dong is that they are fixated on the belief that the universe can be totally understood, in every particular jot and tittle.”

Ridcully burst out laughing. “Oh, my word! You know, my wonderful associate Mister Ponder Stibbins appears to have fallen into the same misapprehension. It seems that even the very wise have neglected to take notice of one rather important goddess … Pippina, the lady with the Apple of Discord. She knows that the universe, while it requires rules and stability, also needs just a tincture of chaos, the unexpected, the surprising. Otherwise it would be a mechanism — a wonderful mechanism, ticking away the centuries, but with nothing different happening. And so we may assume that the loss of balance will be allowed this time and the beneficent lady will decree that this mechanism might yield wonderful things, given a chance.”

“For my part, I would like to give it a chance,” said Lu-Tze. “Serendipity is no stranger to me. I know the monks have been carefully shepherding the world, but I rather think they don’t realize that the sheep sometimes have better ideas. Uncertainty is always uncertain, but the difficulty with people who rely on systems is that they begin to believe that nearly everything is in some way a system and therefore, sooner or later, they become bureaucrats.”

Terry Pratchett, Raising Steam, 2013.

December 7, 2014

Kings Cross, 1956

Published on 26 Mar 2013

London’s King’s Cross station in the age of steam. Soon diesels would replace steam power and Mr Hammond, General Manager of British Railways Eastern Region, explains how he will reduce his fleet of locomotives by a factor of four. You can also learn how to swing a buckeye coupler. They are very heavy, but the shunter in this film makes it look easy.

June 20, 2014

British steam locomotives

H/T to Jon, my former virtual landlord, for the link.

June 2, 2014

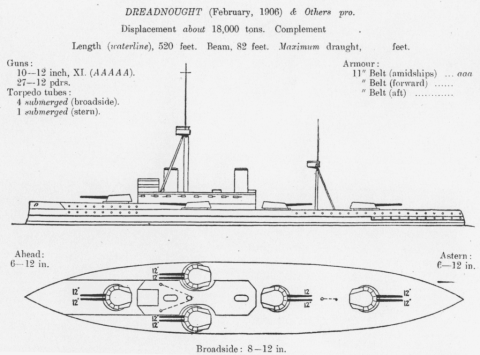

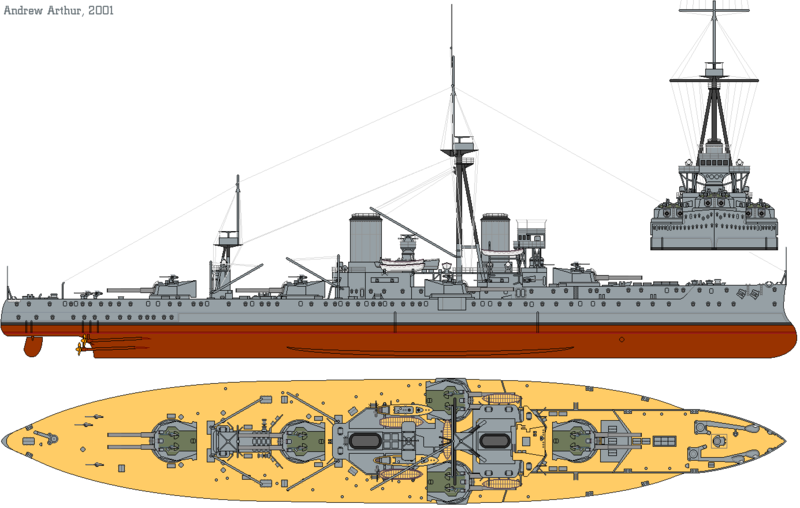

The naval revolution and HMS Dreadnought

BBC News Magazine looks back on the launch of the first modern all-big-gun battleship, HMS Dreadnought, in 1906.

[HMS Dreadnought] “really transformed naval warfare rather like the tank did on land warfare. In fact Dreadnought was described at the time as ‘the most deadly fighting machine ever launched in the history of the world'”.

Dreadnought brought together for the first time a series of technologies which had been developing over several years. Most important was her firepower. She was the first all big-gun battleship — with ten 12-inch guns. Each gun fired half-ton shells over 4ft tall and packed with high explosive. They weighed as much as a small car. Standing next to one today, it is easy to see how a single broadside could destroy an opponent — and do so at 10 miles’ distance.

These great distances caused problems of their own — in controlling and directing the fire — and Dreadnought was one of the first ships fitted with new equipment to electrically transmit information to the gun turrets.

For potential enemies on the receiving end this was a terrifying prospect. Admiral Lord West, a former head of the Royal Navy, calls Dreadnought “a most devastating weapon of war, the most powerful thing in the world”.

Potential adversaries would also have trouble outrunning her. New steam turbine engines gave her a maximum speed of about 25mph. They made her more reliable than previous ships, and able to sustain a higher speed for much longer.

But there was something else, too. Dreadnought had been built in just one year — a demonstration of British military-industrial might at a time when major battleships generally took several years to build. This, says Roberts, was an “enormous achievement which made the Germans sit up because their shipbuilding capability just could not match that”.

Despite the Royal Navy’s reputation for being tradition-bound and stodgy, they had quite an interesting history of experimentation and innovation in ship design. The launch of HMS Dreadnought was a good example of the navy being willing to take risks — specifically the risk of making the rest of the battlefleet obsolete overnight.

Update, 18 February, 2018: A recent post at Naval Gazing provides more information on the evolution of the Dreadnought design.

[Admiral Sir John “Jackie”] Fisher established a committee, including John Jellicoe and Reginald Bacon, who settled on the characteristics that would define Dreadnought. Bacon, later Dreadnought’s first captain – regarded by Fisher as “the cleverest officer in the Navy” – was the man who convinced Fisher to switch from all-10″ to all-12″. Reports of the effectiveness of the 12″ gun during the Russo-Japanese war helped confirmed this decision.

The second major change that Dreadnought brought is less obvious but in many ways more important. Dreadnought was the first large warship to use steam turbines instead of reciprocating engines. This increased her speed from the previous standard of 18 kts to 21 kts, saved 1000 tons, and most importantly allowed her to maintain high speed for much longer without the risk of mechanical failure. This was a vital component of Fisher’s other innovation, what we now call net-centric warfare. The high sustained speed of the new ships allowed them to cover greater areas, based on the improved information gathering and dissemination system that Fisher set up.

Dreadnought broke new ground in other areas, too. Her hull was about 18% lighter by volume than that of the proceeding Lord Nelson class, and she set a new standard for watertight integrity, removing most doors below the waterline. The only area without major improvement was armor, which was actually slightly less than in the Lord Nelson.

The design process began in November of 1905, initially with plans for 6 turrets. The first set of designs included the obvious (a hexagonal layout), the slightly less obvious (three superfiring turrets on each end) and the weird (a triangle at each end, with two turrets abreast and a superfiring turret above them). Eventually, it was decided that muzzle blast made the later two designs infeasible. Blast interference between the wing turrets meant that the aft pair was replaced by a single centerline turret, producing the arrangement used in Dreadnought.

The final result was a ship of 18,000 tons and 527 ft. With an 8-gun broadside, she matched the long-range firepower of almost any two ship afloat, and she set a new standard for speed in battleships. She was laid down on October 2nd, 1905, and launched only 5 months later, on February 10th, 1905. The 14 months exactly from laying down to commissioning set a record that has never been broken for capital ships, and was intended by Fisher to send a message to the world.

He also references the Dreadnought Hoax, which I’d never heard of … I’m surprised Cole wasn’t prosecuted as a spy, given the popular anxieties about foreign espionage and worries about an invasion.