Army University Press

Published 29 Jul 2022This film examines the Chinese military. Subject matter experts discuss Chinese history, current affairs, and military doctrine. Topics range from Mao, to the PLA, to current advances in military technologies. “Near Peer: China” is the first film in a four-part series exploring America’s global competitors.

(more…)

November 28, 2022

Near Peer: China (Understanding the Chinese Military)

October 8, 2021

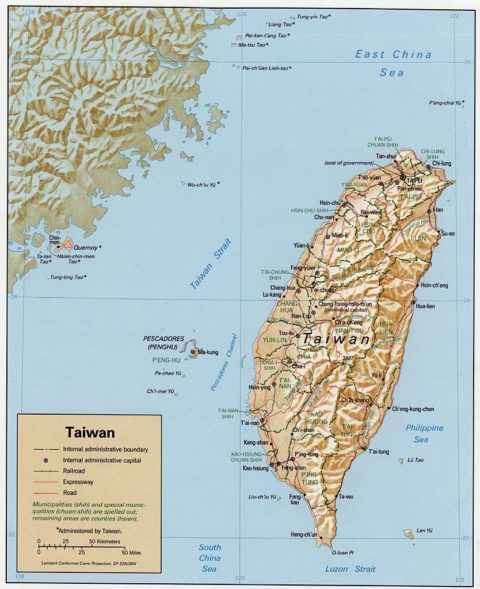

The case for defending Taiwan

Roberto White explains why the west should help protect the Republic of China from the People’s Republic of China:

The past few days have seen Taiwan subjected to another wave of continuous harassment by China. Of course this is nothing new; China has violated Taiwan’s airspace since at least 2014. But, on Monday, a record 34 fighter jets were dispatched to Taiwan. Beijing’s increasingly erratic behaviour towards Taiwan brings to the fore why the West must defend them.

Taiwan is a free-market democracy that, despite its overbearing northern neighbour, has managed to create a vibrant economy that ranks as the sixth freest economy in the world. Crucially, it is a major producer of semiconductors (a device that helps power everything from cars to satellites), accounting for 92 per cent of all production of the world’s most sophisticated and important chips. Thus, from both an ideological and strategic standpoint, defending Taiwan is a mutually beneficial move.

The case for Taiwan’s defence is further strengthened when we look at what could happen in Asia should China take Taiwan by force.

With Taiwan’s ports and air bases, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) could extend its maritime militia northwards through the Ryukyu (the chain of islands between Taiwan and Japan) and the Senkaku Islands (disputed by China and Japan). This would give China increased leverage over Japan in a time of crisis by, for example, restricting its maritime commerce.

The CCP could further use Taiwan as a base for tighter control of the South China Sea by blocking the Luzon Strait (between Taiwan and the Philippines) and the Balintang channel, which would cut off the traditional route used by the US Navy to navigate regional waters. In essence, China would immediately become the foremost power in the Indo-Pacific that could eventually kick the US and its allies out of the region. Unfortunately, the threat of a Chinese invasion is not a distant reality. In March of this year Admiral Philip Davidson, the United States’ top military officer in the Asia-Pacific, warned that China could invade Taiwan by 2027.

Given the perilous scenario that would emerge from a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, it is vital that, should an invasion happen, the West comes to Taiwan’s defence. However, until such a time, Western allies should aim to help Taiwan by promoting its participation in international forums. The first step would be to allow diplomats and other officials with Taiwanese passports to enter UN buildings, which they currently cannot do. This would most likely provoke a backlash from China, yet it would also confer Taiwan the dignity and respect that officials from every other state have.

The West should also stand firm against Chinese attempts to exclude Taiwan from international organisations. Between 2008-2016, Taiwan was invited to be an observer at the World Health Organization (WHO) under the name “Chinese Taipei”. In 2016, after Tsai Ing-Wen was elected Taiwan’s President, Beijing rescinded the invitation and Taiwan has not been allowed to participate since.

July 6, 2020

Cold War Two is upon us, but it’s not all Trump’s fault (believe it or not)

Niall Ferguson on the rapid drop in temperature in US/Chinese relations in the last eight years:

President Donald Trump and PRC President Xi Jinping at the G20 Japan Summit in Osaka, 29 June, 2019.

Cropped from an official White House photo by Shealah Craighead via Wikimedia Commons.

“We are in the foothills of a Cold War.” Those were the words of Henry Kissinger when I interviewed him at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Beijing last November.

The observation in itself was not wholly startling. It had seemed obvious to me since early last year that a new Cold War — between the U.S. and China — had begun. This insight wasn’t just based on interviews with elder statesmen. Counterintuitive as it may seem, I had picked up the idea from binge-reading Chinese science fiction.

First, the history. What had started out in early 2018 as a trade war over tariffs and intellectual property theft had by the end of the year metamorphosed into a technology war over the global dominance of the Chinese company Huawei Technologies Co. in 5G network telecommunications; an ideological confrontation in response to Beijing’s treatment of the Uighur minority in China’s Xinjiang region and the pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong; and an escalation of old frictions over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

Nevertheless, for Kissinger, of all people, to acknowledge that we were in the opening phase of Cold War II was remarkable.

Since his first secret visit to Beijing in 1971, Kissinger has been the master-builder of that policy of U.S.-Chinese engagement which, for 45 years, was a leitmotif of U.S. foreign policy. It fundamentally altered the balance of power at the mid-point of the Cold War, to the disadvantage of the Soviet Union. It created the geopolitical conditions for China’s industrial revolution, the biggest and fastest in history. And it led, after China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, to that extraordinary financial symbiosis which Moritz Schularick and I christened “Chimerica” in 2007.

How did relations between Beijing and Washington sour so quickly that even Kissinger now speaks of Cold War?

The conventional answer to that question is that President Donald Trump has swung like a wrecking ball into the “liberal international order” and that Cold War II is only one of the adverse consequences of his “America First” strategy.

Yet that view attaches too much importance to the change in U.S. foreign policy since 2016, and not enough to the change in Chinese foreign policy that came four years earlier, when Xi Jinping became general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party. Future historians will discern that the decline and fall of Chimerica began in the wake of the global financial crisis, as a new Chinese leader drew the conclusion that there was no longer any need to hide the light of China’s ambition under the bushel that Deng Xiaoping had famously recommended.

October 31, 2019

“Big Lizzie” (HMS Queen Elizabeth) to sail into disputed waters in 2021

UK Defence Journal reported a few days back that the Royal Navy’s new aircraft carrier will take on her first active deployment in 2021, including a possible Freedom of Navigation exercise (FONOPS) in the South China Sea:

Aerial view of HMS Queen Elizabeth with Type 23 frigates HMS Iron Duke (centre) and HMS Sutherland (right) in June 2017 off the coast of Scotland.

Photo by MOD via Wikimedia Commons.

Commodore Michael Utley, Commander United Kingdom Carrier Strike Group, is reported by Save The Royal Navy here as saying that HMS Queen Elizabeth will be escorted by two Type 45 destroyers, two Type 23 frigates, a nuclear submarine, a Tide-class tanker and RFA Fort Victoria.

The ship will also carry 24 F-35B jets, including US Marine Corps aircraft, in addition to a number of helicopters.

Prior to the deployment, it is understood that the Queen Elizabeth carrier strike group will go through a work-up trial off the west Hebrides range sometime in early 2021.

When asked about whether or not the UK has enough escorts to do this without impacting other commitment, Defence Secretary Ben Wallace said:

The size and the scale of the escort depends on the deployments and the task that the carrier is involved in. If it is a NATO tasking in the north Atlantic, for example, you would expect an international contribution to those types of taskings, in the same way as we sometimes escort the French carrier or American carriers to make up that.

It is definitely our intention, though, that the carrier strike group will be able to be a wholly UK sovereign deployable group. Now, it is probably not necessary to do that every single time we do it, depending on the tasking, but we want to do that and test doing it. Once we have done that, depending on the deployment, of course, we will cut our cloth as required.

Gareth Corfield expands on this in The Register:

Although the initial plan was for Britain’s biggest ever warship to sail through the South China Sea, which China claims as its own territory in defiance of international laws and norms, and despite claims from at least six other countries including Vietnam and the Philippines, this detail was noticeably absent from the UKDJ report.

Over 200 islands, also subject to disputes between China, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and the Philippines, also lie in the area, which stretches across 3.5 million square kilometres and is visited by one-third of the world’s shipping traffic.

A US presence on the South China Sea deployment will be a useful political tool for the administration as a show of strength to China as well as asserting the right to freedom of navigation in the sea. In addition, it reinforces the idea that the UK supports US foreign policy – Queen Elizabeth is effectively replacing a US carrier on her Far Eastern tour as part of the superpower’s standing naval presence.

Of the jets aboard QE, around half will be supplied by the US Marine Corps, as has been reported for years.

The Dutch Navy will definitely join the deployment, most likely with a De Zeven Provinciën-class frigate – replacing one of the British Type 23 frigates in the mooted carrier battle group. Similarly, UKDJ reckons that an American destroyer will join the 2021 deployment (named Carrier Strike Group 21), freeing up a British Type 45 destroyer.

Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth (R08) underway in the Atlantic on 17 October 2019, participating in exercise “WESTLANT 19”. The first operational deployment for HMS Queen Elizabeth with No. 617 Squadron and a squadron of USMC Lockheed Martin F-35B Lightnings is planned for 2021.

Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Nathan T. Beard, US Navy, via Wikimedia Commons

February 15, 2018

HMS Sutherland to conduct Freedom of Navigation exercise (FONOPS) in the South China Sea

Gareth Corfield on the current voyage of the Royal Navy frigate HMS Sutherland (F81):

HMS Sutherland (F81), a Type 23 frigate of the Royal Navy

Photo by Vicki Benwell, RN and released by the Ministry of Defence.

A British warship has set sail for the South China Sea, paving the way for aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth to do the same thing in three years’ time.

HMS Sutherland, a Type 23 frigate, will sail through the disputed region on her way home from Australia, as much to fly the flag in foreign climes as to carry out a dry run ahead of the nation’s flagship doing the same thing in 2021.

The South China Sea is one of the world’s naval choke points. Very high values of trade (the total value was estimated by the Daily Telegraph as £3.8tn) either originates in or passes through the sea. The region is under dispute chiefly because of China, which is trying to extend its territorial limits (and thus the area it can directly control) by building artificial islands to embiggen its borders.

Sutherland will be carrying out a freedom of navigation exercise, which is where a warship sails through a disputed bit of sea to send the message “you can’t stop us doing this”. The idea is to reinforce the notion that international waters, where anyone has right of free passage, can’t be unilaterally claimed by one country.

January 9, 2014

China asserts “police powers” over most of the South China Sea

James R. Holmes on the change in China’s approach to the disputed South China Sea region:

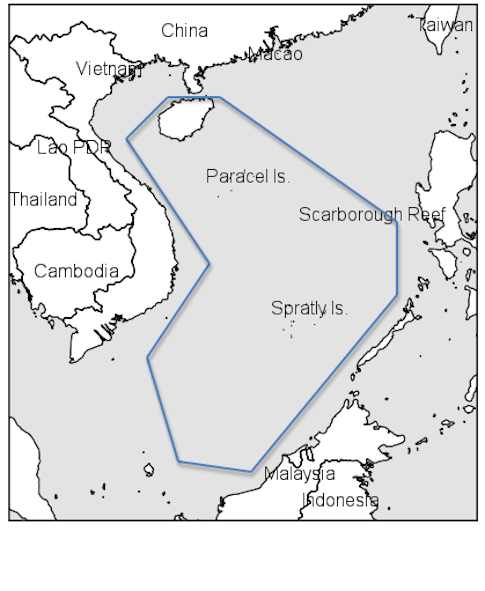

Associated Press reporter Christopher Bodeen chooses his words well in a story on China’s latest bid to rule offshore waters. Beijing, he writes, is augmenting its “police powers” in the South China Sea. That’s legalese for enforcing domestic law within certain lines inscribed on the map, or in this case nautical chart.

The Hainan provincial legislature, that is, issued a directive last November requiring foreign fishermen to obtain permission before plying their trade within some two-thirds of the sea. Bill Gertz of the Washington Free Beacon supplies a map depicting the affected zone. It’s worth pointing out that the zone doesn’t span the entire waterspace within the nine-dashed line, where Beijing asserts “indisputable sovereignty.”

China imposes fishing curbs: New regulations imposed Jan. 1 limit all foreign vessels from fishing in a zone covering two-thirds of the South China Sea. Washington Free Beacon

A few quick thoughts as this story develops. One, regional and extraregional observers shouldn’t be too shocked at this turn of events. China’s claims to the South China Sea reach back decades. The map bearing the nine-dashed line, for instance, predates the founding of the People’s Republic of China. It may go back a century. Nor are these idle fancies. Chinese forces pummeled a South Vietnamese flotilla in the Paracels in 1974. Sporadic encounters with neighboring maritime forces — sometime violent, more often not — have continued to this day. (See Shoal, Scarborough.) Only the pace has quickened.

Henry Kissinger notes that custodians and beneficiaries of the status quo find it hard to believe that revolutionaries really want what they say they want. Memo to Manila, Hanoi & Co.: Beijing really wants what it says it wants.

October 27, 2013

“Dangerous Ground” in the South China Sea

John Donovan linked to this interesting New York Times Magazine feature about the Spratly Islands and the geopolitical standoff between China and pretty much all of the other nations bordering the South China Sea:

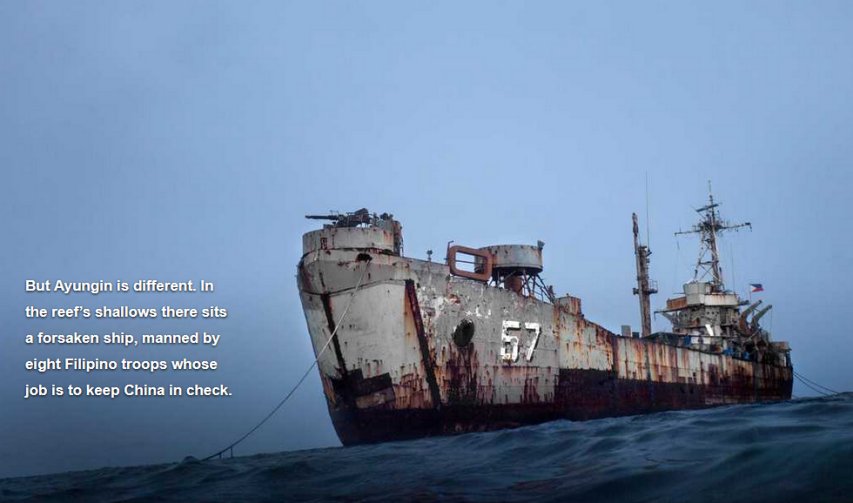

Ayungin Shoal lies 105 nautical miles from the Philippines. There’s little to commend the spot, apart from its plentiful fish and safe harbor — except that Ayungin sits at the southwestern edge of an area called Reed Bank, which is rumored to contain vast reserves of oil and natural gas. And also that it is home to a World War II-era ship called the Sierra Madre, which the Philippine government ran aground on the reef in 1999 and has since maintained as a kind of post-apocalyptic military garrison, the small detachment of Filipino troops stationed there struggling to survive extreme mental and physical desolation. Of all places, the scorched shell of the Sierra Madre has become an unlikely battleground in a geopolitical struggle that will shape the future of the South China Sea and, to some extent, the rest of the world.

[…]

To understand how Ayungin (known to the Western world as Second Thomas Shoal) could become contested ground is to confront, in miniature, both the rise of China and the potential future of U.S. foreign policy. It is also to enter into a morass of competing historical, territorial and even moral claims in an area where defining what is true or fair may be no easier than it has proved to be in the Middle East.

The Spratly Islands sprawl over roughly 160,000 square miles in the waters of the coasts of the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, Taiwan and China — all of whom claim part of the islands.

September 10, 2013

China’s historical model for naval strategy

At The Diplomat, James Holmes explains the odd fact that China is a “good citizen” in their coalition work with other countries fighting piracy away from home, but bullies its neighbours in the waters closer to home:

The analogy is the doctrine of “no peace beyond the line” practiced in late Renaissance Europe. To recap: in a nifty bit of collective doublethink, European rulers struck up a compact whereby nations could remain at peace in Europe, avoiding the hardships of direct conflict, while assailing each other mercilessly beyond a mythical boundary separating Europe from the Americas. In practice this meant they raided each other’s shipping and outposts in the greater Caribbean Sea and its Atlantic approaches.

It feels as though an inverse dynamic is at work in the Indo-Pacific theater. Naval powers cooperate westward of the line traced by the Malay Peninsula, Strait of Malacca, and Indonesian archipelago. Suspicions pockmarked by occasional confrontation predominate east of the South China Sea rim, a physical — rather than imaginary — line dividing over there from home ground.

A non-Renaissance European, Clausewitz, helps explain why seafaring powers can police the Gulf of Aden in harmony while feuding over the law of the sea in the East China Sea and South China Sea. It’s because the mission is apolitical. Counterpiracy is the overriding priority for the nations that have dispatched vessels to the waters off Somalia. Few if any of them have cross-cutting interests or motives that might disrupt the enterprise. It’s easy to work together when the partners bring little baggage to the venture.

[…]

You see where I’m going with this. The expedition to the Gulf of Aden is an easy case. It proves a trivial result, namely that rivals can collaborate for mutual gain when they have the same interests in an endeavor. Now plant yourself in East Asia and survey the strategic terrain within the perimeter separating the Indian from the Pacific Ocean. China views the South China Sea, to name one contested expanse, not as a commons but as offshore territory. Indeed, Beijing asserts “indisputable sovereignty” there.

Such pretensions grate on Southeast Asian states, while the United States hopes to rally coalitions and partnerships to oversee the commons. But if Beijing is serious about the near seas’ constituting “blue national soil” — and our Chinese friends are nothing if not sincere — then outsiders policing these waters must look like invaders. How else would you regard foreign constables or armies roaming your soil — even for praiseworthy reasons — without so much as a by-your-leave?

September 3, 2012

Military-political jockeying in the East China Sea

At sp!ked, James Woudhuysen has a long essay on the many tiny islands in the East China Sea (and South China Sea) that may feature in future shooting wars:

Outside East Asia, very few people know where the Senkaku islands are. But inside East Asia, the Senkaku prompt great bitterness between Japan, China and Taiwan. At stake is the national pride of each country, which believes that it alone owns them. At stake also are each country’s hopes that it might find oil or gas nearby, and its desire to sail round them unimpeded. But there is more. The Senkaku, and islands like them, signify how, among all the continents in the world, Asia’s past century has been the most enduringly explosive — and how its next could follow the same pattern.

Two hundred nautical miles (nm) west of the Japanese prefecture of Okinawa, 200 nm east of the province of Fujian in the People’s Republic of China, and just 120 nm north-east of Taiwan, there lies an archipelago of five uninhabited islands, covering just seven square kilometres and covered in jungle. Coming from Tokyo, a team of 25 city officials, surveyors and — inevitably — estate agents circled the islands just this weekend, hoping to reinforce Japan’s control over them. In the past, similar moves by both Japan and China have prompted fury, and not a little diplomatic concern elsewhere.

In mid-August, a group of Chinese sailed to the islands in order to uphold Beijing’s claim to them, only to meet with deportation at the hands of Japan. A little later, 150 Japanese nationalists came by in a flotilla and 10 of them swam ashore to raise the Japanese flag. Then, in the latest of a series of tit-for-tat episodes stretching back years, demonstrators in several Chinese cities insisted that Japan get out of the islands. All that’s missing now is that, on top of Tokyo’s rule over what it calls Senkaku and Beijing’s claim over what it calls Diaoyu, is a Taiwanese incursion over what they call the Diaoyutai.

What’s going on? Could all this lead to some kind of fearsome war between Japan, China and Taiwan? And why are there disputes not only in the East China Sea, but also in the South China Sea? There, south-east of Hainan Island (China) and east of Vietnam, China controls the Paracel Islands and resists the complaints of Taiwan and Vietnam about them. There, too, all three parties occupy and are in contention over the myriad Spratly islands, which, lying west of the Philippines and north of Malaysia and Brunei, are also partly controlled and certainly contested by these three nations.

July 23, 2012

China’s latest ploy in the South China Sea

To cement Chinese claims to the vast majority of the South China Sea, a garrison is being established in the Paracel Islands:

China’s powerful Central Military Commission has approved the formal establishment of a military garrison for the disputed South China Sea, state media said, in a move which could further boost tensions in already fractious region.

The Sansha garrison would be responsible for “national defence mobilisation … guarding the city and supporting local emergency rescue and disaster relief” and “carrying out military missions”, the Xinhua news agency said on Sunday.

China has a substantial military presence in the South China Sea and the move is a further assertion of its sovereignty claims after it last month upped the administrative status of the seas to the level of a city, which it calls Sansha.

Sansha city is based on what is known in English as Woody Island, part of the Paracel Islands also claimed by Vietnam and Taiwan.

May 13, 2012

China increases their naval presence near Scarborough Shoal

I posted an item last month about the stand-off between the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the Philippine ship BRP Gregorio del Pilar (a former USCG cutter) in the Scarborough Shoal. Now there’s a report from Hong Kong’s largest English-language newspaper that China is sending another flotilla to the area:

China has sent five warships to the disputed Scarborough Shoal off the west coast of the Philippines with the warning that Beijing is ready for “any escalation” of the conflict.

That comes as the outgunned Philippines looks to the United States for naval support in South China Sea territory that may be rich in energy sources.

The five warships are said to be among the most advanced vessels in the Chinese fleet.

They include ships with state-of-the-art systems against attack from the sky, while one is an assault ship that carries 20 amphibious tanks and specialized fighting teams among 800 personnel.

Japanese surveillance aircraft saw the flotilla west of Okinawa and sailing south on Sunday.

Without American support, the Philippine navy is completely out-classed by the PLAN (aside from a large number of in-shore patrol craft, there are only 14 combat-capable ships). And it’s not clear that the US will want to escalate tension at this moment, especially over something like the Scarborough Shoal.

H/T to David Akin for the link.

April 12, 2012

Chinese vessels left in possession of Scarborough Shoal as Philippine ship withdraws

An update on the BBC News website about the stand-off between Chinese and Philippine ships in the disputed Scarborough Shoal area of the South China Sea:

Earlier on Thursday a Philippine coastguard vessel arrived in the area, known as the Scarborough Shoal.

The Philippines also says China has sent a third ship to the scene.

The Philippine foreign minister said negotiations with China would continue. Both claim the shoal off the Philippines’ north-west coast.

The Philippines said its warship found eight Chinese fishing vessels at the shoal when it was patrolling the area on Sunday.

The BBC article doesn’t name the Philippine ship, but it’s likely to be the BRP Gregorio del Pilar (formerly the USCGC Hamilton):

Photo from Wikipedia

China’s view of its borders in the South China Sea clashes wildly with those of its neighbours and the international community:

In a statement, the Philippines said that its navy boarded the Chinese fishing vessels on Tuesday and found a large amount of illegally-caught fish and coral.

Two Chinese surveillance ships then apparently arrived in the area, placing themselves between the warship and the fishing vessels, preventing the navy from making arrests.

The Philippines summoned Chinese ambassador Ma Keqing on Wednesday to lodge a protest over the incident. However, China maintained it had sovereign rights over the area and asked that the Philippine warship leave the waters.