Extra Credits

Published on 13 Mar 2018H.G. Wells brought his socialist perspective to science fiction, creating great works that really ask us to look at where the human condition will take us hundreds of years from now.

March 14, 2018

March 7, 2018

The History of Sci Fi – Jules Verne – Extra Sci Fi – #1

Extra Credits

Published on Mar 6, 2018Let’s start our journey to the center of hard science fiction: the works of Jules Verne, who imagined the technological wonders humanity could — and would — create in the twentieth century.

March 5, 2018

February 15, 2018

The Martian Chronicles – The New Martians – Extra Sci Fi – #13

Extra Credits

Published on 13 Feb 2018Ray Bradbury’s last Martian story, “The Million Year Picnic,” offers a much more optimistic look at humanity. We have proven ourselves very capable destroyers, but we also have the capacity to improve and learn from our mistakes.

February 13, 2018

Elon Musk as Heinlein’s Delos D. Harriman – “Selling the moon is just what Musk is doing”

I suspect I’d recognize a lot of the books in Colby Cosh‘s collection, as we’re both clearly Robert Heinlein fans. In a column yesterday, he pointed out the strong parallels between Heinlein’s fictional “Man Who Sold the Moon” and his closest counterpart in our timeline, Elon Musk:

Written between 1939 and 1950 for quickie publication in pulp magazines, the Future History is a series of snapshots of what is now an alternate human future — one that features atomic energy, solar system imperialism, and the first steps to deep space, all within a Spenglerian choreography of social progress and occasional resurgent barbarity. It stands with Isaac Asimov’s Foundation trilogy as a monument of golden-age science fiction.

[…]

The result, in the key story of the Future History, is an uncannily accurate description of the design and launch of a Saturn V rocket. (Written before 1950, remember.) But because Heinlein happened not to be interested in electronic computers, all the spacefaring in his books is done with the aid of slide rules or Marchant-style mechanical calculators (which, in non-Heinlein history, had to become obsolete before humans could go to Luna at all). Heinlein sends people to colonize the moon, but nobody there has internet, or is conscious of its absence.

Given that his ideas about computers were from the pre-computer era and even the head of IBM thought there’d be a worldwide demand for a very small number of his company’s devices, that’s not surprising at all. In one of his best novels, a single computer runs almost all of the life support, heat, light, transportation and communication systems on Luna … and is self-aware, but lonely. In later works where computers appear, they tend to be individual personalities or even minor characters, but they’re anything but ubiquitous: powerful, but rare.

I suspect the lack of an internet-equivalent derives both from the nature of his conception of how computing would progress and a form of the Star Trek transporter problem – it solves too many plot issues that could otherwise be usefully woven into stories.

The “key story” I just mentioned is called “The Man Who Sold The Moon.” And if you’re one of the people who has been polarized by the promotional legerdemain of Elon Musk — whether you have been antagonized into loathing him, or lured into his explorer-hero cult — you probably need to make a special point of reading that story.

The shock of recognition will, I promise, flip your lid. The story is, inarguably, Musk’s playbook. Its protagonist, the idealistic business tycoon D.D. Harriman, is what Musk sees when he looks in the mirror.

“The Man Who Sold The Moon” is the story of how Harriman makes the first moon landing happen. Engineers and astronauts are present as peripheral characters, but it is a business romance. Harriman is a sophisticated sort of “Mary Sue” — an older chap whose backstory encompasses the youthful interests of the creators of classic pulp science fiction, but who is given a great fortune, built on terrestrial transport and housing, for the purposes of the story.

February 7, 2018

The Martian Chronicles – Too Human – Extra Sci Fi – #12

Extra Credits

Published on 6 Feb 2018The second half of Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles can be described as “the human cycle” — a reflection on humanity’s seemingly insatiable need to conquer and consume every last bit of our own culture.

February 1, 2018

The Martian Chronicles – A Dying Race – Extra Sci Fi – #11

Extra Credits

Published on 30 Jan 2018We’re diving into Ray Bradbury’s short stories about life on Mars — and how that life reacts when it encounters human life, and what *their* reaction says about American society in the Cold War era.

January 26, 2018

Ursula K. Le Guin, RIP

I’m sorry to say that I’ve never read any of her work, but this obituary by Jude Karabus (especially this section) makes me think I missed out:

A lot of her work – like that of all the literary greats – had to do with thought experiments: What if the relationship between power and gender were different; what if you didn’t – for good or for bad – have to think about whether you wanted to have sex with someone when you interacted with them? What of the profit motive and humankind’s uneasy relationship with war, the environment and its own nature. Her work was, of course, unflinchingly feminist, humanist also.

There is a yellowed, slightly dog-eared copy of 1974’s The Dispossessed, complete with art nouveau-style illustration, on the shelf of the William Morris Gallery in London. It has a placard beneath it that reads something like: “This is the type of thing Morris was banging on about”. (Morris was a 19th-century English textile designer and social activist who brought art to the ‘lower’ classes by mass-producing tiles, wallpaper and other fine furnishings.)

It seems an odd choice by the curator; it’s the only book in the display that wasn’t literally written by a Morris compatriot or a known influence on him, and she was born years after he died. They were certainly of similar political bent, wanted to make art affordable etc, but only if you squint a little. The book was also written before I was born. There’s probably a connection I didn’t understand; perhaps the cover art was “a Morris” (he also painted and wrote poetry) – the terse note propped up against it doesn’t make it clear. But I like to think the curator was grabbed by the throat by her prose, like I was, and was simply looking for any excuse to say: “Here. Sit down. Read this! No really. Read this.”

A quick overview of the life and work of William Morris here.

January 25, 2018

The Canals of Mars – Eye of the Beholder – Extra Sci Fi – #10

Extra Credits

Published on 23 Jan 2018The Canals of Mars ignited so many imaginations, especially in science fiction stories, but they never really existed. What made us believe in them? And why did so many writers keep dreaming about them even after the theory had been disproved?

January 24, 2018

Charles Stross on Heinlein’s “Crazy Years” notion

Heinlein called it, back in the 1940s, and Charles Stross provides a few more data points to prove he was quite right:

Many, many years ago, in the introduction to my first short story collection, I kvetched about how science fictional futures obsolesce, and the futures we expect look quaint and dated by the time the reality rolls round.

Around the time I published “Toast” (the title an ironic reference to the way near-future SF gets burned by reality) I was writing the stories that later became Accelerando. I hadn’t really mastered the full repertoire of fiction techniques at that point (arguably, I still haven’t: I’ll stop learning when I die), but I played to my strengths — and one technique that suited me well back then was to take a fire-hose of ideas and spray them at the reader until they drowned. Nothing gives you a sense of an immersive future like having the entire world dumped on your head simultaneously, after all.

Now we are living in 2018, round the time I envisaged “Lobsters” taking place when I was writing that novelette, and the joke’s on me: reality is outstripping my own ability to keep coming up with insane shit to provide texture to my fiction.

Just in the past 24 hours, the breaking news from Saudi Arabia is that twelve camels have been disqualified from a beauty pageant because their handlers used Botox to make them more handsome. (The street finds its uses for tech, including medicine, but come on, camel beauty pageant botox should not be a viable Google search term in any plausible time line.) Meanwhile, home in Edinburgh, eight vehicles have been discovered trapped in an abandoned robot car park during demolition work. This is pure J. G. Ballard/William Gibson mashup territory, and it’s about half a kilometre from my front door. The world’s top 1% earned 82% of all wealth generated in 2017 — I’m fairly sure this wasn’t what Adam Smith had in mind — and South Korea has such a high suicide rate that the government intends to make organising a suicide pact a criminal offence.

Go home, 2018, you’re drunk. (Or, as Robert Heinlein might have put it: these are the crazy years, and they’re not over yet.)

January 11, 2018

William Gibson: The Gernsback Continuum – Semiotic Ghosts – #8

Extra Credits

Published on Jan 9, 2018Ways that we dream about the world sometimes create a shared vision that we start to believe is real. When William Gibson first explored these “semiotic ghosts” of a pristine American future in the Gernsback Continuum, he showed how these visions of modern technology can separate us from our own reality and the personal meaning our world should hold for us.

January 4, 2018

“This is what you get when you touch the Orb”

Jonah Goldberg thinks he’s identified the moment our timeline went screwy, sorta:

Ever since Donald Trump touched the Orb, praise be upon it, I’ve been making “This is what you get when you touch the Orb” jokes.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, I’ll tell you: On his trip to the Middle East in May, President Trump, along with the Saudi king and the president of Egypt, laid his hands on a glowing white orb for two minutes (which strikes me as a long time to touch an orb).

The image was like a mix of J.R.R. Tolkien and 1970s low-budget Canadian sci-fi. It looked like they were calling forth powerful eldritch energies from the chthonic depths or perhaps the forbidden zone.

Ever since then, when things have gotten weird, I’ve credited the Orb. For instance, when the Guardian reported that sex between Japanese snow monkeys and Sika deer may now constitute a new “behavioral tradition,” I tweeted, “the Orb has game, you can’t deny it.” When Roy Moore, the GOP Alabama Senate candidate, was plausibly accused of preying on teenagers and many evangelical leaders rallied to his defense, invoking biblical justifications for groping young girls, I admired the Orb’s cunning. And when the bunkered Moore decided to give one of his only interviews to a 12-year-old girl, I sat back and marveled at the Orb’s dark sense of humor.

But I know in my heart that it’s not the Orb’s fault things have gotten so weird, for the simple reason that rampant weirdness predates the Orb-touching by years.

I have a partial theory as to why, and it doesn’t begin with Trump. It begins with a failure of elites and the institutions they run.

December 21, 2017

William Gibson: The 80s Revolution – Extra Sci Fi – #7

Extra Credits

Published on 19 Dec 2017Start your free 1-month trial for The Great Courses Plus! http://ow.ly/3iLM30egcfR

After Star Wars, the science fiction genre suddenly became a pop culture darling, and a flood of schlocky imitations followed. William Gibson led the charge to reclaim space in the genre for his concept of future history – one that, in turn, eventually launched cyberpunk.

UFOs? Again?

I must admit I share Colby Cosh’s just disproven belief that we were done with the UFO craze:

There can no longer be any doubt: every fashion phenomenon does come back. I, for one, really thought we had seen the last of UFO-mania. When I was a boy, the idea of stealthy extraterrestrial visitors zooming around in miraculous aircraft was everywhere in the nerdier corners of popular culture. If you liked comic books or paperback science fiction or Omni magazine — and especially if those things were among the staples of your imaginative diet — there was no getting away from it.

Anyone remember the NBC series Project U.F.O. (1978-79), inspired by the USAF’s real Project Blue Book program? As the anthology show’s Wikipedia page observes, most episodes had the plot of a Scooby-Doo cartoon, only backwards: they would end with the investigating protagonists discovering that UFOs remained impenetrably Unidentifiable, but must be “real” craft capable of physically improbable manoeuvres. (I know citing Wikipedia will savour of pumpkin-spice holiday laziness on my part, but the Scooby thing is a truly perceptive point by some anonymous Wiki-genius.)

Then, at the end of the show, a disclaimer would appear on-screen: “The U.S. Air Force stopped investigating UFOs in 1969. After 22 years, they found no evidence of extra-terrestrial landings and no threat to national security.”

[…]

There are very good reasons for a superpower’s military apparatus to devote a little money to following up UFO sightings. “Threat Identification”? Sure, whatever. Plenty of U.S. military flyers have seen UFOs, and these people ought to be comfortable reporting odd occurrences without ridicule. But if I were American, I would definitely want most of that budget to go to Scully rather than Mulder. Don’t throw cash at someone who really, really wants to believe.

What I find vexing is that most of the response to the Times story has been in the spirit of “Whoa, aliens!” rather than “Taxpayers got robbed.” Young people may know on some level that ubiquitous good-quality cameras have all but eliminated civilian UFO sightings. But they lack the personal memory of a live, thriving UFO fad, one that bred quasi-scholarly international UFO-study associations along with a whole publishing industry devoted to UFO tales. I wonder if the Times’ piece on UFO research, by the very virtue of its flat-voiced Grey Lady objectivity, is having the same weird effect as that disclaimer they showed at the end of Project U.F.O.

December 14, 2017

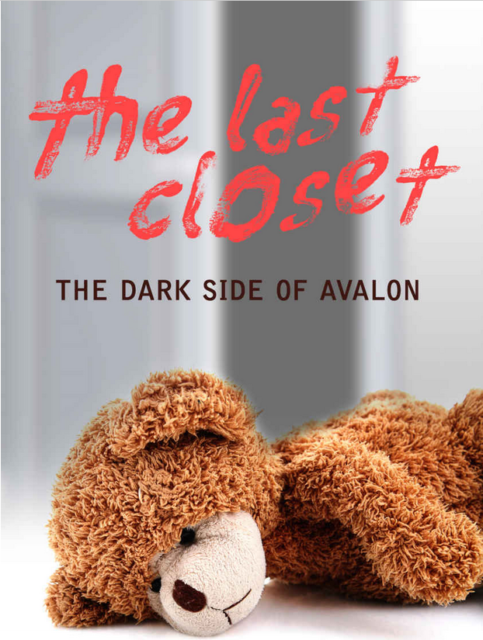

The Last Closet: the Dark Side of Avalon

Just saw this on Facebook:

Marion Zimmer Bradley was a bestselling science fiction author, a feminist icon, and was awarded the World Fantasy Award for lifetime achievement. She was best known for the Arthurian fiction novel The Mists of Avalon and for her very popular Darkover series.

She was also a monster.

The Last Closet: The Dark Side of Avalon is a brutal tale of a harrowing childhood. It is the true story of predatory adults preying on the innocence of children without shame, guilt, or remorse. It is an eyewitness account of how high-minded utopian intellectuals, unchecked by law, tradition, religion, or morality, can create a literal Hell on Earth.

The Last Closet is also an inspiring story of survival. It is a powerful testimony to courage, to hope, and to faith. It is the story of Moira Greyland, the only daughter of Marion Zimmer Bradley and convicted child molester Walter Breen, told in her own words.

While I was never a fan of MZB, I was still shocked to hear about her private life. I haven’t read the book, but I have no reason to believe it’s not completely true.