Mancur Olson, in his book The Logic Of Collective Action, highlighted the central problem of politics in a democracy. The benefits of political market-rigging can be concentrated to benefit particular special interest groups, while the costs (in higher taxes, slower economic growth, and many other second-order effects) are diffused through the entire population.

The result is a scramble in which individual interest groups perpetually seek to corner more and more rent from the system, while the incremental costs of this behavior rise slowly enough that it is difficult to sustain broad political opposition to the overall system of political privilege and rent-seeking.

When you add to Olson’s model the fact that the professional political class is itself a special interest group which collects concentrated benefits from encouraging rent-seeking behavior in others, it becomes clear why, as Olson pointed out, “good government” is a public good subject to exactly the same underproduction problems as other public goods. Furthermore, as democracies evolve, government activity that might produce “good government” tends to be crowded out by coalitions of rent-seekers and their tribunes.

This general model has consequences. Here are some of them:

There is no form of market failure, however egregious, which is not eventually made worse by the political interventions intended to fix it.

Political demand for income transfers, entitlements and subsidies always rises faster than the economy can generate increased wealth to supply them from.

Although some taxes genuinely begin by being levied for the benefit of the taxed, all taxes end up being levied for the benefit of the political class.

The equilibrium state of a regulatory agency is to have been captured by the entities it is supposed to regulate.

The probability that the actual effects of a political agency or program will bear any relationship to the intentions under which it was designed falls exponentially with the amount of time since it was founded.

The only important class distinction in any advanced democracy is between those who are net producers of tax revenues and those who are net consumers of them.

Corruption is not the exceptional condition of politics, it is the normal one.

Eric S. Raymond, “Some Iron Laws of Political Economics”, Armed and Dangerous, 2009-05-27.

April 5, 2018

QotD: ESR’s “Iron Laws of Political Economics”

March 29, 2018

March 24, 2018

March 22, 2018

Unaccountable federal agency refuses to answer to the senator who wanted it to be unaccountable in the first place

Perhaps this is a teaching moment for Senator Elizabeth Warren, says A. Barton Hinkle:

If Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren had taken a page out of Virginia Delegate Nick Freitas’ book, she might not be in the pickle she is today.

Warren is spitting mad at Mick Mulvaney, the Office of Management and Budget director who does double duty heading up an agency whose creation Warren championed: the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). The CFPB’s previous director was an ideological ally of Warren. Since Mulvaney took over, Warren has ripped the agency’s decisions. Warren said Mulvaney is giving “the middle finger” to consumers, and she railed at Mulvaney’s indifferent response to the 10 (!) letters she has sent him demanding answers to more than 100 questions.

The other day she tweeted that she is giving Mulvaney “one last chance.” Yet as The Wall Street Journal points out, she has only herself to blame for her apparent impotence.

Time and again during debate over the CFPB, conservatives and libertarians warned that its powers were too great and that its accountability to the other branches of government was too limited. But that was just the way Warren and other supporters wanted things. Neither Congress nor other political forces could influence an unaccountable regulatory agency. Now Warren finds herself thwarted by the very lack of oversight she championed.

Be careful what you wish for.

[…]

Philosopher John Rawls famously invented a mechanism for doing just that: the “veil of ignorance”: If you are designing the rules for a society, you should assume that you know nothing about your place in that society. If your race, age, physical abilities, mental prowess, and so forth are all a complete mystery, then you are likely to design a political-economic system that is fair to all. Just in case you wind up at the bottom of the social pile.

Having a president who makes policy through signing statements, his “pen and phone,” and other forms of executive action, for example, seems brilliant when the opposing party controls Congress. It seems less so when the opposing party controls the White House.

Should intelligence agencies keep tabs on Islamists who might pose a threat of domestic terrorism? Then don’t be surprised if a different administration turns the focus to right-wing militias.

February 26, 2018

QotD: Regulations in the EU

As for the idea that the individual should be as free as possible from state coercion, this is regarded as the ultimate Anglophone fetish. Whenever the EU extends its jurisdiction into a new field — decreeing what vitamins we can buy, how much capital banks must hold, how herbal remedies are to be regulated — I ask what specific problem the new rules are needed to solve. The response is always the same: “But the old system was unregulated!” The idea that absence of regulation might be a natural state of affairs is seen as preposterous. In Continental usage “unregulated” and “illegal” are much closer concepts than in places where lawmaking happens in English.

Daniel Hannan, Inventing Freedom: How the English-speaking peoples made the modern world, 2013.

February 22, 2018

QotD: The importance of defining your terms

If you don’t understand these [gun-related] terms already, why should you care? You should care because when you misuse them, you signal substantially broader gun restrictions than you may actually be advocating. So, for instance, if you have no idea what semi-automatic means, but you’ve heard it and it sounds scary, and you assume that it means some kind of machine gun, so you argue semi-automatics should be restricted, you’ve just conveyed that most modern handguns (save for revolvers) should be restricted, even if that’s not what you meant.

It’s hard to grasp the reaction of someone who understands gun terminology to someone who doesn’t. So imagine we’re going through one of our periodic moral panics over dogs and I’m trying to persuade you that there should be restrictions on, say, Rottweilers.

Me: I don’t want to take away dog owners’ rights. But we need to do something about Rottweilers.

You: So what do you propose?

Me: I just think that there should be some sort of training or restrictions on owning an attack dog.

You: Wait. What’s an “attack dog?”

Me: You know what I mean. Like military dogs.

You: Huh? Rottweilers aren’t military dogs. In fact “military dogs” isn’t a thing. You mean like German Shepherds?

Me: Don’t be ridiculous. Nobody’s trying to take away your German Shepherds. But civilians shouldn’t own fighting dogs.

You: I have no idea what dogs you’re talking about now.

Me: You’re being both picky and obtuse. You know I mean hounds.

You: What the fuck.

Me: OK, maybe not actually ::air quotes:: hounds ::air quotes::. Maybe I have the terminology wrong. I’m not obsessed with vicious dogs like you. But we can identify kinds of dogs that civilians just don’t need to own.

You: Can we?Because I’m just talking out of my ass, the impression I convey is that I want to ban some arbitrary, uninformed category of dogs that I can’t articulate. Are you comfortable that my rule is going to be drawn in a principled, informed, narrow way?

So. If you’d like to persuade people to accept some sort of restrictions on guns, consider educating yourself so you understand the terminology that you’re using. And if you’re reacting to someone suggesting gun restrictions, and they seem to suggest something nonsensical, consider a polite question of clarification about terminology.

Ken White, “Talking Productively About Guns”, Popehat, 2015-12-07.

February 21, 2018

QotD: Regulation

… “regulation” could also be described as high-handed and ignorant interference in the mutually advantageous deals contracted voluntarily among the miserable serfs of the state, interference at best inspired by antique theories of natural monopoly and using antique policies appropriate to obsolete technologies, and at worst by conspiracies to benefit existing rich people, backed by state violence. Much of regulation, looked at coldly, would fall under such a definition, if not immediately on its passage, then after a few years of technological change or regulatory capture.

Deirdre N. McCloskey, Bourgeois Equality, 2016.

February 18, 2018

The legal loophole that allows profiteering scumbags like Martin Shkreli to gouge the public

The US pharmaceutical market is a long way from a freely competitive environment, largely due to the amount of regulatory oversight required by lawmakers and enforced by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Among all the regulatory checks and balances, there’s one weird trick that allows predatory companies to reap excess profits legally — the “restricted distribution” loophole:

For immunocompromised adult patients who have the toxoplasmosis parasite, the FDA recommends taking 50 to 75 milligrams of Daraprim a day for up to three weeks, followed by half that dosage for an additional four to five weeks. So at the high end, an adult course of Daraprim therapy for a U.S. patient used to cost around $1,350 total.

While that might not seem cheap, it was a drop in the bucket compared to the cost after Turing Pharmaceuticals, Shkreli’s company, bought the rights to Daraprim and jacked the price up to $750 per pill in 2015. That move increased the cost of one course of treatment to around $75,000.

At that point you might have expected another company to jump in and start offering a generic version of the drug. But Shkreli used a regulatory loophole to keep that from happening.

You see, when a generic manufacturer wants to create a cheap version of a branded drug, it has to buy thousands of doses from the manufacturer in order to run comparison tests. Generic manufacturers use the results of these tests to prove to the FDA that their version is identical to the branded drug that the agency has already approved.

More often than not, the company that holds the marketing and distribution rights to a branded drug will sell those comparison doses to the generic manufacturer without being obstructionist, because that’s the trade-off for receiving a 20-year monopoly by way of a drug patent: The branded manufacturer gets to charge whatever they want for years and years without facing competition, and in exchange for that government-backed monopoly, it’s supposed to sell equivalency samples to generic companies.

But what if the company is run by an unscrupulous asshole like Martin Shkreli? Then it might opt to put the drug into what’s called “restricted distribution,” which means no distributor anywhere can sell comparison samples to a generic manufacturer.

The FDA originally created the concept of restricted distribution to limit the availability of drugs that might be dangerous. Methadone, for instance, was first approved in the 1940s as a painkiller. In the 1970s, the FDA restricted its availability because regulators didn’t want the opioid used for anything other than the treatment of opioid dependence. Even today, methadone can be dispensed only in highly regulated settings and only for one approved reason.

In 2007, Congress empowered the FDA to create an entire system of safety controls beyond restricted distribution, and the agency now requires the manufacturers of certain substances to develop Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) to prevent misuse and abuse of potentially problematic compounds.

The list of approved drugs that the FDA says must have an REMS is here. Daraprim is not on that list. You can’t get high off it. It’s not habit forming. Yes, the FDA label says it can be carcinogenic after long periods of use, and that it might cause birth defects if used in high doses by pregnant women. These potential effects are serious, but there is no post-market data suggesting that Daraprim is causing more harm than benefit in the intended patient population. Shkreli’s company put Daraprim into restricted distribution to boost their profits, not protect patients.

February 14, 2018

QotD: Portuguese quality of life … or “Is Portugal a shithole?”

You see, you can judge a country’s status as an … ah… excrement sinkhole by figuring out “Migration out or in?”

In Portugal this picture is complicated. They are suffering “brain drain” as their youngest, brightest and most educated decamp for Germany, England, or even Brazil (where the picture is also complicated) but at the same time they receive immigrants from Africa, Brazil, South America, China and, weirdly, Russia (I’ve never figured out if these are descendants from people who took their crappy cars when the wall came down, and drove until they hit the ocean (or drove/walked till they hit the ocean) or whether they’re a fresh migration. I know the first existed, but I haven’t sussed out the other particulars.)

So, Portugal is not a shithole. What it is is a country so tied down by regulations, rules, and the ever present weight of tradition (Portugal, like many Baltic countries produces way more history than it can consume locally) that it works at cross purposes to itself.

Looking at what Portuguese (at least some) can do abroad, in terms of insane amounts of work and sometimes success, one assumes that if Portugal could eschew its perennial fascination with socialism, it would … well… I don’t know, but it would be scary for good or ill.

I mean for a country tied up with socialism (first national, then international) for the best part of a century, it’s not doing badly at all. Look at it this way: it hasn’t gone Venezuela. And the gentleman in the back who just said that’s because they can’t do anything efficiently, not even socialism, is just being mean. Yes, the Portuguese have been locked in a tragic fight throughout history with their traditional enemies, the Portuguese, but that’s no reason to look down on them.

Sarah Hoyt, “On Shaking The Dust From One’s Sandals”, According to Hoyt, 2018-01-17.

February 8, 2018

QotD: Minimum prices for wine, a thought experiment

Consider this hypothetical (which, given the poor quality of today’s punditry and publicly discussed economics, is not as far-fetched as it might at first seem): Ostensibly to help raise the incomes of hard-working vintners of low-quality wines – vintners many of whom have children to feed and sick parents to care for, and many of whom also are stuck in their jobs as owners of low-quality vineyards – Congress passes minimum-wine-price legislation: no wine may sell for any price less than $1.00 per fluid ounce. Roughly, that means that the minimum price of a standard-sized – 750ml – bottle of wine becomes $25.00. Armed officers of the state will use deadly force against anyone and everyone who insists on disobeying this diktat.

If proponents of the minimum wage are correct in their economics, then the only effect of this minimum-wine-price diktat will be distributional. Consumers – including retailers and restaurants buying from wholesalers – will continue to buy as much wine, and the same qualities of wine, that they bought before the diktat took effect. The only difference is that, with the diktat in place, owners of low-quality vineyards earn higher incomes, all of which are paid for by consumers who dip further into their own incomes and wealth to fund this transfer. Easy-peasy! Problem solved!

But who in their right mind would suppose that a minimum-wine-price diktat would play out in the manner described above? Who would not see that a wine buyer, obliged to pay at least $25 for a standard-size bottle of wine, will buy only higher-quality wines – wines that before the diktat took effect were fetching at least $25 per bottle (or some price close to that)? Many wine buyers who before the diktat were confronted with the choice of paying either $8.99 for a bottle of indifferent but drinkable chardonnay and $25.00 for a bottle of much more elegant and enjoyable chardonnay opted for the less-pricey bottles. They did so not because they prefer to drink chardonnay that is indifferent to chardonnay that is elegant – they in fact do not have this preference. Rather, they did so because the greater elegance of the pricier chardonnay was not to them worth its higher price. So the low-quality chardonnay found many willing buyers.

Don Boudreaux, “Quotation of the Day…”, Café Hayek, 2016-06-02.

February 3, 2018

Arizona’s legally protected blow-drying cartel

Eric Boehm reports on the fantastic lengths protected businesses will go to to protect themselves from “unlicensed” competitors, even in such areas as hair drying:

Brandy Wells never anticipated the amount of vitriolic abuse she would receive over — of all things — her public support of a proposal to let people blow-dry hair without a state-issued license.

“I’ve been called a cunt, a bitch, an ass, trashy, a puppet, a pawn, repugnant,” Wells says. “And my favorite: ‘your logic on deregulation of cosmetology is much like your hair, dull and flat.'”

Wells says she’s received several attacks from cosmetologists on social media accusing her of being “uneducated” or “clueless” about cosmetology because she doesn’t work in the industry. It’s true that Wells isn’t a licensed cosmetologist (though she does, in fact, know how to use a blow-dryer, she confirmed to Reason), but that’s actually the precise reason why she’s speaking up.

Wells serves as the lone “public member” of the Arizona State Board of Cosmetology. That means she is the only member of the seven-person board who does not work in some capacity as a cosmetologist or with a connection to a cosmetology school. Last month, she voiced her support for House Bill 2011, which would removing blow-drying from the state’s cosmetology licensing requirements. Under current law, using a blow-dryer on someone else’s hair, for money, requires more than 1,000 hours of training and an expensive state-issued license. Blow-drying hair without a license could — incredibly — land you in jail for up to six months.

In response, Wells says, members of the cosmetology profession have sent messages to her employer, the Arizona Chamber of Commerce, suggesting that she should be fired — fired because she thinks people can safely blow-dry hair without 1,000 hours of training!

The cosmetology board is “a group of special interest bullies,” said Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican, in his recent State of the State address. The board, Ducey said, “is going after people who simply want to make a living blow-drying hair. No scissors involved.”

This week, the fight over the so-called “blow-dry bill” spilled into the state legislature. The state House Military, Veterans, and Regulatory Affairs Committee held its first hearing on the bill, and licensed cosmetologists packed the room to speak one-by-one about the potential dangers of letting unlicensed professionals blow-dry hair

February 2, 2018

QotD: Infrastructural sclerosis

I have an op-ed in the Boston Globe today on infrastructure, addressing the issue of quality rather than quantity of investment. Rachel Lipson, a graduate student at Harvard, and I describe the fiasco that has emerged from what should have been a routine maintenance project on the Anderson Memorial Bridge over the Charles River next to my office in Cambridge. Though the bridge took only 11 months to build in 1912, it will take close to five years to repair today at a huge cost in dollars and mass delays.

Investigating the reasons behind the bridge blunders have helped to illuminate an aspect of American sclerosis — a gaggle of regulators and veto players, each with the power to block or to delay, and each with their own parochial concerns. All the actors — the historical commission, the contractor, the environmental agencies, the advocacy groups, the state transportation department — are reasonable in their own terms, but the final result is wildly unreasonable.

At one level this explains why, despite the overwhelming case for infrastructure investment, there is so much resistance from those who think it will be carried out ineptly. The right response is to advocate for reforms in procurement policies, regulatory policies and government procedures to make the investment process more efficient and effective. This is all clear enough.

At another level, though, our story may illustrate phenomena that go way beyond infrastructure. I’m a progressive, but it seems plausible to wonder if government can build a nation abroad, fight social decay, run schools, mandate the design of cars, run health insurance exchanges, or set proper sexual harassment policies on college campuses, if it can’t even fix a 232-foot bridge competently. Waiting in traffic over the Anderson Bridge, I’ve empathized with the two-thirds of Americans who distrust government.

Larry Summers, “Why Americans don’t trust government”, Washington Post, 2016-05-26.

January 28, 2018

The origins of the minimum wage

In Ontario, many businesses are still struggling to cope with the provincial government’s mandated rise in the minimum wage (the Tim Horton’s franchisees being the current Emmanuel Goldsteins as far as organized labour is concerned). In this essay for the Foundation for Economic Education, Pierre-Guy Veer points out that most franchise businesses have very low profit margins (2.4% for McDonalds franchises, for example) meaning that they can’t just pay the higher wages without a problem, and that the original intent of minimum wage legislation in the US was actually to drive down employment for certain ethnic and racial groups:

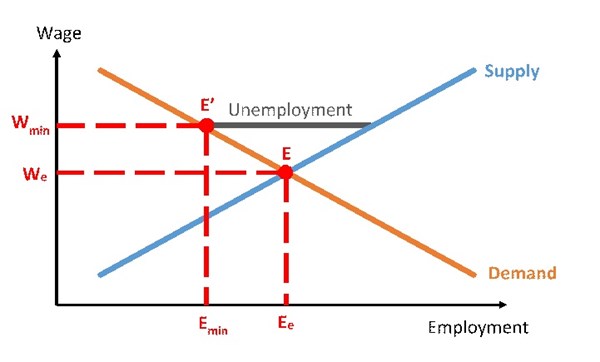

Normally, wages are determined at the intersection of supply (employees offering their services, the blue line) and demand (employers wanting workers, the orange line), the letter E. Since working in retail or restaurants requires little more than a high school diploma, that equilibrium is much lower than, say, a heart surgeon, who must endure years of training and study.

But when governments come and impose a minimum wage (the dark line), wages do increase… at the expense of workers. With a base wage now at E’, more workers want to work but fewer employers want to hire because of the increased cost. The newly formed triangle is made of surplus workers, i.e. unemployed workers who can’t find a job. This unlucky Brian meme summarizes the situation of what minimum wage is: wage eugenics.

And don’t think it’s a vice; creating unemployment was the explicit goal of imposing a minimum wage. It was a Machiavellian scheme imagined during the so-called Progressive Era (late 19th Century to about the 1920s), where it was thought that governments could better humanity by “weeding out” undesirables – in other words, eugenics.

In the U.S., this eugenic attitude was explicitly aimed at African Americans, whose (generally) lower productivity gave them lower wages. To “fight” this problem nationwide, the Hoover administration passed, in 1931, the Davis-Bacon Act in order to impose “prevailing wage” (usually unionized) on all federal contracts. It was a thinly veiled attempt to “weed out” non-unionized workers, who were either African American or immigrant, in order to protect unionized, white jobs. Supporters of the bill, like Representative Clayton Algood, were very explicit in their racist intents:

That contractor has cheap colored labor that he transports, and he puts them in cabins, and it is labor of that sort that is in competition with white labor throughout the country.

But while the racist intent of the minimum wage has disappeared, its effect is always very real. It greatly affects the people it wants to help, i.e. low-skilled workers, and leaves them with fewer options. So don’t be fooled by unemployment statistics from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Youth participation rates (ages 16-19) are still hovering around all-time lows (affected, among others, by minimum wage laws); this means that fewer of them are looking for jobs, decreasing unemployment figures.

It gets worse when breaking down races; only 28.8 percent of African American youth were working or looking for a job, compared to 31.6 for Hispanics and 36.7 percent for whites in December 2017.

January 27, 2018

Burger King swings and misses in their first attempt at entering political discussions

Tho Bishop explains why the second-rate burger business fails to convince:

For one, Burger King does not have a “Whopper neutrality” policy – and for good reason. If a family of five places a large order, while the next customer simply orders an ice cream cone, most Burger King employees will not refuse to serve up the dessert until after they fulfill the first order. The aim is to serve as many customers, as quickly as possible.

Similarly, a Whopper meal comes in various sizes – all with different prices – all so that customers have more flexibility based on having their food desires met. Imagine if a government regulator decided that since Americans have a right to have their thirst quenched – no matter its size – all fast food restaurants had to price all drink sizes the same? The result would be the prices for small drinks going up, while restaurants having to submit to occasional inspections by government agents to make sure no one was violating beverage neutrality laws. (This of course would still manage to not be the worst soda-related policy that’s been proposed.)

Additionally, Burger King certainly has the right to not prioritize delivering their customers food in a timely matter, just as customers have a right to avoid their services as a result. Whether or not the customers in the video were authentic or not, their reaction to the absurd fictional policy is how you’d expect someone to act. The video suggests that none of them would be excited about returning to Burger King if this had become actual franchise operating procedure. Once again, the market has its own ways of punishing bad actors.

Which is precisely why I will be avoiding Whoppers myself for the foreseeable future.

At Reason, Nick Gillespie comments on the video:

The joke in the video is that customers must pay $26 to get a Whopper “hyperfast.” If they go with the standard price, it takes forever. Because you know, Net Neutrality rules that were formalized in 2015 somehow magically altered the way internet service providers (ISPs) delivered data to their customers. Before 2015, the internet was a morass of shakedown artists who forced all of us to pay extra for this or that site. And now that Net Neutrality has been repealed, the ‘net has reverted to a Hobbesian world in which access is nasty, brutish, and metered.

Oh wait, in fact, the average speed and number of internet connections kept growing regardless of the regulatory regime. The FCC’s most recent Internet Access Services Report counted 104 million fixed internet connections, a new high. That number doesn’t count mobile or satellite connections. Eighty percent of census tracts had at three or more ISPs offering connections of 10 Mbps downstream and 1 Mbps upstream and another 17 percent had two ISPs doing the same (figure 4). So 97 percent of America can go elsewhere when it comes to basic internet connections that allow the sort of streaming, surfing, and gaming we want. Just as customers do with Burger King, we can say, “Screw it, I’m going to McDonald’s.” In 2016, 56 million residential connections offered at least 25 Mbps upstream speeds. That’s up from about 22 million in 2013 (figure 8). How did that progress happen before the 2015 open internet order?

Watching the responses by customers helps explain why Net Neutrality rules as mandated by the FCC under Tom Wheeler were unnecessary. After all, for all the hysteria kicked up around the need for such rules, proponents went begging for examples of ISPs throttlng traffic or blocking sites in systematic ways. ISPs don’t actually enjoy pure-monopoly conditions, but even if they did, customers would raise holy hell if they were treated as poorly as Burger King acts in this video.

January 24, 2018

QotD: What is a human life worth?

Government itself has this problem too in fact and the method generally used to deal with it is price mechanism. We generally try to work out what is the statistical value of a life by looking around at what people do and how much they charge for the risk. Some people work in more dangerous jobs (trawlerman, lumberjack), so what’s the difference in wages between a more dangerous and less dangerous job (trying, of course, to keep other things like effort, training and so on constant)? People smoke and are willing to pay some sum for a safer car but not an unlimited amount. This process is more of an art than a science, but the U.S. government comes up with numbers in the $4 million to $10 million range for the value of a statistical life.

This is not what a life should be worth. This is what, from observation of what people do, modern Americans think a life actually is worth. Now we can use it to decide on our safety regulations. And it doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about corporations eyeing their profits or government aiding the EPA in setting rules about what corporations may do. We still end up with the same economic point.

If the statistical value of a life is $10 million then a rule, a regulation, a new way of doing something, which costs more than $10 million per life saved is a waste of resources. It’s not just something we might have to think about doing: it’s something that we positively should not do. Equally, something that costs less than $10 million per life saved is something we should do. Either way, we are trying to make sure that we expend our limited and scarce resources in order to produce the greatest human value we can. Spending $20 million on saving one life is a waste of those resources: not spending $500,000 on saving one is a waste of that life which we value more.

Tim Worstall, “Sorry, Salon: The Koch Brothers Are Actually Right”, Forbes, 2016-05-17.