But what about the error correction function of peer review? Surely it’s important to ensure that the literature doesn’t fill up with bullshit? Shouldn’t we want our journals to publish only the most reliable, correct information – data analysis you can set your clock by, conclusions as solid as the Earth under your feet, uncertainties quantified to within the nearest fraction of a covariant Markov Chain Monte Carlo-delineated sigma contour?

Well, about that.

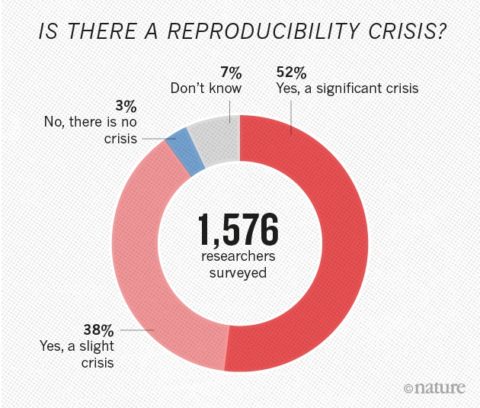

The replication crisis has been festering throughout the academic community for the better part of a decade, now. It turns out that a huge part of the scientific literature simply can’t be reproduced. In many cases the works in question are high-impact papers, the sort of work that careers are based on, that lead to million-dollar grants being handed out to laboratories across the world. Indeed, it seems that the most-cited works are also the least likely to be reproduced (there’s a running joke that if something was published in Nature or Science, you know it’s probably wrong). Awkward.

The scientific community has completely failed to draw the obvious conclusion from the replication crisis, which is that peer review doesn’t work at all. Indeed, it may well play a causal role in the replication crisis.

The replication crisis, I should emphasize, is probably not mostly due to deliberate fraud, although there’s certainly some of that. There was a recent scandal involving the connection of amyloid plaques to Alzheimer’s disease which seems to have been entirely fraudulent, and which led to many millions – perhaps billions – of dollars in biomedical research programs being pissed away, to say nothing of the uncountable number of wasted man-hours. There have been many other such scandals, in almost every field you can name, and God alone knows how many are still buried like undiscovered time bombs in the foundations of various sub-fields. Most scientists, however, are not deliberately, consciously deceptive. They try to be honest. But the different models, assumptions, and methods they adopt can lead to wildly divergent results, even when analyzing the same data and testing the same hypothesis. Beyond that, they can also be sloppy. And the sloppiness, compounded across interlinked citation chains in the knowledge network, builds up.

Scientists know quite well that just because something has received the imprimatur of publication in a peer-reviewed journal with a high impact factor doesn’t mean that it’s correct. But while they know this intellectually, it’s very difficult to avoid the operating assumption that if something has passed peer review it’s probably mostly okay, and they’re not inclined to spend valuable time checking everything themselves. After all, they need to publish their own papers – in order to finish their PhD, get that faculty position, or get that next grant – and papers that are just trying to reproduce the results of other papers, that aren’t doing something novel, aren’t very interesting on their own, hence unlikely to be published. So instead of checking carefully yourself, you assume a work is probably reliable, and you use it as an element of your own work, maybe in a small way – taking a number from a table to populate an empty field in your dataset – or maybe in an important way, as a key supporting measurement or fundamental theoretical interpretative framework.

But some of those papers, despite having been peer reviewed, will be wrong, in small ways and large, and those erroneous results will propagate through your own results, possibly leading to your own paper being irretrievably flawed. But then your paper passes peer review, and gets used as the basis for subsequent work. Over time the entire scientific literature comes to resemble a house of cards.

Peer review gives scientists – and the lay public – a false sense of security regarding the soundness of scientific results. It also imposes an additional, and quite unnecessary, barrier to publication. It frequently takes months for a paper to work its way through the review process. A year or more is not unheard of, particularly if a paper is rejected, and the authors must start the whole process anew at a different journal, submitting their work as a grindstone for whatever rusty old axe the new referee is looking to sharpen. Far from ensuring errors are corrected, peer review slows down the error correction process. A bad paper can persist in the literature – being cited by other scientists – for some time, for years, before the refutation finally makes it to print … at which point some (not all) will consider the original paper debunked, and stop citing it (others, not being aware of the debunking, will continue to cite it). But what if the refutation is itself tendentious? The original authors may wish to reply, but their refutation of the refutation must now go through the peer review process as well, and on and on it interminably drags …

As to what is happening behind the scenes, no one – not the public, not other scientists – has any idea. The correspondence between referees and authors is rarely published along with the paper. Whether the review was meticulous or sloppy, whether the referee’s critiques warranted or absurd, is entirely opaque.

In essence, the peer review process slows down the publication duty cycle, thereby slowing down scientific debate, while taking much of that debate behind closed doors, where its quality cannot be evaluated by anyone but the participants.

John Carter, “DIEing Academic Research Budgets”, Postcards from Barsoom, 2025-03-17.

June 19, 2025

QotD: Peer review and the replication crisis

November 2, 2024

QotD: UBI discourages low-income workers

Not only does it have a high cost, UBI drains the labour force by discouraging work and boosting leisure time, says one big-picture study

Earlier this month, a cross-border team of North American economists published the results of a landmark study, probably the best and most careful yet done, of how low-income workers respond to an unconditional guaranteed income. Not so long ago this would have been a plus-sized news item in narcissistic Canada, for the lead author of the study is a rising economics star at the University of Toronto, Eva Vivalt. The economists, working through non-profit groups, recruited 3,000 people below a certain income cutoff in the suburbs of Dallas and Chicago. A thousand of these, chosen at random, were given a thousand dollars a month for three years. The rest were assigned to a control group that got just $50 a month, plus small extra amounts to encourage them to stay with the study and fill in questionnaires.

That randomization is an important source of credibility, and the study has several other impressive methodological bona fides. If you have an envelope to scribble on the back of, you can see that the payments alone were beyond the wildest dreams of most social science: most of the money was provided by the AI billionaire Sam Altman. But the study also had help from state governments, who agreed to forgo welfare clawbacks from the participants to make sure the observed effects weren’t obscured by local circumstances. Participant households were also screened carefully to make sure nobody in them was already receiving disability insurance. (Free money doesn’t discourage work among people who can’t work — or who absolutely won’t.) And the study combined questionnaire data with both smartphone tracking and state administrative records, yielding an unusually strong ability to answer difficult behavioural questions.

The big picture shows that the free cash — a “universal basic income” (UBI) for a small group of individuals — discouraged paying work, even though everybody in the study was starting out poor. Labour market participation among the recipients fell by two percentage points, even though the study period was limited to three years, and the earned incomes of those getting the cheques declined by $1,500 a year on average. There is no indication that the cash recipients used their augmented bargaining power to find better jobs, and no indication of “significant effects on investments in human capital”, i.e., training and education. The largest change in time use in the experiment group was — wait for it! — “time spent on leisure”.

Colby Cosh, “Universal basic income is a recipe for fiscal suicide (for so many reasons)”, National Post, 2024-07-30.

May 26, 2024

“Naked ‘gobbledygook sandwiches’ got past peer review, and the expert reviewers didn’t so much as blink”

Jo Nova on the state of play in the (scientifically disastrous) replication crisis and the ethics-free “churnals” that publish junk science:

Proving that unpaid anonymous review is worth every cent, the 217 year old Wiley science publisher “peer reviewed” 11,300 papers that were fake, and didn’t even notice. It’s not just a scam, it’s an industry. Naked “gobbledygook sandwiches” got past peer review, and the expert reviewers didn’t so much as blink.

Big Government and Big Money has captured science and strangled it. The more money they pour in, the worse it gets. John Wiley and Sons is a US $2 billion dollar machine, but they got used by criminal gangs to launder fake “science” as something real.

Things are so bad, fake scientists pay professional cheating services who use AI to create papers and torture the words so they look “original”. Thus a paper on “breast cancer” becomes a discovery about “bosom peril” and a “naïve Bayes” classifier became a “gullible Bayes”. An ant colony was labeled an “underground creepy crawly state”.

And what do we make of the flag to clamor ratio? Well, old fashioned scientists might call it “signal to noise”. The nonsense never ends.

A “random forest” is not always the same thing as an “irregular backwoods” or an “arbitrary timberland” — especially if you’re writing a paper on machine learning and decision trees.

The most shocking thing is that no human brain even ran a late-night Friday-eye over the words before they passed the hallowed peer review and entered the sacred halls of scientific literature. Even a wine-soaked third year undergrad on work experience would surely have raised an eyebrow when local average energy became “territorial normal vitality”. And when a random value became an “irregular esteem”. Let me just generate some irregular esteem for you in Python?

If there was such a thing as scientific stand-up comedy, we could get plenty of material, not by asking ChatGPT to be funny, but by asking it to cheat. Where else could you talk about a mean square mistake?

Wiley — a mega publisher of science articles has admitted that 19 journals are so worthless, thanks to potential fraud, that they have to close them down. And the industry is now developing AI tools to catch the AI fakes (makes you feel all warm inside?)

Fake studies have flooded the publishers of top scientific journals, leading to thousands of retractions and millions of dollars in lost revenue. The biggest hit has come to Wiley, a 217-year-old publisher based in Hoboken, N.J., which Tuesday will announce that it is closing 19 journals, some of which were infected by large-scale research fraud.

In the past two years, Wiley has retracted more than 11,300 papers that appeared compromised, according to a spokesperson, and closed four journals. It isn’t alone: At least two other publishers have retracted hundreds of suspect papers each. Several others have pulled smaller clusters of bad papers.

Although this large-scale fraud represents a small percentage of submissions to journals, it threatens the legitimacy of the nearly $30 billion academic publishing industry and the credibility of science as a whole.

January 12, 2024

“… normal people no longer trust experts to any great degree”

Theophilus Chilton explains why the imprimatur of “the experts” is a rapidly diminishing value:

One explanation for the rise of midwittery and academic mediocrity in America directly connects to the “everybody should go to college” mantra that has become a common platitude. During the period of America’s rise to world superpower, going to college was reserved for a small minority of higher IQ Americans who attended under a relatively meritocratic regime. The quality of these graduates, however, was quite high and these were the “White men with slide rules” who built Hoover Dam, put a man on the moon, and could keep Boeing passenger jets from losing their doors halfway through a flight. As the bar has been lowered and the ranks of Gender and Queer Studies programs have been filled, the quality of college students has declined precipitously. One recent study shows that the average IQ of college students has dropped to the point where it is basically on par with the average for the general population as a whole.

Another area where this comes into play is with the replication crisis in science. For those who haven’t heard, the results from an increasingly large number of scientific studies, including many that have been used to have a direct impact on our lives, cannot be reproduced by other workers in the relevant fields. Obviously, this is a problem because being able to replicate other scientists’ results is sort of central to that whole scientific method thing. If you can’t do this, then your results really aren’t any more “scientific” than your Aunt Gertie’s internet searches.

As with other areas of increasing sociotechnical incompetency, some of this is diversity-driven. But not wholly so, by any means. Indeed, I’d say that most of it is due to the simple fact that bad science will always be unable to be consistently replicated. Much of this is because of bad experimental design and other technical matters like that. The rest is due to bad experimental design, etc., caused by overarching ideological drivers that operate on flawed assumptions that create bad experimentation and which lead to things like cherry-picking data to give results that the scientists (or, more often, those funding them) want to publish. After all, “science” carries a lot of moral and intellectual authority in the modern world, and that authority is what is really being purchased.

It’s no secret that Big Science is agenda-driven and definitely reflects Regime priorities. So whenever you see “New study shows the genetic origins of homosexuality” or “Latest data indicates trooning your kid improves their health by 768%,” that’s what is going on. REAL science is not on display. And don’t even get started on global warming, with its preselected, computer-generated “data” sets that have little reflection on actual, observable natural phenomena.

“Butbutbutbut this is all peer-reviewed!! 97% of scientists agree!!” The latter assertion is usually dubious, at best. The former, on the other hand, is irrelevant. Peer-reviewing has stopped being a useful measure for weeding out spurious theories and results and is now merely a way to put a Regime stamp of approval on desired result. But that’s okay because the “we love science” crowd flat out ignores data that contradict their presuppositions anywise, meaning they go from doing science to doing ideology (e.g. rejecting human biodiversity, etc.). This sort of thing was what drove the idiotic responses to COVID-19 a few years ago, and is what is still inducing midwits to gum up the works with outdated “science” that they’re not smart enough to move past.

If you want a succinct definition of “scientism,” it might be this – A belief system in which science is accorded intellectual abilities far beyond what the scientific method is capable of by people whose intellectual abilities are far below being able to understand what the scientific method even is.

September 23, 2023

More on the history field’s “reproducibility crisis”

In the most recent edition of the Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes follows up on his earlier post about the history field’s efforts to track down and debunk fake history:

The concern I expressed in the piece is that the field of history doesn’t self-correct quickly enough. Historical myths and false facts can persist for decades, and even when busted they have a habit of surviving. The response from some historians was that they thought I was exaggerating the problem, at least when it came to scholarly history. I wrote that I had not heard of papers being retracted in history, but was informed of a few such cases, including even a peer-reviewed book being dropped by its publisher.

In 2001/2, University of North Carolina Press decided to stop publishing the 1999 book Designs against Charleston: The Trial Record of the Denmark Vesey Slave Conspiracy of 1822 when a paper was published showing hundreds of cases where its editor had either omitted or introduced words to the transcript of the trial. The critic also came to very different conclusions about the conspiracy. In this case, the editor did admit to “unrelenting carelessness“, but maintained that his interpretation of the evidence was still correct. Many other historians agreed, thinking the critique had gone too far and thrown “the baby out with the bath water“.

In another case, the 2000 book Arming America: The Origins of a National Gun Culture — not peer-reviewed, but which won an academic prize — had its prize revoked when found to contain major errors and potential fabrications. This is perhaps the most extreme case I’ve seen, in that the author ultimately resigned from his professorship at Emory University (that same author believes that if it had happened today, now that we’re more used to the dynamics of the internet, things would have gone differently).

It’s somewhat comforting to learn that retraction in history does occasionally happen. And although I complained that scholars today are rarely as delightfully acerbic as they had been in the 1960s and 70s in openly criticising one another, they can still be very forthright. Take James D. Perry in 2020 in the Journal of Strategy and Politics reviewing Nigel Hamilton’s acclaimed trilogy FDR at War. All three of Perry’s reviews are critical, but that of the second book especially forthright, including a test of the book’s reproducibility:

This work contains numerous examples of poor scholarship. Hamilton repeatedly misrepresents his sources. He fails to quote sources fully, leaving out words that entirely change the meaning of the quoted sentence. He quotes selectively, including sentences from his sources that support his case but ignoring other important sentences that contradict his case. He brackets his own conjectures between quotes from his sources, leaving the false impression that the source supports his conjectures. He invents conversations and emotional reactions for the historical figures in the book. Finally, he fails to provide any source at all for some of his major arguments

Blimey.

But I think there’s still a problem here of scale. It’s hard to tell if these cases are signs that history on the whole is successfully self-correcting quickly, or are stand-out exceptions. I was positively inundated with other messages — many from amateur historical investigators, but also a fair few academic historians — sharing their own examples of mistakes that had snuck past the careful scholars for decades, or of other zombies that refused to stay dead.

August 31, 2023

The sciences have replication problems … historians face similar issues

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the history profession’s closest equivalent to the ongoing replication crisis in the sciences:

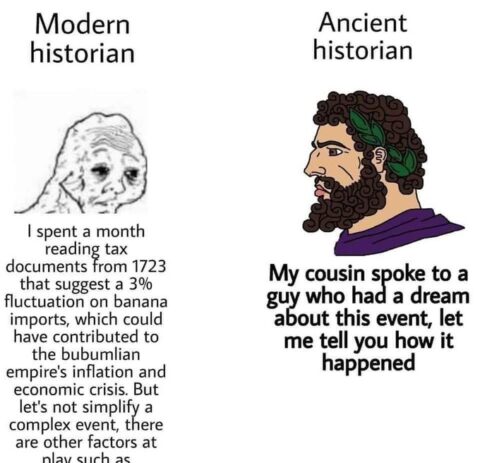

… I’ve become increasingly worried that science’s replication crises might pale in comparison to what happens all the time in history, which is not just a replication crisis but a reproducibility crisis. Replication is when you can repeat an experiment with new data or new materials and get the same result. Reproducibility is when you use exactly the same evidence as another person and still get the same result — so it has a much, much lower bar for success, which is what makes the lack of it in history all the more worrying.

Historical myths, often based on mere misunderstanding, but occasionally on bias or fraud, spread like wildfire. People just love to share unusual and interesting facts, and history is replete with things that are both unusual and true. So much that is surprising or shocking has happened, that it can take only years or decades of familiarity with a particular niche of history in order to smell a rat. Not only do myths spread rapidly, but they survive — far longer, I suspect, than in scientific fields.

Take the oft-repeated idea that more troops were sent to quash the Luddites in 1812 than to fight Napoleon in the Peninsular War in 1808. Utter nonsense, as I set out in 2017, though it has been cited again and again and again as fact ever since Eric Hobsbawm first misled everyone back in 1964. Before me, only a handful of niche military history experts seem to have noticed and were largely ignored. Despite being busted, it continues to spread. Terry Deary (of Horrible Histories fame), to give just one of many recent examples, repeated the myth in a 2020 book. Historical myths are especially zombie-like. Even when disproven, they just. won’t. die.

[…]

I don’t think this is just me being grumpy and pedantic. I come across examples of mistakes being made and then spreading almost daily. It is utterly pervasive. Last week when chatting to my friend Saloni Dattani, who has lately been writing a piece on the story of the malaria vaccine, I shared my

mounting paranoiahealthy scepticism of secondary sources and suggested she check up on a few of the references she’d cited just to see. A few days later and Saloni was horrified. When she actually looked closely, many of the neat little anecdotes she’d cited in her draft — like Louis Pasteur viewing some samples under a microscope and having his mind changed on the nature of malaria — turned out to have no actual underlying primary source from the time. It may as well have been fiction. And there was inaccuracy after inaccuracy, often inexplicable: one history of the World Health Organisation’s malaria eradication programme said it had been planned to take 5-7 years, but the sources actually said 10-15; a graph showed cholera pandemics as having killed a million people, with no citation, while the main sources on the topic actually suggest that in 1865-1947 it killed some 12 million people in British India alone.Now, it’s shockingly easy to make these mistakes — something I still do embarrassingly often, despite being constantly worried about it. When you write a lot, you’re bound to make some errors. You have to pray they’re small ones and try to correct them as swiftly as you can. I’m extremely grateful to the handful of subject-matter experts who will go out of their way to point them out to me. But the sheer pervasiveness of errors also allows unintentionally biased narratives to get repeated and become embedded as certainty, and even perhaps gives cover to people who purposefully make stuff up.

If the lack of replication or reproducibility is a problem in science, in history nobody even thinks about it in such terms. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of anyone systematically looking at the same sources as another historian and seeing if they’d reach the same conclusions. Nor can I think of a history paper ever being retracted or corrected, as they can be in science. At the most, a history journal might host a back-and-forth debate — sometimes delightfully acerbic — for the closely interested to follow. In the 1960s you could find an agricultural historian saying of another that he was “of course entitled to express his views, however bizarre.” But many journals will no longer print those kinds of exchanges, they’re hardly easy for the uninitiated to follow, and there is often a strong incentive to shut up and play nice (unless they happen to be a peer-reviewer, in which case some will feel empowered by the cover of anonymity to be extraordinarily rude).

May 21, 2017

“The conceptual penis as a social construct”

Getting a paper published is one of the regular measurements of academic life — usually expressed as “publish or perish” — so getting your latest work into print is a high priority for almost all academics. Some fields have rather … lower … standards for publishing than others. Peter Boghossian, Ed.D. (aka Peter Boyle, ED.D.) and James Lindsay, Ph.D. (aka Jamie Lindsay, Ph.D.) submitted a paper written in imitation of post-structuralist discursive gender theory and got it published in a peer-reviewed journal:

The androcentric scientific and meta-scientific evidence that the penis is the male reproductive organ is considered overwhelming and largely uncontroversial.

That’s how we began. We used this preposterous sentence to open a “paper” consisting of 3,000 words of utter nonsense posing as academic scholarship. Then a peer-reviewed academic journal in the social sciences accepted and published it.

This paper should never have been published. Titled, “The Conceptual Penis as a Social Construct,” our paper “argues” that “The penis vis-à-vis maleness is an incoherent construct. We argue that the conceptual penis is better understood not as an anatomical organ but as a gender-performative, highly fluid social construct.” As if to prove philosopher David Hume’s claim that there is a deep gap between what is and what ought to be, our should-never-have-been-published paper was published in the open-access (meaning that articles are freely accessible and not behind a paywall), peer-reviewed journal Cogent Social Sciences. (In case the PDF is removed, we’ve archived it.)

Assuming the pen names “Jamie Lindsay” and “Peter Boyle,” and writing for the fictitious “Southeast Independent Social Research Group,” we wrote an absurd paper loosely composed in the style of post-structuralist discursive gender theory. The paper was ridiculous by intention, essentially arguing that penises shouldn’t be thought of as male genital organs but as damaging social constructions. We made no attempt to find out what “post-structuralist discursive gender theory” actually means. We assumed that if we were merely clear in our moral implications that maleness is intrinsically bad and that the penis is somehow at the root of it, we could get the paper published in a respectable journal.

This already damning characterization of our hoax understates our paper’s lack of fitness for academic publication by orders of magnitude. We didn’t try to make the paper coherent; instead, we stuffed it full of jargon (like “discursive” and “isomorphism”), nonsense (like arguing that hypermasculine men are both inside and outside of certain discourses at the same time), red-flag phrases (like “pre-post-patriarchal society”), lewd references to slang terms for the penis, insulting phrasing regarding men (including referring to some men who choose not to have children as being “unable to coerce a mate”), and allusions to rape (we stated that “manspreading,” a complaint levied against men for sitting with their legs spread wide, is “akin to raping the empty space around him”). After completing the paper, we read it carefully to ensure it didn’t say anything meaningful, and as neither one of us could determine what it is actually about, we deemed it a success.

H/T to Amy Alkon for the link.

October 31, 2016

Is the “Gold Standard” of peer review actually just Fool’s Gold?

Donna Laframboise points out that it’s difficult to govern based on scientific evidence if that evidence isn’t true:

We’re continually assured that government policies are grounded in evidence, whether it’s an anti-bullying programme in Finland, an alcohol awareness initiative in Texas or climate change responses around the globe. Science itself, we’re told, is guiding our footsteps.

There’s just one problem: science is in deep trouble. Last year, Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet, referred to fears that ‘much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue’ and that ‘science has taken a turn toward darkness.’

It’s a worrying thought. Government policies can’t be considered evidence-based if the evidence on which they depend hasn’t been independently verified, yet the vast majority of academic research is never put to this test. Instead, something called peer review takes place. When a research paper is submitted, journals invite a couple of people to evaluate it. Known as referees, these individuals recommend that the paper be published, modified, or rejected.

If it’s true that one gets what one pays for, let me point out that referees typically work for no payment. They lack both the time and the resources to perform anything other than a cursory overview. Nothing like an audit occurs. No one examines the raw data for accuracy or the computer code for errors. Peer review doesn’t guarantee that proper statistical analyses were employed, or that lab equipment was used properly. The peer review process itself is full of serious flaws, yet is treated as if it’s the handmaiden of objective truth.

And it shows. Referees at the most prestigious of journals have given the green light to research that was later found to be wholly fraudulent. Conversely, they’ve scoffed at work that went on to win Nobel prizes. Richard Smith, a former editor of the British Medical Journal, describes peer review as a roulette wheel, a lottery and a black box. He points out that an extensive body of research finds scant evidence that this vetting process accomplishes much at all. On the other hand, a mountain of scholarship has identified profound deficiencies.

July 17, 2014

Peer review fraud – the tip of the iceberg?

Robert Tracinski points out that the recent discovery of a “peer review and citation ring” for mere monetary gain illustrates that when much is at stake, the temptation to pervert the system can become overwhelming:

The Journal of Vibration and Control — not as titillating as it sounds; it’s an engineering journal devoted to how to control dangerous vibrations in machines and structures — just retracted 60 published papers because “a ‘peer review and citation ring’ was apparently rigging the review process to get articles published.”

The motive here is ordinary corruption. Employment and prestige in academia is usually based on the number of papers a professor has published in peer-reviewed journals. It’s a very rough gauge of whether a scientist is doing important research, and it’s the kind of criterion that appeals to administrators who don’t want to stick their noses out by using their own judgment. But it is obviously open to manipulation. In this case, a scientist in Taiwan led a ring that created fake online reviewers to lend their approval to each others’ articles and pump up their career prospects.

But if this is what happens when the motive is individual corruption, imagine how much greater the incentive is when there is also a wider ideological motive. Imagine what happens when a group of academics are promoting a scientific theory that not only advances their individual careers in the universities, but which is also a source of billions of dollars in government funding, a key claim for an entire ideological world view, an entrenched dogma for one side of the national political debate, and a quasi-religious item of faith whose advocates believe they are literally saving the world?

October 31, 2011

China’s increased output of scientific papers masks deeper problems

Colby Cosh linked to an interesting press release from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, which shows a surge in published papers from China, but a significant drop in the rate at which those papers are cited:

Chinese researchers published more than 1.2 million papers from 2006 to 2010 — second only to the United States but well ahead of Britain, Germany and Japan, according to data recently published by Elsevier, a leading international scientific publisher and data provider. This figure represents a 14 percent increase over the period from 2005 to 2009.

The number of published academic papers in science and technology is often seen as a gauge of national scientific prowess.

But these impressive numbers mask an uncomfortable fact: most of these papers are of low quality or have little impact. Citation per article (CPA) measures the quality and impact of papers. China’s CPA is 1.47, the lowest figure among the top 20 publishing countries, according to Elsevier’s Scopus citation database.

China’s CPA dropped from 1.72 for the period from 2005 to 2009, and is now below emerging countries such as India and Brazil. Among papers lead-authored by Chinese researchers, most citations were by domestic peers and, in many cases, were self-citations.

Being published is very important for sharing discoveries and advancing the careers of the scientists, but it’s more important that those publications be read and referenced by other scientists. Self-citations are akin to self-published works: it doesn’t guarantee that the work is useless, but it increases the chances that it is.

Perhaps worse than merely useless publication is the culture of corruption that has grown up around the scientific community:

In China, the avid pursuit of publishing sometimes gives rise to scientific fraud. In the most high-profile case in recent years, two lecturers from central China’s Jinggangshan University were sacked in 2010 after a journal that published their work admitted 70 papers they wrote over two years had been falsified.

[. . .]

A study done by researchers at Wuhan University in 2010 says more than 100 million U.S. dollars changes hands in China every year for ghost-written academic papers. The market in buying and selling scientific papers has grown five-fold in the past three years.

The study says Chinese academics and students often buy and sell scientific papers to swell publication lists and many of the purported authors never write the papers they sign. Some master’s or doctoral students are making a living by churning out papers for others. Others mass-produce scientific papers in order to get monetary rewards from their institutions.

September 12, 2011

The easy way to be come a celebrity scientist

Deevybee has the steps you need to take to become a TV science celebrity:

Maybe you’re tired of grotting away at the lab bench. Or finding it hard to get a tenured job. Perhaps your last paper was rejected and you haven’t the spirit to fight back. Do not despair. There is an alternative. The media are always on the look-out for a scientist who will fearlessly speak out and generate newsworthy stories. You can gain kudos as an expert, even if if you haven’t got much of a track record in the subject, by following a few simple rules.

Rule #1. Establish your credentials. You need to have lots of letters after your name. It doesn’t really matter what they mean, so long as they sound impressive. It’s also good to be a fellow of some kind of Royal Society. Some of these are rather snooty and appoint fellows by an exclusive election process, but it’s a little known fact that others require little more than a minimal indication of academic standing and will admit you to the fellowship provided you fill in a form and agree to pay an annual subscription.

December 10, 2009

QotD: Peer review

Too often these days when people want to use a scientific study to bolster a political position, they utter the phrase, “It was peer reviewed” like a magical spell to shut off any criticism of a paper’s findings.

Worse, the concept of “peer review” is increasingly being treated in the popular discourse as synonymous with “the findings were reproduced and proven beyond a shadow of a doubt.”

This is never what peer review was intended to accomplish. Peer review functions largely to catch trivial mistakes and to filter out the loons. It does not confirm or refute a paper’s findings. Indeed, many scientific frauds have passed easily through peer review because the scammers knew what information the reviewers needed to see.

Peer review is the process by which scientists, knowledgeable in the field a paper is published in, look over the paper and some of the supporting data and information to make sure that no obvious errors have been made by the experimenters. The most common cause of peer review failure arises when the peer reviewer believes that the experimenters either did not properly configure their instrumentation, follow the proper procedures or sufficiently document that they did so.

Effective peer review requires that the reviewers have a deep familiarity with the instruments, protocols and procedures used by the experimenters. A chemist familiar with the use of a gas-chromatograph can tell from a description whether the instrument was properly calibrated, configured and used in a particular circumstance. On the other hand, a particle physicist who never uses gas-chromatographs could not verify it was used properly.

Shannon Love, “No One Peer-Reviews Scientific Software”, Chicago Boyz, 2009-11-28

December 4, 2009

Don’t bother your pretty little heads about all this “science” stuff

The non-scientists among us (that’s you and you and you and . . .) should just take a pill, sit back, and stop trying to understand the science:

And history repeats itself with climate change. We tell you people of the imminent dangers from the earth warming, and what do you do? You mock us. You question our motives. People who can’t even convert Fahrenheit to Celsius try and tell us we did the science wrong. Now emails have leaked from the Climate Research Unit that apparently show that scientists were fixing the data and trying to suppress the scientific research of dissenters, and you people demand answers from us. I have one thing to say to that. How dare you!

You do not understand the first thing about climate research. Man-made global warming is settled science. Disaster is imminent. We know this. It is a fact. We don’t waste time on studies that say otherwise, the same way we don’t waste time on studies that assert that the earth is flat. We are very smart people, and when we say something is so, you should just accept it.

So you think what is in those emails is important? Well, what exactly do you know? Do you see the white lab coats we wear? That color symbolizes pure science. Were someone like you to wear one, within five minutes it would be stained with neon orange powdered cheese and wet with drool from you trying to comprehend the data sets people like me look at every day.

November 30, 2009

CRU’s fall from Mount Olympus

Andrew Orlowski finds the “shocked, shocked!” reactions to the Climate Research Unit’s systematic perversion of the scientific process to be a bit overdone:

Reading the Climategate archive is a bit like discovering that Professional Wrestling is rigged. You mean, it is? Really?

The archive — a carefully curated 160MB collection of source code, emails and other documents from the internal network of the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia — provides grim confirmation for critics of climate science. But it also raises far more troubling questions.

Perhaps the real scandal is the dependence of media and politicians on their academics’ work — an ask-no-questions approach that saw them surrender much of their power, and ultimately authority. This doesn’t absolve the CRU crew of the charges, but might put it into a better context.

[. . .]

The allegations over the past week are fourfold: that climate scientists controlled the publishing process to discredit opposing views and further their own theory; they manipulated data to make recent temperature trends look anomalous; they withheld and destroyed data they should have released as good scientific practice, and they were generally beastly about people who criticised their work. (You’ll note that one of these is far less serious than the others.)

But why should this be a surprise?

Well, it’s quite understandable that the folks who’ve been pointing out the Emperor’s lack of clothing for the last few years are indulging in a fair bit of Schadenfreude . . . but it’s disturbing that the mainstream media are still trying to avoid discussing the issue as much as possible. This is close to a junk-science-based coup d’etat which would have had vast impact on the lives of most of the western world, and the media are still wandering away from the scene of the crime, saying, essentially “there’s nothing to see here, move along”.