The modern world stands on a cairn built by energy conversions in the past. Just as it took many loaves of bread and nosebags of hay to build Salisbury Cathedral, so it took many cubic metres of gas or puffs of wind to power the computer and develop the software on which I write these words. The Industrial Revolution was founded on the discovery of how to convert heat into work, initially via steam. Before that, heat (wood, coal) and work (oxen, people, wind, water) were separate worlds.

To be valuable, any conversion technology must produce reliable, just-in-time power that greatly exceeds — by a factor of seven and upwards — the amount of energy that goes into its extraction, conversion and delivery to a consumer. It is this measure of productivity, EROEI (energy return on energy invested), that limits our choice.

By the EROEI criterion, biofuel is a disastrous choice, requiring about as much tractor fuel to grow as you get out in ethanol or biodiesel. Wind power has a low energy return, because its vast infrastructure is energetically costly and needs replacing every two decades or so (sooner in the case of the offshore turbines whose blades have just expensively failed), while backing up wind with batteries and other power stations reduces the whole system’s productivity. Geothermal too may struggle, because turning warm water into electricity entails waste. Solar power with battery storage also fails the EROEI test in most climates. In the deserts of Arabia, where land is nearly free, sunlight abundant and gas cheap, solar power backed up with gas at night may be cheap.

Fossil fuels have amply repaid their energy cost so far, but the margin is falling as we seek gas and oil from tighter rocks and more remote regions. Nuclear fission passes the EROEI test with flying colours but remains costly because of ornate regulation.

Matt Ridley, “Nuclear Fusion Could Provide Unlimited Energy”, HumanProgress, 2018-04-09.

July 9, 2020

QotD: Energy return on energy invested

June 26, 2020

Progressive hate for nuclear power

In Quillette, Michael Shellenberger discusses the demands of some climate activists who also reject the best solutions to the problems they foresee:

For the last decade I have been obsessed with a question: Why are the people who are the most alarmist about environmental issues also opposed to all of the obvious solutions?

Those who raise the alarm about food shortages oppose expanding the use of chemical fertilizers, tractors, and GMOs. Those who raise the alarm about Amazon deforestation promote policies that fragment the forest. And those who raise the alarm about climate change oppose nuclear energy, the largest source of zero-emissions energy in developed nations. Why is that?

It is not an academic question for me. I have been a climate activist for 20 years and an energy expert for 10 of them. I was adamantly against nuclear energy until about a decade ago when it became clear renewables couldn’t replace fossil fuels. After educating myself about the facts, I came to support the technology.

Over the last five years, I have campaigned, as founder and president of my small and independent nonprofit research organization, Environmental Progress, to expand the use of nuclear energy. During that time our main opponents have not been climate skeptics or even the fossil fuel industry but rather other climate activists.

This is the case around the world. It is climate alarmist Democrats and Greens who are seeking to shut down nuclear plants in the US and Europe. Greta Thunberg last year condemned the technology as “extremely dangerous, expensive, & time-consuming,” which is false. And Green New Deal architect Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (AOC) has advocated closing the Indian Point nuclear plant in New York, which is now being replaced with natural gas.

In nearly every situation around the world, support for nuclear energy from climate activists like Thunberg and AOC would make the difference between nuclear plants staying open or closing, and being built or not being built. Had Thunberg spoken out in defense of nuclear power she likely could have prevented two reactors in her home nation of Sweden from being closed. Had AOC advocated for Indian Point rather than condemned it as dangerous, it could likely keep operating, for at least 40 years longer.

That’s because the main problem facing nuclear energy is that it’s unpopular — and far more among progressives than conservatives, and far more among women than men. There are no good technical or economic reasons that nations from the US and Japan to Sweden and Germany are closing their nuclear plants. Center-left governments are closing them early in response to the demands of progressives and Greens — the very same people who are claiming climate change will kill billions of people.

Some prominent environmental groups have a pecuniary interest in replacing existing nuclear generating stations with natural gas and “renewable” energy sources, but money isn’t the only reason for the widespread opposition to nuclear power:

Sierra Club, NRDC, and EDF have worked to shut down nuclear plants and replace them with fossil fuels and a smattering of renewables since the 1970s. They have created detailed reports for policymakers, journalists, and the public purporting to show that neither nuclear plants nor fossil fuels are needed to meet electricity demand, thanks to energy efficiency and renewables. And yet, as we have seen, almost everywhere nuclear plants are closed, or not built, fossil fuels are burned instead.

But it’s not just about money. It’s also about ideology. Anti-nuclear groups have long had a deeply ideological motivation to kill off nuclear energy.

Policymakers, journalists, conservationists, and other educated elites in the ’50s and ’60s knew that nuclear was unlimited energy and that unlimited energy meant unlimited food and water.

We could use desalination to convert ocean water into freshwater. We could create fertilizer without fossil fuels, by harvesting nitrogen from the air, and hydrogen from water, and combining them. We could create transportation fuels without fossil fuels, by taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere to make artificial hydrocarbons, or by splitting water to make pure hydrogen gas.

Nuclear energy thus created a serious problem for Malthusians — followers of widely-debunked 18th-century economist, Thomas Robert Malthus — who argued that the world was on the brink of ecological collapse and resource scarcity. Nuclear energy not only meant infinite fertilizer, freshwater, and food but also zero pollution and a radically reduced environmental footprint.

In reaction, Malthusians attacked nuclear energy as dangerous, mostly by suggesting that it would lead to nuclear war, but also by spreading misinformation about nuclear “waste” — the tiny quantity of used fuel rods — and the rapidly decaying radiation that escapes from nuclear plants during their worst accidents.

There is a pattern: Malthusians raise the alarm about resource depletion or environmental problems and then attack the obvious technical solutions. In the late 1700s, Thomas Malthus had to reject birth control to predict overpopulation. In the 1960s, Malthusians had to claim fossil fuels were scarce to oppose the extension of fertilizers and industrial agriculture to poor nations and to raise the alarm over famine. And today, climate activists reject nuclear energy in order to declare a coming climate apocalypse.

May 18, 2020

QotD: Science, evidence and “cognitive creationism”

I wrote about this problem in one of my Scientific American monthly columns recently, noting that both the Right and the Left distort science in the service of their ideology. On the Right we see the denial of evolution, vaccinations, stem cell research, and global warming. On the Left we see the distortion or denial of GMOs, nuclear power, genetic engineering, and evolutionary psychology, the latter of which I have called “cognitive creationism” for its endorsement of a blank slate model of the mind in which natural selection only operated on humans from the neck down.

What can we do about this problem? First, we must acknowledge that for most issues most conservatives and liberals are pro-science. Recent surveys show that over 90 percent of both Republicans and Democrats in the U.S., for example, agreed that “science and technology give more opportunities” and that “science makes our lives better.” In other words, anti-science attitudes are formed in very narrow cognitive windows — those in which science appears to oppose certain political or religious views. Knowledge of a subject helps a little. For example, those who know more about climate science are slightly more likely to accept that global warming is real and human-caused than those who know less on the subject. But that modest effect is not only erased when political ideology is factored in, it has an opposite effect on one end of the political spectrum. For Republicans, the more knowledge they have about climate science the less likely they are to accept the theory of anthropogenic global warming (while Democrats’ confidence goes up).

In another Scientific American column I wrote about this “backfire” effect, in which the more information you give someone that contradicts a cherished belief, the less likely they are to change their mind; in fact, they double-down on the belief. But this only applies to important political, religious, or ideological beliefs.

If you don’t have a dog in the fight then the facts can change your mind. But the cognitive dissonance created by facts counter to beliefs by which you define yourself will almost always be resolved by spin-doctoring the facts, not by changing your mind. Thus, when I engage in debate or conversation with creationists, for example, I don’t give them the choice between Darwin and Jesus, because I know who’s going to lose that one. Instead, I try to convince them that evolution was God’s way of creation, just like people in Newton’s time and after came to believe that gravity was God’s way of creating solar systems. I don’t believe that myself, of course, but the point is to get people to embrace science, not to win an argument. With climate deniers, I know from research and personal experience that when they hear “global warming” they think “anti-capitalism,” “anti-freedom,” “anti-American way of life.” So I take that off the table by showing them how investing in green technology is going to be one of the most lucrative enterprises in the history of capitalism. I call this the Elon Musk Model.

Michael Shermer, interviewed by Claire Lehmann, “The Skeptical Optimist: Interview with Michael Shermer”, Quillette, 2018-02-24.

May 26, 2019

HBO’s Chernobyl reviewed by Slava Malamud

Colby Cosh linked to Slava Malamud’s thread, rolled up here courtesy of Thread reader:

February 9, 2019

QotD: The global utility of a national carbon tax

James Griffin [of] Texas A&M’s Bush School of Government […] is a carbon-tax advocate who begins by acknowledging what everyone knows but hardly anyone says: that, absent subsidies and mandates, renewables and so-called green energy could not begin to compete with oil and coal, and the market would be entirely dominated by fossil fuels.

The carbon tax is one of those policy ideas that is largely sound in theory but runs up hard upon the shoals of reality. I am not convinced that a national carbon tax would change U.S. consumer behavior to such an extent that it would have positive effects on what is after all a global phenomenon, nor am I convinced that the U.S. government would use the revenue from a carbon tax to invest in real climate-change mitigation. That makes the carbon tax a very expensive way of demonstrating good intentions, which does not seem to me like a very fruitful way to work. And compared to more direct programs, such as clearing the way for the development of new, modern, nuclear-power facilities, a carbon tax is even less attractive.

Kevin D. Williamson, “The Case for a Carbon Tax”, National Review, 2017-03-08.

January 13, 2019

Canada’s role in India’s nuclear weapons development program

Canadian nuclear technology was critical to India for helping them develop their first nuclear weapons (although the Canadian reactor was supposed to be used only for civilian purposes):

Maybe you have heard the story of how India got the Bomb with Canada’s inadvertent help. We sold India a nuclear reactor called CIRUS in 1954 on an explicit promise that the facility would only be used for peaceful purposes. When India astonished the world with its first nuke test in May 1974, having upgraded the fuel output from CIRUS, it duly announced that it had successfully created a Peaceful Nuclear Explosive. The permanent consequence was, for better or worse, a nuclear-armed Subcontinent.

This is old news to enthusiasts of Cold War history. Here’s the new news: it almost happened twice. Canadian technology was almost used by another country to break into the nuclear club.

In November, historians David Albright and Andrea Stricker published a new book called Taiwan’s Former Nuclear Weapons Program: Nuclear Weapons On-Demand. The book pulls together the previously sketchy story of Nationalist China’s covert nuclear research, which had its roots in the postwar exodus of Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang party (KMT). Albright and Stricker describe decades of effort by the offshore Republic of China on Taiwan to play a double game with nuclear weapons.

At first Taiwan engaged in sneaky nuclear research — it turns out that if you research nuclear safety you learn a lot about nuclear explosions — and it tried to create a plutonium stockpile on the sly. But their scientists left too many clues: a plutonium-based nuke requires processed plutonium metal, and that is hard to make without raising suspicions. The Indian test of 1974 was an important wake-up call to the world, and the nonproliferation establishment and the U.S. Department of State started to get nervous about Taiwan.

After a 1977 confrontation with American officials, who could hardly be ignored by the vulnerable Republic of China, the KMT deep state tried subtler methods to create the “on-demand” weapon described in the title. Taiwan committed formally to nonproliferation and full U.S. inspections of their facilities, but sought to be able to make low-yield nukes within three to six months in the event of a Communist invasion from the mainland.

November 8, 2018

What do you do with decommissioned Royal Navy nuclear submarines?

Apparently, based on current MoD practice, you leave them sitting around for decades, until you have more decommissioned boats in storage than the RN has in commission:

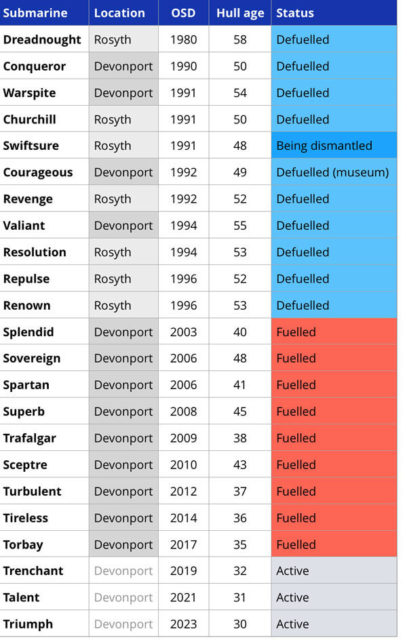

There are currently 20 former Royal Navy nuclear submarines awaiting disposal in Rosyth and Devonport. They do not represent a great hazard but maintaining them safely while they await dismantling is a growing drain on the defence budget. Nuclear submarines are arguably Britain’s most important defence assets but the failure to promptly deal with their legacy has been a national scandal. Although there has been discussion and consultation going back years, only recently has there been action to actually start the disposal process.

Status of Royal Navy submarine disposal in early 2018.

OSD – Out of Service Date. Hull age – years since hull laid down.

Plans for the safe and timely disposal of nuclear submarines should have been drawn up as far back as the 1970s but successive governments have avoided difficult decisions and handed the problem on to their successors. RN submarines were designed so the Reactor Pressure Vessel could be removed from the hull. Other nations cut the entire reactor compartment out of the submarine and transport it to land storage facilities. The US has successfully disposed of over 130 nuclear ships and submarines since the 1980s. The Russians have disposed of over 190 Soviet-era boats (with some international assistance) since the 1990s while France has already disposed of 3 boats from their much smaller numbers.The first Royal Navy nuclear submarine, HMS Dreadnought decommissioned in 1980, has now been tied up in Rosyth awaiting disposal longer than she was in active service.

As any householder knows, It is sensible practice to dispose of your worn out items before you replace them with new ones.

The capacity to store more boats at Devonport is limited, every further delay adds to cost that will have to come from a defence budget that is much smaller in real terms than when the boats were conceived at the height of the Cold War. Apart from the attraction of deferring costs in the short-term, a major cause of delay has been the selection of a land storage site for the radioactive waste. It has also taken time to develop a method and ready the facilities needed to undertake the dismantling project.

Afloat storage

While awaiting dismantling, decommissioned submarines are stored afloat in a non-tidal basin in the dockyard [as seen in the image at the top of this post]. Classified equipment, stores and flammable materials are removed together with rudders, hydroplanes and propellers while the hull is given treatments to help preserve its life. The 7 submarines in Rosyth have all had their nuclear fuel rods removed but of the 13 in Devonport, 9 are still fuelled. This is because in 2003 the facilities for de-fuelling were deemed no longer safe enough to meet modern regulation standards and the process was halted. Submarines that have not had their fuel rods removed have the reactor primary circuit chemically treated to guarantee it remains inert and additional radiation monitoring equipment is fitted.

More than £16m was spent between 2010-15 just to maintain these old hulks alongside, and costs are rising. Apart from regular monitoring, the hulks need to be hauled out of the basin for occasional dry docking for inspection and repainting to protect the hull from corrosion. All this effort and expense is a drain on precious resources for no direct gain. Responsible care of the growing number of hulls means they pose little risk to the local population, but a tiny risk does remain. This makes some people living nearby uneasy and provides another grievance for those ideologically opposed to nuclear submarines and Trident.

March 15, 2017

Using the Banana Equivalent Dose (BED) to measure hysteria in media reports on radiation

It’s quite common to find media reports involving radiation that are heavy on the freak-out factor and light on the facts. Here’s an interesting and useful rule of thumb you can use … in the few cases that the reports actually provide any meaningful figures on radioactivity:

Long-time readers know that very useful measures of both radioactivity and radiation dose rates are the Banana Equivalent Dose (BED), and a similar measure I think I invented (because no one else ever bothered) called the Banana Equivalent Radioactivity (BER). (The units here are explained in my old article “Understanding Radiation.”)

Bananas are useful for these measures because bananas concentrate potassium, and a certain amount of that potassium is ⁴⁰K, which is naturally radioactive. The superscript “40” there is the atomic number, or the number of protons in the nucleus, of that particular potassium (symbol K) isotope. Because of that potassium content, bananas are mildly radioactive: a medium banana at around 150g emits about 1 micro-Sievert per hour (1 µSv/hr) and contains about 15 Becquerel (15 Bq) of radioactive material.

(Why bananas? There are a lot of plant-based foods that concentrate potassium. It is, however, an essential rule of humor that bananas are the funniest fruit.)

Our radioactive boars are considered unfit at 600 Bq per kilogram. So, a tiny bit of arithmetic [(1000 g/kg)/150 g/banana × 15 Bq/banana] gives us 100 Bq/kg for bananas. All right, so this boar meat has 6 times as much radioactivity as a banana. Personally, this wouldn’t worry me.

So let’s turn to the radioactivity detected off the Oregon coast. This is 0.3 Bq per cubic meter. Conveniently — the joys of metric — one cubic meter of water is one metric tonne is 1000 liters is 1000 kilograms, so the radiation content here is .0003 Bq/kg.

15/0.0003 is 50,000. So, bananas have 50,000 times more radiation than the seawater being reported.

February 13, 2017

“[M]ost of what journalists know about radioactivity came from watching Godzilla“

Charlie Martin explains why the “news” out of Fukushima lately has been mostly unscientific hyperventilation and bloviation:

On February 8, Adam Housley of Fox News reported a story with a terrifying headline: “Radiation at Japan’s Fukushima Reactor Is Now at ‘Unimaginable’ Levels.” Let’s just pick up the most exciting paragraphs:

The radiation levels at Japan’s crippled Fukushima nuclear power plant are now at “unimaginable” levels.

[Housley] said the radiation levels — as high as 530 sieverts per hour — are now the highest they’ve been since 2011 when a tsunami hit the coastal reactor.

“To put this in very simple terms. Four sieverts can kill a handful of people,” he explained.

The degree to which this story is misleading is amazing, but to explain it, we need a little bit of a tutorial.

The Touhoku earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011, along with all the other damage they caused, knocked out the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi (“plant #1”) and Daini (“plant #2”) reactors. Basically, the two reactors were hit with a 1000-year earthquake and a 1000-year tsunami, and the plants as built weren’t able to handle it.

Both reactors failed, and after a sequence of unfortunate events, melted down. I wrote quite a lot about it at the time; bearing in mind this was early in the story, my article from then has a lot of useful information.

[…]

So what have we learned today?

We learned that inside the reactor containment at Fukushima Daini, site of the post-tsunami reactor accident, it’s very very radioactive. How radioactive? We don’t know, because the dose rate has been reported in inappropriate units — Sieverts are only meaningful if someone is inside the reactor to get dosed.

Then we learned that the Fukushima accident is leaking 300 tons of radioactive water — but until we dig into primary sources, we didn’t learn the radioactive water is very nearly clean enough to be drinking water. So what effect does this have on the ocean, as Housley asks? None.

The third thing we learned — and I think probably the most important thing — is to never trust a journalist writing about anything involving radiation, the metric system, or any arithmetic more challenging than long division.

August 5, 2015

A report on phasing out nuclear power in Sweden

It may make politicians and activists feel empowered and righteous, but it has negative aspects that don’t seem to get the same level of attention as the “feel good” rhetoric does:

Nuclear power faces an uncertain future in Sweden. Major political parties, including the Green party of the coalition-government have recently strongly advocated for a policy to decommission the Swedish nuclear fleet prematurely. Here we examine the environmental, health and (to a lesser extent) economic impacts of implementing such a plan. The process has already been started through the early shutdown of the Barsebäck plant. We estimate that the political decision to shut down Barsebäck has resulted in ~2400 avoidable energy-production-related deaths and an increase in global CO2 emissions of 95 million tonnes to date (October 2014). The Swedish reactor fleet as a whole has reached just past its halfway point of production, and has a remaining potential production of up to 2100 TWh. The reactors have the potential of preventing 1.9–2.1 gigatonnes of future CO2-emissions if allowed to operate their full lifespans. The potential for future prevention of energy-related-deaths is 50,000–60,000. We estimate an 800 billion SEK (120 billion USD) lower-bound estimate for the lost tax revenue from an early phase-out policy. In sum, the evidence shows that implementing a ‘nuclear-free’ policy for Sweden (or countries in a similar situation) would constitute a highly retrograde step for climate, health and economic protection.

May 5, 2014

Fukushima, radiation, and FUD

James Conca on a recent UN report that isn’t getting attention:

It’s always amazing when a United Nations report that has global ramifications comes out with little fanfare. The latest one states that no one will get cancer or die from radiation released from Fukushima, but the fear and overreaction is harming people (UNIS; UNSCEAR Fukushima; UNSCEAR A-68-46 [PDF]). This is what we’ve been saying for almost three years but it’s nice to see it officially acknowledged.

According to the report, drafted last year but only recently finalized by the U.N., “The doses to the general public, both those incurred during the first year and estimated for their lifetimes, are generally low or very low. No discernible increased incidence of radiation-related health effects are expected among exposed members of the public or their descendants. The most important health effect is on mental and social well-being, related to the enormous impact of the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident, and the fear and stigma related to the perceived risk of exposure to ionizing radiation. Effects such as depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms have already been reported.”

In addition, the report states, “Increased rates of detection of [thyroid] nodules, cysts and cancers have been observed during the first round of screening; however, these are to be expected in view of the high detection efficiency [using modern high-efficiency ultrasonography]. Data from similar screening protocols in areas not affected by the accident imply that the apparent increased rates of detection among children in Fukushima Prefecture are unrelated to radiation exposure.”

So the Japanese people can start eating their own food again, and moving back into areas contaminated with radiation levels similar to many areas of the world like Colorado and Brazil, which includes most of the exclusion zone. Only a few places shouldn’t be repopulated.

But if you want to continue feeling afraid, and want to make sure others keep being afraid, by all means ignore this report on Fukushima. But then you really can’t keep quoting previous UNSCEAR policy and application of LNT (the Linear No-Threshold dose hypothesis) to support more fear.

Note – LNT is a leftover Cold War ideology that states all radiation is bad, even the background radiation we are bathed in every day, even the 3,200 pCi of radiation in a bag of potato chips (yes, potato chips have the most radioactivity of any food, but they taste sooo good!).

Of course, if you’ve been actually following the events from three years back, this report will contain few surprises.

July 5, 2013

And now, a five-minute sales pitch for Thorium nuclear reactors

A short video of Kirk Sorensen taking us through the benefits of Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactors, a revolutionary liquid reactor that runs not on uranium, but thorium. These work and have been built before. Search for either LFTRs or Molten Salt Reactors (MSR).

FAQ

The main downsides/negatives to this technology, politics, corrosion and being scared of nuclear radiation. Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactors were created 50 years ago by an American chap named Alvin Weinberg, but the American Government realised you can’t weaponise the by-products and so they weren’t interested.Another point, yes it WAS corrosive, but these tests of this reactor were 50 years ago, our technology has definitely improved since then so a leap to create this reactor shouldn’t be too hard.

And nuclear fear is extremely common in the average person, rather irrational though it may be. More people have died from fossil fuels and even hydroelectric power than nuclear power. I added this video for a project regarding Liquid Fluoride Thorium Reactors, watch and enjoy.

No, it would not collapse the economy… just like the use of uranium reactors didn’t… neither did coal… This is because you wouldn’t have an instant transition from coal… oil… everything else to thorium. We could not do that. Simply due to the engineering. Give it 50 years we might be using thorium instead of coal/oil (too late in terms of global warming, but that’s another debate completely), but we certainly won’t destroy the earths economy. Duh.

And yes he said we’d never run out. Not strictly true… bloody skeptics … LFTRs can harness 3.5 million Kwh per Kg of thorium! 70 times greater than uranium, 10,000 greater than oil… and there is over 2.6 million tonnes of it on earth… Anyone with a calculator, or a brain, will understand that is a lot of energy!!

H/T to Rob Fisher for the link.

December 19, 2012

Not all submarines are equal

Strategy Page on the US Navy’s need to work with — and even consider buying — modern diesel-electric submarines:

The U.S. Navy continues to debate the issue of just how effective non-nuclear submarines would be in wartime, and whether the U.S. should buy some of these non-nuclear boats itself. This radical proposal is based on two compelling factors. First, the U.S. Navy may not get enough money to maintain a force of 40-50 SSNs (attack subs.) Second, the quietness of modern diesel-electric boats puts nuclear subs at a serious disadvantage, especially in coastal waters. With modern passive sensors, a submerged diesel-electric sub is often the best weapon for finding and destroying other diesel-electric boats. While the nuclear sub is the most effective high seas vessel, especially if you have worldwide responsibilities and these nukes would have to quickly move long distances to get to the troubled waters, the diesel electric boat, operating on batteries in coastal waters, is quieter and harder to find.

[. . .]

For much of the past decade the U.S. Navy has been trying to get an idea of just how bad the threat it. Thus from 2005 to 2007 the United States leased a Swedish sub (Sweden only has five subs in service), and its crew, to help American anti-submarine forces get a better idea of what they were up against. This Swedish boat was a “worst case” scenario, an approach that is preferred for training. The Gotland class Swedish subs involved are small (1,500 tons, 64.5 meters/200 feet long) and have a crew of only 25. The Gotland was based in San Diego, along with three dozen civilian technicians to help with maintenance.

For many years before the Gotland arrived, the U.S. Navy had trained against Australian diesel-electric subs, and often came out second. The Gotland has one advantage over the Australian boats, because of its AIP system (which allows it to stay under water, silently, for several weeks at a time). Thus the Gotland is something of a worst case in terms of what American surface ships and submarines might have to face in a future naval war. None of America’s most likely naval opponents (China, North Korea or Iran), have AIP boats yet, but they do have plenty of diesel-electric subs which, in the hands of skilled crews, can be pretty deadly.

December 2, 2012

USS Enterprise, the first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, decommissioned

The USS Enterprise was taken out of service yesterday after a long career:

The world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier was retired from active service on Saturday, temporarily reducing the number of carriers in the U.S. fleet to 10 until 2015.

The USS Enterprise ended its notable 51-year career during a ceremony at its home port at Naval Station Norfolk, where thousands of former crew members, shipbuilders and their families lined a pier to bid farewell to one of the most decorated ships in the Navy.

“It’ll be a special memory. I’ve missed the Enterprise since every day I walked off of it,” said Kirk McDonnell, a former interior communications electrician aboard the ship from 1983 to 1987 who now lives in Highmore, S.D.

H/T to Doug Mataconis for the link. He also reported that the Secretary of the Navy announced that the third Ford class carrier will be called Enterprise.

August 17, 2012

The plight of Russian submariners

An update from Strategy Page on how far the Russian nuclear submarine threat has diminished from its peak during the cold war:

Three years ago two Akulas were detected (by the U.S. Navy) off the east coast of the United States, in international waters. Russia admitted two of its Akula class boats were out there. This was the first time Russian subs had been off the North American coast in over a decade. This spotlights something the Russian admirals would rather not dwell on. The Russian Navy has not only shrunk since the end of the Cold War in 1991, but it has also become much less active. In the previous three years, only ten of their nuclear subs had gone to sea, on a combat patrol, each year. Most of the boats going to sea were SSNs, the minority were SSBNs (ballistic missile boats). There were often short range training missions, which often lasted a few days, or just a few hours.

The true measure of a fleet’s combat ability is the number of “combat patrols” or “deployments” in makes in a year and how long they are. In the U.S. Navy, most of these last from 2-6 months. Currently U.S. nuclear subs have carry out ten times as many patrols as their Russian counterparts. Russia is trying to catch up, but has a long way to go.

Russia has only 14 SSNs (nuclear attack subs) in service and eight of them are 7,000 ton, Akulas. These began building in the late 1980s and are roughly comparable to the American Los Angeles class. All of the earlier Russian SSNs are trash, and most have been decommissioned. There are also eight SSGN (nuclear subs carrying cruise missiles) and 20 diesel electric boats. There is a new class of SSGNs under construction, but progress has been slow.

[. . .]

The peak year for Russian nuclear sub patrols was 1984, when there were 230. That number rapidly declined until, in 2002, there were none. Since the late 1990s, the Russian navy has been hustling to try and reverse this decline. But the navy budget, despite recent increases, is not large enough to build new ships to replace the current Cold War era fleet that is falling apart. The rapid decline of Russia’s nuclear submarine fleet needed international help to safely decommission over a hundred obsolete, worn out, defective or broken down nuclear subs. This effort has been going on for over a decade, and was driven by the Russian threat to just sink their older nuclear subs in the Arctic Ocean. That might work with conventional ships, but there was an international uproar over what would happen with all those nuclear reactors sitting on the ocean floor forever. Russia generously offered to accept donations to fund a dismantling program that included safe disposal of the nuclear reactors.