The most frequently assigned book on science in universities (aside from a popular biology textbook) is Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. That 1962 classic is commonly interpreted as showing that science does not converge on the truth but merely busies itself with solving puzzles before lurching to some new paradigm that renders its previous theories obsolete; indeed, unintelligible. Though Kuhn himself disavowed that nihilist interpretation, it has become the conventional wisdom among many intellectuals. A critic from a major magazine once explained to me that the art world no longer considers whether works of art are “beautiful” for the same reason that scientists no longer consider whether theories are “true.” He seemed genuinely surprised when I corrected him.

The historian of science David Wootton has remarked on the mores of his own field: “In the years since Snow’s lecture the two-cultures problem has deepened; history of science, far from serving as a bridge between the arts and sciences, nowadays offers the scientists a picture of themselves that most of them cannot recognize.” That is because many historians of science consider it naïve to treat science as the pursuit of true explanations of the world. The result is like a report of a basketball game by a dance critic who is not allowed to say that the players are trying to throw the ball through the hoop.

Many scholars in “science studies” devote their careers to recondite analyses of how the whole institution is just a pretext for oppression. An example is a 2016 article on the world’s most pressing challenge, titled “Glaciers, Gender, and Science: A Feminist Glaciology Framework for Global Environmental Change Research,” which sought to generate a “robust analysis of gender, power, and epistemologies in dynamic social-ecological systems, thereby leading to more just and equitable science and human-ice interactions.”

More insidious than the ferreting out of ever more cryptic forms of racism and sexism is a demonization campaign that impugns science (together with the rest of the Enlightenment) for crimes that are as old as civilization, including racism, slavery, conquest, and genocide.

This was a major theme of the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School, the quasi-Marxist movement originated by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, who proclaimed that “the fully enlightened earth radiates disaster triumphant.” It also figures in the works of postmodernist theorists such as Michel Foucault, who argued that the Holocaust was the inevitable culmination of a “bio-politics” that began with the Enlightenment, when science and rational governance exerted increasing power over people’s lives. In a similar vein, the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman blamed the Holocaust on the Enlightenment ideal to “remake the society, force it to conform to an overall, scientifically conceived plan.”

In this twisted narrative, the Nazis themselves are somehow let off the hook (“It’s modernity’s fault!”). Though Critical Theory and postmodernism avoid “scientistic” methods such as quantification and systematic chronology, the facts suggest that they have the history backwards. Genocide and autocracy were ubiquitous in premodern times, and they decreased, not increased, as science and liberal Enlightenment values became increasingly influential after World War II.

Steven Pinker, “The Intellectual War on Science”, Chronicle of Higher Education, 2018-02-13.

April 18, 2020

QotD: Distorting the history of science

September 13, 2018

QotD: “God is dead”

The life and work of the maverick German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) is associated with five interlinking ideas: the death of God; nihilism and the crisis in morality; the Superman; the will to power; and the eternal recurrence.

Nietzsche first announced that ‘God is dead’ in his 1883 work The Joyful Science. As with much that he wrote, this phrase of Nietzsche’s has subsequently been often misunderstood. Taken literally, it is obviously a nonsensical declaration, for either a Christian god is real and eternal, or else he never existed in the first place. What Nietzsche meant by the death of God was that European civilisation had lost its faith in Christianity, but was still living by values and a morality system based on it. For this reason he believed European civilisation was facing a crisis resulting from the approaching collapse in its morality system, and the dawn of the age of nihilism – hence the title of his 1886 work, Beyond Good and Evil, which was not the libertine manifesto it sounds like, but a contention that Christian values of good and evil have become redundant.

In this respect, Nietzsche was not a nihilist, another common misconception. He viewed the coming age of nihilism with much trepidation, fearing (rightly) that the result would be great wars in the 20th century. He believed that it was imperative that humanity create a new morality system for the coming post-Christian age. The solution, he believed, was a new individualistic morality system in which the strongest, bravest men would become their own masters and creators, and in turn would become philosopher kings and oligarchs of the spirit. This new man was to be embodied in his infamous, hypothetical Übermensch, or Superman (as Über means above and beyond in German, Nietzsche’s word used to be also translated as the Beyond-Man or Overman, but today is usually not translated at all. The Übermensch goes above and beyond.)

Patrick West, “Nietzsche and the struggle against nihilism”, Spiked, 2018-08-03.

August 23, 2018

QotD: Nietzsche’s idealised Übermensch

The solution, [Nietzsche] believed, was a new individualistic morality system in which the strongest, bravest men would become their own masters and creators, and in turn would become philosopher kings and oligarchs of the spirit. This new man was to be embodied in his infamous, hypothetical Übermensch, or Superman (as Über means above and beyond in German, Nietzsche’s word used to be also translated as the Beyond-Man or Overman, but today is usually not translated at all. The Übermensch goes above and beyond.)

The arch-individual, non-conformist Superman rises above the morality of the herd and harnesses all of his internal energies, all the energy within – his ‘will to power’, which consists of his sexual drive, survival drive, pleasure drive and other non-rational forces – to embrace life fearlessly, and with nobility and courage. The ultimate task of the Übermensch is to face life and live it as if he had lived it an infinite number of times in the past, and will do so an infinite number of times in the future. In so doing he will accept all of life’s horrors and sufferings in a kind of neverending Groundhog Day. Nietzsche ostensibly took this ‘eternal recurrence’ to be literally true, not just a metaphor.

All of these thoughts were developed by Nietzsche in the third stage of his writing. The first stage, from 1872 to 1878, was marked by a preoccupation with the pre-Socratic Ancient Greeks, and how they used art and theatre to make sense of human existence and all its capricious cruelties. The second stage, encompassing the books Human, All Too Human (1878), The Dawn (1881) and The Joyful Science (1883), was marked by experimental and doubtful musings on the notion of truth. While his third and final stage, taking us up to January 1889, when he was struck down by madness, is characterised chiefly by the question of morality, and how his idealised Übermensch would confront and overcome nihilism.

Patrick West, “Nietzsche and the struggle against nihilism”, Spiked, 2018-08-03.

October 30, 2016

QotD: Hunter S. Thompson’s nihilism

Of course in [Hunter S.] Thompson’s world the Big Darkness is always coming. Every day it doesn’t come means it’ll just be bigger and darker when it finally arrives. He’s the anti-rooster, bitching about the dawn: sure, it worked today, but one of these days the sun won’t come up, and then where will you be? Sitting on your nest popping out eggs like THEY want you to, completely unprepared for the Big Darkness! Which will be huge! And dark!

It would be funny if it was, well, funny, but it’s not even that. It’s just rote spew from the other side of the latter sixties. You had your Hopeful Hippies, the face-painters and daisy-strewers, convinced that human nature and human history could be irrevocably changed if we all held hands, listened to “Imagine” and realized that the war is not the answer. Regardless of the question. But the other side was the sort of dank twitchy nihilism Thompson spouts. It has no lessons, no morals, no hope. Imagine, Winston, that the future consists of a boot pressing on a face. Here’s the worst part, Winston — inside the boot is NIXON’S FOOT.

Thompson has less hope than the Islamists; at least they have an afterlife to look forward to. All we have is a country so rotten and exhausted it’s not worth defending. It never was, of course, but it’s even less defensible now than before.

He can say what he wants. Drink what he wants. Drive where he wants. Do what he wants. He’s done okay in America. And he hates this country. Hates it. This appeals to high school kids and collegiate-aged students getting that first hot eye-crossing hit from the Screw Dad pipe, but it’s rather pathetic in aged moneyed authors. And it would be irrelevant if this same spirit didn’t infect on whom Hunter S. had an immense influence. He’s the guy who made nihilism hip. He’s the guy who taught a generation that the only thing you should believe is this: don’t trust anyone who believes anything. He’s the patron saint of journalism, whether journalists know it or not.

James Lileks, Bleat, 2004-05-17.

October 31, 2015

QotD: Modern movies fail to reflect reality in the expected manner … unexpectedly

Ages are marked by their paranoias and despairs, and we see those paranoias and despairs in the art an age produces. What we dread in earnest we enjoy in fantasy.

After Watergate, there were a series of very paranoid and nihilistic films — The Parallax View, Capricorn One, The Conversation on the paranoid end; then all the violent ones about a growing nihilism in the world — Dirty Harry, Death Wish, and so on.

Cultural observers had no problem pointing directly at Watergate (and the assassinations of the Kennedys and Martin Luther King, Jr.) to explain the paranoia, and nor were they so blind as to not notice the decay and malaise (and rising tide of bloody crime) of the seventies were responsible for the various violent retribution films.

[…]

Since 9/11, we faced a lot of movies about cataclysm and the end of the world. It’s easy enough to see that connection.

But the Age of Obama has not produced any uplift, nor any respite from the current preoccupation of people with the End Times. As a non-religious person, I don’t mean this literally (though many may), but it is impossible not to note the idea of Apocalypse and Cataclysm is in the air.

Look at the number of zombie films and zombie TV shows — as obvious a metaphor for decay and rot as can be imagined. Or the still-doing-bonzo-business cataclysm fantasies. Even the latest Man of Steel was about cataclysm.

And now add into that the large number of paranoid, rotten dystopia movies.

If the Age of Obama is so swell, if we’re all filled with Hope, why is this age not producing the spate of feel-good, have-fun, get-rich movies the 80s did?

Why are our collective fantasies in the Age of Obama so single-mindedly focused on the idea of dystopia, cultural decay, and ultimately cultural destruction?

Whether liberal cultural critics want to admit it or not — and they seem very much to not want to admit it, because this is so obvious it’s painful, and yet they fail to make this obvious connection — the Obama years are years of economic want, emotional depression, and spiritual chaos, at least as reflected by entertainments resolutely focusing on the end-times and the wretched dystopias that arise after the End Times, when civilization is dead but just hasn’t stopped moving yet.

The Leftovers, The Returned, Revolution, the Walking Dead not only being a top-rated show, but spawning a top-rated spin-off — I dare anyone to find any previous moment in American history, including in the years of paranoia after Watergate, in which our fantasies have been so dark, depressive, anxious and foreboding.

This is all very obvious. The people in Hollywood turning out one cataclysm-and-dystopia entertainment after another surely sense this, as do the talentless idiots paid to comment on the culture at fluffy magazines like The Atlantic and New York and The New Yorker; and yet, another aspect of the Age of Obama — that one must never admit the horrible truth; one must always pretend it away, and give only praise to Dear Leader — keeps people from stating what is so obvious it’s increasingly uncomfortable to remain silent about it.

Ace, “Going By Movies, America Is In An Apocalyptic Frame of Mind”, Ace of Spades H.Q., 2015-10-27.

May 2, 2015

QotD: The nihilism of modern art

One of my earliest blog essays (Terror Becomes Bad Art) was about Luke Helder, the pipe-bombing “artist” who created a brief scare back in 2002. Arguably more disturbing than Helder’s “art” was the fact that he genuinely thought it was art, because none of the supposed artists or arts educators he was in contact with had ever taught him any better and his own talent was not sufficient to carry him beyond their limits.

I am not the first to observe that something deeply sick and dysfunctional happened to the relationship between art, popular culture, and technology during the crazy century we’ve just exited. Tom Wolfe made the point in The Painted Word and expanded on it in From Bauhaus To Our House. Frederick Turner expanded the indictment in a Wilson Quarterly essay on neoclassicism which, alas, seems not to be available on line.

If we judge by what the critical establishment promotes as “great art”, most of today’s artists are bad jokes. The road from Andy Warhol’s soup cans to Damien Hirst’s cows in formaldehyde has been neither pretty nor edifying. Most of “fine art” has become a moral, intellectual, and esthetic wasteland in which whatever was originally healthy in the early-modern impulse to break the boundaries of received forms has degraded into a kind of numbed-out nihilism.

[…]

To see these craft objects, unashamedly made for money (that’ll be $40 extra for molecular-surface etching, thank you), is to have your nose rubbed in the desperate poverty of most modern art, to be reminded of the vacuum at its core and the pathetic Luke Helders that the vacuum spawns. It’s a poverty of meaning, a parochialism that insists that the only interesting things in the universe are the artist’s own psychological and political quirks.

Bathsheba Grossman’s art reminds us that exploration of the narrow confines of an artist’s head is a poor substitute for artistic exploration of the universe. It reminds us that what the artist owes his audience is beauty and discovery and a sense of connection, not alienation and ugliness and neurosis and political ax-grinding.

Forgetting this value rotted the core out of the fine arts and literary fiction of the 20th century. We can hope, though, that artists like her and Arthur Ganson will show the way forward to remembering it. Only in that way will the unhealthy chasm between popular and fine art be healed, and fine art be restored to a healthy and organic relationship with culture as a whole.

Eric S. Raymond, “The Art of Science”, Armed and Dangerous, 2004-09-21.

June 30, 2010

The CCLA weighs in

Clive sent me an email this morning, with a link to the preliminary report from the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, saying:

The fourth paragraph of the Executive summary ends with a cautionary note about the police chasing after 100-150 protester and in the process disregarding the rights of thousands.

My thought was, what do you expect. In Ontario we let the police do this ALL the time. We encourage it. We even applaud it. It is called RIDE.

This is just the next logical step.

The police demonstrated a bipolar attitude to the disturbances, with the “good cop” sitting back on Saturday and letting the nihilists get away with all sorts of property damage (including three police cruisers), while the “bad cop” showed up later on, like the punchline to a Monty Python skit, to arrest the bystanders (“Society is to blame.” “Right, we’ll arrest them instead!”).

June 28, 2010

Running with the nihilists

Tony Keller walked with the main union-led protest marchers on Saturday, pointing out that there was no single, unifying principle — it was a “grievance smorgasbord, an all-you-can-eat buffet of complaints, and apparently anyone protesting anything — anything — was invited”. What interested him the most, however, were the “hobbits”:

Standing in front of Cafe Lettieri, which was still open and doing a booming business even as protesters were packed so tightly outside that they pressed up against its windows, I heard someone to my right say, “Black Bloc, meet up on Queen!”

I turned to see six hobbits in black hoodies shuffling past me. It was on. Whatever “it” was going to be.

[. . .]

And then the non-peaceful part of our program started. The crowd suddenly began to surge away from the police lines at Spadina and Richmond, and back onto Queen Street. We were now heading east, violently following the route the non-violent march had just taken. A mass of maybe 100 people in black hoodies and balaclavas was moving at almost a run, accompanied by several hundred journalists and riot tourists. Occasionally someone would dart out from the group to smash a window or spray paint a slogan: “Against Police Against Prisons,” “F– the Police,” “F- Corporate Rule.”

[. . .]

The hoodie people weren’t just small in number, they were also small in stature. A lot of skinny white boys. And white women. (Some skinny, some really not). They looked like the kind of people who spend a lot of time playing video games in their parents’ basements. Or the graduating class of an art college. They were not marauding toughs. More like marauding geeks. Geeks marauding in a spontaneous yet carefully choreographed manner.

There’s a point in most peoples’ lives when getting out and protesting seems like such a good idea. And then you graduate and get a job . . .

June 27, 2010

The stars were aligned for ugliness

Peter Kuitenbrouwer enumerates the reasons why the violence this weekend was pretty much inevitable:

Prime Minister Stephen Harper has something to answer for tonight. It is hard for this writer to escape the feeling that this summit was designed with every possible star aligned for ugliness to occur. The summit is held on a summer weekend, after university and high school exams are over; all the students are out and free and have time on their hands. Summer weather is perfect for a march. The summit takes place in the heart of Toronto: everybody in Canada has a friend in Toronto where they can stay during a protest.

And can we not say that assembling the greatest number of police in one spot in the history of Canada, and spending more on fences and security than Canada has ever spent before, has a provocative effect?

Why didn’t they keep both summits in Huntsville? Or, as several people have pointed out, at a remote Canadian Forces base where air transport and physical security are already in place?

Update: Jonathan Kay thinks the media and the echo chamber of Twitter, Facebook, blogs, and instant messaging combine to make a few incidents appear far bigger and more scary than they really are:

This is one of those stories the social media has gotten wrong: a million tweeters all tweeting up the same three burning police cruisers and few dozen wrecked storefronts. The number of protestors wasn’t even that big (even if the media insists on calling the protests “massive.”) The estimate I’ve seen thrown around is about 10,000. To put that figure in perspective, the number of protestors who swarmed Quebec City at the Summit of the Americas in 2001 was approximately 100,000 — tens times as large.

[. . .]

As I approached the intersection of Queen and Spadina, I could see a rowdy crowd of several thousand gathered. There were a few earnest placards in evidence (“Mother earth convenes the G-6billion. Fuck the G20″). But mostly, it was just excited-looking teenagers surrounding the cop car, like hyenas around their kill. In that moment, it looked like things were about to get truly ugly. I began eying the stores lining Queen, trying to predict which one would get trashed first.

But then came the sirens, and the atmosphere changed very quickly. From down Queen Street, headed eastbound, a speeding convoy of unmarked white busses stopped outside the Silver Snail comic store, and out poured police in full riot gear — helmets, batons, body armor. From an accompanying black suburban came a few even more serious-looking fellows, including at least one with a military-style assault rifle. They never said a word, never issued a threat, never fired any of their crowd-control weapons. They just advanced, in a line, several officers deep, toward the heart of Spadina and Queen. There wasn’t any violence — at least none that I saw. The worst I witnessed was a single protestor who threw a bottle from amidst the anonymity of the crowd, which gained a few oohs and ahs after it fell harmlessly on the concrete.

June 26, 2010

The smell of burning police cars

Just when you think the anarchists have decided to let the government look like fools, they pull stuff like this, allowing the security forces to justify the billion+ they’ve spent on the G8/G20 summit meetings:

Pic from Eric Squair.

Pic from Pete Forde. The second police car in this photo also gets the warm treatment from the anarchists.

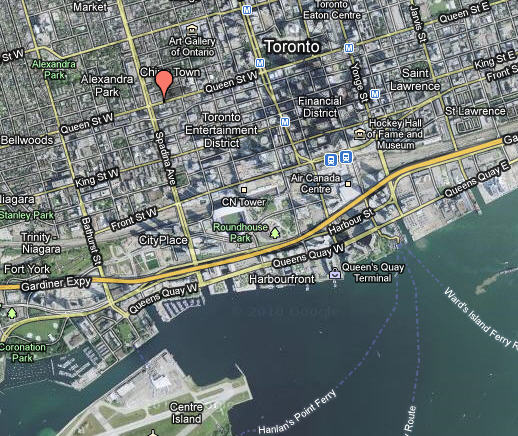

For those not familiar with Toronto, this is approximately here:

Update: Michael Coren has a suggestion to get the police more involved in deterring the rioters:

An idea. Tell the cops that these anarchist criminals are actually confused, gentle Polish visitors trying to find help at an airport. Not only will deadly force ensue but the police will lie about it all after the fact.

Update, the second: Another burning police car, further east at (I assume) Queen King St. and Bay St.

Pic by Marissa Nelson.

Update, the third: In spite of all the images available of burning or burnt-out police vehicles, the three above were the only ones. Rarely have so many twittered so much about so few . . .

G20 arrests not considered “major enough” to release details

Siri Agrell notes the inconsistency of Toronto police over the (32 at time of writing) arrests made around the G20 area:

When asked for details of the arrest of a deaf man at Friday night’s demonstration, Burrows [of the Integrated Security Unit] said he had neither a name or the charges.

“Very rarely do we ever release information unless it’s a major arrest, major charges, big investigation or something like that,” he said. “That’s our standard practice. This guy was arrested last night, there’s nothing major about it. we’d never put a release out about that.”

And yet, the police regularly release information about minor incidents, ranging from lost property to suspicious behaviour. Surely, the arrest of Toronto citizens exercising their right to protest during a major international event warrents some transparency?

Yet another example of the police taking advantage of the situation to expand their practical reach?

So teenagers sending sext messages, a lost urn and some guy trying to pick up Toronto women are worthy of police updates, but details of arrests made during the G20, when police have been given huge powers, aren’t worth releasing?

In a nutshell, yes.