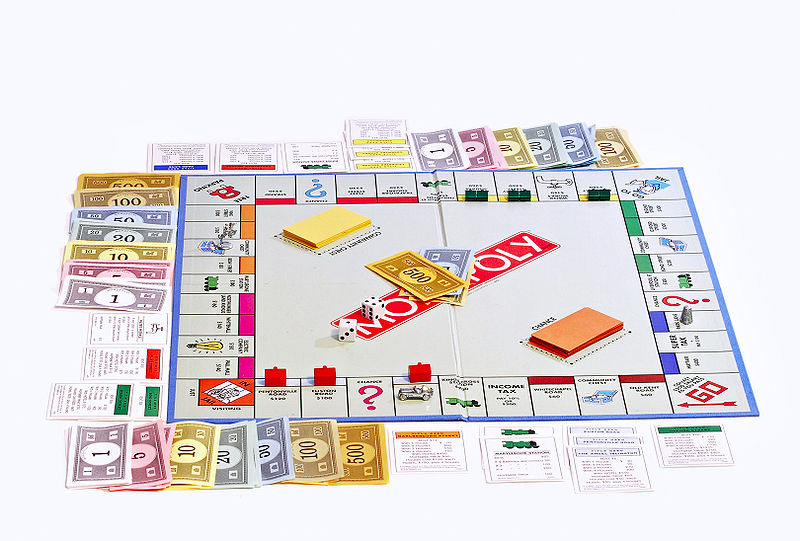

There are many railfans who still believe, strongly and passionately, that General Motors was involved in a devious plot to kill off the streetcars across North America in order to sell more buses. At Vox.com, Joseph Stromberg explains that this wasn’t the case — in fact, the killer of the streetcar/interurban/radial railway systems was their willingness to lock in to long-term uneconomic agreements with local governments in exchange for monopoly privileges:

Back in the 1920s, most American city-dwellers took public transportation to work every day.

There were 17,000 miles of streetcar lines across the country, running through virtually every major American city. That included cities we don’t think of as hubs for mass transit today: Atlanta, Raleigh, and Los Angeles.

Nowadays, by contrast, just 5 percent or so of workers commute via public transit, and they’re disproportionately clustered in a handful of dense cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago. Just a handful of cities still have extensive streetcar systems — and several others are now spending millions trying to build new, smaller ones.

So whatever happened to all those streetcars?

“There’s this widespread conspiracy theory that the streetcars were bought up by a company National City Lines, which was effectively controlled by GM, so that they could be torn up and converted into bus lines,” says Peter Norton, a historian at the University of Virginia and author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City.

But that’s not actually the full story, he says. “By the time National City Lines was buying up these streetcar companies, they were already in bankruptcy.”

Surprisingly, though, streetcars didn’t solely go bankrupt because people chose cars over rail. The real reasons for the streetcar’s demise are much less nefarious than a GM-driven conspiracy — they include gridlock and city rules that kept fares artificially low — but they’re fascinating in their own right, and if you’re a transit fan, they’re even more frustrating.

This is one of the reasons I’m generally against new plans to re-introduce streetcars (or their modern incarnations generally grouped under the term “light rail”), because they fail to address one of the key reasons that the old street railway/interurban/radial systems died: they were sharing road space with private vehicles. Light rail can provide a useful urban transportation option if they have their own right-of-way, but not if they are merely adding to the gridlock of already overcrowded city streets.

And once again, I’m not anti-rail … I founded a railway historical society and I commute most work days on a heavy rail commuter network. I don’t hold this position due to some anti-rail animus. If anything, I regret the passing of railway systems more than most people do, but I recognize that they have to be self-supporting (or close to self-supporting) to have a chance to survive. Being both more expensive and less convenient than alternative transportation options is a sure-fire path to extinction.