Sigmund Freud was a perverted old cokehead, but he had some useful insights. One of them is that anxiety works like a spring (my paraphrase). You need a spring to have a certain tension in order to work, but if you compress it too tightly, it breaks. Anxiety that can’t be discharged (his term) in healthy, socially beneficial ways instead gets discharged in unhealthy, neurotic ways.

That’s what happened with Anna O., history’s most famous psychiatric patient. She had a very turbulent love/hate relationship with her father, as tightly wound girls do. When he became deathly ill on a family vacation, the unresolvable tension caused a whole host of physical symptoms, including hysterical paralysis. Pioneering psychologist Josef Breuer “talked her through” it, finally resolving the emotional conflict and “curing” the patient.

All this would’ve been interesting, but largely irrelevant, were it not for World War I. The world at large didn’t care about the problems of overprivileged Jewish girls, but they did care about their soldiers suddenly going crazy in the trenches. Once military doctors finally ruled out a physical cause, they were left with Freudian explanations: A soldier can’t stop fighting, because he’s an honorable, dutiful soldier. Yet that soldier must stop fighting. The only honorable way out is a wound. If the enemy doesn’t wound him, then, his subconscious will. Hence the bizarre “conversion disorders” — hysterical blindness, paralysis, mutism, etc. — characteristic of “shell shock.”

But a funny thing happened. While everyone now acknowledged the real power of the subconscious mind, we sort of … forgot … about it. Psychology, particularly psychotherapy, went back to being a ghetto Jewish preoccupation. Bored, over-privileged housewives might go to a shrink to talk through their “issues”, but as for the rest of us, well, if we weren’t going into combat anytime soon, why bother? Outside of a few crusty old reactionaries (like yours truly) making fun of SJWs, when was the last time you heard the word “neurotic”?

But that’s the thing: either the subconscious is real, or it isn’t. When we say “neurotic” (the few of us who still do), we usually mean people like Anna O. — rich, cosseted, politically active human toothaches who try to force the entire world into the all-encompassing drama of their Daddy Issues (see also: Virginia Woolf). But that’s not how Freud meant it. According to him, we’re all neurotic to some degree or another, because that’s just how anxiety works.

We all have strong emotional impulses that run counter our self-image. Hence the entire panoply of pop-Freudianism: The preacher who constantly rails against homosexuality from the pulpit is secretly gay (“projection”). The strict, controlling, everything-in-its-place type is a sadist (“anal-retentive”). The player who can’t settle down with any woman is actually trying to find a Mommy figure (“Oedipus complex”). And, of course, the — ahem — daddy of them all, the crippling Daddy Issues that make feminists such fun.

But that’s just the thing: Either anxiety works that way or it doesn’t. Just because we don’t see a specific syndrome in ourselves doesn’t mean we don’t have a whole bunch of anxiety we need to discharge. Just because it’s subclinical, in other words, doesn’t mean it’s not real, or unimportant. See for example the legions of keyboard commandos who show up in the comments of any blog with more than fourteen readers. Yeah, sure, it’s possible that those guys all got kicked out of SEAL Team 6 for being too badass … but it’s probably classic identification. They’re deeply uneasy about the world and their place in it, so they construct themselves an identity as the Rambo of Evergreen Terrace.

Severian, “High Anxiety”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-03-16.

February 27, 2023

QotD: Sigmund Freud’s insights

February 19, 2023

February 15, 2023

QotD: The divine right of kings

The best case for divine right monarchy is the voters’ behavior in a democracy. Unfortunately, the worst case for divine right monarchy is: divine right monarchs.

England’s James I, for instance, was a deeply weird dude. Though he wrote a whole book about his divine right to rule, he kept his weirdness sufficiently in check so as not to alienate his court. Alas, his heir didn’t bother, and we know how that turned out. And so it went with just about any divine right monarch — the more people who actually saw him, the flimsier the theory seemed. History is full of examples of kingdoms “ruled” by insane kings, but not too many of kingdoms thriving when the people knew the king was a lunatic. Feebleminded monarchs are generally kept under lock and key by their courtiers, or they end up Epsteined.

Even democracies once understood this. Pick any 19th century American legislator, for example. As P.J. O’Rourke once said about rock stars, to call one of these guys a drunken, borderline-illiterate pervert just means you’ve read his autobiography. But they knew enough to keep it sufficiently in check around the voters, so that so long as they didn’t actually Chappaquiddick someone, they’d face no repercussions.

Speaking of Chappaquiddick, the Media has always been complicit in the great game of Fool-the-Rubes. They only do it for Democrats now, of course, but that’s the real problem these days: the Media has been doing all this for so long, and so successfully, that they no longer feel the need to bother. Just as Charles I decided to let his freak flag fly because hey, why not, I’m the king, so the Democrat-Media complex went all-in in 2008. You watch these guys — Don Lemon, say, mocking Trump voters as illiterate hicks — and the expression on their face is one of relief. It feels good to finally let it all out, and the more you do it, the better it feels.

Severian, “Rule by Lunatic”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-01-29.

January 30, 2023

Crime on Toronto’s public transit system is merely a symptom of a wider social problem

As posted the other day, Matt Gurney’s dispiriting experiences on an ordinary ride on the TTC are perhaps leading indicators of much wider issues in all of western society:

“Toronto subway new train” by BeyondDC is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 .

Caveats abound. Toronto is, relatively speaking, still a safe city. The TTC moves many millions of people a week; a large percentage of whom are not being knifed, shot or burnt alive. And so on. We at The Line also suspect that whatever is happening in Toronto isn’t happening only in Toronto, but Toronto’s scale (and the huge scope of the TTC specifically) might be gathering in one place a series of incidents that would be reported as unconnected random crimes in any other city. A few muggings in Montreal or Winnipeg above the usual baseline for such crimes won’t fit the media’s love of patterns as much as a similar number of incidents on a streetcar or subway line.

Fair enough, duly noted, and all that jazz.

But what is happening out there?

Your Line editors have theories, and we’ve never hesitated to share them before: we think the pandemic has driven a portion of the population bonkers. We’d go further and say that we think it has left all of us, every last one, less stable, less patient, less calm and less empathetic. For the vast majority of us, this will manifest itself in many unpleasant but ultimately harmless ways. We’ll be more short-tempered. Less jovial at a party. Less patient with strangers, or even with loved ones. Maybe a bit more reclusive.

But what about the relatively small majority of us that were, pre-2020, already on the edge of deeper, more serious problems? What about those who were already experiencing mental-health issues, or living on the edge of real, grinding poverty?

It’s not like the overall societal situation has really improved, right? COVID-19 itself killed tens of thousands, and took a physical toll on many more, but we all suffered the stress and fear not just of the plague, but of the steps taken to mitigate it. (Lockdowns may have been necessary early in the pandemic, but they were never fun or easy, and that societal bill may be coming due.) Since COVID began to abate, rather than a chance to chill out, we’ve had convoys, a war, renewed plausible risk of nuclear war, and now a punishing period of inflation and interest-rate hikes that are putting many into real financial distress. We are coping with all of this while still processing our COVID-era stress and anxiety.

The timing isn’t great, is what we’re saying.

And on the other side of the coin, basically all our societal institutions that we’d turn to to cope with these issues — hospitals, social services, homeless shelters, police forces, private charities, even personal or family support networks — are fried. Just maxed out. We have financial, supply chain and, most critically, human-resource deficits everywhere. The people we have left on the job are exhausted and at their wits’ end.

This leaves us, on balance, less able to handle challenges than we were in 2020, due to literal exhaustion of both institutions and individuals. Meanwhile, against the backdrop of this erosion of our capacity, our challenges have all gotten worse!

It’s not hard to do the mental math on this, friends. It seems to us that in 2020, the policy of Canadian governments from coast to coast to coast, and at every level, was to basically keep a lid on problems like crime, homelessness, housing prices and shortages, mental health and health-care system dysfunction, and probably others we could add. One politician might put a bit more emphasis on some of these issues than others, in line with their partisan priors, but overall, the pre-2020 status quo in Canada was pretty good, and our political class, writ large, basically self-identified as guardians of that status quo, while maybe tinkering a bit at the margins (and declaring themselves progressive heroes for the trouble of the tinkering).

But then COVID-19 happens, and all our problems get worse. And all our ways of dealing with those problems get less effective. It doesn’t have to be by much. Just enough to bend all those flatlined (or maybe slightly improving) trendlines down. Instead of homelessness being kind of frozen in place in the big cities, it starts getting worse, bit at a time, month after month. The mental-health-care and homeless shelter systems that weren’t really doing a great job in 2020, but were more or less keeping big crises at a manageable level, started seeing a few more people fall through the cracks each month, month after month. Those people are just gone, baby, gone.

The health-care system that used to function well enough to keep people reasonably content, if not happy, locks up, and waitlists balloon, and soon we can’t even get kids needed surgeries on time.

The housing shortage goes insane, and prices somehow survive the pandemic basically untouched.

The court system locks up, meaning more and more violent criminals get bail and then re-offend, even killing cops when they should be behind bars.

None of these swings were dramatic. They were all just enough to set us on a course to this, a moment in time where the problems have had years to compound themselves and are now compounding each other.

Here’s the rub, folks. The Line doesn’t believe or accept that any of the problems we face today, alone or in combination, are automatically fatal. We can fix them all. But we need leaders, including both elected officials and bureaucrats, who fundamentally see themselves as problem fixers, and who understand right down deep in their bones that that is what their jobs are, and that they are no longer what they’ve been able to be for generations: hands-off middle managers of stable prosperity.

January 27, 2023

Post-pandemic travelling on the TTC: ride the Red Rocket … cautiously

Matt Gurney posted a series of tweets about his recent subway experiences in Toronto:

I rode the TTC three times today. Once to downtown from my home in midtown. Once within downtown to a different place. And then home from downtown.

On two of those three rides, there was someone having a very obvious mental-health crisis on the vehicle with us.

The first one was a young man who clapped his hands over his ears and shrieked incoherently at random intervals. And then he got off.

The second, an older man sat in a chair and screamed nonsense constantly for ten stops. Maybe more. That’s just when I got off.

I’m working on a bigger piece for later so I’ll save any complex thoughts and big conclusions for then. But there was something interesting I noticed today. I’m a regular TTC rider. Not daily but frequent. And for the first time today, I’m noticing gallows humour and planning.

“Good luck to everyone,” cracked one guy. There was laughter. Everyone knew what he meant.

But I’m also seeing little groups of strangers agreeing to each keep watch on one direction or another. Sometimes also joking about it.

None of this is funny, but my gut tells me that if Torotonians are now so thoroughly convinced that riding the TTC is so risky that it’s worth a dark joke, any politician who reacts to the next unprovoked attack or murder with a proposal for a national summit is gonna get smoked.

I like the TTC. I have great access to it. It’s super convenient and affordable. It’s a huge asset for me. I have token cufflinks. I’m a fan, is what I’m saying.

I’m now at the point where I’d think twice before taking my kids on it. And we used to ride it just to kill the time.

My son used to stand on the couch in our living room looking out the window counting buses as they went by, loudly shouting to announce each one. Getting to go on a bus or subway or a streetcar was an event for him. My daughter, maybe a bit less excited. Still loved it.

Ah man.

Anyway. I hope tomorrow is better.

Update: You might think the increased concern over using the TTC might be merely a bit of confirmation bias informed by recent reporting, but apparently the situation is serious enough that Toronto Police will be stepping up their presence on the system.

December 31, 2022

If Hell is “other people”, then the deepest level of Hell must be “other high school students”

Tom Knighton on a recent post from FEE about the awfulness of the school experience for a lot of students:

“Leaside High School entrance Toronto Ontario Canada” by ammiiirrrr is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 .

I was never a big fan of school. While I always thought education was important, I never liked school itself.

Part of that was because I was the kid most likely to get picked on, but even when that wasn’t happening, I still didn’t like it. Learning boring stuff while not getting to delve deeper into interesting topics just made it a chore to be endured.

Couple with the fact that cruelty is such a part of the “educational experience”, it’s no wonder that I didn’t like it.

Hell, even when everyone was being chill, the fact that I didn’t fit in did a number on me, including a time when I genuinely wanted to end my own life. I don’t talk about that kind of thing much, but it was a stark reality of that time.

[…]

Granted, I always chalked my difficulties at the time — and I’m much better now, I should note — with a number of things besides the structure of school itself. Mostly the fact that it was a small school, I was the weird kid, and while I had friends, I never felt like I really fit in.

Yet I can’t rule out that the structured nature of education at the time contributed greatly to the problem.

As noted in the original piece, the patterns for suicidal behavior in teens don’t match up with adults. That tells us that there’s something at play other than just the weather, the temperature, or whatever.

Regardless, it raises serious questions about our schools as an environment. Teachers and administrators would tell you that they strive to create a nurturing environment for students of all ages. I’m pretty sure most of them mean it, too.

Yet these studies suggest that they’re failing. Miserably.

But let’s not ignore the possibility that much of this may well be because, frankly, kids can be little sociopaths. They’re mean. They’re cruel. Someone will seek out those they perceive as weak and victimize them while others get to enjoy the show, even while being glad they’re not the target.

Then there’s the fact that it’s impossible to hide from any deficiencies you might have, including social deficiencies just as good fortune with finding romantic partners of your preferred sex and that’s going to play a role as well.

December 21, 2022

QotD: The Spoon Theory

The blogger Christine Miserandino, who has lupus, coined the term spoonie in a 2003 post called “The Spoon Theory”. A spoon, Miserandino explained, equates to a certain amount of energy. The Healthy have unlimited spoons. The Sick — the spoonies — only have a few. They might use one spoon to shower, two to get groceries, and four to go to work. They have to be strategic about how they spend their spoons.

Since then, the theory has ballooned into an illness kingdom filled with micro-celebrities offering discounts on supplements and tinctures; podcasts on dating as a spoonie; spoonie clubs on college campuses; a weekly magazine; and online stores with spoonie merch. In the past few years, spoonie-ism has dovetailed with the #MeToo movement and the ascendance of identity politics. The result is a worldview that is highly skeptical of so-called male-dominated power structures, and that insists on trusting the lived experience of individuals — especially those from groups that have historically been disbelieved. So what do spoonies need from you? “To believe; Be understanding; Be patient; To educate yourself; Show compassion; Don’t question”.

Spoonie illnesses include, but are not limited to, serious diseases like multiple sclerosis and Crohn’s disease, but also harder-to-diagnose ones that manifest differently in different people: polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), endometriosis, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, dysautonomia, Guillain-Barré Syndrome, gastroparesis, and fibromyalgia. Another spoonie illness is myalgic encephalomyelitis — or chronic fatigue syndrome — which has now been linked to long Covid.

These illnesses are often “invisible”: To most people, spoonies may appear healthy and able-bodied, especially when they’re young. Many of the conditions affect women more frequently, and most are chronic illnesses that can be managed, but not cured. A diagnosis often lasts for a lifetime, while symptoms come, go, morph, and multiply.

Spoonies find community in having complicated conditions that are often hard to identify and difficult to treat. That’s why a lot of spoonies include a zebra emoji in their social media bios, borrowed from the old doctor’s adage: “When you hear hoof beats, look for horses, not zebras.” In other words: assume your patient has a more common illness, rather than a rare one.

The spoonie mantra might be: I am the zebra.

Although the term is relatively new, the spoonies fit into a long history of women having amorphous, hard-to-diagnose conditions. Since ancient times, women who were diagnosed under the general category of “hysteria” were prescribed treatments such as sex, hanging upside down, and the placement of leeches on the abdomen. Then, in the 19th century, the new field of psychoanalysis concluded that women with hysteria were not suffering from physical disorders, but mental ones. Whether the women’s inexplicable pain was a function of their brains or of their bodies — or of each other (see mass hysteria), or of the devil (see Salem, 1692) — has always been a fraught subject.

And then the internet arrived and created a 21st century version of Freud’s Vienna, in which everyone was always on the couch, perpetually the patient.

Suzy Weiss, “Hurts So Good”, Common Sense, 2022-09-06.

December 18, 2022

November 26, 2022

QotD: The search for “authenticity”

The search for authenticity is not only futile but actively harmful, both psychologically and socially, for in general, authenticity is thought to require behavior without the restraints of normal civilized conduct, amongst which are the capacity and willingness on occasion to be hypocritical and insincere. Of course, the precise amount of hypocrisy and insincerity that one should indulge in is always a matter of judgment, but authenticity is brutish if it means saying and doing whatever one wants whenever one wants it.

Shakespeare knew that authenticity, in this sense, is for most people impossible and in all cases undesirable. The first few lines of Sonnet 138 should be enough to prove it:

When my love swears that she is made of truth,

I do believe her, though I know she lies,

That she may think me some untutored youth,

Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.

Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young,

Although she knows my days are past the best,

Simply I credit her false speaking tongue:

On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed.Should Shakespeare abandon his love because he knows she is inauthentic in what she says? Of course not:

Oh, love’s best habit is in seeming trust …

Away, then, with your self-esteem, your true self and your authenticity, and all the bogus desiderata of modern psychology.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Lose Yourself”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-11-10.

November 13, 2022

QotD: Your “true self”

When someone above the age of young adulthood says that he is searching for himself, it is almost always because he has been behaving badly or has had reversals in life. No one goes off in search of himself whose life is satisfactory. The assumption is that, once found, the true self will be charming, successful, and, above all, good. This is because man is born good, though — paradoxically — everywhere is bad. Finding yourself is a panacea, and you will live happily ever after.

Unfortunately, the search for the true self has a tendency to go on for years or even for decades. I used to ask my patients who said that they were in search of themselves how they would know when they had found it. The true self, after all, is not like a mislaid pair of cuff links. They said that their unhappiness would fall away when they found it, presumably like the outer mold of a casting. But they had no real idea of what a better life than the one they were leading would be like. Mostly they thought of the better life as one of luxury and more consumption, bathing in ass’ milk rather than in mere water. When I suggested that they needed to lose rather than to find themselves, they asked how one lost oneself.

“By being interested in something outside of and other than oneself,” I said.

“How do you do that?” I asked.

Here the weakness of my advice became apparent to me. I have been interested in many different things in my life, usually in succession, and my library is a testimony to my tendency to serial monomania; but I have never been interested in nothing, and therefore have no idea how people develop the capacity to be interested in something (that is to say, in anything) ex nihilo, so to speak, nor do I have any recollection of how I did so myself. I suspect (though I cannot prove) that modern education, which lays emphasis on the relevance of what is taught to children’s present lives rather than, as it should be, on its irrelevance, is partly to blame for the very large numbers of people who cannot lose themselves, and therefore are left to the vagaries of entertainment provided for them under our current regime of bread and circuses. The unassuageable thirst for entertainment is both a manifestation and a symptom of a profound boredom with the world. Indeed, entertainment is also one of the greatest causes of boredom in the world, inasmuch as everyday reality can now rarely compete in raw sensation with entertainment. But since dealing with everyday reality remains a necessity for most people, it results in boredom because it is compared with entertainment. Only a deeper engagement with the world can avoid or overcome this problem.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Lose Yourself”, Taki’s Magazine, 2018-11-10.

October 6, 2022

The pendulum swings back toward institutionalization

During the 1950s and 60s, many mental institutions were shut down due to concerns about the way the patients in those institutions were being treated. Those suffering from mental health issues were, to a large degree, just discharged into the larger community with few supports to help them re-integrate. Today, the concerns about severely mentally ill peoples’ actions may be pushing the system back toward some form of formal re-institutionalization, as Michael Shellenberger reports for Common Sense:

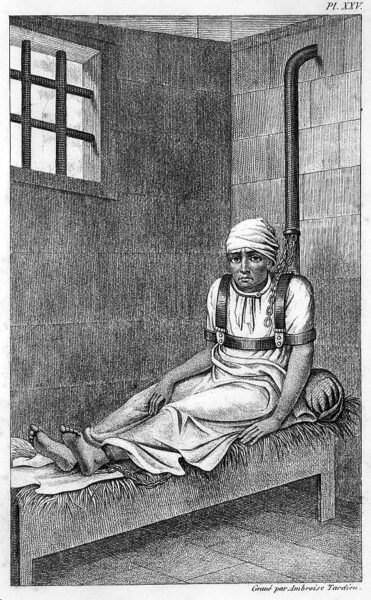

William Norris, shackled sitting upright on his bed at Bedlam, 1838.

Engraving by Ambroise Tardieu, Des maladies mentales Esquirol via Wikimedia Commons.

Though it is difficult to get an exact estimate, a large body of research makes clear that people like Zisopoulos, Mesa, and Simon are just three among hundreds of cases of people in New York alone — to say nothing of cities like Los Angeles, Seattle, San Francisco and others — in which mentally ill people off their medication have assaulted or killed people. And if you think the problem is getting worse, you are right.

In 2021, felony assaults in New York’s subway were almost 25 percent higher compared to 2019, despite a lower ridership because of the pandemic. The number of people pushed onto tracks rose from 9 in 2017 to 20 in 2019 to 30 in 2021. Psychiatrists and emergency department workers in San Francisco and Los Angeles tell me that they have seen a significant increase in homeless patients in psychotic states over the last few years.

How have we arrived at the point where we leave people with psychosis to their demons, and leave the public to take their chances? How have we allowed so many of our cities to have no decent plans or places for the burgeoning number of the violent mentally ill on the streets?

There are two major forces at work. The first is that the U.S. never created a functioning mental health care system. The second is that powerful groups have effectively prevented dangerously mentally ill people from getting treatment.

Starting in the late 19th century, the U.S. created large psychiatric hospitals, often in the countryside, known as asylums, for the mentally ill. Asylums were a major progressive achievement because they delivered, for many decades, significantly more humane, evidence-based care to people who, until then, had often been neglected, abused, or even killed.

But by the middle of the 20th century, the reputation of psychiatric hospitals was in tatters — and deservedly so. Conditions in many of them were appalling, even barbaric. People who were not severely mentally ill were sometimes subjected to years of involuntary hospitalization.

Many reformers just wanted better funding and oversight, but other reformers were more radical, and proposed shutting the hospitals down entirely and replacing them with community-based clinics. Some reformers claimed that serious mental illnesses were the result of poverty and inequality, not biology, and argued that they could be cured through radical social change.

The reformers largely won. State hospitals were shut down in droves before sufficient community centers could be built to treat the suffering. Over the next two decades, as state mental hospitals emptied out, many released patients ended up on the street, or incarcerated. Those community clinics that did start operating tended to treat “the worried well” — those suffering from comparatively low-level anxiety and depression, rather than psychosis.

Decades later, governments were still cutting funding for the treatment of the mentally ill. New York State in 2010 reduced Medicaid reimbursement for inpatient stays of the mentally ill in hospitals beyond 12 days. As a result, New York hospitals released the mentally ill earlier than they should have. From 2012 to 2019, the number of mentally ill adults in inpatient psychiatric care in hospitals and mental institutions in New York City declined from 4,100 to just 3,000. Meanwhile, the number of seriously mentally ill homeless people rose from 11,500 to 13,200.

The story is similar in California. Between 2012 and 2019, more than one-third of the group homes in San Francisco that served mentally ill and disabled people under the age of sixty closed their doors. Why? The measly Medi-Cal and Medicare reimbursement of $1,058 per person per month, and rising estate prices, made it more valuable for the private owners of group homes to sell than to keep operating them.

At the national level, the same dynamic was in play. The U.S. as a whole lost 15,000 board and care beds for the mentally ill and disabled between 2010 and 2016. Today, approximately 121,000 mentally ill people are conservatively estimated to be living on America’s streets.

September 28, 2022

September 11, 2022

QotD: De-institutionalization

[In Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness, Andrew] Scull stresses the degree to which external pressures have shaped psychiatry. “Community psychiatry” supplanted “institutional psychiatry” in part because of professional insecurity. Psychiatrists needed a new model for dealing with mental diseases to keep pace with the advances that mainstream health care was making with other diseases. Fiscal conservatives viewed the practice of confining hundreds of thousands of Americans to long-term commitment as overly expensive, and civil libertarians viewed it as unjust.

Deinstitutionalization began slowly at first, in the 1950s, but the pace accelerated around 1970, despite signs that all was not going according to plan. On the ground, psychiatrists noticed earlier than anyone else that the most obvious question — where are these people going to go when they leave the mental institutions? — had no clear answers. Whatever misgivings psychiatrists voiced over the system’s abandonment of the mentally ill to streets, slums, and jails was too little and too late.

That modern psychiatry is mostly practiced outside of mental institutions is not its only difference from premodern psychiatry. Scull devotes extensive coverage to two equally decisive developments: the rise and fall of Freudianism, and psychopharmacology.

The Freudians normalized therapy in America and provided crucial intellectual support for the idea that mental health care is for everyone, not just the deranged. Around the same time as deinstitutionalization, Freud’s reputation, especially in elite circles, was on a level with Newton and Copernicus. Since then, Freudianism has mostly gone the way of phlogiston and leeches. That happened not just because people decided the psychoanalysts’ approach to therapy didn’t work but also because insurance wouldn’t pay for it. Insurance would, however, pay for modes of therapy that were less open-ended than the “reconstruction of personality that psychoanalysis proclaimed as its mission”, more targeted to a specific psychological symptom, and, most crucially of all, performed by non-M.D.s. Therapy was on the rise, but psychiatrists found themselves doing less and less of it.

As psychiatry cast aside Freudian concepts such as the “refrigerator mother”, which rooted mental illness in psychodynamic tensions, it increasingly trained its focus on biology. Drugs contributed to, and gained a boost from, this reorientation. Scull loathes the drug industry and only grudgingly allows that it has made improvements in the lives of mentally ill Americans. He divides up the vast American drug-taking public into three groups: those for whom they work, those for whom they don’t work, and those for whom they may work, but not enough to counter the unpleasant side effects. He argues that the last two groups are insupportably large.

Stephen Eide, “Soul Doctors”, City Journal, 2022-05-18.

August 31, 2022

QotD: John Keegan’s The Face of Battle

The Face of Battle (1976) is in some ways an oddly titled book. The title implies there is a singular face to battle that the author, John Keegan, is going to discover (and indeed, to take his forward, that is certainly the question he looked to answer). But that plan doesn’t survive contact with the table of contents, which makes it quite clear that Keegan is going to present not one face of battle, but the faces of three different battles and they will look rather different. Rather than reinventing the wheel, I am going to follow Keegan’s examples to make my point here (although I should note that of course The Face of Battle is a book not without its flaws, as is true with any work of history).

Keegan’s first battle is Agincourt (1415). While famous for the place of the English longbow in it, at Agincourt the French advance (both mounted and dismounted) did reach the English lines; of this the sources for the battle are quite clear. And so the terror we are discussing is the terror of shock; not shock in the sense of a sudden shock or in the sense of a jolt of electricity, rather shock as the opposite of fire. Shock combat is the combat when two bodies of soldiers press into each other in mass hand-to-hand combat (which is, contrary to Hollywood, not so much a disorganized melee as a series of combats along the line of contact where the two formations meet). The advancing French had to will themselves forward into a terrifying shock encounter, while the English had to (like our hoplites above) hold themselves in place while watching the terrifying prospect of a shock engagement walk steadily towards them.

There is actually quite a bit of evidence that the terror of a shock engagement is something different from the other terrors of war (to be clear, not “better” or “worse”, merely different in important ways). There are numerous examples of units which could stand for extend periods under fire but which collapsed almost immediately at the potential of a shock engagement. To draw a much more recent example, at Bai Beche in 2001, a force of Taliban withstood two days of heavy bombing and had repulsed an infantry assault besides, but collapsed almost immediately when successfully surprised by a cavalry charge (yes, in 2001) in their rear (an incident noted in S. Biddle, “Afghanistan and the Future of Warfare”, Foreign Affairs 82.2 (2003)).

And so our sources for state-on-state pre-gunpowder warfare (which is where you tend to find more fully “shock” oriented combat systems) stress similar sequences of fear: the dread inspired by the sight of the enemy army drawing up before you (Greek literature is particularly replete with descriptions of teeth-chattering and trembling in those moments and it is not hard to imagine why), followed by the steady dread-anticipation as the armies advanced, each step bringing that moment of collision closer. Often in such engagements one side might break before contact as the fear not of what was happening, but what was about to happen built up. And only then the long anticipated not-so-sudden shock of the formations coming together – rarely for long given the overpowering human urge not to be near an enemy trying to stab you with a sharp stick. There is something, I think, quite fundamental in the human psyche that understands another human with a sharp point, or a huge horse rapidly closing on a deeper level than it understands bullets or arrows.

Which brings us to Keegan’s second battle, Waterloo (1815), defined in part by the ability of the British to manage to hold firm under extended fire from artillery and infantry. The French artillery in an 80-gun grand battery opened fire at 11:50am and kept it up for hours until the French cavalry advanced (hoping that the British troops were suitably “softened” by the guns to be dislodged) at 4pm. In contrast to Agincourt (or a hoplite battle) which may have ended in just a couple of hours and consisted mostly of grim anticipation, soldiers (on both sides) at Waterloo were forced to experience a rather different sort of terror: forced to stand in active harm for hours on end, as bullets and cannon shot whizzed overhead.

The difference of this is perhaps most clearly extreme if we move still forward to the Somme (1916) and bombardment. The British had prepared for their assault with a week long artillery barrage, in which British guns fired 1.5 million shells (that is about 148 shells fired a minute, every minute for a week). At the first sound of guns, soldiers (in this case, the Germans, but it had been the French’s turn just that February to be on the receiving end of a bombardment at Verdun) rushed into their dug-out bomb shelters at the base of their trench and then waited. Unlike the British at Waterloo, who might content themselves that, one way or another, the terror of fire would not last a day, the soldier of WWI had no way of knowing when the barrage would cease and the battle proper begin. Indeed, they could not see the battlefield at all, only sit under the ground as it shook around them and try to be ready, at any moment when the barrage stopped to rush back up to the lip of the trench to set up the machine guns – because if they were late to do it, they’d arrive to find British grenades and bayonets instead.

We will get into wounds, both physical and mental, next week, but it is striking to me that repeatedly there are reports after such barrages of soldiers so mentally broken by the strain of it that they wandered as if dazed or mindless, apparently driven mad by the bombardment. Reports of such immediate combat trauma are vanishingly rare in the pre-modern corpus (Hdt. 6.117 being the rare example). And it is not hard to see why the constant threat of sudden, unavoidable death hanging over you, day and night, for days or in some cases weeks on end produces a wholly different kind of terror.

And yet, to extend beyond Keegan’s three studies, in talking to contemporary veterans, it seems to me this terror of fire – being forced to stand (or hide) under long continuous fire – is not always quite the same as the terror of the modern battlefield. Of course I can only speak to this second hand (but what else can a historian generally do?), but there seems to be something different about a battlefield where everything might seem peaceful and fine and even a bit boring until suddenly the mortar siren sounds or a roadside IED goes off and the peril is immediate. The experience of such fear sometimes expresses itself in a sort of hypervigilance which seems entirely unknown to Greek or Roman writers (who in most cases could hardly have needed such vigilance; true surprise attacks were quite rare as it is extremely hard to sneak one entire army up on another) and doesn’t seem particularly prominent in the descriptions of “shell-shock” (which today we’d call PTSD) from the First World War, compared to the prominence of intense fatigue, the thousand-yard-stare and raw emotional exhaustion. I do wonder though if we might find something quite analogous looking into the trauma of having a village raided by surprise under the first system of war.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part IIa: The Many Faces of Battle”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

July 29, 2022

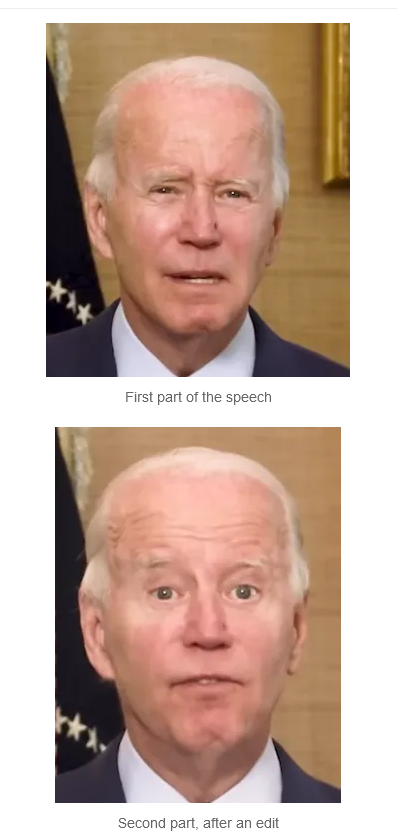

Joe “Leonid Brezhnev” Biden

Chris Bray says if you saw anyone else speaking the way Joe Biden did the other day, you’d be concerned about medical or psychological crises:

This is an increasingly strange moment, and the President of the United States is an increasingly strange and incoherent man. This is not something that has to be a partisan point, and I propose no next step that serves anyone’s politics — just notice, for now, and figure out the rest on your own terms. I’ve compared Joe Biden to Leonid Brezhnev, and Biden’s place in our political trajectory to Brezhnev’s position as an indicator of societal decline, and here we are again. I’ll get to the insane substance in a moment, but let’s start with the obviousness of the man’s bizarre affect. Turn off your politics for a moment and pretend you’re just watching the old guy who lives down the street. Watch this closely, ideally on full screen — and notice that he blinks once, around the 1:22 mark (and maybe a little one at 0:07):

If you saw a pastor or a small-town mayor or a school principal speaking like this, you would think it was unsettling. If you saw an elderly man in your family speaking this way, you’d call the doctor. This is video posted on the blue-checked POTUS account, official footage that someone at the White House decided to move to the foreground, and it’s disturbing. They didn’t notice the dead-eyed, overdosed stare?

The effect of the whole speech this footage is taken from is even more disturbing, if you can stomach it all. At least watch from 8:20 to 8:30, if you’re inclined to take notice of the thing, and watch the weird shift.