The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 8 Nov 2024In March 1950, Stalin finally approves Kim Il-sung’s plans for an invasion of South Korea. But why now? Today Indy looks at the wider Cold War context that fed into Stalin and Mao Zedong’s decision making. He also examines whether the lack of a clear and public commitment from the US to defend the Asian theatre helped to invite the invasion.

(more…)

November 9, 2024

Did US Indecision Encourage Stalin in Korea?

October 9, 2024

The Korean War 016 – South Koreans Invade the North! – October 8, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 8 Oct 2024This week the KPA continue to grapple with the hole made by the landings at Incheon, as South Korean forces push past the 38th Parallel. MacArthur’s attention, however, is already on his next big gambit: a landing at Wonsan. South Korean forces may very well beat him to the punch, though, as their drive north continues. Beyond the Yalu River, Mao Zedong watches these developments closely, and plans his response.

Chapters

00:51 Recap

01:12 Seoul Aftermath

03:50 ROK Enters North Korea

05:28 The UN Resolution

07:36 Crossing the Parallel

14:25 The Wonsan Plan

16:38 Conclusion

(more…)

October 5, 2024

Did South Korea Provoke the Korean War?

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 4 Oct 2024Was South Korea on the verge of invading North Korea in 1949? Today Indy looks at the bloody fighting across the Korean border in the years leading up to war. Then he asks the question, why did Kim finally decide to invade South Korea in the early months of 1950?

(more…)

September 21, 2024

The Dramatic Birth of Two Korean States

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 20 Sep 2024The United Nations plan is to reunite the divided Korean peninsula into a single state. But soon the USA and USSR have installed their own leaders, neither of whom are willing to compromise. By the end of 1948 Kim Il-Sung and Syngman Rhee stand at the head of separate North and South Korean states.

(more…)

September 18, 2024

The Korean War 013 – 70,000 UN Troops Head for Incheon – September 17, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 17 Sep 2024[NR: For some unknown reason, YT decided to restrict the original release of this video, so I’m replacing it with the “Censored” version posted a couple of days later.]

This week sees the UN forces execute Operation Chromite, the amphibious invasion of the port of Incheon, far behind enemy lines. There are many hurdles to clear before this can happen, including the physical one of one of the world’s largest tidal ranges, which leaves many kilometers of mud flats in the approaches. There is also a UN counterattack at the same time, designed to perhaps break out of the Pusan Perimeter, or at least tie down big chunks of the enemy in the south.

(more…)

September 7, 2024

A Nation Divided, Part One

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 6 Sep 2024Join us as we unfold the post-WW2 history of Korea that resulted in political escalation and eventually a military conflict in 1950. Stay tuned for the remaining parts of this mini-series!

(more…)

August 21, 2024

The Korean War Week 009 – Bloody UN Victory at Naktong Bulge – August 20, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 20 Aug 2024The Marines are deployed to back up the UN forces facing disaster in the Naktong Bulge and by the end of the week the tide has turned, and the crack North Korean 4th Division has been shattered. There is also fighting around the whole rest of the Pusan Perimeter, and it is shrinking from all the attacks, though on the east coast the battle goes in favor of the South Korean forces this week at Pohang-Dong.

(more…)

August 14, 2024

The Korean War Week 008 – The First UN Counterattack – August 13, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 13 Aug 2024The first UN large scale counterattack goes off this week; this by the American Task Force Kean. It has both successes and failures, and it runs right into a new North Korean offensive. The fighting happens just about everywhere on the Pusan Perimeter this week, though. That’s the area into which the UN forces have been compressed, and it is particularly threatening at the Naktong Bulge. It is, plain and simple, a week of desperate and bloody fighting and that’s about it.

Chapters

00:47 Recap

01:27 The Pusan Perimeter

04:31 Task Force Kean

07:44 The Naktong Bulge

10:09 The Fight Around Daegu

13:45 Summary

(more…)

July 10, 2024

The Korean War – Never Fear, MacArthur’s Here! – Week 003 – July 9, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 9 Jul 2024American troops have arrived in Korea and engage the KPA — the forces of the North — in the field this week for the first time. It does not go well for them. In fact, it’s hard to imagine it going worse. The Americans are outnumbered and outgunned and are routed. In fact, the KPA are advancing all over the country, though they are taking heavy casualties themselves.

(more…)

July 3, 2024

The Korean War Week 002 – The Fall of Seoul – July 2, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 2 Jul 2024The North Korean forces are advancing all over, and this week they take Seoul, the South’s capital city, after just a few days of the war. There is another tragedy for the South when the Han River Bridge is blown while thousands of people are crossing it, resulting in hundreds of civilian deaths. The world responds to the invasion — condemning it everywhere, and the Americans decide to send in ground forces to help the South.

(more…)

June 26, 2024

The Korean War Begins – Week 1 – June 25, 1950

The Korean War by Indy Neidell

Published 25 Jun 2024Despite the fact that there have been clear signs that they might soon invade South Korea, when the North actually does in force on June 25th, 1950, it comes as a complete shock to the world. But is this a full invasion, or just cross border raids such as there were in 1949? And is there something more behind this? Stalin’s Soviets? Mao’s Chinese? And how will the world react? Find out this week as our week by week coverage of the war begins!

(more…)

December 6, 2022

The coming of the Korean War

In Quillette, Niranjan Shankar outlines the world situation that led to the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950:

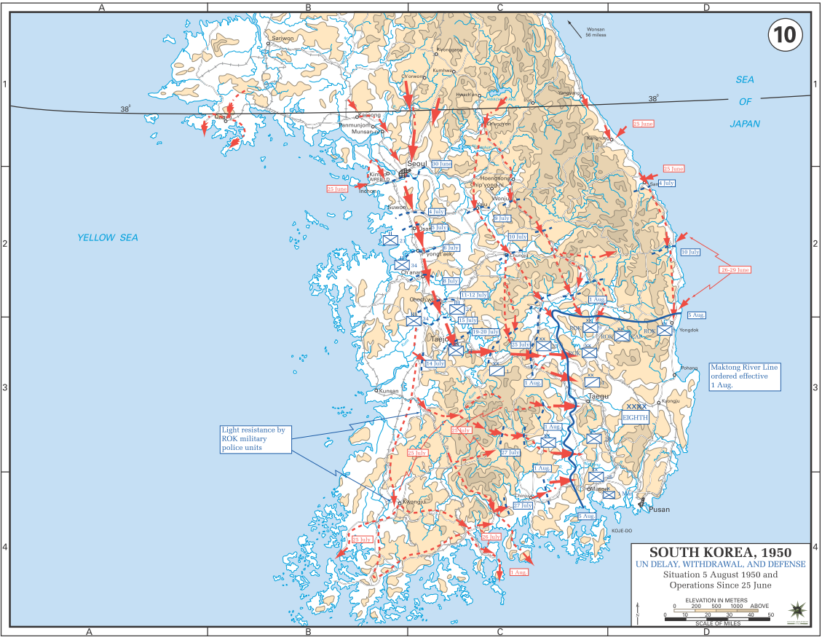

Initial phase of the Korean War, 25 June through 5 August, 1950.

Map from the West Point Military Atlas — https://www.westpoint.edu/academics/academic-departments/history/korean-war

The Korean War was among the deadliest of the Cold War’s battlegrounds. Yet despite yielding millions of civilian deaths, over 40,000 US casualties, and destruction that left scars which persist on the peninsula today, the conflict has never received the attention (aside from being featured in the sitcom M*A*S*H) devoted to World War II, Vietnam, and other 20th-century clashes.

But like other neglected Cold War front-lines, the “Forgotten War” has fallen victim to several politicized and one-sided “anti-imperialist” narratives that focus almost exclusively on the atrocities of the United States and its allies. The most recent example of this tendency was a Jacobin column by James Greig, who omits the brutal conduct of North Korean and Chinese forces, misrepresents the underlying cause of the war, justifies North Korea’s belligerence as an “anti-colonial” enterprise, and even praises the regime’s “revolutionary” initiatives. Greig’s article was preceded by several others, which also framed the war as an instance of US imperialism and North Korea’s anti-Americanism as a rational response to Washington’s prosecution of the war. Left-wing foreign-policy thinker Daniel Bessner also alluded to the Korean War as one of many “American-led fiascos” in his essay for Harper’s magazine earlier this summer. Even (somewhat) more balanced assessments of the war, such as those by Owen Miller, tend to overemphasize American and South Korean transgressions, and don’t do justice to the long-term consequences of Washington’s decision to send troops to the peninsula in the summer of 1950. By giving short shrift to — or simply failing to mention — the communist powers’ leading role in instigating the conflict, and the violence and suffering they unleashed throughout it, these depictions of the Korean tragedy distort its legacy and do a disservice to the millions who suffered, and continue to suffer, under the North Korean regime.

Determining “who started” a military confrontation, especially an “internal” conflict that became entangled in great-power politics, can be a herculean task. Nevertheless, post-revisionist scholarship (such as John Lewis Gaddis’s The Cold War: A New History) that draws upon Soviet archives declassified in 1991 has made it clear that the communist leaders, principally Joseph Stalin and North Korean leader Kim Il-Sung, were primarily to blame for the outbreak of the war.

After Korea, a Japanese imperial holding, was jointly occupied by the United States and the Soviet Union in 1945, Washington and Moscow agreed to divide the peninsula at the 38th parallel. In the North, the Soviets worked with the Korean communist and former Red Army officer Kim Il-Sung to form a provisional “People’s Committee”, while the Americans turned to the well-known Korean nationalist and independence activist Syngman Rhee to establish a military government in the South. Neither the US nor the USSR intended the division to be permanent, and until 1947, both experimented with proposals for a united Korean government under an international trusteeship. But Kim and Rhee’s mutual rejection of any plan that didn’t leave the entire peninsula under their control hindered these efforts. When Rhee declared the Republic of Korea (ROK) in 1948, and Kim declared the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) later that year, the division was cemented. Each nation threatened to invade the other and began preparing to do so.

What initially prevented a full-scale attack by either side was Washington’s and Moscow’s refusal to provide their respective partners with support for the military reunification of the peninsula. Both superpowers had withdrawn their troops by 1949 to avoid being dragged into an unnecessary war, and the Americans deliberately withheld weapons from the ROK that could be used to launch an invasion.

However, Stalin began to have other ideas. Emboldened by Mao Zedong’s victory in the Chinese Civil War and frustrated by strategic setbacks in Europe, the Soviet premier saw an opportunity to open a “second-front” for communist expansion in East Asia with Beijing’s help. Convinced that Washington was unlikely to respond, Stalin gave Kim Il-Sung his long-sought “green-light” to reunify the Korean peninsula under communist rule in April 1950, provided that Mao agreed to support the operation. After Mao convinced his advisers (despite some initial difficulty) of the need to back their Korean counterparts, Red Army military advisers began working extensively with the Korean People’s Army (KPA) to prepare for an attack on the South. When Kim’s forces invaded on June 25th, 1950, the US and the international community were caught completely off-guard.

Commentators like Greig, who contest the communists’ culpability in starting the war, often rely on the work of revisionist historian Bruce Cumings, who highlights the perpetual state of conflict between the two Korean states before 1950. It is certainly true that there were several border skirmishes over the 38th parallel after the Soviet and American occupation governments were established in 1945. But this in no way absolves Kim and his foreign patrons for their role in unleashing an all-out assault on the South. Firstly, despite Rhee’s threats and aggressive posturing, the North clearly had the upper hand militarily, and was much better positioned than the South to launch an invasion. Whereas Washington stripped Rhee’s forces of much of their offensive capabilities, Moscow was more than happy to arm its Korean partners with heavy tanks, artillery, and aircraft. Many KPA soldiers also had prior military experience from fighting alongside the Chinese communists during the Chinese Civil War.

Moreover, as scholar William Stueck eloquently maintains, the “civil” aspect of the Korean War fails to obviate the conflict’s underlying international dimensions. Of course, Rhee’s and Kim’s stubborn desire to see the country fully “liberated” thwarted numerous efforts to establish a unified Korean government, and played a role in prolonging the war after it started. It is unlikely that Stalin would have agreed to support Pyongyang’s campaign to reunify Korea had it not been for Kim’s persistent requests and repeated assurances that the war would be won quickly. Nevertheless, the extensive economic and military assistance provided to the North Koreans by the Soviets and Chinese (the latter of which later entered the war directly), the subsequent expansion of Sino-Soviet cooperation, the Stalinist nature of the regime in Pyongyang, Kim’s role in both the CCP and the Red Army, and the close relationship between the Chinese and Korean communists all strongly suggest that without the blessing of his ideological inspirators and military supporters, Kim could not have embarked on his crusade to “liberate” the South.

Likewise, Rhee’s education in the US and desire to emulate the American capitalist model in Korea were important international components of the conflict. More to the point, all the participants saw the war as a confrontation between communism and its opponents worldwide, which led to the intensification of the Cold War in other theaters as well. The broader, global context of the buildup to the war, along with the UN’s authorization for military action, legitimized America’s intervention as a struggle against international communist expansionism, rather than an unwelcome intrusion into a civil dispute among Koreans.

September 29, 2019

Being a dictator is a stressful vocation

Gustav Jönsson reviews a new book by Professor Frank Dikötter on twentieth-century dictators:

One of the first things to emerge from Professor Frank Dikötter’s eagerly awaited new book How to Be a Dictator is that it is a stressful vocation: there are rivals to assassinate, dissidents to silence, kickbacks to collect, and revolutions to suppress. Quite hard work. Even the most preeminent ones usually meet ignominious ends. Mussolini: summarily shot and strung upside down over a cheering crowd. Hitler: suicide and incineration. Ceausescu: executed outside a toilet block. Or consider the fate of Ethiopia’s Haile Selassie: rumoured to have been murdered on orders of his successor Mengistu Haile Mariam, he was buried underneath the latter’s office desk. Not the most alluring career trajectory, one might say.

Dikötter’s monograph is a study of twentieth century personality cults. He examines eight such cults: those created by Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Kim Il-sung, Duvalier, Ceausescu, and Mengistu. For them, cultism was not mere narcissism, it was what sustained their regimes; foregoing cultism, Dikötter argues, caused swift collapse. Consider Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Cambodians were unsure of Pol Pot’s exact identity for years, even after he had assumed leadership of the country. The Khmer Rouge, meanwhile, was in its initial stages merely called “Angkar” — “The Organisation.” There was no inspiring iconography. There was no ritualised leader worship. There was only dark terror. Dikötter quotes historian Henri Locard: “Failing to induce adulation and submissiveness, the Angkar could only generate hatred.” The Khmer Rouge soon lost its grip on the country. Dikötter makes an obligatory reference: “Even Big Brother, in George Orwell’s 1984, had a face that stared out at people from every street corner.”

Readers of Orwell will remember that INGSOC has no state ideology. There is only what the Party says, which can change from hour to hour. Likewise, Dikötter argues, there was no ideological core to twentieth century dictatorships; there was only the whim of the dictator. Nazism, for example, was not a coherent creed. It contained antisemitism, nationalism, neo-paganism, etc., but its essence was captured in one of its slogans: The Führer is Always Right. That is what the creed amounted to. Indeed, the NSDAP referred to itself simply as “the Hitler movement.” Nazism was synonymous with Hitlerism. Italian Fascism was perhaps even more vacuous. The regime’s slogan was simple: Mussolini is Always Right. Explaining his method of politics, Mussolini said: “We do not believe in dogmatic programmes, in rigid schemes that should contain and defy the changing, uncertain, and complex reality.”

While it is uncontroversial to argue that Nazism and Fascism were without ideology, as Dikötter writes, the “issue is more complicated with communist regimes.” Naturally, Marxism was connected with Stalin, Mao, Ceausescu, Kim, and Mengistu. But Dikötter rightly says that it was Lenin’s revolutionary vanguard, not Marx’s philosophical works, that inspired them. Doctrines can be interpreted in contradictory ways, creating schismatic movements — as shown throughout the history of socialism. In this regard personality cults are far safer because they are substantively empty. Marxist dictators thus subverted Marxism. Engels had said that socialism in one country was impossible, but that is what Stalin’s Soviet Union favoured. Or consider Kim’s North Korea, which in 1972 replaced Marxism with Great Leader Thought. And as Dikötter writes, “Mao read Marx, but turned him on his head by making peasants rather than workers the spearhead of the revolution.” Reading Marx under Marxism, Dikötter says, was highly imprudent: “One was a Stalinist under Stalin, a Maoist under Mao, a Kimist under Kim.” In short, Marxism was whatever the dictator said, and not what Marx had actually written.