My old friend George Jonas, now forcibly confined within the Mount Pleasant Cemetery, observed of the times:

In the not too distant past, people who were illiterate could neither read nor write. These days they can, with disastrous results for the culture.

He quoted his own old friend Stephen Vizinczey:

No amount of learning can cure stupidity, and formal education positively fortifies it.

David Warren, “On paper logic”, Essays in Idleness, 2020-02-22.

February 3, 2025

QotD: Illiteracy then and illiteracy now

January 17, 2025

“… most of them can do simple low-IQ jobs like manual labor, basic retail, or writing for the New York Times“

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander discusses the highly controversial national IQ estimates of Richard Lynn … I’m sure I don’t need to spell out exactly why they were (and continue to be) controversial:

Lynn’s national IQ estimates (source)

Richard Lynn was a scientist who infamously tried to estimate the average IQ of every country. Typical of his results is this paper, which ranged from 60 (Malawi) to 108 (Singapore).

People obviously objected to this, and Lynn spent his life embroiled in controversy, with activists constantly trying to get him canceled/fired and his papers retracted/condemned. His opponents pointed out both his personal racist opinions/activities and his somewhat opportunistic methodology. Nobody does high-quality IQ tests on the entire population of Malawi; to get his numbers, Lynn would often find some IQ-ish test given to some unrepresentative sample of some group related to Malawians and try his best to extrapolate from there. How well this worked remains hotly debated; the latest volley is Aporia‘s Are Richard Lynn’s National IQ Estimates Flawed? (they say no).

I’ve followed the technical/methodological debate for a while, but I think the strongest emotions here come from two deeper worries people have about the data:

First, isn’t it horribly racist to say that people in sub-Saharan African countries have IQs that would qualify as an intellectual disability anywhere else?

Second, isn’t it preposterous and against common sense to compare sub-Saharan Africans to the intellectually disabled? You can talk to a Malawian person, and talk to a person with Down’s Syndrome, and the former is obviously much brighter and more functional than the latter. Doesn’t that mean that the estimates have to be wrong?

But both of these have simple answers, which IMHO defuse the worrying nature of Lynn’s results. These answers aren’t original to me, but as far as I know, nobody has put them together in one place before. Going over each in turn:

1: Isn’t It Super-Racist To Say That People In Sub-Saharan African Countries Have IQs Equivalent To Intellectually Disabled People?

No. In fact, it would be super-racist not to say this! We shouldn’t conflate advocacy with science. But if we did, Lynn’s position would make better anti-racist advocacy than his detractors’.

The “racist” position is that all IQ differences between groups are genetic. The “anti-racist” position is that they’re a product of environment — things like nutrition, health care, and education.

We know that in the US, where we do give people good IQ tests, whites average IQ 100 and blacks average IQ 85.

If IQ was 100% genetic, we should expect Africans to have an IQ of 85, since American and African blacks have similar genes. This isn’t exactly right — US blacks have some intermixing with whites, and only some of Africa’s staggering diversity reached the US — but it’s close enough.

May 31, 2024

“You only support that because it’s in your self-interest to do so”

Helen Dale considers the painful notion that political ideas that work for the “elite” (defined in various ways) may not work at all for people unlike members of any given “elite”:

When I reviewed Rob Henderson’s Troubled for Law & Liberty at Liberty Fund, I made this observation:

The reality that classical liberalism — the closest to my own political views, I admit — has at least a whiff of the luxury belief around it stings. It’s discomforting to acknowledge that what goes by the name of paternalism has its own intellectual pedigree, while liberalism can be a system developed by the clever, for the clever. “Highly educated and affluent people are more economically conservative and socially liberal,” Henderson says. “This doesn’t make sense. The position is roughly that people shouldn’t have to adhere to norms and if/when they inevitably hurt themselves or others, then there should be no safety net available. It’s a luxury belief.”

[…]

Joseph Heath […] uses the phrase “self-control aristocracy” to describe those who really do benefit from maximal freedom. These are people who can make better choices for themselves than any authority could make on their behalf. When the state or large corporates boss them (us) around, they (we) get really bloody annoyed. They (we) know better!

Heath’s phrase is simply a layman’s term for the personality trait various formal tests measure, and which overlaps with executive function to a considerable but as yet unknown degree.

Because I am self-conscious about my membership in the self-control aristocracy, I am acutely aware of the fact that, when I think about questions of “individual liberty” in society, I come to it with a particular set of class interests. That is because I stand to benefit much more from an expansion of the space of individual liberty than the average person does – because I have greater self-control. So I recognize that, while a 24-hour beer store would be great for me, it would be a mixed blessing for others […]

What does this have to do with libertarianism? It is important because every academic proponent of libertarianism – understood loosely, as any doctrine that assigns individual liberty priority over other political values – is a member of the self-control aristocracy. As a result, they are advancing a political ideal that benefits themselves to a much greater extent than it benefits other people. In most cases, however, they do so naively, because they do not recognize themselves as members of an elite, socially-dominant group, that stands to benefit disproportionately. They think of liberty as something that creates an equal benefit for all.

My response to reading Professor Heath’s piece was simplicity itself: I feel seen. I’ve even done the night school thing while working full-time. I’ve written books and chosen to play sports that require a long time and lots of skill to master. I retired at 45.

Politically, I’m not a libertarian. Libertarianism is a distinctive and largely American ideology (as the recent and bonkers fracas at its US Convention indicates) with philosophically unusual deontological roots. I am, however, within the British and French tradition of classical liberalism (which does assign individual liberty priority over other political values). And like many classical liberals I’ve been blind to problems of laws and governance for people unlike me.

I disclose this because I’ve worked in policy development in both devolved and national parliaments. I’ve probably given politicians and civil servants alike dud advice. There is almost certainly a shit policy out there (in either Scotland or Australia) with my name on it. However, this mind-blindness doesn’t only apply to people who advocate libertarian politics. I think it applies to a significant number of political ideologies just as strongly as it does to libertarianism.

That is, the ideology serves the inherited personality traits of those who promote it. “You only support that because it’s in your self-interest to do so” always struck me as a genuinely mean criticism of people who were involved in politics and policy (I may have been one of those people, natch). The problem — as I’ve been forced to accept — is that it’s true.

July 31, 2023

2023 compared with the world of C.M. Kornbluth’s “Marching Morons”

John C. Wright on what he calls our “incompetocracy”:

The conceit of the C.M. Kornbluth story “The Marching Morons” (Galaxy, April 1951) is that low-IQ people, having less practical ability to plan for the future, will reproduce more recklessly hence in greater numbers than high-IQ people, leading to a catastrophic general decline in intelligence over the generations.

A small group of elite thinkers tries, by any means necessary, to maintain a crumbling world civilization being overrun by an ever increasing underclass of morons.

In this morbid and unhappy little short story, the solution to overpopulation was the Final Solution, that is, mass murder of undesirables followed by the murder of the architect of the solution.

The eugenic genocide is played for laughs, as the morons are herded aboard death-ships, told they are going on vacation to Venus. The government forges postcards to their widows and orphans to maintain the fraud, which the morons are too stupid to penetrate.

You may recognize a similar conceit from the film Idiocracy (2006), written and directed by Mike Judge. Unlike the short story, no solution is proposed for the overpopulation of undesirables.

No one seems to note the absurd self-flattery involved in entertaining Malthusian eugenicist fears: no one regards himself as a moron unworthy of reproduction. Margaret Sanger did not volunteer to sterilize herself on the grounds that she was a moral cripple suffering from Progressive mental illness, hence unfit.

It is only the working man, the factory hand, the field hand, who is unfit, and usually he is an immigrant from some Catholic hence illiterate nation, with a fertile wife and a happy home.

The happy Catholic with his ten children will not die alone, empty and unloved, in some sterile euthanasia center in Canada, like the Progressive will, and so the Progressive hates the happy father like Gollum hates the sun.

The self-flattery is absurd because, first, IQ is not genetic — if it were, average IQ scores for a given bloodline would not change over two generations. Darwinism allows for genetic changes only over geologic eras.

Second, education in the modern day is inversely proportional to intelligence. No intelligent man would or does subject himself to the insolent falsehoods of college indoctrination: we are too independent in thought to be allowed to pass.

Third, a truly intelligent man, if he thought his bloodline was in danger of being outnumbered and swamped, rather than trying to inflict infertility on the competition, would seek the only intelligent solution compatible with honesty and decency: lifelong monogamy in a culture that forbids contraception and encourages maternity. He would, indeed, become Catholic, and attempt to evangelize his neighbors likewise.

A truly intelligent man would accept rather than reject the divine injunction to be fruitful and multiply. The idea of overpopulation is and always was a Progressive scare tactic, meant to undermine and control the underclass. It is the tactic of making the poor feel poorly for trying to use resources and grow rich. It is the politics of enforced poverty.

Why else would billionaires on private jets fly to Davos to eat steak dinners over wine, in order to pressure peons to ride bikes and eat bugs?

Our salvation is that they cannot even do that right. These James Bond style villains who are committing slow genocides with experimental injections, with wars against farming, against guns, against police, against oil drilling, against nuclear energy, and against family life, have not sacrificed the billions their dark and ancient gods crave dead, but this is due only to their lack of skill and organization.

September 12, 2020

Andrew Sullivan on a “genetic case for communism”

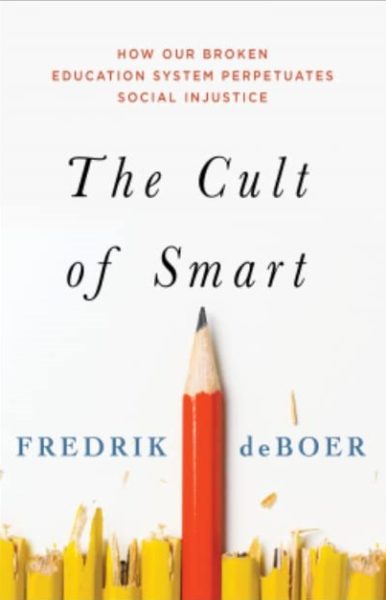

Actually, this isn’t the case Sullivan himself is making, but he’s summarizing a recent book by Fredrik deBoer, The Cult of Smart: How our broken education system perpetuates social injustice:

There aren’t many books out there these days by revolutionary communists who are into the genetics of intelligence. But then there aren’t many writers like Freddie DeBoer. He’s an insistently quirky thinker who has managed to resist the snark, cynicism and moral preening of so many others in his generation — and write from his often-broken heart. And the core of his new book, The Cult of Smart, is a moral case for those with less natural intelligence than others — the ultimate losers in our democratic meritocracy, a system both the mainstream right and left have defended for decades now, and that, DeBoer argues, gives short shrift to far too many.

This isn’t a merely abstract question for him. He has grappled with it directly. As a school teacher he encountered the simple, unavoidable fact that some humans are more academically gifted than others, and there’s nothing much anyone can do about it. He recalls his effort to teach long division to a boy who had managed to come a long way socially (he’d gone from being a hell-raiser to a good student) but who still struggled with something as elemental as long division: “At one point he broke into tears, as he had several times before … I exhaled slowly and felt myself give up, though of course I would never tell him so. I tried to console him, once again, and he said, ‘I just can’t do it.’ And it struck me, with unusual force, that he was right.”

What DeBoer tries to do is explain how our current culture and political system is geared to torment, distress and punish this kid for no fault of his own. “This is the cult of smart,” DeBoer proclaims. “It is the notion that academic value is the only value, and intelligence the only true measure of human worth. It is pernicious, it is cruel, and it must change.” It has become un-American — or perhaps it always was? — to say that an individual has natural limits, that, even with extremely hard work, he won’t always be able to realize his dreams. And this is not because of anything he has done or failed to do — but simply because of his draw in the genetic lottery of life. The very American cult of education is supposed to end this injustice — except that it doesn’t, because it can’t, and its brutal logic actually exposes and entrenches the least defensible inequality of all, the inequality of nature.

This genetic reality — in fact, the very idea of nature existing at all — is currently a taboo topic on the left. In the most ludicrously untrue and yet suffocatingly omnipresent orthodoxy of our time, critical theory leftists insist that everything on earth is entirely socially constructed, that all inequality is a function of “oppressive systems”, and that human nature itself is what John Locke called a “white paper, void of all characters” — the famous blank slate. Freddie begs to differ: “Human behavioral traits, such as IQ, are profoundly shaped by genetic parentage, and this genetic influence plays a larger role in determining human outcomes than the family and home environment.”

People are not just born unequally and unfairly into class, and culture, and place, they are inherently unequal in various ways in their very nature: “not everyone has the same ability to do calculus; not everyone has the same grasp of grammar and mechanics … we can continue to beat our heads against the wall, trying to force an equality that just won’t come. Or we can face facts and start to grapple with a world where everyone simply can’t be made equal.” And this is not a counsel of despair. What Freddie is arguing is that, far from treating genetic inequality as a taboo, the left should actually lean into it to argue for a more radical re-ordering of society. They shouldn’t ignore genetics, or treat it as unmentionable, or go into paroxysms of fear and alarm over “eugenics” whenever the subject comes up. They should accept that inequality is natural, and construct a politics radical enough to counter it.

[…]

This genetic case for communism can leave a reader a little disoriented, I have to say, if only for its novelty. But it is more coherent, it seems to me, than a leftism that assumes that genes are irrelevant to humans and society, that the ultimate goal is to be as smart and thereby wealthy as possible, and that we can set up an educational system where everyone, regardless of their genetic inheritance, can succeed or fail by their own efforts. What sounds like a meritocratic dream is, in practice, a brutal and unforgiving formula for most who can’t achieve it — and has obviously failed if its task is to foster equality. In fact, mass education appears to have increased the gulf between rich and poor. As Freddie notes, “education is not a weapon against inequality; it is an engine of inequality.”

June 28, 2019

QotD: “Intelligence” is just a noun

Howard Gardner has also convinced us that the word intelligence carries with it undue affect and political baggage. It is still a useful word, but we shall subsequently employ the more neutral term cognitive ability as often as possible to refer to the concept that we have hitherto called intelligence, just as we will use IQ as a generic synonym for intelligence test score. Since cognitive ability is an uneuphonious phrase, we lapse often so as to make the text readable. But at least we hope that it will help you think of intelligence as just a noun, not an accolade.

We have said that we will be drawing most heavily on data from the classical tradition. That implies that we also accept certain conclusions undergirding that tradition. To draw the strands of our perspective together and to set the stage for the rest of the book, let us set them down explicitly. Here are six conclusions regarding tests of cognitive ability, drawn from the classical tradition, that are by now beyond significant technical dispute:

- There is such a thing as a general factor of cognitive ability on which human beings differ.

- All standardized tests of academic aptitude or achievement measure this general factor to some degree, but IQ tests expressly designed for that purpose measure it most accurately.

- IQ scores match, to a first degree, whatever it is that people mean when they use the word intelligent or smart in ordinary language.

- IQ scores are stable, although not perfectly so, over much of a person’s life.

- Properly administered IQ tests are not demonstrably biased against social, economic, ethnic, or racial groups.

- Cognitive ability is substantially heritable, apparently no less than 40 percent and no more than 80 percent.

Charles Murray, “The Bell Curve Explained”, American Enterprise Institute, 2017-05-20.

June 15, 2019

The real explanation for our lack of moonbases/Concorde 2’s/great walls/pyramids

Homoitalicus Blog responds to a new book [At Our Wit’s End by Edward Dutton and Michael Woodley of Menie] that concludes that we (western civilization) are headed toward a similar fate as the western Roman Empire:

The reason that these staggering feats of engineering haven’t been repeated is more to do with economics and politics than with any perceived lack of engineering Genius in the population. The authors fail to reflect that emerging from the massively centralised wartime economy of the West there was an enormous technological infrastructure of scientists and capable administrators just sat there with no more Nazis to fight, communist megalomaniacs to support, Atom bombs to build and test, or greatest seabourne invasions in history to plan and implement.

This was probably the greatest concentration of intellect ever harnessed to a single cause and hopefully we’ll never need to see its like again

With the war done and dusted some new purpose needed to be found for all this talent, the way of government being what it is, returning all these geniuses to normal boring peacetime activity was never an option.

Newly nationalised aircraft industries took the wartime inventions of jet engine and the rest and evolved them with massive amounts of financial input from the government into Concorde, truly a magnificent aircraft but one which could uncharitably be described as using taxpayers’ money to ferry plutocrats from one side of the Atlantic to the other. Whether it ever really paid for itself is a moot point and the unseemly haste with which it was dumped after the crash tends to imply that its 50-year-old airframes were becoming a burden, and the economic case for making a new generation of supersonic planes is weak – luckily the will in the west for another taxpayer-funded effort doesn’t seem to be there. That is progress.

Likewise the man on the moon, possible only because of the Cold War space race.

The authors might as well explain the fact that we haven’t build another pyramid of Giza or Great Wall of China.

Their assertion that a general decline in the amount of creativity (which is correlated strongly with g) is justified by the observable decline in the quality of the output of the BBC. However other possible reasons for this are the infestation of Cultural Marxism and its baleful handmaid, Political Correctness, which really mitigate against creative thought. It is impossible to imagine making The Life of Brian, or The Sweeney or countless other shows which we enjoyed in our youth nowadays largely for reasons of PC and the fact that the BBC’s mission is now brainwashing rather than entertainment. State broadcasters the world over will suffer from the same problem, as does (worryingly) the world of academe in which speakers of truth or opinion which lie outwith accepted and very tightly bounded acceptability, are routinely no-platformed or summarily sacked. The teaching of history and the humanities generally has been debased, and only the STEM subjects seem to have resisted (excluding the question of Climate Change which has taken on the trappings of a religion rather than serious science).

As a consequence it is impossible to separate the effects of CM from the mooted results of a generalised decline in intelligence, and the authors are wrong not to point this out.

They don’t consider either the likely effect of the 20th century’s great blood letting in the fields of Flanders. A substantial proportion of the best and brightest of a generation were ground into the mud there before being able to procreate. I would be surprised if that had no effect on the quality of the gene pool.

H/T to the Continental Telegraph for the link.

May 30, 2017

QotD: The uses of IQ

Suppose that the question at issue regards individuals: “Given two 11 year olds, one with an IQ of 110 and one with an IQ of 90, what can you tell us about the differences between those two children?” The answer must be phrased very tentatively. On many important topics, the answer must be, “We can tell you nothing with any confidence.” It is well worth a guidance counselor’s time to know what these individual scores are, but only in combination with a variety of other information about the child’s personality, talents, and background. The individual’s IQ score all by itself is a useful tool but a limited one.

Suppose instead that the question at issue is: “Given two sixth-grade classes, one for which the average IQ is 110 and the other for which it is 90, what can you tell us about the difference between those two classes and their average prospects for the future?” Now there is a great deal to be said, and it can be said with considerable confidence — not about any one person in either class but about average outcomes that are important to the school, educational policy in general, and society writ large. The data accumulated under the classical tradition are extremely rich in this regard, as will become evident in subsequent chapters.

[…]

We agree emphatically with Howard Gardner, however, that the concept of intelligence has taken on a much higher place in the pantheon of human virtues than it deserves. One of the most insidious but also widespread errors regarding IQ, especially among people who have high IQs, is the assumption that another person’s intelligence can be inferred from casual interactions. Many people conclude that if they see someone who is sensitive, humorous, and talks fluently, the person must surely have an above-average IQ.

This identification of IQ with attractive human qualities in general is unfortunate and wrong. Statistically, there is often a modest correlation with such qualities. But modest correlations are of little use in sizing up other individuals one by one. For example, a person can have a terrific sense of humor without giving you a clue about where he is within thirty points on the IQ scale. Or a plumber with a measured IQ of 100 — only an average IQ — can know a great deal about the functioning of plumbing systems. He may be able to diagnose problems, discuss them articulately, make shrewd decisions about how to fix them, and, while he is working, make some pithy remarks about the president’s recent speech.

At the same time, high intelligence has earmarks that correspond to a first approximation to the commonly understood meaning of smart. In our experience, people do not use smart to mean (necessarily) that a person is prudent or knowledgeable but rather to refer to qualities of mental quickness and complexity that do in fact show up in high test scores. To return to our examples: Many witty people do not have unusually high test scores, but someone who regularly tosses off impromptu complex puns probably does (which does not necessarily mean that such puns are very funny, we hasten to add). If the plumber runs into a problem he has never seen before and diagnoses its source through inferences from what he does know, he probably has an IQ of more than 100 after all. In this, language tends to reflect real differences: In everyday language, people who are called very smart tend to have high IQs.

All of this is another way of making a point so important that we will italicize it now and repeat elsewhere: Measures of intelligence have reliable statistical relationships with important social phenomena, but they are a limited tool for deciding what to make of any given individual. Repeat it we must, for one of the problems of writing about intelligence is how to remind readers often enough how little an IQ score tells about whether the human being next to you is someone whom you will admire or cherish. This thing we know as IQ is important but not a synonym for human excellence.

Charles Murray, “The Bell Curve Explained”, American Enterprise Institute, 2017-05-20.

October 29, 2016

QotD: IQ and different types of intelligence

My last IQ-ish test was my SATs in high school. I got a perfect score in Verbal, and a good-but-not-great score in Math.

And in high school English, I got A++s in all my classes, Principal’s Gold Medals, 100%s on tests, first prize in various state-wide essay contests, etc. In Math, I just barely by the skin of my teeth scraped together a pass in Calculus with a C-.

Every time I won some kind of prize in English my parents would praise me and say I was good and should feel good. My teachers would hold me up as an example and say other kids should try to be more like me. Meanwhile, when I would bring home a report card with a C- in math, my parents would have concerned faces and tell me they were disappointed and I wasn’t living up to my potential and I needed to work harder et cetera.

And I don’t know which part bothered me more.

Every time I was held up as an example in English class, I wanted to crawl under a rock and die. I didn’t do it! I didn’t study at all, half the time I did the homework in the car on the way to school, those essays for the statewide competition were thrown together on a lark without a trace of real effort. To praise me for any of it seemed and still seems utterly unjust.

On the other hand, to this day I believe I deserve a fricking statue for getting a C- in Calculus I. It should be in the center of the schoolyard, and have a plaque saying something like “Scott Alexander, who by making a herculean effort managed to pass Calculus I, even though they kept throwing random things after the little curly S sign and pretending it made sense.”

And without some notion of innate ability, I don’t know what to do with this experience. I don’t want to have to accept the blame for being a lazy person who just didn’t try hard enough in Math. But I really don’t want to have to accept the credit for being a virtuous and studious English student who worked harder than his peers. I know there were people who worked harder than I did in English, who poured their heart and soul into that course – and who still got Cs and Ds. To deny innate ability is to devalue their efforts and sacrifice, while simultaneously giving me credit I don’t deserve.

Meanwhile, there were some students who did better than I did in Math with seemingly zero effort. I didn’t begrudge those students. But if they’d started trying to say they had exactly the same level of innate ability as I did, and the only difference was they were trying while I was slacking off, then I sure as hell would have begrudged them. Especially if I knew they were lazing around on the beach while I was poring over a textbook.

I tend to think of social norms as contracts bargained between different groups. In the case of attitudes towards intelligence, those two groups are smart people and dumb people. Since I was both at once, I got to make the bargain with myself, which simplified the bargaining process immensely. The deal I came up with was that I wasn’t going to beat myself up over the areas I was bad at, but I also didn’t get to become too cocky about the areas I was good at. It was all genetic luck of the draw either way. In the meantime, I would try to press as hard as I could to exploit my strengths and cover up my deficiencies. So far I’ve found this to be a really healthy way of treating myself, and it’s the way I try to treat others as well.

Scott Alexander, “The Parable of the Talents”, Slate Star Codex, 2015-01-31.

September 26, 2016

July 12, 2016

QotD: Did our distant ancestors select for intelligence?

This is a special case of one of my favorite Damned Ideas, originally developed by John W. Campbell in the 1960s from some speculations by a forgotten French anthropologist. Campbell proposed that the manhood initiation rituals found in many primitive tribes are a selective machine designed to permit adulthood and reproduction only to those who can demonstrate verbal fluency and the ability to override instinctive fears on verbal command.

Campbell suggests that all living humans are descended from groups of hominids that, having evolved full-human mental capability in some of their members, found the overhead of supporting the dullards too high. So they began selecting for traits correlated with intelligence through initiation rituals timed for just as their offspring were achieving reproductive capacity; losers got driven out, or possibly killed and eaten.

Campbell pointed out that the common elements of tribal initiations are (a) scarring or cicatricing of the skin, opening the way for lethal infections, (b) alteration or mutilation of the genitals, threatening the ability to reproduce, and (c) alteration of the mouth and teeth, threatening the ability to eat. These seem particularly well optimized for inducing maximum instinctive fear in the subject while actually being relatively safe under controlled and relatively hygenic conditions. The core test of initiation is this: can the subject conquer fear and submit to the initiation on the basis of learned (verbal, in preliterate societies) command?

Campbell noticed the first order effect was to shift the mean of the IQ bell curve upwards over generations. The second-order effect, which if he noticed he didn’t talk about, was to start an arms race in initiation rituals; competing bands experimented with different selective filters (not consciously but through random variation). Setting the bar too low or too high would create a bad tradeoff between IQ selectivity and maintaining raw reproductive capacity. So we’re descended from the hominids who found the right tradeoff to push their mean IQ up as rapidly as possible and outcompeted the groups that chose less well.

It doesn’t seem to have occurred to Campbell or his sources, but this theory explains why initiation rituals for girls are a rare and usually post-literate phenomenon. Male reproductive capacity is cheap; a healthy young man can impregnate several young women a day, and healthy young men are instinct-wired to do exactly that whenever they can get away with it. Female reproductive capacity, on the other hand, is scarce and precious. So it makes sense to select the boys ruthlessly and give the girls a pass. Of course if you push this too far you don’t get enough hunters and fighters, but the right tradeoff pretty clearly is not 1-to-1.

Eric S. Raymond, “Selecting for intelligence”, Armed and Dangerous, 2003-11-14.

March 12, 2016

QotD: The bitter truth – the higher your IQ the worse your love life gets

I will have to use virginity statistics as a proxy for the harder-to-measure romancelessness statistics, but these are bad enough. In high school each extra IQ point above average increases chances of male virginity by about 3%. 35% of MIT grad students have never had sex, compared to only 13% of the average high school population. Compared with virgins, men with more sexual experience are likely to drink more alcohol, attend church less, and have a criminal history. A Dr. Beaver (nominative determinism again!) was able to predict number of sexual partners pretty well using a scale with such delightful items as “have you been in a gang”, “have you used a weapon in a fight”, et cetera. An analysis of the psychometric Big Five consistently find that high levels of disagreeableness predict high sexual success in both men and women.

If you’re smart, don’t drink much, stay out of fights, display a friendly personality, and have no criminal history — then you are the population most at risk of being miserable and alone. “At risk” doesn’t mean “for sure”, any more than every single smoker gets lung cancer and every single nonsmoker lives to a ripe old age — but your odds get worse. In other words, everything that “nice guys” complain of is pretty darned accurate. But that shouldn’t be too hard to guess…

Scott Alexander, “Radicalizing the Romanceless”, Slate Star Codex, 2014-08-31.

October 29, 2013

Colby Cosh on IQ

In his latest Maclean’s column, Colby Cosh talks about the odd evolutionary advantages that accrue as you get further from the equator:

A new study in the biometric journal Intelligence presents surprising data from Japan that reveal that IQ, imputed from standardized tests given to a large random sample of Japanese 14-year-olds, varies strongly and persistently with latitude. The Japanese are usually thought of — even by themselves — as being quite homogenous ethnically; the myth of the sturdy, super-cohesive “Yamato race” has not yet been entirely obtruded out of existence. But it turns out that the mean IQs of students in Japanese prefectures apparently vary from north to south by two-thirds of a standard deviation — a spread almost as large as the “race gaps” in cognitive performance which trouble education scholars in multicultural countries like ours. Sun-drenched Okinawans, as a group, do not test as well as the snowbound citizens of Akita.

It is an article of liberal faith that IQ is a bogus tool cooked up by white supremacists to justify imperialism and slavery. I am happy to nod along, but the monsters who developed IQ tests certainly never planned on creating strife between the two ends of Honshu Island. Kenya Kura’s study demonstrates the usual statistical connections between IQ and social outcomes, including physical height, income, and divorce and homicide rates. IQ may be a phony racist artifact, but if shoe size predicted life success as well as those stupid little logic puzzles do, every middle-class parent you know would have one of those Brannock foot-measuring thingies mounted proudly on the wall. That is why IQ persists in the top drawer of the psychometrics toolbox.

September 25, 2012

It’s not just your imagination: libertarians really are weird

Jonathan Haidt at the Righteous Mind summarizes a recent study published in PLoS ONE which looked at the psychology of libertarians (using conservatives and liberals as controls):

The findings largely confirm what libertarians have long said about themselves, but they also shed light on why some people and not others end up finding libertarian ideas appealing. Here are three of the major findings:

1) On moral values: Libertarians match liberals in placing a relatively low value on the moral foundations of loyalty, authority, and sanctity (e.g., they’re not so concerned about sexual issues and flag burning), but they join conservatives in scoring lower than liberals on the care and fairness foundations (where fairness is mostly equality, not proportionality; e.g., they don’t want a welfare state and heavy handed measures to enforce equality). This is why libertarians can’t be placed on the spectrum from left to right: they have a unique pattern that is in no sense just somewhere in the middle. They really do put liberty above all other values.

2) On reasoning and emotions: Libertarians have the most “masculine” style, liberals the most “feminine.” We used Simon Baron-Cohen’s measures of “empathizing” (on which women tend to score higher) and “systemizing”, which refers to “the drive to analyze the variables in a system, and to derive the underlying rules that govern the behavior of the system.” Men tend to score higher on this variable. Libertarians score the lowest of the three groups on empathizing, and highest of the three groups on systemizing. (Note that we did this and all other analyses for males and females separately.) On this and other measures, libertarians consistently come out as the most cerebral, most rational, and least emotional. On a very crude problem solving measure related to IQ, they score the highest. Libertarians, more than liberals or conservatives, have the capacity to reason their way to their ideology.

3) On relationships: Libertarians are the most individualistic; they report the weakest ties to other people. They score lowest of the three groups on many traits related to sociability, including extroversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. They have a morality that matches their sociability – one that emphasizes independence, rather than altruism or patriotism.

September 23, 2012

Are we really smarter than our great-grandparents?

An interesting article in the Wall Street Journal looks at the documented phenomenon of rapidly rising IQ in modern humans:

Advanced nations like the U.S. have experienced massive IQ gains over time (a phenomenon that I first noted in a 1984 study and is now known as the “Flynn Effect”). From the early 1900s to today, Americans have gained three IQ points per decade on both the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales and the Wechsler Intelligence Scales. These tests have been around since the early 20th century in some form, though they have been updated over time. Another test, Raven’s Progressive Matrices, was invented in 1938, but there are scores for people whose birth dates go back to 1872. It shows gains of five points per decade.

In 1910, scored against today’s norms, our ancestors would have had an average IQ of 70 (or 50 if we tested with Raven’s). By comparison, our mean IQ today is 130 to 150, depending on the test. Are we geniuses or were they just dense?

[. . .]

Modern people do so well on these tests because we are new and peculiar. We are the first of our species to live in a world dominated by categories, hypotheticals, nonverbal symbols and visual images that paint alternative realities. We have evolved to deal with a world that would have been alien to previous generations.

A century ago, people mostly used their minds to manipulate the concrete world for advantage. They wore what I call “utilitarian spectacles.” Our minds now tend toward logical analysis of abstract symbols — what I call “scientific spectacles.” Today we tend to classify things rather than to be obsessed with their differences. We take the hypothetical seriously and easily discern symbolic relationships.