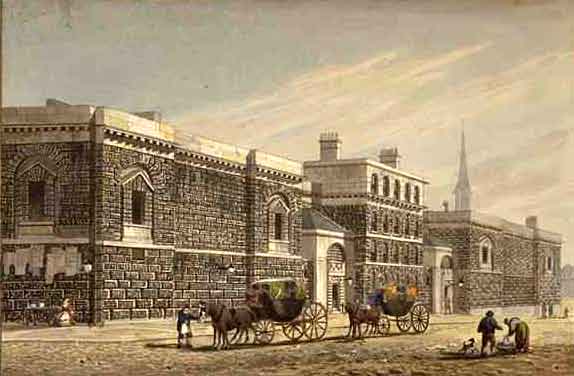

On this day, in 1851, Londoners were finally allowed to enter one of the most spectacular edifices to grace their city. Over the previous months they had watched it spring up in Hyde Park — the largest enclosed structure that had ever been built, and made with three hundred thousand of the largest panes of glass ever produced. Set against the blackened, soot-stained buildings of London, the massive glass edifice gleamed. It soon became known as the Crystal Palace.

Although it no longer exists — it was rebuilt in Sydenham, but the new version burnt down in the 1930s — the fame of the Crystal Palace endures. The same goes for the event that it was originally built for, the Great Exhibition of 1851. But, despite that name-recognition, I’ve found that most people don’t really know what the Great Exhibition was for. Yes, it attracted six million visitors in the space of just a few months — an estimated two million people, almost a tenth of the entire population of Great Britain, most of them returning again and again. But why? I must admit, despite having mentioned the event before in some of my work, I’d never really considered it properly before I started researching the history of the Society of Arts.

The idea of such an exhibition in Britain originated with the Society’s secretary in the 1840s, the civil engineer Francis Whishaw. He had seen the use of industrial exhibitions in France, as a means of catching up with Britain in terms of technology. Every few years since 1798, the French government had held an exhibition of its national industries in Paris. The state paid for everything — a grand temporary building, as well as the expenses of the exhibitors — and the head of state himself awarded medals and cash prizes for the bet works on display. Some of the very best exhibitors were even admitted to the Légion d’honneur, France’s highest order of merit. The benefits to exhibitors were so high that essentially every manufacturer wished to take part. In the days before GDP statistics, the exhibitions were thus an effective means of getting a detailed snapshot of the nation’s manufacturing capabilities. An exhibition served as the nation’s industrial audit.

[…]

Although there had been a few local exhibitions of industry in Britain in the late 1830s and early 1840s, there had been nothing on a national scale to rival the French ones. So Francis Whishaw began the work of getting the Society to organise such an event — a national exhibition of industry for Britain. His initial plan came to nothing, partly as he left the Society to take another job, but in the late 1840s the project was resurrected by a new member of the Society, a civil servant named Henry Cole. In fact, Cole almost entirely took over the Society in the late 1840s, turning it into an exhibition-holding organisation. It held exhibitions devoted to particular living artists, on ancient and medieval art, on inventions, and especially on industrial design — what Cole liked to call “art-manufactures”. And, at the 1849 national exhibition in Paris, he adopted an idea that had already been floated for some years by French officials: an international exhibition, to show the industry of all nations.

This was the crucial step. The idea of an international exhibition of industry appealed to the free trade movement in Britain, which had achieved success in the 1840s with the abolition of the Corn Laws. By displaying the products of other nations, the argument went, British consumers would demand that they be able to buy them more cheaply. And free trade would hopefully bring an end to war, too. Free trade campaigners argued that the productive classes of rival nations competed peacefully, simply by trying to outdo one another in the quality and quantity of what they produced. It was the landed aristocracy, they argued, who let the competition become violent, feeding their pride by causing destruction. Thus, a grand exhibition of the products of all nations — the Great Exhibition — would be a physical manifestation of free trade and international harmony: a “competition of arts, and not of arms”.

The Great Exhibition thus had many roles. It was partly born of national paranoia, about French industrial catch-up, as well as about Britain being the first to hold such an event. It was also about exciting competitive emulation between manufacturers, showing consumers what they did not know they wanted, and achieving world peace and free trade. It certainly spurred on dozens of examples of international cooperation. In fact, just the other day I discovered that the first international chess tournament was held in London to coincide with the exhibition. And it served as an audit of the world’s industries, allowing people to judge who was ahead and who was behind. It thereby gave domestic reformers the ammunition to push for changes in areas where Britain seemed to be falling behind, in areas like education, intellectual property, and design. But more on those another time.