Warren Meyer explains why his skepticism about the dangers of the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic kicked in quickly because it followed a very familiar pattern:

I have been skeptical about extreme global warming and climate change forecasts, but those were informed by my knowledge of physics and dynamic systems (e.g. feedback mechanics). I have been immensely skeptical of Elon Musk, but again that skepticism has been informed by domain knowledge (e.g. engineering in the case of the hyperloop and business strategy in the case of SolarCity and Tesla). But I have no domain knowledge that is at all relevant to disease transfer and pathology. So why was I immediately skeptical when, for example, the governor of Texas was told by “experts” that a million persons would die in Texas if a lock-down order was not issued?

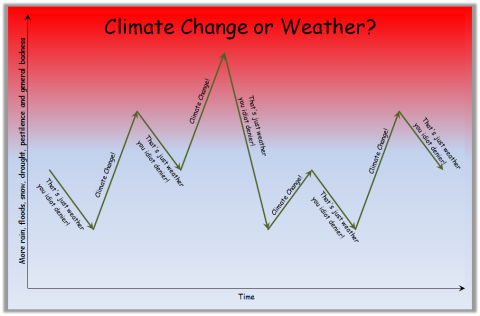

I think the reason for my skepticism was pattern recognition — I saw a lot of elements in COVID-19 modelling and responses that appeared really similar to what I thought were the most questionable aspects of climate science. For example:

- We seem to have a sorting process of “experts” that selects for only the most extreme. We start any such question, such as forecasting disease death rates or global temperature increases, with a wide range of opinion among people with domain knowledge. When presented with a range of possible outcomes, the media’s incentives generally push it to present the most extreme. So if five folks say 100,000 might die and one person says a million, the media will feature the latter person as their “expert” and tell the public “up to a million expected to die.” After this new “expert” is repetitively featured in the media, that person becomes the go-to expert for politicians, as politicians want to be seen by the public to be using “experts” the public recognizes as “experts.”

- Computer models are converted from tools to project out the implications of a certain set of starting hypotheses and assumptions into “facts” in and of themselves. They are treated as having a reality, and a certainty, that actually exceeds that of their inputs (a scientific absurdity but a media reality I have observed so many times I gave it the name “data-washing”). Never are the key assumptions that drive the model’s behavior ever disclosed along with the model results. Rather than go on forever on this topic, I will refer you to my earlier article.

- Defenders of alarmist projections cloak themselves in a mantle of being pro-science. Their discussions of the topic tend to by science-y without being scientific. They tend to understand one aspect of the science — exponential growth in viruses or tipping points in systems dominated by positive feedback. But they don’t really understand it — for example, what is interesting about exponential growth is not the math of its growth, but what stops the growth from being infinite. Why doesn’t a bacteria culture grow to the mass of the Earth, or nuclear fission continue until all the fuel is used up? We are going to have a lot of problem with this after COVID-19. People will want to attribute the end of the exponential growth to lock-downs and distancing, but it’s hard to really make this analysis without understanding at what point — and there is a point — the virus’s growth would have turned down anyway.

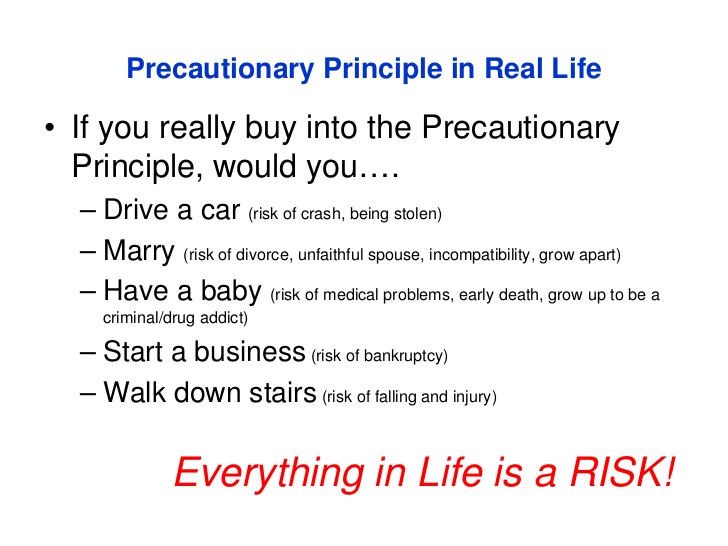

- Alarmists who claim to be anti-science have a tendency to insist on “solutions” that have absolutely no basis in science, or even ones that science has proven to be utterly bankrupt. Ethanol and wind power likely do little to reduce CO2 emissions and may make them worse, yet we spend billions on them as taxpayers. And don’t get me started on plastic bag and straw bans. I am willing to cut COVID-19 responses a little more slack because we don’t have the time to do elaborate studies. But just don’t tell me lockdown orders are science — they are guesses as to the correct response. I live in Phoenix where it was sunny and 80F this weekend. We are on lockdown in our houses. I could argue that ordering everyone out into the natural disinfectant of heat and sunlight for 2 hours a day is as effective a response as forcing families into their houses (initial data, though it is sketchy, of limited transfer of the virus in summertime Australia is interesting — only a small portion of cases are from community transfer. By comparison less than a half percent of US cases from travel).