Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry @pegobry_en

This is obvious, but: Elon breaks libs’ brains because he is the living vindication of the Great Man theory of history. Literally nothing he built would have existed without him, and without him clearly exhibiting superior intelligence and indomitable will.Not so fast.

I’m here to tell you, because I lived it, that the experience of being the “Great Man” who changed history can feel very different from the inside.

I’m not going to try to speak for Elon. Maybe he feels like a colossus out of Thomas Carlyle. I’ll just say that I didn’t feel like that when I was doing my thing, and I’m doubtful that he does more than a small part of the time.

Somebody was going to take the concept of “open source” to the mainstream fairly soon after general access to the Internet started to happen in the mid-1990s. But it didn’t have to be me; you get steam-engines when it’s steam-engine time, and it was time. Dennard scaling and cheap wide-area networking were the underlying drivers. Conditions like that generate ESR-equivalents.

Now it’s time for rockets to Mars. The drivers include extremely cheap and powerful computing, 3-D printing, and advances in both metallurgy and combustion chemistry. Conditions like this generate Elon-equivalents.

It is more than possible to look like the Great Man from the outside but to feel like — to know — that you are almost at the mercy of currents of change much larger than yourself. Yes, you have some ability to shape outcomes. And you can fail, leaving the role to the next person to notice the possibilities.

If Elon is like me, he sometimes plays the autonomous Great Man in order to get the mission done, because he knows that the most effective way to sell ideas is to be a charismatic prophet of them. But if he’s like me, he also feels like the mission created him to make itself happen, and if he fails or breaks the mission will raise up another prophet by and by.

I’m not claiming the Great Man theory is entirely wrong — it takes some exceptional qualities to be an Elon, or even a lesser prophet like me — but it’s incomplete. Great Men don’t entirely create themselves, they are thrust upwards and energized by missions that are ready to happen.

ESR, Twitter, 2024-10-31.

February 24, 2025

QotD: Great Men when it’s time to do x

November 24, 2024

Trump breaks the electoral pattern that had persisted for decades

In Quillette, Jason Garshfield outlines the “traditional” pattern of presidential elections and identifies the relatively few breaks in that pattern and how Donald Trump represents a major disruption compared to what outside observers might have expected to see:

… Yet the symbolic power of the presidency is paramount. We speak of the 1980s as the Reagan Era and the 1990s as the Clinton Era, not the “Tip O’Neill Era” or the “Newt Gingrich Era”. The presidency represents control over the federal government, and ultimately over the spirit and the direction of the nation. It is the highest political prize, and a party consistently denied the presidency will not remain a satisfied player in the system, even if they achieve political success on other meaningful fronts. This is dangerous in a nation where mutual assent is a prerequisite for the smooth functioning of a free and fair electoral system.

Trump’s 2024 victory does not feel as shocking as his 2016 victory did. After all, we’ve seen this show before. But 2024 is a more remarkable coup than 2016. Back then, Trump’s victory did not buck the prevailing trend. This time, he won against that trend and shattered the pattern.

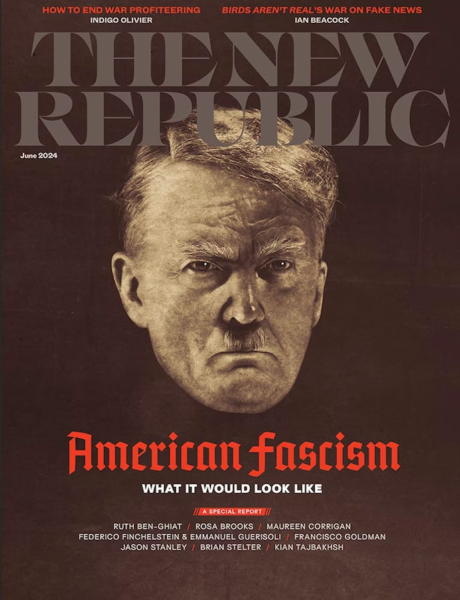

Some have argued that Trump’s indomitable force of personality, demonstrated in the way in which he has refashioned American politics in his image over the past decade, vindicates the Great Man Theory of History. For instance, Yair Rosenberg, writing for The Atlantic in 2022, commented that Trump’s “personal idiosyncrasies — and, I would argue, malignancies — altered the course of American history in directions it otherwise would not have gone”. To Rosenberg, this represented a turn for the worse, but many of Trump’s supporters would say the same, while casting it in a more positive light. As with Napoleon Bonaparte, one cannot confidently state that if Trump had never been born, someone like him would have done what he did.

Elsewhere in this magazine, I compare Donald Trump to the Mule, a character in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation stories who, with his unique superpower of mind control, manages to undo the entire Seldon Plan which had been designed to direct the future of the galaxy. In Asimov’s fictional social science of psychohistory, humans are compared to molecules within a gas: the path of each individual molecule is unpredictable, but the movement of the gas as a whole can be predicted. But the psychohistorians assume that no one molecule can ever have a significant effect on the whole — and they are mistaken.

Trump is a particle that defies measurement. It is as though Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle applies to him: you can know where he is, or how fast he is going, but never both at the same time. Once you think you have him pinned down to a fixed point in the cosmos, he throws your calculations into chaos. This drives his opponents crazy and imbues his most fervent supporters with a near-messianic belief that he will triumph against any odds.

Social scientists tend to hate the Great Man Theory of History because it renders their work entirely meaningless. No matter how strong certain social forces may be, they can ultimately be dispensed with at any time by unpredictable mighty figures. As a result, the future is frighteningly unknowable. But both Great Man Theory and historical determinism have dire implications. Either individuals are irrelevant, or else we live in an unknowable and irrational universe, which unfolds according to no fixed laws. Neither theory allows rationalism and individualism to coexist.

The durability of the eight-year pattern in American politics seems to provide strong evidence against the Great Man Theory. Many of the leaders and almost-leaders of the United States since 1952 have been outsized personalities, yet the sociological paradigm suggests that their personal charisma had little impact on their success or failure. In this view, neither Barack Obama’s charm nor John McCain and Mitt Romney’s lack of charm radically influenced the outcomes of the 2008 and 2012 elections. It was simply time for a Democrat to win, and McCain and Romney might as well not have run. For that matter, both parties might as well have saved their energy and agreed to simply exchange places every eight years — that is, if we accept historical determinism as the driving factor.

Before Trump, only two other figures in postwar America came close to being Great Men. They were the finalists of the 1980 election: Ronald Reagan, who managed to win against the pattern and usher in twelve straight years of Republican control, and Jimmy Carter, who lost the election he should have won. It is debatable as to whether the 1980 election was more a story of Carter’s weakness or Reagan’s strength, but both undoubtedly played a role. Now Trump has become both Carter and Reagan, the unexpected loser of one election and the unexpected winner of another.

June 16, 2024

QotD: Napoleon Bonaparte – the great man?

John: … I think my favorite big picture thing about the Roberts book [Napoleon the Great] is the way it cuts through two centuries of Anglophone ignorance and really shows you why the continent flung itself at this man’s feet. The pop culture image of Napoleon as this little bumbling dictator is so clearly a deliberate mystification by the perfidious British who felt inadequate in the shadow of this guy they (barely) beat.

Remember, the real Napoleon was so impressive he literally caused a crisis in 19th century philosophy! Everybody had carefully worked out their little theories, later exemplified by Tolstoy, about how human agency doesn’t matter in history and everything is just the operation of vast impersonal forces like the grinding of tectonic plates, and then boom this guy shows up and the debate springs to life again. You know it’s real when two guys as different as Nietzsche and Dostoevsky are both grappling with what we can learn from somebody’s existence. And I think Raskolnikov’s unhealthy Napoleon fanboyism was supposed to be a bit of a satire of some very real intellectual currents among the European and Russian intelligentsia.

So what do you think? Does Napoleon vindicate the great man theory of history? I’m still working out my own answer to this, which I briefly allude to in my review of Zhuchkovsky’s book. Basically, I think we can transcend the traditional dichotomy by constructing a political/military analogue of the Schumpeter/Kirzner theory of entrepreneurship. Vast, impersonal forces (such as technological progress or structural economic changes) can create opportunities — in fact they’re pretty much the only thing that can, because the force required to reconfigure society is usually far beyond what any person or group can manage.

But once the opportunity is there, it takes a lot less raw power to act on it, assuming you can recognize it. Imagine a process of continental drift that slowly, slowly raises a mountain-sized boulder out of the ground, and every year it’s inching closer to this precipice, until finally it teeters on the edge. A human being could never have done that, it would be far too heavy, but once it’s up there, there might be a narrow window, a few precious moments, when a solid shove by somebody sufficiently perceptive and motivated can direct and harness this unimaginable force.

So the question is: what made Europe so ripe for Disruption (TM) at that moment? Obviously the French Revolution, and there were some pretty important changes in the nature of warfare too. What else?

Jane: Well, you know what I’m going to say: it’s the Enlightenment, stupid.

I was going to compare Napoleon to, say, Odoacer, but I don’t think the analogy actually holds. The Goths were conquerors from outside; their approach, their whole worldview, was very different from the Romans’.1 But Napoleon is extremely inside. The people he comes from are not actually all that different from the ancien régime — they’re feuding hill clans, but they’re aristocratic feuding hill clans — and yet he’s so thoroughly a creature of Enlightenment modernity that even when he’s engaging in the time-honored feuding hill clan pastime of resisting integration by the metropole he’s doing it by writing pamphlets. He might be a Corsican nationalist but he’s been intellectually colonized by France. Or, more accurately, by the elements of French culture that are in the process of undermining and overthrowing it.

I think you’re right about political entrepreneurship. (So here we see the Psmiths wimp out and answer the great man/impersonal force dichotomy “yes”.) It’s perhaps more neatly summed up by that famous Napoleon quip: “I saw the crown of France lying on the ground, so I picked it up with my sword”. Which: based. But also, if we’re going to continue his metaphor, he didn’t knock the crown onto the ground. Everything was already irredeemably broken before he got there. And this, I think, distinguishes him from the Germanic conquerors, who found something teetering and gave it a final push. Caesar, similarly, came up in the old order but dealt it its death blow.

But back to the Enlightenment: the crown is on the ground because the culture that held it up has fallen apart, and it’s fallen apart because gestating in its innards was an entirely different culture that’s finally burst its skin like a parasitic wasp and emerged into the light of day. A lazy reading of history sees Napoleon with a crown giving people titles and building palaces and goes “ooh, look, he’s just like the ancien régime“, but this is dumb. Napoleon is obsessed with modernizing and streamlining. He wants to wipe away the accumulated cruft of a thousand years of European history and build something smarter and cleaner and more rational. He’s just better at organization and psychology than the revolutionaries were. The French Revolution (and the total failure of the Directory) created the material conditions, but the entire intellectual milieu that made the French Revolution possible also made it possible for people to look at Napoleon and go “whoa, nice”.

Jane and John Psmith, “JOINT REVIEW: Napoleon the Great, by Andrew Roberts”, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith’s Bookshelf, 2023-01-21.

1. There’s some very interesting stuff on this, and about later efforts from both cultures to bridge the gap, in Bryan Ward-Perkins’ The Fall of Rome: And the End of Civilization.

November 9, 2022

QotD: Was Temujin (aka Genghis Khan/Chinggis Khan) a “great man”?

Take, for instance, Chinggis Khan (born Temujin; I am going to use Temujin here to mean the man himself and Chinggis Khan to mean his impact as a ruler once the Mongols were fully united). The conditions for Chinggis Khan were not new in 1158; the basic technological factors with made the Steppe way of war possible had existed in the Eurasian Steppe for at least two thousand years by the time Temujin was born. Political fragmentation was also an important factor, but this was hardly the first time that nearby China had been politically fragmented (at the very least the periods 771-221BC, 220-280AD, 304-589 and 907 through to Temujin’s birth in 1158 all qualify) and the steppe had effectively always been politically fragmented. Our evidence for life on the steppe is limited (we’ll come back to this in a second) but by all appearances the key social institutions Temujin either relied on or dismantled were all centuries old at least at his birth.

What had been missing for all that time was Temujin. To buy into the strongest form of “cliodynamics” is to assume that the Steppe always would have produced a Temujin (in part because his impact is so massive that a “general law” of history which cannot predict an event of such titanic import is not actually a functional “general law”). And to be fair, it had produced nearly Temujins before: Attila, Seljuk, etc. But “nearly” here isn’t good enough because so many of the impacts of Chinggis Khan depend on the completeness of his conquests, on a single state interested in trade controlling the entire Eurasian Steppe without meaningful exception. The difference between Temujin and almost-Temujin (which is just basically “Jamukha”) is history-shatteringly tremendous, given that both gunpowder and the Black Death seem to have moved west on the roads that Chinggis opened and the subsequent closure of those routes after his empire fragmented seem to have been a major impetus towards European seaborne expansion.

Moreover, it is not at all clear that, absent Temujin in that particular moment – keeping in mind that Temujin hadn’t appeared in any other moment – that there would have inevitably risen a different Temujin sometime later. After all, for two millennia the steppe had not produced a Temujin and by 1158, the technological window for it to do so was already beginning to close as humans in the agrarian parts of the world (read: China) had already begun harnessing chemical energy in ways that would eventually come to rob the nomad of much of his strength. If Temujin dies as a boy – as he very well might have! – it is not at all clear he’d be replaced before that window closed; his most obvious near peer was Jamukha, but here personalities matter: Jamukha was committed to the old Mongol social hierarchy (this was part of why he and Temujin fell out) and was so unwilling to do the very things that made Chinggis Khan’s great success possible (obliterating clan distinctions and promoting based on merit rather than family pedigree). Jamukha could have been another Seljuk, but he could not have been another Chinggis Khan and in this case that would make all of the difference.

To get briefly into a bit of historical theory, Chinggis is an individual whose actions in life fundamentally altered many of what the “Annales School” of history would call the structures and mentalités of his (and subsequent) times. The Annales school likes to view history through a long duration lens (longue durée) and focus on big shaping structures like climate, geography, culture and so on. The difference between this and cliodynamics is that Annales thinkers propose to describe rather than predict, so it is not fatal to their method if there are occasional, sudden, unpredictable alterations to those underlying structures – indeed those are the moments which are most interesting. But it is fatal to a cliodynamics perspective, which does aim for prediction since “our prediction is absolutely right unless it is completely wrong” hardly inspires confidence and a “general law” of anything is only a “general law” in that it is generally applicable not merely to the past but also to the future.

In short, Chinggis Khan wasn’t a commodity; he couldn’t be replaced by any other Mongol warrior. And figures like that abound through history (for Roman history, it matters greatly for instance that Marius, Sulla, Pompey, Caesar and Octavian had very different personalities when they found themselves in a position to dominate the Republic with military force). Moreover, the figures like that who we think of, generally capital-g “Great Men”, are hardly the only such individuals like that. They’re only the ones we can see. What of, for instance, the old Argive mother – her name lost to history – who killed Pyrrhus of Epirus, considered the greatest general of his generation, with a lucky throw of a roofing tile, both ending his career but also setting in motion a chain of events where the power vacuum left by Epirus would be filled by Carthage and Rome in a way that would bring those former allies (allied against Pyrrhus, in fact) into a shattering conflict which would then pave the way for Roman dominance in the Mediterranean? History must be full of innumerable such figures whose actions created and closed off courses of events in ways we can never know; how do we know that there wasn’t some would-have-been Temujin on the steppe in 100AD but who was killed in some minor dispute so very minor it leaves literally no evidence behind?

(The fancy way of putting the influence of all of those factors, both the big structural ones and the little, subject-to-chance ones, is to say “history is contingent” – that is, the outcomes are not inevitable but are subject to many forces large and small, many of which the lack of evidence render historically invisible.)

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday: October 15, 2021”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-15.

July 25, 2022

QotD: Napoleon Bonaparte, the Great Man’s Great Man

The point is, a culture can survive an incompetent elite for quite a while; it can’t survive a self-loathing one. This is because the Great Man theory of History, like everything in history, always comes back around. History is full of men whose society doesn’t acknowledge them as elite, but who know themselves to be such. Napoleon, for instance, and isn’t it odd that as much as both sides, Left and Right, seem to be convinced that some kind of Revolution is coming, you can scour all their writings in vain for one single mention of Bonaparte?

That’s because Napoleon was a Great Man, possibly the Great Man — a singularly talented genius, preternaturally lucky, whose very particular set of skills so perfectly matched the needs of the moment. There’s no “social” explanation for Napoleon, and that’s why nobody mentions him — the French Revolution ends with the Concert of Europe, and in between was mumble mumble something War and Peace. The hour really did call forth the man, in large part, I argue, because the Directory was full of men who were philosophically opposed to the very idea of elitism, and couldn’t bear to face the fact that they themselves were the elite.

Since our elite can’t produce able leaders of itself, it will be replaced by one that can. When our hour comes — and it is coming, far faster than we realize — what kind of man will it call forth?

Severian, “The Man of the Hour”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-05-22.

December 1, 2020

QotD: Elon Musk as a real life Delos D. Harriman

The “key story” [in Robert Heinlein’s “Future History” stories] I just mentioned is called “The Man Who Sold The Moon.” And if you’re one of the people who has been polarized by the promotional legerdemain of Elon Musk — whether you have been antagonized into loathing him, or lured into his explorer-hero cult — you probably need to make a special point of reading that story.

The shock of recognition will, I promise, flip your lid. The story is, inarguably, Musk’s playbook. Its protagonist, the idealistic business tycoon D.D. Harriman, is what Musk sees when he looks in the mirror.

“The Man Who Sold The Moon” is the story of how Harriman makes the first moon landing happen. Engineers and astronauts are present as peripheral characters, but it is a business romance. Harriman is a sophisticated sort of “Mary Sue” — an older chap whose backstory encompasses the youthful interests of the creators of classic pulp science fiction, but who is given a great fortune, built on terrestrial transport and housing, for the purposes of the story.

Our hero has no interest in the money for its own sake: in late life he liquidates to fund a moon rocket, intending to take the first trip himself, because he is convinced the future of humanity depends on extraterrestrial expansion of the human species. (Also, the guy just really loves the moon.)

The actual stuff of the story consists of the financial and promotional chicanery that Harriman uses to leverage his personal investment. Harriman uses sharp dealing with governments, broadcasters, political groups: he plants fake news about diamonds on the moon to blackmail (a disguised version of) the de Beers cartel, and terrorizes companies with the threat of using the moon to advertise for competitors. He is, in short, not afraid to use questionable means to achieve a worthwhile higher end, and does not — Musk haters take note! — recoil from actual fraud.

Heinlein didn’t provide for live broadcasting of his imagined lunar mission, which is almost an afterthought in his Great Man business yarn. TV cameras were, like computers, one of his blind spots. But if he had thought to make Harriman the owner of a fancy-sportscar manufacturing concern, and if he had thought to have Harriman put a car in solar (trans-Martian!) orbit as one of his publicity stunts, that would have been there in “The Man Who Sold The Moon.” Selling the moon is just what Musk is doing. Except the moon is a tad worked-over as a piece of intangible property, so we get Mars instead.

Colby Cosh, “Heinlein’s monster? The literary key to Elon Musk’s sales technique”, National Post, 2018-02-12.

July 25, 2017

Great Man Theory? No. Impersonal Forces of History? No. How about the Bond Villain Theory?

Charles Stross may have cracked the mystery of what the heck is happening in our particularly odd time period:

History: is it about kings, dates, and battles, or the movement of masses and the invisible hand of macroeconomics?

There’s something to be said for both theories, but I have a new, countervailing theory about the 21st century (so far); instead of the traditional man on a white horse who leads the revolutionary masses to victory, we’ve wandered into a continuum dominated by Bond villains.

Consider

threefourfive, taken at random:Mr X: leader of a chaotic former superpower with far too many nuclear weapons, Mr X got his start in life as an agent of

SMERSHthe KGB. Part of its economic espionage directorate, tasked with modernizing a creaking command economy in the 1980s, Mr X weathered the collapse of the previous regime and after a turbulent decade of asset stripping rose to lead a faction of billionaire oligarchs, robber barons, and former secret policemen. Mr X trades on his ruthless reputation — he is said to have ordered a defector murdered by means of a radioisotope so rare that the assassination consumed several months’ global production — and despite having an official salary on the order of £250,000 he has a private jet with solid gold toilet seats and more palaces than you can shake a stick at. Also nuclear missiles. (Don’t forget the nuclear missiles.) Said to be dating the ex-wife of Mr Y. Exit strategy: change the constitution to make himself President-for-Life. Attends military parades on Red Square, natch. Bond Villain Credibility: 10/10Mr Y: Australian multi-billionaire news magnate. (Currently married to a former supermodel and ex-wife of Mick Jagger.) Owns 80% of the news media in Australia and numerous holdings in the UK and USA, including satellite TV channels, radio stations, and newspapers. Reputedly had Arthur C. Clarke on speed-dial for advice about the future of communications technology. Was the actual no-shit model upon whom Elliot Carver, the villain in “Tomorrow Never Dies”, the 18th Bond movie, was based. Exit strategy: he’s 86, leave it all to the kids. Bond Villain Credibility: 10/10

[…]

I think there’s a pattern here: don’t you? And, more to the point, I draw one very useful inference from it: if I need to write any more near-future fiction, instead of striving for realism in my fictional political leaders I should just borrow the cheesiest Bond villain not already a member of the G20 or Davos.