[Princesses] think of themselves as Strong, Independent Women, even while saying “I like a man to open doors and pay for everything — and treat me like a princess!” No, dear, if a man opens doors for you he’s treating you like a simpleton and if he pays for everything, he’s treating you like a hooker. (The crossover between the princess look and the hooker look, as the late Barbara Cartland grotesquely illustrated, is considerable.) And it’s a man knowing that you can be bought with a dinner and a pair of shoes which leads to him so frequently mugging you off — royally — in favour of a better bargain. Back on the pink plastic shelf you go!

How do you spot a Princess? She’ll be keen on pampering to an extent which indicates to the casual onlooker that her natural self must be extraordinarily rank if it takes such effort and expense to keep in check. (Princesses shouldn’t be confused with Professional Beauties, most of whom retain a healthy contempt for the business of exchanging physical gifts for fiscal rewards, from Hedy Lamarr saying “Any girl can be glamorous — all you have to do is stand still and look stupid” to the catwalk models who invariably live in jeans and sneakers after shrugging off the stupid clothes which Princesses pine for.)

The Princess believes that retail therapy is the answer to everything, even though the rest of us avert our eyes from this most obvious manifestation of the essential hollowness of a life that an over-enthusiasm for clothes-shopping invariably indicates in anyone out of their teens. They’ll have long nails, ostensibly to show that they’re ladies of leisure, but signalling to the rest of us that they’re very likely parasites with low sex-drives. They like big weddings — and as a liking for big weddings often goes hand in hand with humourlessness, they often have very short marriages. They are in short practitioners of the Violet Elizabeth Bott school of feminism – less about equal rights and fulfilling one’s potential than about stamping your foot till you get what you want.

They dislike men, seeing them not as flesh-and-blood people so much as platinum-and-titanium meal-tickets, and they mistrust women, seeing them as competition. An ageing Princess is more than likely to end up lonely — and with no life of the mind to comfort her, this loneliness may make her mentally addled at a comparatively young age. Once the sheen is off her skin, the Princess has nothing that would make one seek her out; like a lot of people over-keen on spangles and glitter, they are at heart rather drab people — drains not radiators, personality-wise — who never make things happen or drive things forward but rather wait to be rescued. They tend to find themselves eternally in the passenger seat of their life’s journey, stranded on the hard shoulder with their souvenirs, waiting in vain for hunky help to arrive.

Julie Burchill, “The Princess generation needs to grow up”, The Spectator, 2017-07-18.

August 26, 2019

QotD: Princesses

December 21, 2016

January 13, 2014

Defining glamour

Virginia Postrel is interviewed at Paleofuture:

I think of glamour as a form of communication, persuasion, rhetoric. What happens is you have an audience and you have an object — something glamorous. It could be a person, could be a place, could be an idea, could be a car — and when that audience is exposed to that object a specific emotion arises, which is a sense of projection and longing.

Glamour is like humor. You get the same sort of thing in the interaction between an audience and something funny. It’s just the emotion that’s different. So when you see something that strikes you as glamorous, or you hear about or see something glamorous, it makes you think, “If only. If only life could be like that. If only I could be there. If only I could be that person, or with that person. If only I could drive that car, fly in that spaceship, or whatever.”

And there are always three elements that create that sensation: one is a promise of escape and transformation. A different, better life in different, better circumstances. The other is there is a sense of grace, effortlessness, all the flaws and difficulties are hidden. And the third is mystery. Mystery both draws you in and enhances the grace by hiding things.

Another way of thinking about glamour is to think about the origins of the word glamour. Glamour originally meant a literal magic spell that made people see something that wasn’t there. It was a Scottish word. A magician would cast a glamour over people’s eyes and they would see something different. As the word became a more metaphorical concept, it always retained that sense of magic and illusion. And where the illusion lies is in the grace; in the disguising of difficulties and flaws.

November 20, 2013

Jacqueline Kennedy and the Camelot myth

Virginia Postrel on the legacy of Jacqueline Kennedy:

When she was 22, the future Jacqueline Kennedy won a Vogue contest with an essay in which she dreamed of being “a sort of Overall Art Director of the Twentieth Century.” As first lady, she proved herself a genius at visual persuasion. She crafted her own image, refined her husband’s, re-created the White House’s, and even shaped America’s abroad.

Her most evocative and enduring image-making came when John F. Kennedy was assassinated, 50 years ago this week. She art-directed the funeral’s pageantry and then, in an interview with T.H. White for Life magazine, memorably linked her husband to one of the most powerful legends in the English-speaking world. Jackie created the myth of the Kennedy administration as Camelot: the lost golden age that proved ideals could become real.

The Arthurian legends traditionally operate as what the cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken calls “displaced meaning.” Every culture, he observes, maintains ideals that can never be fully realized in everyday life, from Christian charity to economic equality. Yet for all their empirical failings, such cultural ideals supply essential purpose and meaning, offering identity and hope. To preserve and transmit them, cultures develop images and stories that portray a distant world in which their ideals are realized — a paradise, a utopia, a golden age, a promised land, a world to come. Camelot is such a setting.

“When they are transported to a distant cultural domain,” McCracken writes, “ideals are made to seem practicable realities. What is otherwise unsubstantiated and potentially improbable in the present world is now validated, somehow ‘proven,’ by its existence in another, distant one.”

[…] The Kennedy administration ended with sudden violence from without, making Jackie’s analogy doubly potent. It suggested a parallel with a legendary Golden Age while simultaneously implying that, left to itself, this new Golden Age might have continued indefinitely. This Camelot was pure glamour: a frozen moment, its flaws and conflicts obscured.

Glamour invites projection. For 50 years, Americans of various persuasions have imagined their ideals embodied in a Camelot that might have been. Advocates of a vigorous Cold War foreign policy claim John Kennedy. So do their opposites. He did less for the civil-rights movement than his unglamorous successor, Lyndon Johnson, yet in imagination he would have done more. Above all, people imagine that somehow a living Kennedy would have prevented the tumult of the 1960s.

November 9, 2013

Virginia Postrel on the persistence of glamour

At the Daily Beast, Virginia Postrel argues that far from being dead, glamour is still a powerful force in our lives:

In a world that prizes transparency, honesty, and full disclosure, the very idea seems out of place. Glamour is an illusion that conceals flaws and distractions. It requires mystery and distance, lest too much information breaks the spell. How can its magic possibly survive in a world of tweeting slobs?

But glamour does in fact endure. It is far more persistent, pervasive, and powerful than we realize. We just have trouble recognizing it, because it has so many different incarnations, many of which have nothing to do with Hollywood or fashion.

Glamour isn’t just a style of dress or a synonym for celebrity. Like humor, it’s a form of communication that triggers a distinctive emotional response: a sensation of projection and longing. What we find glamorous, like what we find funny, depends on who we are.

One person who yearns to feel special finds glamour in the image of U.S. Marines as “the few, the proud,” while another dreams of getting into the city’s hottest club and yet another imagines matriculating at Harvard. For some people, a glamorous vacation means visiting a cosmopolitan capital with lots to do and see. For others, it means a tranquil beach or mountain cabin. The first group yearns for excitement, the second for rest. All of these things are glamorous — but to different people.

October 25, 2013

The glamour of big IT projects

Virginia Postrel on the hubris of the Obamacare project team:

The HealthCare.gov website is a disaster — symbolic to Obamacare opponents, disheartening to supporters, and incredibly frustrating to people who just need to buy insurance. Some computer experts are saying the only way to save the system is to scrap the current bloated code and start over.

Looking back, it seems crazy that neither the Barack Obama administration nor the public was prepared for the startup difficulties. There’s no shortage of database experts willing to opine on the complexities of the problem. Plenty of companies have nightmarish stories to tell about much simpler software projects. And reporting by the New York Times finds that the people involved with the system knew months ago that it was in serious trouble. “We foresee a train wreck,” one said back in February.

So why didn’t the administration realize that integrating a bunch of incompatible government databases into a seamless system with an interface just about anyone could understand was a really, really hard problem? Why was even the president seemingly taken by surprise when the system didn’t work like it might in the movies?

We have become seduced by computer glamour.

Whether it’s a television detective instantly checking a database of fingerprints or the ease of Amazon.com’s “1-Click” button, we imagine that software is a kind of magic — all the more so if it’s software we’ve never actually experienced. We expect it to be effortless. We don’t think about how it got there or what its limitations might be. Instead of imagining future technologies as works in progress, improving over time, we picture them as perfect from day one.

November 20, 2010

The use of glamour to advance weak economic ideas

Virginia Postrel highlights the power of glamour even in technical and economic arguments:

When Robert J. Samuelson published a Newsweek column last month arguing that high-speed rail is “a perfect example of wasteful spending masquerading as a respectable social cause,” he cited cost figures and potential ridership to demonstrate that even the rosiest scenarios wouldn’t justify the investment. He made a good, rational case — only to have it completely undermined by the evocative photograph the magazine chose to accompany the article.

The picture showed a sleek train bursting through blurred lines of track and scenery, the embodiment of elegant, effortless speed. It was the kind of image that creates longing, the kind of image a bunch of numbers cannot refute. It was beautiful, manipulative and deeply glamorous.

The same is true of photos of wind turbines adorning ads for everything from Aveda’s beauty products to MIT’s Sloan School of Management. These graceful forms have succeeded the rocket ships and atomic symbols of the 1950s to become the new icons of the technological future. If the island of Wuhu, where games for the Wii console play out, can run on wind power, why can’t the real world?

Policy wonks assume the current rage for wind farms and high-speed rail has something to do with efficiently reducing carbon emissions. So they debate load mismatches and ridership figures. These are worthy discussions and address real questions.

But they miss the emotional point.

I guess it’s a sign of weakness for the economic folks that they don’t realize how much of the battle for public support can rest on non-economic factors. You might be able to win all the technical battles, but it’s often the emotional factors that determine victory overall.

April 22, 2010

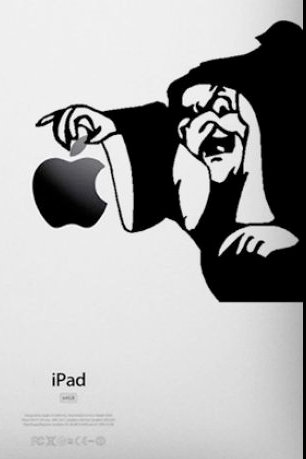

The iPad is “the ultimate Steve Jobs device”

I’m still quite happy with my iPhone, although I’ll pay attention when the next annual hardware refresh is released. I don’t quite “get” the attraction of the iPad, but perhaps it’s because I’m not typically swayed by glamour. Eric Raymond is amazed, but not at the device itself. He’s amazed at how closesly it approaches the Platonic ideal of a Steve Jobs device:

The iPad is the ultimate Steve Jobs device — so hypnotic that not only do people buy one without knowing what it’s good for, they keep feeling like they ought to use it even when they have better alternatives for everything it does. It’s a triumph of style over substance, cool over utility, form over actual function. The viral YouTube videos of cats and two-years-olds playing with it speak truth in their unsurpassable combination of draw-you-in cuteness with utter pointlessness. It’s the perfect lust object of postmodern consumerism, irresistibly attractive but empty — you know you’ve been played by the marketing and design but you don’t care because your complicity in the game is part of the point.

This has to be Steve Jobs’s last hurrah. I predict this not because he is aging and deathly ill, but because he can’t possibly top this. It is the ne plus ultra of where he has been going ever since the Mac in 1984, with his ever-more obsessive focus on the signifiers of product-design attractiveness. And it’s going to make Apple a huge crapload of money, no question.

Sorta related, from BoingBoing:

August 28, 2009

Ted Kennedy

Virginia Postrel looks at the differences between the glamour of the JFK and RFK images and the non-glamorous career of Ted Kennedy:

Ted was the Kennedy who lived. He was, as a result, the Kennedy who wasn’t glamorous.

Jack is forever young and forever whatever his adoring fans imagine him to be: the president who would have gotten us out of Vietnam (rather than the one who got us in) or the original supply-sider (rather than a textbook Keynesian), the ideal combination of Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama. We learned decades ago about Jack’s compulsive womanizing, but it is those selective images of the beautiful family that remain in collective memory. Life recorded no adulteries, no dirty tricks, no secret injections. The JFK of memory is a man of vigor, not an Addison’s patient dependent on steroids, painkillers, and anti-spasmodics. He is the personification of political glamour.

Bobby, too, is glamorous — the tough guy turned symbol of youth and idealism, more photogenic than Gene McCarthy and more mythic. No one wonders how he would have held together the fractious Democratic Party of 1968, because he never had to. Like his brother, RFK is a persona, not a person, all hope and promise and projection.

In an age of cynicism and full disclosure, political glamour is a rarity — not because politicians lack good looks or wealth or celebrity but because we know too much about them. We too easily see their flaws and imagine even more than the flaws we do see.