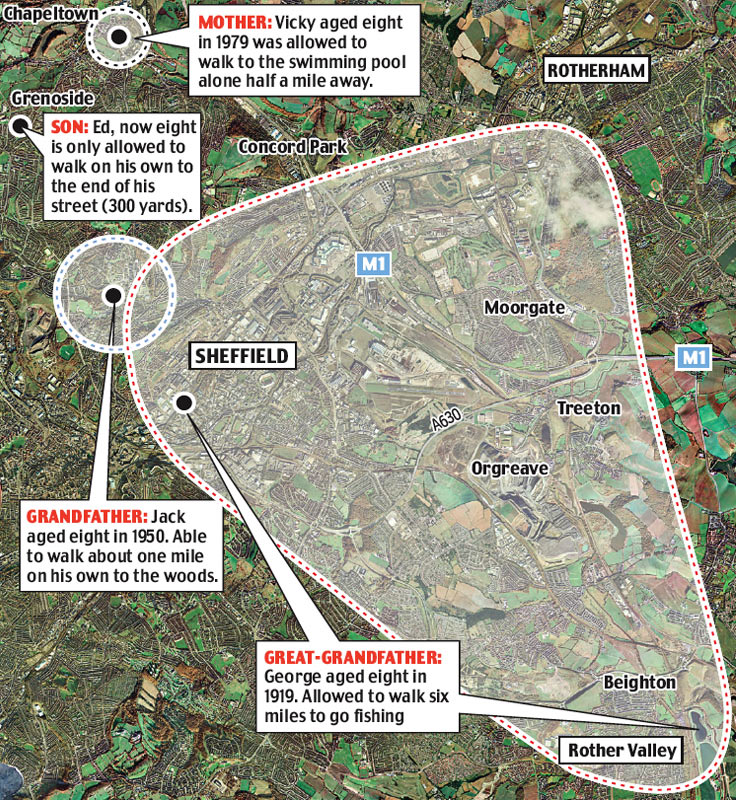

It’s a commonplace assertion that children today have less unscheduled, unsupervised opportunities for play and exploration, and parents have been indoctrinated into the belief that the world has become a much more dangerous place and their kids need 24/7 protection from those myriad dangers. “Helicopter” parenting is a rational response to this indoctrination, but it comes with costs to the growth and maturity of the next generation. More than a decade ago, I posted this graphic showing how each generation has been more protective of their own children than their parents had been for them:

The problem has been getting worse over time, as Rob Creasy and Fiona Corby describe:

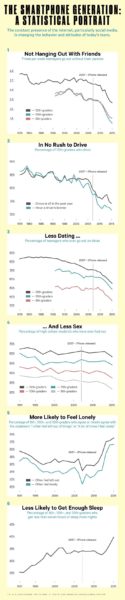

Children growing up in the UK are said to be some of the unhappiest in the industrialised world. The UK now has the highest rates of self harm in Europe. And the NSPCC’s ChildLine Annual Review lists it as one of the top reasons why children contact the charity.

Children’s mental health has becomes one of British society’s most pressing issues. A recent report from the Prince’s Trust highlights how increasing numbers of children and young people are unhappy with their lives, sometimes with tragic consequences.

This is a generation of young people that has been labelled as “snowflakes” – unable to handle stress and more prone to taking offence. They are also said to have less psychological resilience than previous generations. And are thought to be too emotionally vulnerable to cope with views that challenge their own.

[…]

Children’s lives are being stifled. No longer are children able to spend time with friends unsupervised, explore their community or hang around in groups without being viewed with suspicion. Very little unsupervised play and activity occurs for children in public spaces or even in homes – and a children’s spare time is often eaten up by homework or organised activity.

This is further impacted by the way children are taught in schools and how pressure to succeed has led to a taming of education. But if children are never challenged, if they don’t ever experience adversity, or face risks then it is not surprising they will lack resilience.