World War Two

Published 13 February 2025November 1930 sees Germany caught between political instability and international disputes. Brüning fights to pass his controversial budget while Germany’s push for global disarmament meets French resistance and Nazi outrage. Meanwhile, Hitler restructures the SA and SS, student duels make headlines, and Berlin’s police chief is attacked in court.

(more…)

February 14, 2025

Disarmament Talks, Budget Battles, and Student Duels – Nov 1930

December 28, 2022

What we still don’t know about historical European swordfighting

I was for many years a member of the SCA partly for the attraction of the historical period and partly for the swordfighting. The Society developed a (mostly) safe simulation of (some) medieval combat styles and later introduced (some) renaissance rapier combat as well (initially borrowing equipment standards from modern sport fencing). Around the time the SCA began to consider expanding from high medieval sword-and-shield styles, separate organizations in Europe and the United States sprang up to be more consciously historical in how they recreated historical blade combat, these groups are often collectively referred to as Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) or Western Martial Arts (WMA). The foundation documents for HEMA and other historical combat enthusiasts are the various surviving manuals of swordmasters and fencing school owners which cover a kaleidoscope of weapons, techniques, advice, and how-to illustrations … some of which appear to be physically impossible for ordinary human beings:

The ultimate experts in medieval sword fighting were the “fight masters” – elite athletes who trained their disciples in the subtle arts of close combat. The most highly renowned were almost as famous as the knights they trained, and many of the techniques they used were ancient, dating back hundreds of years in a continuous tradition.

Little is known about these rare talents, but the scraps of information that have survived are full of intrigue. Hans Talhoffer, a German fencing master with curly hair, impressive sideburns and a penchant for tight body suits, had a particularly chequered past. In 1434, he was accused of murdering a man and admitted abducting him in the Austrian city of Salzburg.

Fight masters worked with a grisly assortment of deadly weapons. The majority of training was dedicated to fencing with the longsword, or the sword and buckler (a style of combat involving holding a sword in one hand, and a small shield in the other). However, they also taught how to wield daggers, poleaxes, shields, and even how to fight with nothing at all, or just a bag of rocks (more on this later).

It’s thought that some fight masters were organised into brotherhoods, such as the Fellowship of Liechtenauer – a society of around 18 men who trained under the shadowy grandmaster Johannes Lichtenauer in the 15th Century. Though details about the almost-legendary figure himself have remained elusive, it’s thought he led an itinerant life, travelling across borders to train a handful of select proteges and learn new fencing secrets.

Other fight masters stayed closer to home – hired by dukes, archbishops and other assorted nobles to train themselves and their guards. A number even set up their own “fight schools”, where they gathered less wealthy students for regular weekly sessions.

[…]

For all their beauty, the hand-drawn works could also be decidedly bloodthirsty. In Talhoffer’s 1467 manual, neat sequences of moves that look almost like dancing end abruptly with swords through eye-sockets, violent impalings, and casual instructions to beat the opponent to death. Some signature techniques even have names – chilling titles like the “wrath-hew”, “crumpler”, “twain hangings”, “skuller” and “four openings”.

Despite passing through countless generations of owners, and – in some cases – centuries of graffiti, burns, theft, and mysterious periods of vanishment from the historical record, a surprising number survive today. This includes at least 80 codexes from German-speaking regions alone.

Impossible moves and missing clues

But there’s a problem. Many of the techniques in combat manuals, also known as “fechtbücher“, are convoluted, vague, and cryptic. Despite the large corpus of remaining books, they often offer surprisingly little insight into what the fight master is trying to convey.

“It’s famously difficult to take these static unmoving woodcut images, and determine the dynamic action of combat,” says Scott Nokes, “This has been a topic of debate, research and experimentation for generations.”

On some occasions these manuals seem to depict contortions of the body that are physically impossible, while those that attempt to convey moves in three dimensions sometimes give combatants extra arms and legs that were added in by accident. Others contain instructions that are frustratingly opaque – sometimes depicting actions that don’t seem to work, or building upon enigmatic moves that have long-since been lost.

Oddly, the text is often written as poetry, rather than prose – and a few authors even made it hard to interpret their works on purpose.

Lichtenauer recorded his instructions in obscure verses which remain almost incomprehensible today – one expert has gone so far as to call them “gibberish”. According to a contemporary fight master he trained, the grandmaster wrote in “secret words” to prevent them from being intelligible to anyone who didn’t value his art highly enough.

Even when it is possible to decipher what a combat manual is describing or demonstrating, some experts suspect that crucial contextual information is always missing.

December 1, 2022

QotD: Movie swordfighting

I was reminded, earlier today, that one of the interesting side effects of knowing something about hand-to-hand and contact-weapons-based martial arts makes a big difference in how you see movies.

Most people don’t have that knowledge. So today I’m going to write about the quality of sword choreography in movies, and how that has changed over time, from the point of view of someone who is an experienced multi-style martial artist in both sword and empty hand. I think this illuminates a larger story about the place of martial arts in popular Western culture.

The first thing to know is this: with only rare exceptions, any Western swordfighting you see in older movies is going to be seriously anachronistic. It’s almost all derived from French high-line fencing, which is also the basis for Olympic sport fencing. French high-line is a very late style, not actually fully developed until early 1800s, that is adapted for very light thrusting weapons. These are not at all typical of the swords in use over most of recorded history.

In particular, the real-life inspirations for the Three Musketeers, in the 1620s, didn’t fight anything like their movie versions. They used rapiers – thrusting swords – all right, but their weapons were quite a bit longer and heavier than a 19th-century smallsword. Correspondingly, the tempo of a fight had to be slower, with more pauses as the fighters watched for an opening (a weakness in stance or balance, or a momentary loss of concentration). Normal guard position was lower and covered more of center line, not the point-it-straight-at-you of high line. You find all this out pretty quickly if you actually train with these weapons.

The thing is, real Three Musketeers fencing is less flashy and dramatic-looking than French high-line. So for decades there was never any real incentive for moviemakers to do the authentic thing. Even if there had been, audiences conditioned by those decades of of high-line would have thought it looked wrong!

Eric S. Raymond, “A martial artist looks at swordfighting in the movies”, Armed and Dangerous, 2019-01-13.

August 4, 2022

QotD: Errol Flynn versus Basil Rathbone in the 1938 Adventures of Robin Hood

A lot of swordfighting in medieval-period movies is even less appropriate if you know what the affordances of period weapons were. The classic Errol Flynn vs. Basil Rathbone duel scene from the 1938 Adventures of Robin Hood, for example. They’re using light versions of medieval swords that are reasonably period for the late 1100s, but the footwork and stances and tempo are all French high line, albeit disguised with a bunch of stagey slashing moves. And Rathbone gets finished off with an epée (smallsword) thrust executed in perfect form.

It was perfect form because back in those days acting schools taught their students how to fence. It was considered good for strength, grace, and deportment; besides, one might need it for the odd Shakespeare production. French high-line because in the U.S. and Europe that was what there were instructors for; today’s Western sword revival was still most of a century in the future.

This scene exemplifies why I find the ubiquitousness of French high-line so annoying. It’s because that form, adapted for light thrusting weapons, produces a movement language that doesn’t fit heavier weapons designed to slash and chop as well as thrust. If you’re looking with a swordsman’s eye you can see this in that Robin Hood fight. Yes, the choreographer can paste in big sweeping cuts, and they did, but they look too much like exactly what they are – theatrical flourishes disconnected from the part that is actually fighting technique. When Flynn finishes with his genuine fencer’s lunge (not a period move) he looks both competent and relieved, as though he’s glad to be done with the flummery that preceded it.

At least Flynn and Rathbone had some idea what they were doing. After their time teaching actors to fence went out of fashion and the quality of cinematic sword choreography nosedived. The fights during the brief vogue for sword-and-sandal movies, 1958 to 1965 or so, were particularly awful. Not quite as bad, but all too representative, was the 1973 Three Musketeers: The Queen’s Diamonds, a gigantic snoozefest populated with slapdash, perfunctory swordfights that were on the whole so devoid of interest and authenticity that even liberal display of Raquel Welch’s figure could not salvage the mess. When matters began to improve again in the 1980s the impetus came from Asian martial-arts movies.

Eric S. Raymond, “A martial artist looks at swordfighting in the movies”, Armed and Dangerous, 2019-01-13.

October 9, 2020

Olympic-style fencing: a YouTuber versus a professional – you won’t be shocked by what happened next

Lindybeige

Published 2 Jul 2020You see me here take on the top fencer in Guatemala in his gym. We are using epees, and one of us is using skill while the other shows what can be achieved with controlled panic.

Some may note it odd that at no point do I used my far-famed long and supple legs for a lunge. As I explain near the end, I had food poisoning, and had spent a large part of that day on the loo. A lunge executed with gusto would have been unwise.

Support me on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/Lindybeige

Many thanks to Inguat (the Guatemalan tourist board) for inviting me over.

Some links to Guatemalan websites:

https://visitguatemala.com

https://www.nomadawaycorp.com/adventure

http://mayatrek.visitguatemala.com/ab…Cameraman: Jeremy Lawrence (https://www.futtfuttfutt.com)

Buy the music – the music played at the end of my videos is now available here: https://lindybeige.bandcamp.com/track…

Buy tat (merch):

https://outloudmerch.com/collections/lindybeigeLindybeige: a channel of archaeology, ancient and medieval warfare, rants, swing dance, travelogues, evolution, and whatever else occurs to me to make.

▼ Follow me…

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Lindybeige I may have some drivel to contribute to the Twittersphere, plus you get notice of uploads.

My website:

http://www.LloydianAspects.co.uk

March 20, 2019

Over-Analyzing The Iconic Duel in The Princess Bride: How Accurate is It?

Skallagrim

Published on 16 Feb 2019Support My Channel! Download Free

Vikings War Of Clans Here

➤ IOS: https://bit.ly/2TQVxjY

➤ Android: https://bit.ly/2TMlMbm

And Get 200Gold, And a ⛨ Protective Shield for FREE

Have you ever wondered what Inigo Montoya and Westley chatter about while dueling with swords? What is Bonetti’s Defense? Does Thibault really cancel out Capo Ferro? And how realistic is the fighting overall?

You’ll find out in this video.

From the comments:

Skallagrim

2 days agoYes, you caught me… Should have said Thibault’s treatise was published in 1630. He did not write it after his death…

Although that would be pretty badass. Imagine you’re so dedicated to the art of fencing that you become a lich just to finish your work.

February 15, 2019

QotD: The swordfight from The Princess Bride

I cannot, however, pass by that period without noting one moment of excellence; The Princess Bride (1987). Yes, this is classic stagy Hollywood high-line, consciously referring back to precedents including the Flynn/Rathbone scene from fifty years earlier – but in this context there’s no sense of anachronism because the movie is so cheerfully vague about its time period. The swords are basket-hilted rapiers in an ornate Italo-French style that could date from 1550 to their last gasp in the Napoleonic Wars. The actors use them with joy and vigor – Elwes and Patinkin learned to fence (both left- and right-handed) for the film and other than the somersaults their fight scene was entirely them, not stunt doubles. It’s a bright, lovely contrast with the awfulness of most Hollywood sword choreography of the time and, I think, part of the reason the movie has become a cult classic.

Eric S. Raymond, “A martial artist looks at swordfighting in the movies”, Armed and Dangerous, 2019-01-13.

January 11, 2015

Sport fencing no longer teaches swordsmanship – HEMA does

I’ve given (shorter and less detailed) variants of this argument many times. I agree with pretty much everything he says here:

I started to learn sport fencing (or “Olympic-style”) as a child in England. My parents were both long-time fencers, so one of my earliest memories is from around age three or four, standing in our tiny backyard, trying to learn basic parries with a foil. My father had been experimenting with bringing in a form of rapier and dagger at his fencing club, but there were no reasonable simulation rapiers on the market in those days, so the default equipment was a sabre and a broken-off foil as a dagger. Let’s just say that the idea was very popular in the club, but the implementation failed to energize many because the equipment wasn’t all that close to representative: the weapons were far too light and any attempt to use historical methods was doomed because the swordplay lacked the momentum of full-sized/full-weight rapiers. Things that worked fantastically well with the modern weapons would get you deader than dead using proper historical weaponry.

I gave up sport fencing as a hobby around the time that orthopedic grips and electrical scoring came in … as the man says in the video above, it became too much like electric tag and too little like historical swordplay. Instead of being relatively straight or slightly curved, orthopedic grips looked rather like what would happen if you squeezed a ball of soft coloured clay in your hand. I hated the feel of them, but other fencers at my club loved them. The electrical scoring system of the day required each fencer to wear an over-jacket covering the valid target area, and trail along a cable attached to the back of the over-jacket. The matching foil had a socket on the inside of the guard for attaching the cable to the other side of the scoring circuit. When the tip of the foil hit the conductive surface of the opponent’s over-jacket, the circuit was completed and a point would be scored.

I gave up sport fencing as a hobby around the time that orthopedic grips and electrical scoring came in … as the man says in the video above, it became too much like electric tag and too little like historical swordplay. Instead of being relatively straight or slightly curved, orthopedic grips looked rather like what would happen if you squeezed a ball of soft coloured clay in your hand. I hated the feel of them, but other fencers at my club loved them. The electrical scoring system of the day required each fencer to wear an over-jacket covering the valid target area, and trail along a cable attached to the back of the over-jacket. The matching foil had a socket on the inside of the guard for attaching the cable to the other side of the scoring circuit. When the tip of the foil hit the conductive surface of the opponent’s over-jacket, the circuit was completed and a point would be scored.

It was clumsy and awkward, and didn’t feel much like a swordfight. I pretty much gave up the foil and switched to sabre, for they didn’t yet have a working electric system for sabre fighting, so you didn’t need to get hooked up to the machine just to fight a bout. When they got that little problem fixed, I’d already given up sport fencing.

The SCA finally adopted rapier fencing and the Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) movement arrived well after I’d given up sport fencing, and I’ve enjoyed the SCA’s rapier combat quite a bit (although I tend to go inactive for a year or two, then go back for a similar length of time … I may not improve that way, but it’s still fun). More serious fencers and those interested in a wider range of styles end up joining HEMA organizations, where I’m told they take things much more seriously. I can’t say from personal experience, as I only visited a Toronto HEMA group once and most of the members there were working on much earlier styles of swordplay (like longsword) than I was interested in at the time.

H/T to Brendan McKenna for the link to the video.

December 21, 2014

The first historical European martial arts tournament

Aaron Miedema shared a link to this story about the first known tournament for historical European martial arts:

If I asked you when was the first historical European Martial Arts tournament what would you say? 1997? 2003?

Not even close.

How about where? America? Great Britain? Germany? France?

No, none of the above.

What if I told you that the earliest known tournament took place in a region of the globe which we probably don’t hear enough about, but which surely deserves to be known across the HEMA community: Quebec.

Yes. The first ever tournament took place on the island of Montreal in… 1889. Who was heading this tournament? Perhaps Alfred Hutton on a trip in Canada? Or how about one of those French guys from the Olympics? No, it was another HEMA pioneer. One which is unfortunately unknown to us because he did not leave us any manual, but an interesting figure all the same: David Legault.

[…]

Legault came back to Montreal around 1882. There were very few qualified fencing instructors in town at that time, and the art was going through a revival. His friends then encouraged David to open up a fencing salle in the former Institut Canadien, a learned French Canadian society which regularly drew the wrath of the church. There he will teach not only swordsmanship but also boxing, savate, wrestling, great stick and gymnastics. He will try to introduce the model inside Quebec schools, with more or less success, but his regular classes will grow in popularity and Legault will decide to change the nature of his club which will become known as the Guard of the Archiepiscopal Palace. This group acted as an honorary guard to the Catholic archbishop of Montreal as well as a sort of militia to prepare men for military service. Several similar groups will be created across the province, all of them teaching fencing. Volunteering in the Canadian army and various official militia units which were mostly English speaking was not very popular with French Canadians, and many turned toward these groups instead.

September 29, 2014

When I started fencing, I was told there was no math…

John Turner sent me a link to this short article in Slate‘s “The Vault” column, discussing the mathematical side of fencing:

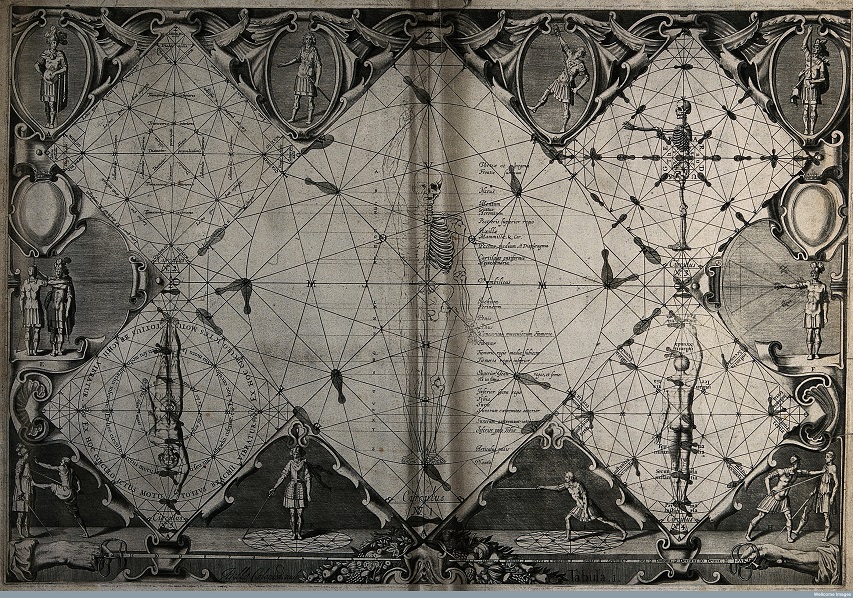

Girard Thibault’s Académie de l’Espée (1628) puts the art of wielding the sword on mathematical foundations. For Thibault, a Dutch fencing master from the early seventeenth century, geometrical rules determined each and every aspect of fencing. For example, the length of your rapier’s blade should never exceed the distance between your feet and the navel, and your movements in a fight should always be along the lines of a circle whose diameter is equal to your height.

The rest of his manual, geared towards gentlemanly readers who took up fencing as a noble sport, is filled with similar geometrical arguments about the choreography of swordsmanship. Thibault’s work belongs to the same tradition that produced Leonardo’s renowned Vitruvian Man.

May 4, 2014

Three Japanese fencers and 50 opponents

H/T to Tim Harford for the link.

February 2, 2013

December 22, 2010

Bad Boy Fencing Star Implicated in Yet Another Jewel Heist

July 22, 2010

Swordplay is hard work

Peter Saltsman visits Toronto’s Academy of European Medieval Martial Arts (AEMMA) and finds that there’s not much “play” when you’re just starting to learn how to wield a sword:

I was hoping this courageous group of historians and hobbyists could teach me to fight like they do in movies such as Robin Hood, Macbeth or the new Pillars of the Earth series. In the movies, it looks so easy. The sword fights I know are the perfect harmony of choreographed bravado, hyperbolic grunting and dramatic pauses for someone to say “My name is Inigo Montoya. You killed my father. Prepare to die.”

To the disappointment of my eight-year-old self, real medieval combat is nothing like that.

“They’re not really trying to hit each other,” says Cal Rekuta, a Senior Free Scholar at AEMMA, of cinematic battles. “Stage fighting is the art of looking dangerous. We’re actually studying how it was dangerous.”

I was in over my head. When a man dressed in a full suit of chain-mail armour — armour he weaved himself — talks about danger, he probably means it.

I visited AEMMA once, several years ago. It was quite an enjoyable experience, but I’m more interested in later-period swordwork than most of their membership at that time.

July 3, 2010

More swordwork today

As I expected, the larger turnout of fencers yesterday prevented me from repeating as high a finish as the last two tournaments, but there’s more happening today. The morning tournament was a double-elimination, but the afternoon was a much briefer single-elimination. At least with double-elimination, you can recover from a mistake (theoretically).