Published on 17 Jul 2017

Check out the WW1 Centennial Podcast: http://bit.ly/WW1CCPodcast

Tunnel and mining warfare was an important part of World War 1, especially on the Western Front and to a lesser, but still deadly, degree on the Italian Front. The dangers for the tunnelers were immense. And the destruction they caused with explosions was too.

July 18, 2017

Tunnel Warfare During World War 1 I THE GREAT WAR Special

July 9, 2017

Why Are I-Beams Shaped Like An I?

Published on 8 Dec 2016

Thank you to my patreon supporters: Adam Flohr, darth patron, Zoltan Gramantik, Josh Levent, Henning Basma, Karl Andersson, Mark Govea

February 14, 2017

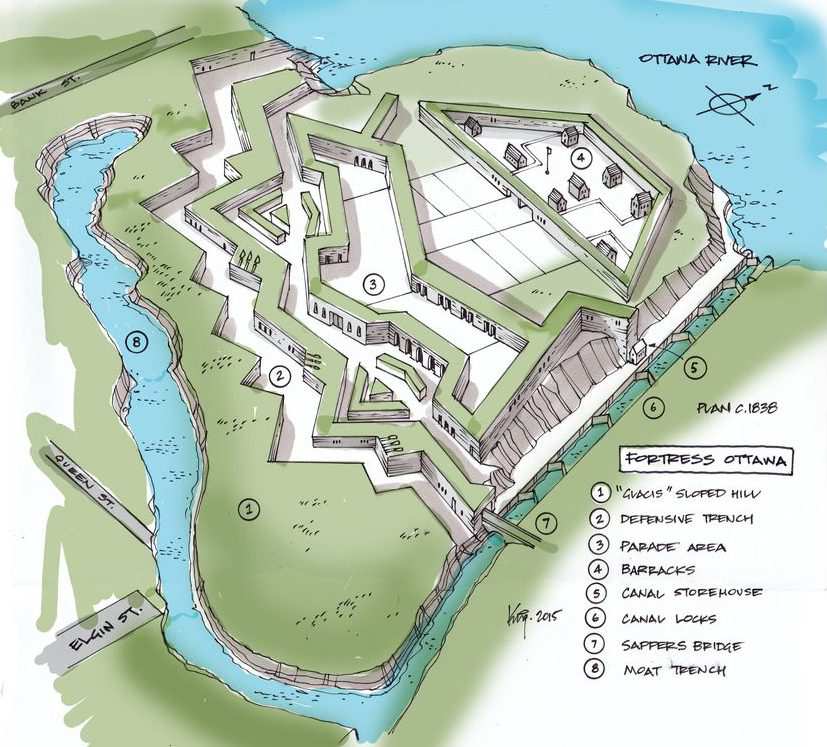

Fortress Ottawa, a post-War of 1812 alternative use for Parliament Hill

Colby Cosh linked to this Ottawa Citizen article by Andrew King:

Mapped out with defensive moats, trenches and cannon placements, Bytown’s sprawling stone fortification on the hill was a typical 19th century “star fort,” similar to Fort George in Halifax, also known as Citadel Hill, and the Citadelle de Québec in Quebec City. The “star fort” layout style evolved during the era of gunpowder and cannons and was perfected by Sebastien Le Prestre de Vauban, a French engineer who studied 16th century forts designed by the Knights of Malta. A star fort built by the order with trenches and angled walls withstood a month-long siege by the Ottoman Empire. This layout remained the standard in fort design until the 20th century.

Ottawa’s planned fortress would have also integrated a water-filled moat trench to the south, where Laurier Street is now, to impede an attack. On the northern side, the natural limestone cliffs along the Ottawa River would have served as a defensive measure. Access and resupply points were at the canal near the Sappers Bridge, and a zigzagging trench with six-metre-high stone walls would have run parallel to Queen Street. Parliament Hill, with its gently sloping banks to the south, was called a “glacis” positioned in front of the main trench so that the walls were almost totally hidden from horizontal artillery attack, preventing point-blank enemy fire.

After the rebellions were quashed and the threat of an attack from the United States fizzled out by the mid-1850s, Canada abandoned plans to fortify Bytown.

In 1856, the Rideau Canal system was relinquished to civilian control, and three years later Bytown was selected as the capital of the Province of Canada. The grand plans for Ottawa’s massive stone fortress were shelved and the area that would have been Citadel Hill became the scene of a different kind of battle, that of politics.

November 13, 2016

QotD: Don’t call it software engineering

The #gotofail episode will become a text book example of not just poor attention to detail, but moreover, the importance of disciplined logic, rigor, elegance, and fundamental coding theory.

A still deeper lesson in all this is the fragility of software. Prof Arie van Deursen nicely describes the iOS7 routine as “brittle”. I want to suggest that all software is tragically fragile. It takes just one line of silly code to bring security to its knees. The sheer non-linearity of software — the ability for one line of software anywhere in a hundred million lines to have unbounded impact on the rest of the system — is what separates development from conventional engineering practice. Software doesn’t obey the laws of physics. No non-trivial software can ever be fully tested, and we have gone too far for the software we live with to be comprehensively proof read. We have yet to build the sorts of software tools and best practice and habits that would merit the title “engineering”.

I’d like to close with a philosophical musing that might have appealed to my old mentors at Telectronics. Post-modernists today can rejoice that the real world has come to pivot precariously on pure text. It is weird and wonderful that technicians are arguing about the layout of source code — as if they are poetry critics.

We have come to depend daily on great obscure texts, drafted not by people we can truthfully call “engineers” but by a largely anarchic community we would be better of calling playwrights.

Stephan Wilson, “gotofail and a defence of purists”, Lockstep, 2014-02-26.

March 18, 2016

Explosives – WW1 Uncut – BBC

Published on 31 Jul 2014

The use of massive bombs and charges by the Royal Engineers was crucial during the war. See slow motion footage of them using explosive devices such as the Bangalore Torpedo today.

November 16, 2015

“Skunk Works” founder Kelly Johnson’s Rules Of Management

Tyler Rogoway recounts the set of formal and informal rules Kelly Johnson used while running the famous “Skunk Works”:

Clarence “Kelly” Johnson is the Babe Ruth of aerospace design. Aircraft programs under Johnson were so cutting edge and historically influential, and his cult of personality and management strategy so effective, that he and Lockheed’s Skunk Works (which he also founded) are forever enshrined in mankind’s technological hall of fame.

[…]

Kelly’s Rules

1. The Skunk Works manager must be delegated near complete control of his program in all aspects. He should report to a division president or higher.

2. Strong but small project offices must be provided both by the military and industry.

3. The number of people having any connection with the project must be restricted in an almost vicious manner. Use a small number of good people (10% to 25% compared to the so-called normal systems).

4. A very simple drawing and drawing release system with great flexibility for making changes must be provided.

5. There must be a minimum number of reports required, but important work must be recorded thoroughly.

6. There must be a monthly cost review covering not only what has been spent and committed but also projected costs to the conclusion of the program.

7. The contractor must be delegated and must assume more than normal responsibility to get good vendor bids for subcontract on the project. Commercial bid procedures are often better than military ones.

8. The inspection system as currently used by the Skunk Works, which has been approved by both the Air Force and Navy, meets the intent of existing military requirements and should be used on new projects. Push more basic inspection responsibility back to subcontractors and vendors. Don’t duplicate so much inspection.

9. The contractor must be delegated the authority to test his final product in flight. He can and must test it in the initial stages. If he doesn’t, he rapidly loses his competency to design other vehicles.

10. The specifications applying to the hardware, including rationale for each point, must be agreed upon well in advance of contracting.

11. Funding a program must be timely so that the contractor doesn’t have to keep running to the bank to support government projects.

12. There must be mutual trust between the military project organization and the contractor, and there must be very close cooperation and liaison on a day-to-day basis. This cuts down misunderstanding and correspondence to an absolute minimum.

13. Access by outsiders to the project and its personnel must be strictly controlled by appropriate security measures.

14. Because only a few people will be used in engineering and most other areas, ways must be provided to reward good performance by pay not based on the number of personnel supervised.

Kelly also had a unofficial 15th, 16th, and 17th rules, which he is known to have stated repeatedly to his subordinates:

15. Never do business with the Navy!

16. No reports longer than 20 pages or meetings with more than 15 people.

17. If it looks ugly, it will fly the same.

It is amazing to think that one man did so much to advance mankind’s aerospace capability. Even his few dead-ends and failures had key technologies that would lead to wins or lessons learned down the road.

H/T to @NavyLookout for the link.

October 5, 2015

Why are women under-represented in STEM?

Yet another link I meant to post a while back, but it got lost in the shuffle:

Readers of the higher education press and literature may be forgiven for supposing that there is more research on why there are not more women in STEM fields than there is actual research in the STEM fields themselves. The latest addition to this growing pile of studies appeared a few months ago in Science, and now Science has just published a new study refuting the earlier one.

In the earlier study, “Expectations of Brilliance Underlie Gender Distributions Across Academic Disciplines,” Sarah-Jane Leslie, a philosophy professor at Princeton, and several co-authors surveyed more than 1800 academics across 30 disciplines — graduate students, postdocs, junior and senior faculty — to determine the extent of their agreement with such statements as, “Being a top scholar of [your field] requires a special aptitude that just can’t be taught” and whether “men are more often suited than women to do high-level work in [your field.]”

Fields that believe innate brilliance is essential to high success, such as physics and philosophy, have a significantly smaller proportion of women than fields that don’t, such as Psychology and Molecular Biology.

[…]

What Ginther and Kahn found, in short, is that it was not “expectations of brilliance” that predicted the representation of women in various fields “but mathematical ability, especially relative to verbal ability…. While field-specific ability beliefs were negatively correlated with the percentage of female Ph.D.s in a field, this correlation is likely explained by women being less likely than men to study these math-intensive fields.”

Ginther’s and Kahn’s argument was anticipated and developed even beyond theirs by psychiatrist Scott Alexander in a brilliant long entry on his widely read Slate Codex blog, “Perceptions of Required Ability Act As A Proxy For Actual Required Ability In Explaining The Gender Gap.” His criticism of Leslie et al. is even more devastating:

Imagine a study with the following methodology. You survey a bunch of people to get their perceptions of who is a smoker (“97% of his close friends agree Bob smokes.”) Then you correlate those numbers with who gets lung cancer. Your statistics program lights up like a Christmas tree with a bunch of super-strong correlations. You conclude, “Perception of being a smoker causes lung cancer,” and make up a theory about how negative stereotypes of smokers cause stress which depresses the immune system. The media reports that as “Smoking Doesn’t Cause Cancer, Stereotypes Do.”

This is the basic principle behind Leslie et al.

Like Ginther and Kahn, who did not cite his work, Alexander disaggregated the quantitative from the verbal GRE scores and found that the correlation between quantitative GRE score and percent of women in a discipline to be “among the strongest correlations I have ever seen in social science data. It is much larger than Leslie et al’s correlation with perceived innate ability. Alexander’s piece, and in fact his entire blog, should be required reading.

October 3, 2015

Great Britons: Isambard Kingdom Brunel Hosted by Jeremy Clarkson – BBC Documentary

Published on 16 Jul 2014

Jeremy Clarkson follows in the footsteps of the great engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel whose designs for bridges, railways, steamships, docks and buildings revolutionised modern engineering. But his boldness and determination to succeed often led him to repeatedly risk his own life. Jeremy Clarkson, discovers for himself just how terrifying that was.

H/T to Ghost of a Flea for the link.

September 3, 2015

How Buildings Learn – Stewart Brand – 6 of 6 – “Shearing Layers”

Published on 10 Jun 2012

This six-part, three-hour, BBC TV series aired in 1997. I presented and co-wrote the series; it was directed by James Muncie, with music by Brian Eno.

The series was based on my 1994 book, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: What Happens After They’re Built. The book is still selling well and is used as a text in some college courses. Most of the 27 reviews on Amazon treat it as a book about system and software design, which tells me that architects are not as alert as computer people. But I knew that; that’s part of why I wrote the book.

Anybody is welcome to use anything from this series in any way they like. Please don’t bug me with requests for permission. Hack away. Do credit the BBC, who put considerable time and talent into the project.

Historic note: this was one of the first television productions made entirely in digital — shot digital, edited digital. The project wound up with not enough money, so digital was the workaround. The camera was so small that we seldom had to ask permission to shoot; everybody thought we were tourists. No film or sound crew. Everything technical on site was done by editors, writers, directors. That’s why the sound is a little sketchy, but there’s also some direct perception in the filming that is unusual.

August 26, 2015

How Buildings Learn – Stewart Brand – 5 of 6 – “The Romance of Maintenance”

Published on 10 Jun 2012

This six-part, three-hour, BBC TV series aired in 1997. I presented and co-wrote the series; it was directed by James Muncie, with music by Brian Eno.

The series was based on my 1994 book, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: What Happens After They’re Built. The book is still selling well and is used as a text in some college courses. Most of the 27 reviews on Amazon treat it as a book about system and software design, which tells me that architects are not as alert as computer people. But I knew that; that’s part of why I wrote the book.

Anybody is welcome to use anything from this series in any way they like. Please don’t bug me with requests for permission. Hack away. Do credit the BBC, who put considerable time and talent into the project.

Historic note: this was one of the first television productions made entirely in digital — shot digital, edited digital. The project wound up with not enough money, so digital was the workaround. The camera was so small that we seldom had to ask permission to shoot; everybody thought we were tourists. No film or sound crew. Everything technical on site was done by editors, writers, directors. That’s why the sound is a little sketchy, but there’s also some direct perception in the filming that is unusual.

August 20, 2015

How Buildings Learn – Stewart Brand – 4 of 6 – “Unreal Estate”

Published on 10 Jun 2012

This six-part, three-hour, BBC TV series aired in 1997. I presented and co-wrote the series; it was directed by James Muncie, with music by Brian Eno.The series was based on my 1994 book, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: What Happens After They’re Built. The book is still selling well and is used as a text in some college courses. Most of the 27 reviews on Amazon treat it as a book about system and software design, which tells me that architects are not as alert as computer people. But I knew that; that’s part of why I wrote the book.

Anybody is welcome to use anything from this series in any way they like. Please don’t bug me with requests for permission. Hack away. Do credit the BBC, who put considerable time and talent into the project.

Historic note: this was one of the first television productions made entirely in digital— shot digital, edited digital. The project wound up with not enough money, so digital was the workaround. The camera was so small that we seldom had to ask permission to shoot; everybody thought we were tourists. No film or sound crew. Everything technical on site was done by editors, writers, directors. That’s why the sound is a little sketchy, but there’s also some direct perception in the filming that is unusual.

August 12, 2015

How Buildings Learn – Stewart Brand – 3 of 6 – “Built for Change”

Published on 10 Jun 2012

This six-part, three-hour, BBC TV series aired in 1997. I presented and co-wrote the series; it was directed by James Muncie, with music by Brian Eno.

The series was based on my 1994 book, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: What Happens After They’re Built. The book is still selling well and is used as a text in some college courses. Most of the 27 reviews on Amazon treat it as a book about system and software design, which tells me that architects are not as alert as computer people. But I knew that; that’s part of why I wrote the book.

Anybody is welcome to use anything from this series in any way they like. Please don’t bug me with requests for permission. Hack away. Do credit the BBC, who put considerable time and talent into the project.

Historic note: this was one of the first television productions made entirely in digital — shot digital, edited digital. The project wound up with not enough money, so digital was the workaround. The camera was so small that we seldom had to ask permission to shoot; everybody thought we were tourists. No film or sound crew. Everything technical on site was done by editors, writers, directors. That’s why the sound is a little sketchy, but there’s also some direct perception in the filming that is unusual.

August 5, 2015

How Buildings Learn – Stewart Brand – 2 of 6 – “The Low Road”

Published on 10 Jun 2012

This six-part, three-hour, BBC TV series aired in 1997. I presented and co-wrote the series; it was directed by James Muncie, with music by Brian Eno.

The series was based on my 1994 book, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: What Happens After They’re Built. The book is still selling well and is used as a text in some college courses. Most of the 27 reviews on Amazon treat it as a book about system and software design, which tells me that architects are not as alert as computer people. But I knew that; that’s part of why I wrote the book.

Anybody is welcome to use anything from this series in any way they like. Please don’t bug me with requests for permission. Hack away. Do credit the BBC, who put considerable time and talent into the project.

Historic note: this was one of the first television productions made entirely in digital — shot digital, edited digital. The project wound up with not enough money, so digital was the workaround. The camera was so small that we seldom had to ask permission to shoot; everybody thought we were tourists. No film or sound crew. Everything technical on site was done by editors, writers, directors. That’s why the sound is a little sketchy, but there’s also some direct perception in the filming that is unusual.

July 29, 2015

How Buildings Learn – Stewart Brand – 1 of 6 – “Flow”

Published on 10 Jun 2012

This six-part, three-hour, BBC TV series aired in 1997. I presented and co-wrote the series; it was directed by James Muncie, with music by Brian Eno.

The series was based on my 1994 book, HOW BUILDINGS LEARN: What Happens After They’re Built. The book is still selling well and is used as a text in some college courses. Most of the 27 reviews on Amazon treat it as a book about system and software design, which tells me that architects are not as alert as computer people. But I knew that; that’s part of why I wrote the book.

Anybody is welcome to use anything from this series in any way they like. Please don’t bug me with requests for permission. Hack away. Do credit the BBC, who put considerable time and talent into the project.

Historic note: this was one of the first television productions made entirely in digital — shot digital, edited digital. The project wound up with not enough money, so digital was the workaround. The camera was so small that we seldom had to ask permission to shoot; everybody thought we were tourists. No film or sound crew. Everything technical on site was done by editors, writers, directors. That’s why the sound is a little sketchy, but there’s also some direct perception in the filming that is unusual.

May 21, 2015

The Brunel Museum

Brid-Aine Parnell talks about the Brunels — father, son, and grandson — and their impact on Britain during the industrial revolution:

When you mention Brunel to most people, they think of the one with the funny name – Isambard Kingdom Brunel. A few folks will know that his father Marc Isambard Brunel was the first famous engineering Brunel, but not many will know that Isambard’s own son, Henry Marc Brunel, was also an engineer and finished some of Isambard’s projects after his death.

Between the three of them, the Brunels created landmarks all over the UK; perhaps most famously the Clifton Suspension Bridge, which spans the Avon Gorge, linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in Somerset.

That bridge, which Isambard Kingdom Brunel designed and often called his “first child,” wasn’t actually completed until after his death and only came about at all because Isambard was nearly drowned in an accident at the massive project he was working on in London with his father: the Thames Tunnel.

It is this masterpiece of engineering, which invented new methods of tunnelling underground and is why the Brunels are credited with creating underground transportation – and by extension, the modern city itself – that you see if you go along to the Brunel Museum in Rotherhithe, London.

The museum itself is in Marc Brunel’s Engine House, built in 1842, the year before the Thames Tunnel was opened, for the engines that pumped to keep the Tunnel dry. The small exhibition tells the story of the design and construction of the 396-metre-long tunnel, the first to have been successfully built underneath a navigable river. The display panels also detail the innovative tunnelling shield technique invented by Marc and Isambard that’s still used to build tunnels today, although these days it’s machines doing the hard work instead of men. Back then, labourers would spent two hours at a time digging, often while also being gassed and showered with shit.

The River Thames at that time was the sewer of London and the tunnel was constantly waterlogged, leading to a build up of effluent and methane gas. The result was that not only would miners pass out from the gas – even if they didn’t, men who re-surfaced were left senseless after their two-hour shift – but there were also explosions as the gas was set alight by the miners’ candles.

Although it’s a tidy and well-kept little exhibition, it is not really why you come to the museum. You come for the underground chamber below, which was only opened up to the public in 2010 after 150 years of being closed off by the London transportation system. This is the Grand Entrance Hall to the Thames Tunnel, used in Brunel’s day as a concert hall and fairground and now in the process of being turned into a permanent exhibition.