One is viewed as among America’s greatest presidents; the other perhaps the worst of all. One is hailed as a savior; the other as a failure. One is given memorials to enshrine his name for all time; the other is pushed into the sea of forgetfulness.

Driven by academia, this is where American history has placed Franklin Delano Roosevelt (in office 1933-1945) and Warren Gamaliel Harding (in office 1921-1923). It is impossible to see FDR absent a “great presidents” ranking; it is likewise impossible to see Harding absent the lowest rungs.

Both men came into office with an economy in tatters and both men instituted ambitious agendas to correct the respective downturns. Yet their policies were the polar opposite of one another and, as a result, had the opposite effect. In short, Harding used laissez faire-style capitalism and the economy boomed; FDR intervened and things went from bad to worse.

Despite these clear facts, in C-SPAN’s latest poll ranking US presidents, FDR finished third in the rankings, while Harding finished 37th. Surveying how both handled the economy, scholars ranked FDR third in that category, while Harding came in at 32. This is a tragedy of history.

America in 1920, the year Harding was elected, fell into a serious economic slide called by some “the forgotten depression“. Coming out of World War I and the upheavals of 1919, the economy struggled to adjust to peacetime realities, falling into a serious slump.

The depression lasted about 18 months, from January 1920 to July 1921. During that time, the conditions for average Americans steadily deteriorated. Industrial production fell by a third, stocks dropped nearly 50 percent, corporate profits were down more than 90 percent. Unemployment rose from 4 percent to 12, putting nearly 5 million Americans out of work. Small businesses were devastated, including a Kansas City haberdashery owned by Edward Jacobson and future president Harry S. Truman.

The nation’s finances were also in shambles. America had spent $50 billion on the Great War, more than half the nation’s GNP (gross national product). The national debt jumped from $1.2 billion in 1916 to $26 billion in 1919, while the Allied Powers owed the US Treasury $10 billion. Annual government spending soared more than twenty-five times, from around $700 million in 1916 to nearly $19 billion in 1919.

Harding campaigned on exactly what he wanted to do for the economy – retrenchment. He would slash taxes, cut government spending, and roll back the progressive tide. He would return the country to fiscal sanity and economic normalcy.

“We need a rigid and yet sane economy, combined with fiscal justice,” he said in his inaugural address, “and it must be attended by individual prudence and thrift, which are so essential to this trying hour and reassuring for our future”.

The business community expressed excitement about the new administration. The Wall Street Journal headlined on Election Day, “Wall Street sees better times after election”. The Los Angeles Times headlined the following day, “Eight years of Democratic incompetency and waste are drawing rapidly to a close”. Others read “Harding’s Advent Means New Prosperity” and “Inauguration ‘Let’s Go!’ Signal to Business”.

The day after Harding’s inauguration, the Times editors predicted “good times ahead”, writing, “The inauguration yesterday of President Harding and the advent of an era of Republicanism after years of business harassment and uncertainty under the Democratic regime were hailed” by the nation’s business leaders. I. H. Rice, the president of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association, told the press, “Good times are now ahead of us. Prosperity is at our door. We are headed toward pre-war conditions … Business men are well pleased with President Harding’s selections for his Cabinet and by the caliber of men he has chosen we know that he means business”.

Under Harding and his successor, Calvin Coolidge, and with the leadership of Andrew Mellon at Treasury, taxes were slashed from more than 70 percent to 25 percent. Government spending was cut in half. Regulations were reduced. The result was an economic boom. Growth averaged 7 percent per year, unemployment fell to less than 2 percent, and revenue to the government increased, generating a budget surplus every year, enough to reduce the national debt by a third. Wages rose for every class of American worker. It was unparalleled prosperity.

Ryan S. Walters, “The Two Presidents Whose Economic Policies Are Most Misunderstood by Historians”, Foundation for Economic Education, 2022-03-05.

February 21, 2026

QotD: Warren G. Harding’s successful depression-breaking policies

October 7, 2025

An unexpected Gen Z “influencer” – Shakespeare

Ted Gioia describes the plight of a young man who had to move home after college and falls into a state of depression thanks to his hopeless situation and his dysfunctional home and social life. His name is Hamlet:

This was long thought to be the only portrait of William Shakespeare that had any claim to have been painted from life, until another possible life portrait, the Cobbe portrait, was revealed in 2009. The portrait is known as the “Chandos portrait” after a previous owner, James Brydges, 1st Duke of Chandos. It was the first portrait to be acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 1856. The artist may be by a painter called John Taylor who was an important member of the Painter-Stainers’ Company.

National Portrait Gallery image via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s almost uncanny how relevant it feels right now.

So if I were directing Hamlet in the current moment, I’d give the title character an iPhone and game console. I’d have the characters onstage share photos on Instagram — and put up a big screen so the audience could see them posted in real time.

Hamlet could add pithy captions to his social media images. What a piece of work is a man! or maybe The lady doth protest too much!

Yes, Hamlet is many things, but one of them is, perhaps, a failed influencer.

Along the way, we may have answered the classic question about this play. For generations, critics have wondered why Hamlet wastes so much time, and can’t be bothered to take action.

Maybe he’s just too busy gaming and scrolling.

Okay, it sounds ridiculous. But is it really? Shakespeare possessed tremendous insight into the human condition — perhaps more than any author in history. So maybe he really did grasp the dominant personality types of our own time.

The Prince of Denmark still walks in our midst. And maybe — just maybe — careful attention to this play might help us, in some small degree, to heal the Hamlets all around us. Their number is legion.

Of course, the larger reality is that Shakespeare has proven himself relevant to every time and place. We can see that easily be examining how other generations viewed this same play.

Hamlet‘s original audience, four hundred years ago, clearly enjoyed the spectacle of violence and adultery. Nine key characters die during the course of the play — most of them murdered. Audiences loved these kinds of dramas back then, and Shakespeare always knew how to please the crowd.

But more sophisticated viewers, circa 1600, would have seen Hamlet as a political commentary — a reflection of all the tensions and rivalries of Elizabethan England. Nobody knew better than Shakespeare that monarchy is a dangerous game, and he always looked for opportunities to refer to current events in roundabout ways.

But two hundred years later, the Romanticists were in ascendancy, and they saw Hamlet as a very different kind of play. They ditched the politics, and embraced the Prince of Denmark for his pathos and personality. They tapped into the intense emotional currents of Shakespeare’s heroes — and the plays seemed perfectly suited for this kind of interpretation.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Hamlet continued to change for each new generation. He always feels timely and relevant.

A hundred years ago, critics began grappling with psychology and the unconscious — and Hamlet was a perfect character for these kinds of interests. In his 1900 book The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud focused on Hamlet as a case study in repression.

And who could disagree?

But fifty years later, Hamlet changed again. It now was the perfect play for those who had survived World War II. Jan Kott insists, in his book Shakespeare, Our Contemporary, that these old plays were more relevant than ever during the Cold War — just as timely as Beckett or Sartre or Brecht or Ionesco.

May 15, 2025

“You can earn a degree in economics without ever encountering the Depression of 1920-1921”

Most modern economists focus on the lessons learned (and not learned) from the Great Depression, but as John Phelan points out, a better learning experience occurred nearly a decade earlier:

In July 1921, the United States emerged from a depression. Though the economic statistics of the time were rudimentary by modern standards, the numbers confirm that it had been bad.

By one estimate, output fell by 8.7 percent in real terms. (For comparison, output fell by 4.3 percent in the Great Recession of 2007-2009). From 1920 to 1921, the Federal Reserve’s index of industrial production fell by 31.6 percent compared to a 16.9 percent fall in 2007-2009. In September 1921, there were between two and six million Americans estimated unemployed: with a nonagricultural labor force of 31.5 million, this latter estimate implies an unemployment rate of 19 percent.

“In this period of 120 years,” wrote one contemporary, “the debacle of 1920-21 was without parallel”.

And then it was over. From 1921 to 1922, industrial production jumped by 25.9 percent and residential construction by 57.9 percent. Manufacturing employment increased by 9.5 percent and real per capita income by 5.9 percent. The 1920s began to roar.

What caused the crash of 1920-1921? Why was it so short? And why was the economic recovery so vigorous?

[…]

Bust to Recovery

As output slumped and unemployment soared, there were those urging action. In December 1920, Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams wrote:

It is poor comfort to the man or woman with a family denied modest comforts or pinched for necessities each week to be told that all will be, or may be, well next year, or the year after. Privations and mortifications of poverty can not be soothed or cured by assurances of brighter and better days some time in the future. Our hope and purpose must be to forestall and prevent suffering and privation for the people of today, the children who are growing up and receiving now their first impression of life and their country.

No such policies were forthcoming.

In October 1919, Woodrow Wilson, then entering the last year of his presidency, was incapacitated by a stroke and his administration ground to a halt: “our Government has gone out of business”, wrote the journalist Ray Stannard Baker.

Wilson’s successor Warren G. Harding, who took office in March 1921, supported Strong’s policies, noting “that the shrinkage which has taken place is somewhat analogous to that which occurs when a balloon is punctured and the air escapes”.

While lower prices meant reduced incomes for some, they meant reduced costs for others. Eventually, producers and consumers started to buy again. By March 1921, lead and pig iron prices bottomed out: cottonseed oil, cattle, sheep, and crude oil followed by midsummer.

The higher interest rates had attracted gold. From January 1920 to July 1921, foreign bullion augmented the American gold stock by some $400 million to $3 billion. By May 1921, 80 percent of the volume of Federal Reserve notes was supported by gold. Interest rates could fall.

In April, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston cut its main discount rate from 7 to 6 percent. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York followed suit next month, cutting from 7 to 6.5 percent. The Roaring Twenties began.

The Lessons

Students of macroeconomics will learn about the Great Depression of the 1930s. They will learn that many of the policies routinely used to fight downturns now — fiscal stimulus and expansive monetary policy — were forged in those years. You can earn a degree in economics without ever encountering the Depression of 1920-1921. Yet, initially, it was as bad as that which began in 1929 but ended more quickly and was followed by a rapid recovery.

Whereas the policymakers of the 1930s — led by the defeated vice-presidential candidate of 1920, Franklin D. Roosevelt — diagnosed the economic problem facing them as unemployment and deflation, those of 1920 diagnosed it as the preceding inflation. Where policymakers of the 1930s used cheap money and government spending to boost demand, those of the 1920s saw this as simply repeating the errors which had created the initial problem. To them, there could be no true cure that didn’t deal with the disease, rather than the symptoms.

It is for history to judge who was correct, but it’s undeniable that the recovery of the Depression of 1920–1921 was immensely stronger and faster than that of the Great Depression. Ironically, this may be the very reason it is often overlooked in history and economic courses.

An additional lesson of eternal relevance can also be drawn: successful solutions will be those which are based on a correct diagnosis of the problem.

May 4, 2025

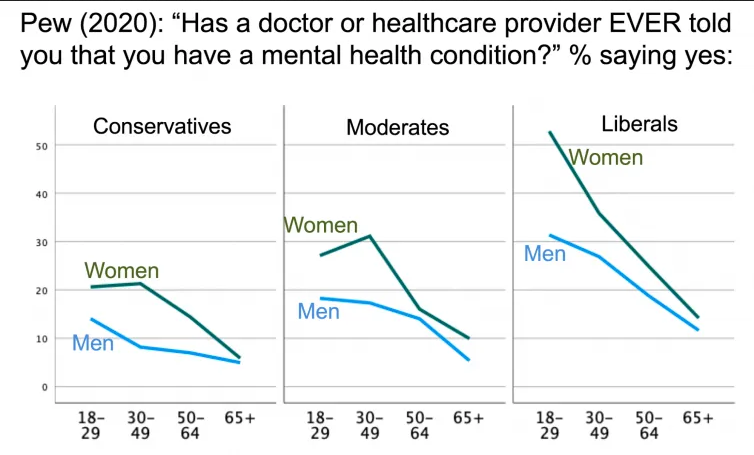

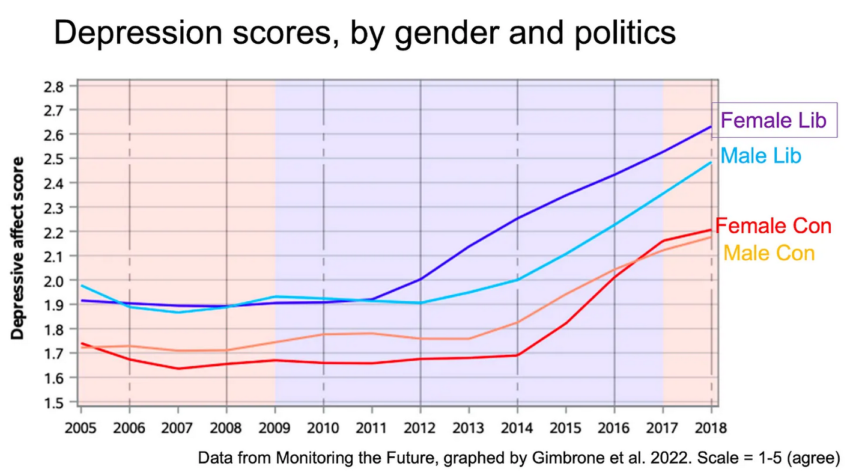

QotD: Women and depression

Why wouldn’t powerlessness cause depression in women too?

Well, in a backwards sort of way it actually does.

The difference is this: women feel powerful when they are loved, and powerless when they are not, because their instinct wiring tells them that safety lies in being able to form social coalitions and attract a strong mate.

Women, in general (there are always outlier exceptions) don’t get major antidepressive help from just going outside and chopping up a cord of firewood, the way men do. Because the woman’s game is to give a man a good reason to chop firewood for her.

It’s when she can’t do *that* that she feels powerless.

ESR, Twitter, 2024-05-06.

March 26, 2025

QotD: Therapy that works for women doesn’t necessarily work for men

The most important thing I’ve learned about human psychology in the last five years: therapy for depression in men is usually mistargeted and ineffective because therapists think men are like women, who become depressed because they don’t feel loved.

This is completely wrong. Men cope with feeling unloved relatively easily. What destroys them is feeling powerless.

So yeah. Swing a sword. Restore a steam engine. Climb a rock. Do something — anything — that asserts your competence and control over your environment.

For men, this is much better therapy than talking about feelings.

ESR, Twitter, 2024-05-06.

August 11, 2023

The Weirdest Boats on the Great Lakes

Railroad Street

Published 5 May 2023Whalebacks were a type of ship indigenous to the Great Lakes during the late 1890s and mid 1900s. They were invented by Captain Alexander McDougall, and revolutionized the way boats on the Great Lakes handled bulk commodities. Unfortunately, their unique design was one of the many factors which led to their discontinuation.

(more…)

March 14, 2023

May 29, 2021

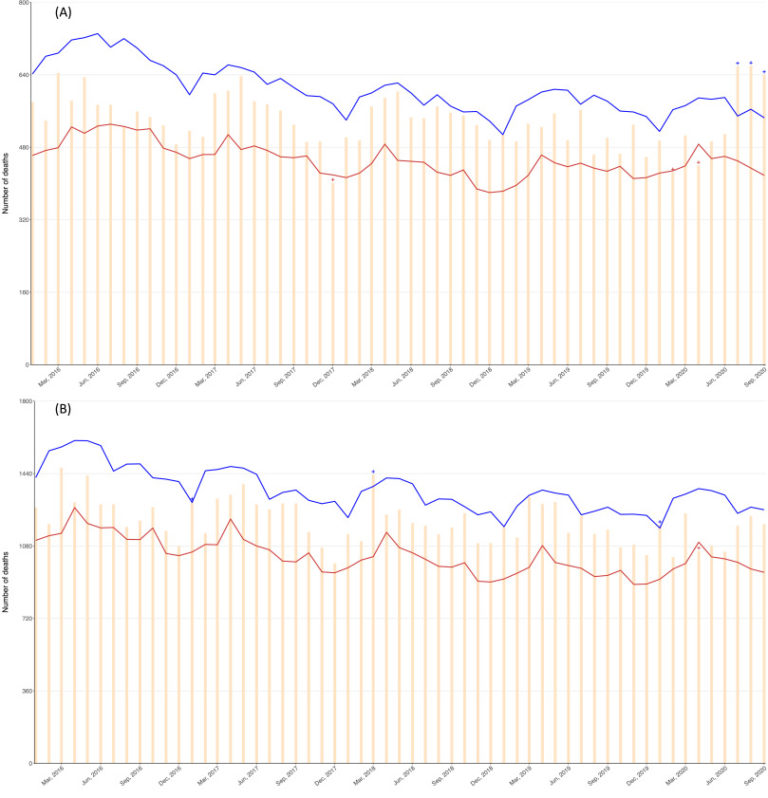

Depression and suicide rates during the Wuhan Coronavirus pandemic

At Works in Progress, Scott Alexander looks at the details of rates of depression (which went up during the pandemic) and suicides (which surprisingly went down):

When COVID started spreading, life got more depressing, people became more depressed, but suicide rates went down. Why?

First, are we sure all of that is true? I won’t waste your time listing the evidence that life got more depressing, but what about the other two?

Ettman et al. conveniently had data from nationally representative surveys about how many Americans were depressed before COVID-19. They found another nationally representative sample and asked them the same questions in late March/early April 2020, when the first wave of US cases and lockdowns was at its peak. They found that 3 times as many people had at least one depression symptom, and 5–10x as many people scored in the range associated with “moderately severe” or “severe” depression.

This is a good study. It’s published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a good journal. It’s been cited 50+ times in 6 months. Really the only thing anyone could have against it is the implausibly large effect it found. But it matches similar studies from Australia, Portugal, and around the world. Let’s say it’s real.

Along with the increased depression came an increase in people who said they were thinking about suicide. According to the US CDC, more than twice as many Americans considered suicide in spring 2020 compared to spring 2018 (10.7% vs. 4.3%).

Yet completed suicide rates stayed flat or declined. It’s hard to tell exactly which, because suicide is rare and noisy, and you need lots of data before anything starts looking statistically significant. But there are studies somewhere between “flat” and “declined” from Norway, England, Germany, Sweden, and New Zealand.

We also have two more complete reports from larger countries that help us see the pattern in more detail. First is Japan. Studies by Tanaka and Nomura broadly agree on a similar pattern — a slight decrease in suicides in the earliest stage of the pandemic (spring 2020) followed by a larger increase during the autumn. Here’s Nomura’s data:

The top graph is women, the bottom is men. The blue and red lines represent the 95% confidence range for an “average” year. Months that differ significantly from the average have little dots on top of their bars. You can see that April 2020 had significantly less suicide than average, among both genders, and July/August/September have more than average for women (and trend on the high side for men too).

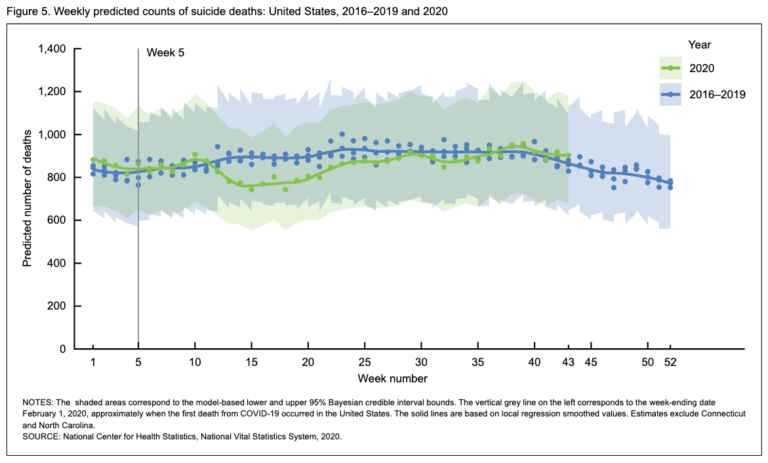

Second is the US. The US Centers for Disease Control recently released their “nowcast” of 2020 deaths. These use the limited amount of data they have now to predict what the trends will look like once all the data comes in; their prediction process seems reasonable and we can probably treat the figures as canonical. Here’s their main result:

Suicide rates were pretty normal until March, when they dropped off pretty quickly and stayed low until midsummer. They’ve since hovered around normal again. Overall, suicides declined by 5.6%.

All these countries combine to form a picture of suicide rates dipping very slightly during the first and most frantic period of the pandemic — March to May — and then going back to normal (except in Japan, where things have since gotten worse). Thus the paradox: increasing depression combined with decreasing suicides. What’s going on?

May 23, 2021

QotD: The psychological impact of extended lockdowns

Claudio Grass (CG): A lot has been said and written about the economic and financial impact of the covid crisis and all the lockdowns and restrictions that came with it. However, the mental health implications haven’t really received the attention they arguably merit, at least not by mainstream media or government officials. Over the last year, we saw self-reported depression rates creep up in many Western nations, while excessive alcohol consumption and the abuse of prescription drugs also jumped. Do such trends raise concerns over longer-term problems or will we all simply snap back to normal once the crisis is over?

Theodore Dalrymple (TD): The first thing to say is that I do not like the term “mental health.” Was Isaac Newton mentally healthy, or Michelangelo? I think part of the problem is very concept of mental health. It implies that there is some state or condition of mind deviation from which is analogous to illness. Once this idea takes hold, it is clearly up to an expert to cure the person, or better still prevent him from getting ill in the first place. This expectation cannot be met, but the idea that it can be makes people more fragile.

Second, people clearly vary much in their response to confinements, lockdowns, closures of resorts of entertainment, etc. For myself, I have reached the age of misanthropy or self-sufficiency when these things make comparatively little difference to my life. I have plenty of space and plenty of things to do, in essence reading and writing. But that does not make me mentally healthier than a young man who is frustrated because he cannot play football with his friends and becomes ratty – moreover living in a very confined space.

Depression is so loosely defined a term that it has become almost valueless as a diagnosis. How often have you heard someone say “I’m unhappy” rather than “I’m depressed?” The semantic shift is very important. The proper response to someone who says that he is depressed is to give him antidepressants, even though these don’t work in the majority of cases, except as a placebo, and have potential side-effects. It is always tempting for people who are unhappy to drink alcohol – to drown their sorrows, as we say. Of course, if you drink too much, you might become really and truly depressed. A person who did not respond to the current situation with a little gloom would be odd.

Claudio Grass, “Theodore Dalrymple: Self-Control And Self-Respect Have Become Undervalued”, The Iconoclast, 2021-02-17.

March 3, 2021

Gen Z is suffering … but not enough?

In Quillette, Freya India considers the plight many of her cohort find themselves in during the ongoing efforts to combat the spread of the Wuhan Coronavirus (aka Covid-19):

“Gen Z” by EpicTop10.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

My generation is miserable. Gen Z, those of us born after 1997, are the saddest, loneliest, and most mentally fragile age group to date, cursed with rising rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide. How can that be? How can a generation with everything feel so desperately unhappy? By almost every metric, human life is dramatically better today than it ever has been. The number of people living in extreme poverty has fallen from around 90 percent in 1820 to just 10 percent in 2015, while rates of illiteracy, mortality, and battle deaths are also in rapid decline. For the most part, Gen Z are heirs to an immense fortune: a utopian world of instant gratification and technological dynamism. In theory, this should be the age of happiness.

And yet, misery abounds. In the United States, 54 percent of Gen Z report anxiety and nervousness, according to researchers at the American Psychological Association. This is compared with only 40 percent of millennials and a national average of 34 percent. It isn’t just a case of self-report bias either, since the suicide rate for Americans aged between 15 and 24 has risen by over 51 percent in the last decade. For Gen Z women in particular, suicide rates have risen a staggering 87 percent since 2007. In my home country of the UK, one in four girls is clinically depressed by the time they are 14.

There’s no shortage of articles trying to make sense of the mental health epidemic at a time of such global prosperity. Teens and pre-teens today, we’re told, are simply interred beneath the weight of political issues like climate change, immigration, and sexual assault, as well as fatigued by job stress, exam burnout, and the attainment of unrealistic social media standards. The antidote, many suggest, lies in practicing better “self-care,” from daily gratitude journaling to adopting a 38-step skincare routine. And it’s a popular remedy. Since the pandemic began, online searches for “self-care” have risen 250 percent, with schools, universities, and employers turning to compulsory wellness programmes like mindfulness training and meditation sessions to improve mental health.

But, I suspect the problem is more nuanced than this. I don’t doubt that Gen Z is under a lot of strain, but I also think our plight is unique. For the first time in history, much of our misery stems not from too much suffering, but from not suffering enough. Gen Z does face real problems. I have certainly felt beleaguered by the pressures of social media, an oversaturated job market and the impact of coronavirus restrictions on my education. On top of that, there’s the difficulty of simply trying to exist as a fallible human in a political climate which demands infallibility, where nothing feels light-hearted anymore, and everything we say or do in our youth is stained onto the Internet for all time.

So, pressure is no doubt part of it. But previous generations faced egregiously difficult times: world wars, pandemics, economic crises, political rebellions, totalitarian regimes, and conditions of extreme poverty. Not only that, but today there are a wider range of mental health services available than ever before, and Gen Z are more likely than any other generation to seek treatment. So, for our rates of mental illness and suicide to be so high in a time of relative peace, there must exist a more convincing explanation than simply the asperities of life.

What lurks over my generation is not just a sense of misery, but meaninglessness. We exist in a state of lethargy and unfulfillment, tormented not by the tragedy of it all, but the futility. This is a point most articles and public figures today are less willing to discuss. But, to examine this possibility isn’t to say that Gen Z never struggle — but to suggest that at least some of us are caught in a rut of boredom, not burnout.

October 22, 2018

Looting – Pilates – Suicides Among Soldiers I OUT OF THE TRENCHES

The Great War

Published on 20 Oct 2018Crisis Call Center (US): http://crisiscallcenter.org/crisisser…

Crisis Service Canada: http://www.crisisservicescanada.ca/

Mind (UK): https://www.mind.org.uk/

Deutsche Depressionshilfe: https://www.deutsche-depressionshilfe…

May 3, 2018

QotD: Resisting the black dog

Last week I was having a bad day — nothing tragic, just adult life’s vicissitudes — when I got an email from a complete stranger that knocked me on my ass.

I’ll call this guy John. John recently survived a brush with suicidal depression and anxiety. John’s story is both terrifying and inspiring because he faced that depression without a job, without medical insurance, and (until he reached out for help) without a support network, and came out on the other end. John took a leap of hope, sought help from a loved one, got treatment, and got through the crisis. Is he happy all the time? I doubt it. Who is? But he’s managing the illness successfully and living his life.

John thanked me for writing openly about my experiences with severe depression and anxiety and how they have changed my life. He expressed a sentiment that I also experienced as a powerful deterrent to getting help: the fear that medication, or hospitalization, and therapy somehow mark you as other and lead to the end of your plans and ambitions forever. It’s not true. It helps, John said, to see other people who have fought mental illness, taken the plunge into serious treatment, and come out the other side continuing to pursue their careers and families and lives. John thanked me for writing, and said I made a difference for him and helped him imagine recovery as a possibility. I’m going to remember that on my worst days, when I’m down on myself.

People who have fought mental illness — people who are still struggling with it, every day — can change people’s lives by offering hope.

Depression and anxiety are doubly pernicious. They don’t just rob you of your ability to process life’s challenges. They rob you of the ability to imagine things getting better — they rob you of hope. When well-meaning people try to help, they often address the wrong problem. “Your relationship will work out if you just talk,” or “I’m sure your boss doesn’t actually hate you,” or “things will look up and you’ll find another job” may all be true, and may all be good advice. But they don’t address the heart of mental illness. A depressed or anxious person isn’t just burdened with life’s routine problems. They’re burdened with being unable to think about them without sheer misery, and being unable to conceive of an end to that misery continuing, endlessly, in response to one problem after another. Solving the problems, one by one, doesn’t solve the misery.

The hope you can offer to someone who is depressed or anxious isn’t your problems will all go away. They won’t. That’s ridiculous (though certainly it’s much easier to solve or avoid problems when you’re not debilitated). The hope you can offer is this: you will be able to face life’s challenges without fear and misery. The hope isn’t that your life will be perfect. The hope is that after a day facing problems you’ll still be able to experience happiness and contentment. The hope is that you’ll feel “normal” again.

Ken White, “Why Openness About Mental Illness is Worth The Effort And Discomfort”, Popehat, 2016-08-09.

November 14, 2017

QotD: Depressive writing leads to depressed readers

Agatha Christie gave her characters foibles, sure, and often there was a tight intrigue and not just the murderer but two or three other people would be no good. BUT the propensity of the characters gave you the impression of being good sort of people. Perhaps muddled, confused, or driven by circumstances to the less than honorable, but in general driven by principles of honor or love (even sometimes the murderer) and wanting to do the right thing for those they cared about.

You emerge from a Christie memory with the idea, sure, that of course there was unpleasantness, but most of the people are not horrors.

How did we get from there to now, where the characters aren’t even evil? They’re just dingy and grey and tainted, all of them equally. The victim, the detectives, the witnesses, will be vile and contorted, grotesque shapes walking in the world of men.

If this is a reflection of the psyches of most authors, I suddenly understand a lot about the self-hatred of western intellectuals.

But I wonder if it’s a fashion absorbed and perpetuated, communicated like the flu, a low grade dingy patina of … not even evil, just discontent and depression and a feeling that everyone in the world is similarly tainted.

I realized that was part of what was depressing me, partly because I’m a depressive, so I monitor my mood fairly regularly. BUT what about normal people? What if they just absorb this world view — and the idea that it’s smart and sophisticated, too — through popular entertainment, through movies and books and shows and then spew it out into the world, because it stands like a veil between them and reality, changing the way they perceive everything.

[…] such despairing stuff, such low grade despair and unpleasantness change us, particularly when they’re unremitting. You internalize these thoughts, they become part of you. If humanity is a plague, who will have children? If humanity is a plague, why not encourage the criminals and terrorists? If humanity is a plague who is clean?

You. Me. Most human beings. Oh, sure, we’re not perfect — I often think people who write this lack the ability to distinguish between not being perfect and being corrupt and evil — and we often have unlovely characteristics. But, with very few exceptions, most people I know TRY to be decent by their lights, try to raise their kids, help their friends and generally leave the world a little better.

Now, are we representative of everyone? Of course not. A lot of people are raised in cultures (here and abroad) that simply don’t give their best selves a chance. But why enshrine those people and not the vast majority who are decent and well… human?

Even in a mystery there should be innocent and well-intentioned people. It gives contrast to the darker and more evil people and events.

Painting only in dark tints is no more accurate than painting only in pale tints. It doesn’t denote greater artistry. It just hangs a grey, blotched veil between your reader and reality, a veil that hides what is worthwhile in humans and events.

Make yourself aware of the veil and remove it. It’s time the low-grade depression of western civilization were defeated. No, it’s not perfect, but with all its failings it has secured the most benefits to the greatest number of people in the long and convoluted history of mankind. Self-criticism might be appropriate, but not to the exclusion of everything else.

Say no to the dingy-grey-patina. Wash your eyes and look at the world anew. And then paint in all the tints not just grey or black.

Sarah Hoyt, “A Dingy Patina”, According To Hoyt, 2015-10-22.

April 26, 2017

The End of Play: Why Kids Need Unstructured Time

Published on 25 Apr 2017

“School has become an abnormal setting for children,” says Peter Gray, a professor of psychology at Boston College. “Instead of admitting that, we say the children are abnormal.”

Boston College Psychology Professor Peter Gray says that a cultural shift towards a more interventionist approach to child rearing is having dire consequences for the well-being of kids. “Over the same period of time that there has been a gradual decline in play,” he told Reason‘s Nick Gillespie, “there are well documented, gradual, but ultimately huge increases in a variety of mental disorders in childhood — especially depression and anxiety.”

Gray believes that social media is one saving grace. “[Kids] can’t get together in the real world…[without] adult supervisors,” he says, “but they can online.”

For more on Gray’s work, follow his blog at Psychology Today.

Edited by Mark McDaniel. Cameras by Todd Krainin and Jim Epstein. Music by Broke for Free.

October 8, 2016

QotD: Depression

The book [In the Jaws of the Black Dogs, (1999)] is a compelling, unpleasant read, valuable because it tells us three things. First, that such depressions do not yield to shrink fixes, and will not otherwise “go away.” Second, that there is no “template,” for each sufferer is his own constellation of symptoms which no outsider is privileged to explore. And thus, third, the depression can be controlled and mastered, only if one grasps these things. One must, as it were, leash one’s own black dogs, and it will be neither easy nor painless. While perhaps overwritten, the book is admirable for containing no victim’s plaint, no false appeal for applause, and absolutely no pop psychology.

David Warren, “Unfinished conversations”, Essays in Idleness, 2016-09-19.