Uri Tuchman

Published 12 Jul 2019Preserved lemon recipe:

For the lemons:

– 6 lemons

– 300 gram salt

Cutting board:

– 40x25x1.5 cm cherry wood

Knife:

– 20x5x0.2 cm O1 steel

– 10x3x2 cm Maple wood

– 4x3x2 cm walnut wood

Airtight container:

– 14x14x1.5 cm cherry wood x2

– 10x14x1.5 cm cherry wood x4

– brass screw rod x8

– brass thumb nut x8

Serving board

– 20x6x1.5 cm beech wood

– 6x1x0.5 cm walnut

Fork:

– 6x1x0.2 cm brass plate

– 1cm brass tube

– 10 wooden handle from some nice burlMix everything in a bowl and you’re golden!

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/urituchman

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/urituchman/Music:

Acid Trumpet

Kevin MacLeod

incompetech.com)

Licensed under Creative Commons: By Attribution 3.0 License

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/b…

April 1, 2021

How to Make Preserved Lemons in the Workshop

March 21, 2021

The two Britains, gastronomically speaking

Theodore Dalrymple on the British diet (at least before the neverending lockdowns):

“The Joy of Cookbooks” by shoutabyss is licensed under CC BY 2.0

As in many other things, the population has divided into two: those with increasingly refined tastes in gastronomy, and those who eat mainly junk and takeaway food for the quickest but also crudest possible gratification.

Gastronomy often seems the only aesthetic sphere in which the modern British display any real interest. Their dress, their music, their art (or at least such as gains any publicity), their literature, and of course their architecture, are hideously ugly, even militantly so, but a Michelin-starred restaurant receives their adulation — or did in the now-distant days when restaurants were open.

But the modern interest in food is not the same as a mass market for fish, which has, alas, mainly to be cooked, and the fact is that the British are, grosso modo, too lazy and ignorant to cook properly. Many millions of them would be horrified by the sight of a whole fish, or even any part of a raw fish: they don’t want to eat anything that hasn’t been through a complex industrial process, had chemicals and preservatives added to it, and cannot be just stuck in a microwave for a few minutes before consumption in front of the television. Besides, they wouldn’t know what to do with a fish, let alone a crustacean.

It is said that about a fifth of British children do not eat a meal with another member of their household (family would, perhaps, be a misleading term) more than once a fortnight, turning meals into asocial and even furtive occasions. Many households do not have a dining table, and in my visiting days as a doctor I discovered that the microwave is often a household’s entire batterie de cuisine.

This slovenly and asocial approach to eating — evident in the detritus left behind in British streets as people eat wherever they happen to be, in their cars, walking along, in trains and buses, in fact anywhere but a dining room and with others — is not the consequence of poverty, but of a degraded style of life.

Many years ago I noticed that shops in poor areas where there were many immigrants of Indian origin had enormous piles of a vast array of vegetables so cheap that the problem was carrying them home rather than their cost. I would see Indian housewives selecting their purchases with care and attention: the quality and not just the price mattered to them. Uncompelled by economic necessity to shop there, I would nevertheless do so; but I never saw poor whites doing so. The problem with all those vegetables was that they required cooking, preferably with skill, which very few poor whites, as against poor Indians, had. And this is a cultural problem, if the taste for and consumption of a diet of junk food (what the French more vividly call malbouffe) is a problem.

The Indians are fat, with bad health consequences, from eating too much good food; the native British, with bad health consequences, from eating too much bad food. The prevalence of obesity in Britain, greater than in most other European countries, is possibly one of the reasons that its death rate from COVID-19 is so high, among the highest if not actually the highest. And this obesity is immediately obvious on arrival in Britain from any European country.

March 19, 2021

QotD: English food

For someone who remembers the old days, the food is the most startling thing about modern England. English food used to be deservedly famous for its awfulness — greasy fish and chips, gelatinous pork pies, and dishwater coffee. Now it is not only easy to do much better, but traditionally terrible English meals have even become hard to find. What happened?

Maybe the first question is how English cooking got to be so bad in the first place. A good guess is that the country’s early industrialization and urbanization was the culprit. Millions of people moved rapidly off the land and away from access to traditional ingredients. Worse, they did so at a time when the technology of urban food supply was still primitive: Victorian London already had well over a million people, but most of its food came in by horse-drawn barge. And so ordinary people, and even the middle classes, were forced into a cuisine based on canned goods (mushy peas!), preserved meats (hence those pies), and root vegetables that didn’t need refrigeration (e.g. potatoes, which explain the chips).

But why did the food stay so bad after refrigerated railroad cars and ships, frozen foods (better than canned, anyway), and eventually air-freight deliveries of fresh fish and vegetables had become available? Now we’re talking about economics — and about the limits of conventional economic theory. For the answer is surely that by the time it became possible for urban Britons to eat decently, they no longer knew the difference. The appreciation of good food is, quite literally, an acquired taste — but because your typical Englishman, circa, say, 1975, had never had a really good meal, he didn’t demand one. And because consumers didn’t demand good food, they didn’t get it. Even then there were surely some people who would have liked better, just not enough to provide a critical mass.

And then things changed. Partly this may have been the result of immigration. (Although earlier waves of immigrants simply adapted to English standards — I remember visiting one fairly expensive London Italian restaurant in 1983 that advised diners to call in advance if they wanted their pasta freshly cooked.) Growing affluence and the overseas vacations it made possible may have been more important — how can you keep them eating bangers once they’ve had foie gras? But at a certain point the process became self-reinforcing: Enough people knew what good food tasted like that stores and restaurants began providing it — and that allowed even more people to acquire civilized taste buds.

Paul Krugman, “Supply, Demand, and English Food”, https://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/mushy.html.

February 13, 2021

MORE cultural appropriation foods!

J.J. McCullough

Published 14 Nov 2020How much famous food is just copied from some other country? Thanks to Jack Rackham for the shogun animation!

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCaQz…FOLLOW ME:

🇨🇦Support me on Patreon! https://www.patreon.com/jjmccullough

🤖Join my Discord! https://discord.gg/3X64ww7

🇺🇸Follow me on Instagram! https://www.instagram.com/jjmccullough/

🇨🇦Read my latest Washington Post columns: https://www.washingtonpost.com/people…

🇨🇦Visit my Canada Website http://thecanadaguide.comHASHTAGS: #food #cooking #history

January 19, 2021

QotD: British foods

… it is worth listing the foodstuffs, natural or prepared, which are especially good in Britain and which any foreign visitor should make sure of sampling.

First of all, British apples, one or other variety of which is obtainable for about seven months of the year. Nearly all British fruits and vegetables have a good natural flavour, but the apples are outstanding. The best are those that ripen late, from September onwards, and one should not be put off by the feat that most British varieties are dull in colour and irregular in size. The best are the Cox’s Orange pippin, the Blenheim Orange, the Charles Hoss, the James Grieve and the Russet. These are all eaten raw. The Bramley Seedling is a superlative cooking apple.

Secondly, salt fish, especially kippers and Scottish haddocks. Thirdly, oysters – very large and good, though artificially expensive. Fourthly, biscuits, both sweetened and unsweetened, especially those that come from the four or five great firms whose names are a trademark. Fifthly, jams and jellies of all kinds. These are usually best when home-made, with the exception of strawberry jam, which is nearly always better as a manufactured product. Some varieties not often seen outside Britain are blackcurrant jelly, bramble jelly (made of blackberries) marrow jam with ginger, and damson cheese, an especially stiff kind of jelly which can be cut in slabs. In addition, no one who has not sampled Devonshire cream, Stilton cheese, crumpets, potato cakes, saffron buns, Dublin prawns, apple dumplings, pickled walnuts, steak-and-kidney pudding and, of course, roast sirloin of beef with Yorkshire pudding, roast potatoes and horseradish sauce, can be said to have given British cookery a fair trial.

The only alcoholic drinks which are native to Britain, and are all widely drunk, are beer, cider and whiskey. The cider is fairly good (that brewed in Herefordshire is the best), the beer very good. It is somewhat more alcoholic and very much bitterer then the beers of most other countries, all save the mildest and cheapest kinds being strongly flavoured with hop. Its flavour varies greatly from one part of the country to another. The whiskey exported from Britain is mostly Scottish, but the Irish kind, which is sweeter in taste and contains more rye, is also popular in Britain itself. One excellent liquor, sloe gin, is widely made in Britain, though not often exported. It is always better when home-made. It is of a beautiful purplish-red colour, and rather resembles cherry brandy, but is of a more delicate flavour.

Finally, a word in praise of British bread. In general it is close-grained, rather sweet-flavoured bread, which remains good for three or four days after being baked. It is seen at its best in the kind of double loaf. Rye bread and barley bread are hardly eaten in Britain, but the wholemeal wheat bread is extremely good. The great virtue of British bread is that it is baked in small batches, in a rather primitive way, and therefore is not at all standardised. The bread from one baker may be quite different from another down the street, and one can range about from shop to shop until one is suited. It is a good general rule that small, old-fashioned shops make the best-flavoured bread. Throughout a great deal of the North of England the women prefer to bake their bread for themselves.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

December 26, 2020

QotD: British meals – fish, fowl, and vegetables

There are not many methods of cooking birds which are peculiar to Britain. The British regard as inedible many birds – for instance, thrushes, larks, sparrows, curlews, green plovers and various kinds of duck – which are valued in other countries. They are also inclined to despise rabbits, and rabbit-rearing for the table has never been extensively practiced in Britain. On the other hand they will eat young rooks, which are shot in May and baked in pies. They are especially attached to geese and turkeys, which (at normal times) are eaten in immense quantities at Christmas, always roasted whole, with chestnut stuffing in the case of turkeys, and sage and onion stuffing and apple sauce in the case of geese.

Fish in Britain is seldom well cooked. The sea all round Britain yields a variety of excellent fishes, but as a rule they are unimaginatively boiled or fried, and the art of seasoning them in the cooking is not understood. The fish fried in oil to which the British working classes are especially addicted is definitely nasty, and has been an enemy of home cookery, since it can be bought everywhere in the big towns, ready cooked and at low prices. Except for trout, salmon and eels, British people will not eat fresh-water fish. As for vegetables, it must be admitted that, potatoes apart, they seldom get the treatment they deserve. Thanks to the rain-soaked soil, British vegetables are nearly all of excellent flavour, but they are commonly spoiled in the cooking. Cabbage is simply boiled – a method which renders it almost uneatable – while cauliflowers, leeks and marrows are usually smothered in a tasteless white sauce which is probably the “one sauce” scornfully referred to by Voltaire. The British are not great eaters of salads, though they have grown somewhat fonder of raw vegetables during the war years, thanks to the educational campaigns of the Ministry of Food. Except for salads, vegetables are always eaten with the meat, not separately.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

November 15, 2020

Michael Symon’s Essential Knives You Need to Own | Food Network

Food Network

Published 13 Aug 2020Take it from the pro Michael Symon: These are *THE* essential knives you need to make your meal prep quick and efficient! 🔪🔪

Have you downloaded the new Food Network Kitchen app yet? With up to 25 interactive LIVE classes every week and over 80,000 recipes from your favorite chefs, it’s a kitchen game-changer. Download it today: http://food-network.app.link/download!

#SymonDinners, Sundays at 12:30|11:30c.

Follow Food Network on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/foodnetwork/

Follow Food Network on Twitter: https://twitter.com/FoodNetwork

Visit Food Network online: http://www.foodnetwork.com

October 13, 2020

A Single Spice Blend For Your Entire Kitchen – Kitchen Pepper From 1777

Townsends

Published 8 Jul 2020Visit Our Website! ➧ http://www.townsends.us/ ➧➧

Help support the channel with Patreon ➧ https://www.patreon.com/townsend ➧➧

Instagram ➧ townsends_official

October 11, 2020

“Doctrinaire cuisine is dangerous”

Felipe Fernández-Armesto is not a fan of printed recipes, for they quash the creative, adventurous spirit he feels is required for proper cooking:

“The Joy of Cookbooks” by shoutabyss is licensed under CC BY 2.0

I believe in freedom and one of the reasons for my hatred of recipes is their peremptory, commanding tone, as if the writer knew the only way to fashion the dish. Variants from the inflexibly regimented columns of most cookbooks are made to seem like heresies.

Recipes are typically officious and pettifogging, treating readers as idiots, who don’t know how to suit their own taste or adjust traditions.

Many read like nursery-school arithmetic: add x amount of flour and y of milk to z of butter to produce a predictable outcome. Creativity and adventure get no badge. By specifying quantities, the teacher robs cooking of its status as art and turns it into drearily certified schoolkid-science.

Doctrinaire cuisine is dangerous. Friendships founder and marriages crash over differences about whether — for instance — to put onions in Spanish omelette or chillies in curry, or disputes over whether eggs are better scrambled in a deep or shallow dish. I’m happy to leave chacun à son goût in almost everything.

If you want to marmalade your kippers or make mayonnaise with sunflower oil, I’ll despise your mind and denounce your taste, but I’ll defend your right, as thoroughly as if you wanted to vote Republican or learn line-dancing. I’ll tolerate tinned tomatoes in ratatouille, as long as I don’t have to eat it, or rose veal in Wiener schnitzel, or even honey instead of molasses in baked beans.

But there are some abominations that are destructive of happiness, because they deprive eaters of opportunities of enjoyment, or turn wonderful ingredients to waste. Most of them occur in recipes exposed to the internet, where nannies write for nincompoops.

August 25, 2020

How we used to “dine out” (and someday might be able to again)

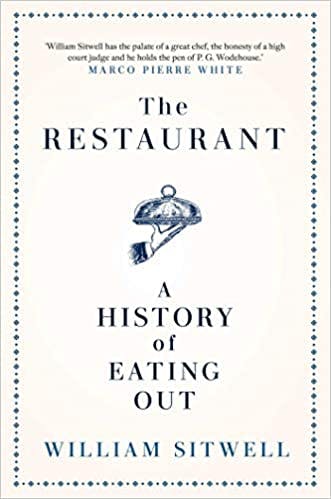

In The Critic, Alexander Larman reviews The Restaurant: A history of eating out by William Sitwell:

The recent enforced lockdown closure was a potential death blow to the entire [restaurant] industry. Which makes William Sitwell’s luxurious book both a celebration and an unintentional requiem for what may be a bygone time.

His central thesis is clear: the history of dining out is also a social history of evolving cultures and tastes. This means that the subjects he writes about range from ancient Pompeii to the growth of the sushi conveyor belt restaurant, encompassing everything from medieval taverns and the French Revolution to the rise of Anglo-Indian cuisine.

It is a broad and impressive spectrum, but perhaps Sitwell has, like some of the less fortunate people he describes, bitten off more than he can chew. His opening chapter about Pompeii is rich in surprising detail (graffiti uncovered outside one tavern when it was excavated ranged from the poetic — “Lovers are like bees in that they lead a honeyed life” — to the crude — “I screwed the barmaid”) and an insightful evocation of the dining culture in Ancient Rome.

He is then, unfortunately, faced with the insurmountable difficulty that the restaurant, as we know it today, did not exist until the late eighteenth century, meaning that his definition of “eating out” has to do some extremely heavy lifting.

There is as much padding in the early chapters as there is around some of his subjects’ waistlines. Much of what he writes is very interesting and often amusing, such as the way in which coffee, first drunk in London around the time of the Restoration, became associated both with health-giving properties and reportedly making men impotent, withered “cock-sparrows”. Yet there are also lengthy sections that have little or nothing to do with restaurants, such as a potted history of the Industrial Revolution.

Nevertheless, when Sitwell finally gets into his stride and begins to write about eateries proper, his authority and enthusiasm are palpable. He describes the dawn of fine dining in Paris in the nineteenth century evocatively. London lagged behind, although gentlemen’s clubs such as the Athenaeum and Reform offered some delights for the wealthy thanks to chefs (French, naturally) such as Alexis Soyer who implemented what one biographer called “the most famous and influential working kitchen in Europe” in 1841, complete with gas-fired stoves, butcher’s rooms and a fireplace devoted to the roasting of game and poultry.

July 27, 2020

Food in Ancient Rome – Garum, Puls, Bread, and Moretum

SandRhoman History

Published 7 Jul 2019Food in ancient Rome – the cuisine of ancient Rome is probably not everybody’s cup of tea. Food in ancient Rome was consumed at the mensa, the dining table of the ancient Romans. A usual ancient Roman meal for the upper classes could look like this: puls, one of the main ancient Roman meals. This was essentially a form of porridge, along with that they might have eaten bread, refined with olives and figs. Bread was often eaten with moretum, a spread, made of sheep cheese, a lot of garlic and herbs. Most Roman meals would have been spiced with garum, a fermented fish sauce, to go along with such a meal, the Romans drank water or wine. Beer, called cervisia, in contrast would have been considered barbaric. The wine was usually diluted with water and sometimes spiced with herbs and vinegar. Water with vinegar was called posca, another variant was mulsum, wine spiced with honey.

Ancient Roman food had even more variety, but for now we just made the recipes below. We might make some more ancient Roman food in the future though.

Ancient Roman recipes:

First off: Put garum into everything. That’s actually what the Romans used, usually instead of salt and/or other condiments. [Consider it the ketchup of the ancient world.]

Garum recipe

– 1000 g small fish (sardines, anchovies or similar, fresh or frozen but uncooked)

– 500 g sea salt

– 2 1∕2 tbsp. dried oregano

– 1 tbsp. dried mint

– 1,5 litres water

– 5 tbsp. honey

Put everything in a pot and cook it until the fish falls apart (ca. 15 minutes). Pestle it with a spoon or similar and reduce this broth for at least 20 minutes. Then strain it, let it cool and strain it again. Additionally, you can pour it through a filter cone to refine the garum even further. Keep the garum in the fridge and throw it away if it gets dreggy.Moretum recipe

– 300 g of ricotta

– 100 g pecorino (or similar hard sheep cheese)

– 3 tbsp. white wine vinegar

– 3 tbsp. sea salt

– 3 cloves of garlic

– a bunch of thyme

– a bunch of rosemary

– a bunch of estragon [tarragon]

– a bunch of coriander

– garum

Press the garlic, grind the pecorino and stir all the ingredients until you get a consistent mass. Done!

Pro tip: You might want to be careful with the amount of salt and especially garlic you add. Three cloves make it very intense.Puls recipe

– 500 g rolled oats

– 1.5 litres of water

– 1 tbsp. olive oil

– 100 g pecorino (or similar hard sheep cheese)

– 1 onion

– 2 carrots

– 150 g mushrooms

– 100 g streaked pork

– garum

Chop all the vegetables and cut the pork into strips. Then roast it gently in a bit of olive oil and put it aside. Cook the rolled oats with some water and add continuously as it disperses until you get a porridge-like consistency. Then add the prepared vegetables and meat and fold in the ground pecorino.

If you want to stay somewhat authentic to the Roman recipe use white, violet or yellow carrots: orange ones weren’t known in the occident until the Middle Ages.Panis militaris castrensis (Roman bread) recipe

Ingredients for one loaf (4 – 6P):

– 500 g spelt flour (whole grain)

– ½ tsp. of salt

– olives

– figs

– 3 tbsp. olive oil

– 1 tsp. honey

– 3 dl water (hand-hot)

– 15 g yeast (or one package of dry yeast)Mix everything up and knead it for at least 15 minutes. Then let it rise for an hour in a bowl covered with a towel (preferably in a warm spot). Form a loaf, cut six pieces (halfway through) and bake it for 35 minutes at 180°C.

Pro tip: take big olives and lots of them because the whole grain flour will be so dense that they kind of disappear.

Those recipes are taken from a cookbook which has been written about 2,000 years ago. Taking this into account you should be rather careful applying these cooking techniques. We are not to be held responsible for any damage resulting, neither for smelly apartments, nor for health issues.

#food #ancientrome #history #ancienthistory #rome

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Sandrhoman

July 7, 2020

Homemade Flatbread in Minutes – How to Make the World’s Oldest Bread

Food Wishes

Published 17 Nov 2014Learn how to make Homemade Flatbread in minutes! Visit http://foodwishes.blogspot.com/2014/1… for the ingredients, more information, and many, many more video recipes. I hope you enjoy this easy, homemade flatbread technique!

June 1, 2020

Buffalo Cauliflower Wings with Blue Cheese Dip – You Suck at Cooking

You Suck At Cooking

Published 5 Feb 2020Buffalo Cauliflower, also known as Buffalo Cauliflower Wings, is based on Buffalo Wings, which are Chicken Wings in Hot Sauce. Who knew that combining food with hot sauce would taste good? Nobody did.

YSAC Book and merch: http://yousuckatcooking.com

http://instagram.com/yousuckatcooking

https://twitter.com/yousuckatcookinRECIPE

• To make this Buffalo Cauliflower, you can start with a small or medium sized cauliflower.

Rip it apart while making loud grunting sounds.

• Combine two tablespoons of olive oil, 1 tablespoon of water, 2 teaspoons of garlic powder, and some salt in a bowl and wangjangle it until there’s no need for further wangjangling because you did a good job.

• Combine the pre-buffalish elixir to the cauliflower in a bigger bowl and gallop around the house. Alternatively, you could have made the elixir in that big bowl to begin with. Now you’re thinking

Throw that cauliflower onto a parchment papered pan and bake it at 450 for 15 minutes.

• Meanwhile, make the Buffalo sauce: two tablespoons of melted butter and ½ cup of pepper sauce.

• Take that cauliflower out of the oven (unless you have an Automated Oven Sauce Dispenser), and put that sauce on the cauliflower in one way or another. You can brush it, spoon it, slather it, or whatever you want.

• Bake it for another 8 minutes or until it’s the texture you like. A bit less for more of the natural cauliflower crunch, a bit more to make it soggier. The choice is yours, even if you make a bad one.

December 23, 2019

QotD: British meals – puddings

Suet crust, which appears in innumerable combinations, and enters into savoury dishes as well as sweet ones, is simply ordinary pastry crust chopped beef suet substituted for the butter or lard. It can be baked, but more often is boiled in a cloth or steamed in a basin covered with a cloth. Far and away the best of all suet puddings is plum pudding, which is an extremely rich, elaborate and expensive dish, and is eaten by everyone in Britain at Christmas time, though not often at other times of the year. In simpler kinds of pudding the suet crust is sweetened with sugar and stuck full of figs, dates, currents or raisins, or it is flavoured with ginger or orange marmalade, or it is used as a casing for stewed apples or gooseberries, or it is rolled round successive layers of jam into a cylindrical shape which is called roly-poly pudding, or it is eaten in plain slices with treacle poured over it. One of the best forms of suet pudding is the boiled apple dumpling. The core is removed from a large apple, the cavity is filled up with brown sugar, and the apple is covered all over with a thin layer of suet crust, tied tightly into a cloth, and boiled.

British pastry is not outstandingly good, but there are certain fillings for pies and tarts which are excellent, and which are hardly to be found in other countries. Treacle tart is a delicious dish, and the large or small mince pies which are eaten especially at Christmas, but else fairly frequently at other times, are almost equally good. The mince-meat with which they are filled is a mixture of various kinds of dried fruits, chopped fine, mixed up with sugar and raw beef suet, and flavoured with brandy. Other favourite fillings are jams of various kinds, lemon curd – a preparation of lemon juice, yolk of egg and sugar – and stewed apples flavoured with lemon juice or cloves. An apple pie is often given an exceptionally fine flavour by including one quince among about half a dozen apples.

The other main category of puddings – milk puddings – is the kind of thing that one would prefer to pass over in silence, but it must be mentioned, since these dishes are, unfortunately, characteristic of Britain. They are preparations of rice, semolina, barley, sago or even macaroni, mixed with milk and sugar and baked in the oven. The one made with barley is somewhat less bad then the others: the one made with macaroni is intolerable to any civilised palate. As all of these puddings are easy to make, they tend to be a stand-by in cheap hotels, restaurants and apartment houses, and they are one of the chief reasons why British cookery has a bad name among foreign visitors.

There are, of course, XXX countless other sweet dishes, including the whole range of jellies, blancmanges, custards, soufflés, ice puddings, meringues and what-nots, which are much the same in all European counties. A few oddments which do not fit into any of the above categories are pancakes – British pancakes are thinner than those of most countries, and are always eaten with lemon juice, – batter pudding, which is made of much the same ingredients as Yorkshire pudding, but is steamed instead of being baked and is eaten with treacle, and baked apples. The apples are cored but not peeled, filled up with butter and sugar, and cooked in the oven: it is important that they should be served in the dish in which they are cooked With cooked fruit of any kind British people always eat cream, if they can get it. In the West of England a particularly delicious kind of clotted cream is made by slowly simmering large pens of milk and skimming off the cream as it comes to the surface.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)

December 10, 2019

QotD: British breakfast – “Not a snack but a serious meal”

First of all, then, breakfast. Ideally for nearly all British people, and in practice for most of them even now, this is not a snack but a serious meal. The hour at which people have their breakfast is of course governed by the time at which they go to work, but if they were free to choose, most people would like to have breakfast at nine o’clock. In principle the meal consists of three courses, one of which is a meat course. Traditionally it starts with porridge, which is made of coarse oatmeal, sodden and then boiled into a spongy mess: it is eaten always hot, with cold milk (better still, cream) poured over it, and sugar. Breakfast cereals, which are ready-cooked preparations of wheat or rice, taken cold with milk and sugar, are often eaten instead of porridge. After this comes either fish, usually salt fish, or meat in some form, or eggs in some form. The best and most characteristically British form of salt fish is the kipper, which is a herring split open and cured in wood-smoke until it is deep brown colour. Kippers are either grilled or fried. The usual breakfast meat dishes are either fried bacon, with or without fried eggs, grilled kidneys, fried pork sausages, or cold ham. British people favour a lean, mild type of bacon or ham, cured with sugar and nitre rather than with salt. At normal time it is not unusual to eat grilled beef steaks or mutton chops at breakfast, and there are still old-fashioned people who like to start the day with cold roast beef. In some parts of the country, for instance in East Anglia, it is usual to eat cheese at breakfast.

After the meat course comes bread, or more often toast, with butter and orange marmalade. It must be orange marmalade, though honey is a possible substitute. Other kinds of jam are seldom eaten at breakfast, and marmalade does not often appear at other times of [the] day. For the great bulk of British people, the invariable breakfast drink is tea. Coffee in Britain is almost always nasty, either in restaurants or in private houses; the majority of people, though they drink it fairly freely, are uninterested in it and do not know good coffee from bad. Of tea, on the other hand, they are extremely critical, and everyone has his favourite brand and his pet theory as to how it should be made. Tea is always drunk with milk, and it is usual to brew it very strong, about one spoonful of dry tea leaves being allowed for each cup. Most people prefer Indian to Chinese tea, and they like to put sugar in it. Here, however, one comes upon a class distinction, or more exactly a cultural distinction. Virtually all British working-people put sugar in their tea, and indeed will not drink tea without it. Unsweetened tea is an upper-class or middle-class habit, and even in those classes it tends to be associated with a Europeanised palate. If one made a list of the people in Britain who prefer wine to beer, one would probably find that it included most of the people who prefer tea without sugar.

After this solid breakfast – and even now, in a time of rationing, it is usual to eat a fairly large bulk of food, chiefly bread, at breakfast – it is natural that the midday meal should be somewhat lighter than it is in many other countries.

George Orwell, “British Cookery”, 1946. (Originally commissioned by the British Council, but refused by them and later published in abbreviated form.)