Whisper it gently, but there’s a mysterious woman in Boris Johnson’s life. Someone very special to him. Though she gets none of the credit, she’s the secret of his success, so it’s time she emerged from the shadows and received the recognition she deserves. Step forward … Theresa May.

Exactly two years ago, our second female Prime Minister was bowing out. After a torrid time in office it was finally over, and it ended with characteristic grace. In her resignation statement, she blamed no one for her fall, expressing only gratitude for the chance she’d had to serve the country she loved.

Her critics were not so generous. Ranked against other Prime Ministers […] she fares poorly. In particular, she suffers by comparison to her successor. He delivered Brexit; she didn’t. He won a majority; she lost one. But that’s not the whole story. Two years on from the end of her premiership, we need to tell the truth: which is that Boris owes it all to Theresa.

It wouldn’t be the first time that a successful PM is found to be in debt to a predecessor. Winston Churchill, for instance, owed a great deal to the much-maligned Neville Chamberlain. The reason why Britain was able to hold out against Hitler was that, before the war, Chamberlain had rearmed the country. In particular, he built up the fighter capacity of the RAF, which proved so crucial in the Battle of Britain.

As for Chamberlain’s infamous failures, these too were foundational to Churchill’s success. It’s unlikely that the great man would have become Prime Minister had Chamberlain not exhausted the credibility of appeasement. Indeed she did more than Chamberlain to ensure ultimate triumph of her successor, and looking beyond the obvious low points of her premiership a very different picture emerges. Indeed, she provided the key ingredients for the victories that followed.

Peter Franklin, “Boris owes it all to Theresa May”, UnHerd, 2021-05-23.

October 4, 2021

QotD: Theresa May is to Boris as Neville Chamberlain was to Winston

August 20, 2021

“They were there to debate Afghanistan, a far-away country of which it turns out that we know even less than we thought”

The British government recalls Parliament to debate the situation in Afghanistan (not that there’s much to be done at this late stage, but formalities are at least being observed in a perfunctory manner):

The House of Commons was full, for the first time since last March. Members of Parliament had been brought back from their holidays, from West Country campsites and from Greek resorts, in a repatriation operation that puts the Foreign Office to shame.

They were there to debate Afghanistan, a far-away country of which it turns out that we know even less than we thought. It was only last month that Boris Johnson was assuring MPs that “there is no military path to victory for the Taliban”, although we now know that path was straight along the road to Kabul, as fast as their trucks could carry them.

Now Johnson was back to explain that things had turned out to be a bit more complicated than he thought. Or perhaps a bit simpler: we’ve gone, they’re back. Parliament was getting eight hours to discuss this, although it was too late to do very much about it. It wasn’t so much shutting the stable door after the horse had bolted as holding a long discussion about the history of equine care as the stallion in question disappeared over the horizon.

Still, the atmosphere was jolly. Many of these MPs haven’t seen each other in over a year. There was a first-day-of-term feel to things. With Parliament’s Covid restrictions lapsed, the Conservatives were wedged in together in the small, windowless chamber, barely a facemask in sight. The government’s instructions are still to wear masks in crowded places, but the Conservatives view Covid as some sort of socialist conspiracy that will go away if they ignore it. Or maybe they just feel that rules are for the little people.

Labour MPs had at least nodded to social distancing, sitting about 18 inches apart from each other. This is, admittedly, easier when there aren’t very many of you. The opposition benches were a sea of masks. Only the Democratic Unionists, who like the Tories see illness as a sign of moral failure, were a lone island of uncovered faces.

Johnson’s statement was, as ever, a masterpiece of bare adequacy. It eloquently just about dealt with the matter in question, magisterially pretty much covering the bases. The speechwriters, one sensed, must have been working on the words late into the previous afternoon. They had gone through as many as one draft as they tried to come up with something that, if it didn’t deal with every complex nuance of the Afghan tragedy, at least asked the question that Johnson lives by: “Will this do?”

The situation in Afghanistan was a “concern”, the prime minister explained, with what might, in another context, have been a brilliantly comic understatement. Over the past 20 years, the British had worked for a better future for the people of Afghanistan. “Some of this progress,” the prime minister said, “is fragile”, which is certainly one way of putting it.

What had gone wrong with our intelligence services, several people asked, that they had so comprehensively failed to see this coming? Be fair, replied Johnson, even the Taliban had been surprised by the speed of their own advance.

On the US Naval Institute Blog, CDRSalamander notes the only speech in the House of Commons during that debate that grabbed and held the attention of the entire body:

Let’s back away from the problem at hand a bit … and then back up further. I mentioned it earlier, but let’s bring it up again; national humiliation. There are different aspects of this growing humiliation that are already manifesting itself, the first of which is how others look at us.

Let’s start with our closest friend and take a moment to listen to a speech earlier today in the British House of Commons by Tom Tugendhat, MP.

The mission in Afghanistan wasn’t a British mission, it was a Nato mission. … And so it is with great sadness that I now criticise one of them. … To see their commander-in-chief call into question the courage of men I fought with — to claim that they ran. It is shameful. … this is a harsh lesson for all of us and if we are not careful it could be a very, very difficult lesson for our allies. … to make sure we are not dependent on a single ally, on the decision of a single leader, but that we can work together with Japan and Australia, with France and Germany, with partners large and small, and make sure we hold the line together.

That is our closest friend outlining a loss of confidence. That is just one datapoint from a friend, but it is safe to say that it is probably somewhere in the center of opinion.

What are those nations who are not our friends thinking? I don’t think I need to spend all that much time on discussing how emboldened they are. It is self-evident to anyone who reads USNIBlog.

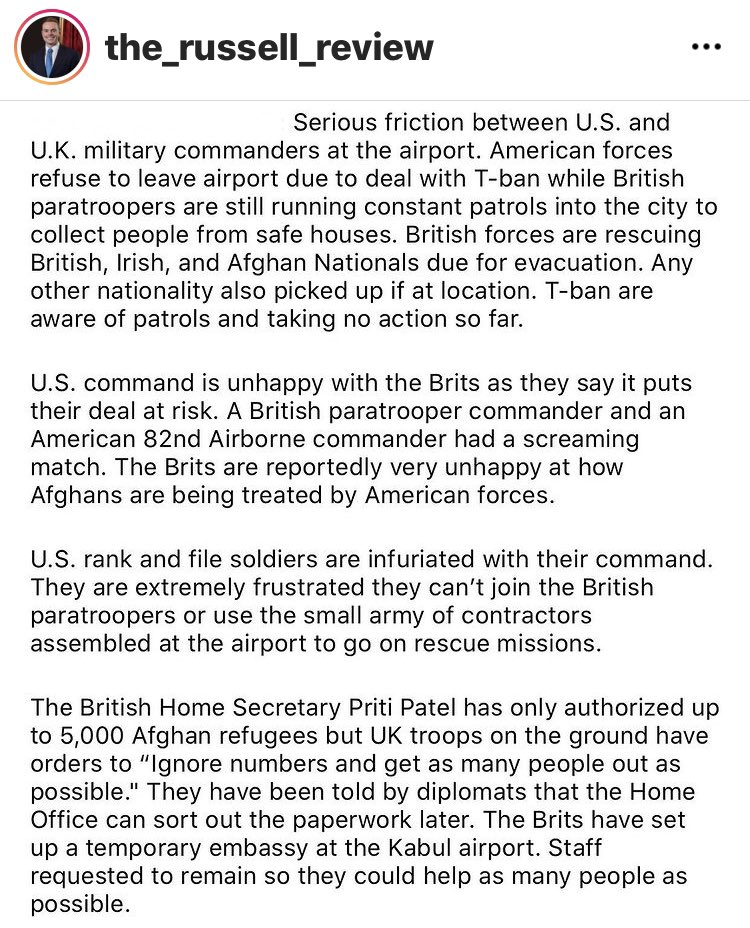

On the ground, troops of 2nd Battalion, The Parachute Regiment are actively involved in escorting British and Afghani civilians from safe houses to Kabul airport for evacuation:

At least one NATO country hasn’t forgotten the civilians who have been left behind during the precipitate withdrawal by US troops.

July 24, 2021

Boris Johnson as a character-brought-to-life from Evelyn Waugh’s Scoop

In The Critic, Robert Hutton explains why so many members of the British press find Waugh’s satire of their trade so compelling:

Boris Johnson, Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs at an informal meeting of the Foreign Affairs Council on 15 February 2018.

Photo by Velislav Nikolov via Wikimedia Commons.

For a British reporter, Scoop is the holy text of the job. One of the enduring mysteries of journalism is that a trade which employs large numbers of skilled writers, and puts them into interesting situations every day, has been the subject of so few really good novels. Scoop was written as satire, but eight decades after it was published, and after the industry has gone through two technological revolutions, it remains the best description of UK journalistic life.

While parts of the job have changed — copy is no longer filed in an abbreviated telegramese to reduce transmission costs — much remains the same. Anxious newspaper executives still live in terror of capricious proprietors. Reporters still enjoy a strange fellowship of simultaneous competition and cooperation. Entertaining readers remains as important as informing them.

So how does the current British PM fit into all of this? Well, Boris had been a journalist:

Which brings us to Boris Johnson. As well as being Britain’s most successful politician, the prime minister has long been one of the country’s highest-paid journalists, a job he did entirely in the Scoop mould. His sympathetic biographer, Andrew Gimson, describes how, posted to Brussels, Johnson delighted in producing stories that were more entertaining than accurate. It was not that he was opposed to writing accurate stories, but he didn’t see it as in any way essential.

The Scoop character Johnson most resembles isn’t the hero — Boot is too naïve, his reports too close to reality. Nor is the press corps regulars, Corker, Shumble, Whelper and Pigge, who huddle in the same hotel, lest they will be beaten on a story. Johnson, both as journalist and politician, has generally preferred to hunt alone. We must look to the man Boot replaced at the Beast, foreign correspondent Sir Jocelyn Hitchcock.

Like Johnson, who was hazy on the outcome of the Battle of Stalingrad, Sir Jocelyn is more confident than he should be about history (“He was wrong about the Battle of Hastings,” says Lord Copper. “It was 1066. I looked it up”). He hides in his hotel room before filing an entirely imaginary interview — something else for which Johnson has form. Sir Jocelyn was, pleasingly, modelled on Sir Percival Phillips, a correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, which would later employ Johnson.

Sir Jocelyn’s fabrications didn’t hold him back, and Johnson’s propelled him to the front rank of journalism, then into politics, where he exhibits the same behaviour: the pursuit of a higher “truth” unburdened by facts, the deadline mentality, the reluctance to correct mistakes, the assumption that someone else should pick up the bill. Johnson was neither the kind of journalist nor a prime minister who would read a study on, say, pandemic preparedness. A leaked document from his first months in the job showed him describing Cameron as a “girly swot” for wanting to show that MPs were hard at work.

March 25, 2021

Boris wanted to be a new Churchill, but instead is shaping up as a cut-rate Cromwell

Bella Wallersteiner on the vast difference between Boris Johnson’s hopes for his premiership and the actual role he’s been playing:

A year has passed since the British public accepted lockdown as the best way to combat the spread of the novel coronavirus, yet we are still living under the strictures of the Coronavirus Act.

In the name of virus protection, we have experienced a level of authoritarianism not seen in this country since the time of Oliver Cromwell – restrictions on freedom of movement, forced closure of businesses, and prohibitions on weddings and funerals have challenged many of our most cherished beliefs about the limits of government power, while the ban on large gatherings means we cannot even legally protest them.

Today, as we mark the anniversary of the first lockdown, we would do well to reflect on just how compliant we have become to what were intended to be “emergency” powers.

Cheery platitudes have ranged from “we’re all in this together” and “we’ll send this virus packing” to the hopelessly inaccurate “it will all be over by Christmas”. But history tells us that governments tend to hold on to additional powers far longer than is necessary.

The Defence of the Realm Act of 1914, for example, granted the government wide-ranging powers in the name of public safety, including heavy censorship of the press and the introduction of rationing. Pub licensing laws remained in place for decades, only relaxed in November 2005.

The Second World War brought The Emergency Powers (Defence) Act 1939 which ceded immense regulatory powers to the government, including provisions “for the apprehension, trial and punishment of persons offending against the Regulations and for the detentions of persons whose detention appears to be expedient to the Secretary of State in the interest of public safety or the defence of the realm”. The Act was finally repealed on 25th March 1959, but the last of the Defence Regulations (which included the maintenance of public order) was not lifted until 31st December 1964.

March 11, 2021

Boris as a latter-day Prince Rupert of the Rhine?

In The Critic, Graham Stewart portrays the British Prime Minister and Sir Keir Starmer, leader of Her Majesty’s loyal opposition in the House of Commons as English Civil War combatants:

King Charles I and Prince Rupert before the Battle of Naseby 14th June 1645 during the English Civil War.

19th century artist unknown, from Wikimedia Commons.

Prime Minister’s Questions distils into a single gladiatorial contest what thousands of enthusiasts in a charitable organisation called the Sealed Knot perform across the country most summers – namely the re-enactment of battles of the English Civil War.

Unsmiling, relentless, serious to the point of bringing despair to his foot-soldiers as much as his opponents, Sir Keir Starmer is a Roundhead general for our times. Nobody believes better than he that virtue and providence are his shield. This faith sustains him whilst the fickle and ungodly court of popular opinion fails to rally to his command. He believes that holding firm, doggedly probing the enemy with the long pike and short-sword will eventually prevail, no matter how long the march to victory may prove.

Facing him, the generous girth of the nation’s leading Cavalier occupies his command-post. His long, uncut hair resembling a thatch on a half-timbered cottage, Boris Johnson lands at the despatch box as if he has just fallen from his place of concealment in an oak tree, bleary and under-prepared, but confident in assertion. It might be said of him, as Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton once said of the parliamentary style of a previous Tory prime minister, Lord Derby, that Johnson is “irregularly great, frank, haughty, bold – the Rupert of debate.”

Today was one of those occasions when the prime minister did indeed resemble the dashing Prince Rupert of the Rhine. Unfortunately, it was the moment during the decisive civil war battle of Naseby when the great Cavalier commander charged his horsemen through the parliamentary lines with such momentum that they kept going and ended up spending the rest of the day plundering a distant baggage train rather than returning to determine the result of the battle.

January 17, 2021

Hector Drummond on Boris “Cane-Toad” Johnson

As a teaser to attract new subscribers to his Patron and SubscribeStar pages, Hector Drummond shared this piece on the ecological disaster of Australia’s 1930s cane-toad importation and the similar political disaster of Boris Johnson in Britain:

In the 1930s Queensland farmers were facing trouble with large numbers of cane beetles eating the sugar crops that were an important part of the state’s economy. So the Bureau of Sugar Experiment Stations came up with a cunning plan. They would import some cane toads (a native of middle and south America), because cane toads ate cane beetles. This was sure to solve the problem in a trice. One-hundred and two cane toads were duly imported into the state, from Hawaii as it happened, to do the job.

Unfortunately this soon became a classic case of the cure being worse than the disease. In fact it wasn’t any cure at all because the cane toads didn’t bother much with the cane beetles, and instead ate everything else they could wrap their tongues around. The other thing they did was multiply at an explosive rate. These days there are estimated to be 200 million cane toads in Australia, mainly in Queensland, and they cause havoc with the native fauna, not least because they have nasty poison-producing glands on the back of their head which the native animals have no naturally-evolved defence against. Curious pet dogs who mess about with a toad can die.

In 2019 Britain was facing its own crisis. It had become obvious to half the country that Theresa May’s Conservative government was deliberately trying to prevent Brexit from happening. As the other parties were even worse, the only hope for a real Brexit to take place was if a new pro-Brexit leadership in the Conservative party could be installed. After a titanic struggle, this finally happened, and Alexander “Boris” Johnson became the new leader, with Michael Gove and advisor Dominic Cummings at his side.

Unfortunately Johnson has proven to be Britain’s own version of the cane toad, a cure that is vastly worse than the disease. Johnson, at least, proved to be more able than his Australian counterpart at doing the job that was required of him. Whereas the Australian toad was about as interested in cane beetles as Olly Robbins was in getting the UK out of the EU, Johnson at least gave us a middling type of Brexit which, as fudged as it was, was at least far better than anything any of his fellow MPs could have got.

But in terms of being worse than the disease, Cane-Toad Johnson has proven to be far, far more destructive than the cane toad ever was. The cane toad, after all, is merely an ecological pest, whereas Johnson has proved to be a dangerous menace to the country’s liberty, prosperity and health. The poison from his glands has leached into our very life. We have become like domestic dogs who have been forced to lick them every day.

December 21, 2020

Boris “Ebenezer” Johnson cancels Christmas

What is it with British PMs and political U-turns?

So Christmas is cancelled. The neo-Cromwellian edict has been issued. The thing that Boris Johnson said would be “inhuman” just a few days ago has now been done. For the first time in centuries people in vast swathes of England – London and the South East – will be forbidden by law from celebrating Christmas together. The government’s promise of five days’ relief from the stifling, atomising, soul-destroying lockdown of everyday life has been snatched away from us. It’s too risky, the experts say; the disease will spread and cause great harm. You know what else will cause great harm? This cruel, disproportionate cancellation of Christmas; this decree against family festivities and human engagement.

This evening Boris Johnson executed the most disturbing u-turn of his premiership: he scrapped the planned relaxation of lockdown rules for Christmas. He commanded that London and the South East will be propelled into Tier 4, yet another Kafkaesque category of authoritarianism dreamt up by our increasingly technocratic rulers. This means no household mixing, including on Christmas Day. That’s millions of planned get-togethers, family celebrations, cancelled with the swipe of a bureaucrat’s pen. Other areas outside of London are luckier: Boris has graciously granted them one day off from the lockdown rules, on Christmas Day, when they may mix with people from other households. They will no doubt give praise to their benevolent protectors for such festive if fleeting charity.

There is much that is disturbing about Boris’s decree. It is being justified on the basis that a new strain of Covid-19 is spreading in the South East and seems more contagious than earlier strains. That is certainly something we should be aware of. But Boris also declared that there is no evidence that this new strain has led to “increased mortality”. So what is going on here? Surely before enacting the drastic, almost unprecedented measure of preventing millions of people from celebrating Christmas together the government should offer up clearer evidence of the significant social harms that would allegedly spring from such celebrations? The political and media elites go on and on about “evidence-based policy”, except when it comes to locking people down. Then it’s all “Yeh, go ahead, better safe than sorry”.

October 6, 2020

Has Boris had his fifteen minutes yet?

James Delingpole is very much of the opinion that Boris Johnson’s time is almost up and is starting to consider who would replace him as British PM:

Prime Minister Boris Johnson at his first Cabinet meeting in Downing Street, 25 July 2019.

Official photograph via Wikimedia Commons.

It’s no longer a question of “if” but when the ailing, flailing UK Prime Minister crashes and burns. The only remaining questions now are “How much more damage is the buffoon going to inflict before he retires, gracefully or otherwise?” and “Who is going to pick up the pieces when he is gone?”

With the second question, my money is on Chancellor Rishi Sunak. Sure he’s a young-ish (40), fairly untested, partly unknown quantity and, perhaps worse, he’s a graduate of Goldman Sachs. On the other hand, with no General Election likely till 2024, it’s a simple fact that whoever replaces Johnson as prime minister will almost certainly be a member of his current cabinet. Sunak scores highly because he’s arguably the senior minister least tainted by Johnson’s spectacular mishandling of Chinese coronavirus.

Unlike Johnson, his preening Health Secretary Matt Hancock, and Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster Michael Gove, Sunak is not one of the so-called “Doves” advocating for ever more stringent measures — lockdowns, masks, curfews, quarantines, a mooted cancellation of Christmas.

Rather, he is the leader of the Hawk faction arguing that it is long since time to prioritise the economy.

True, opinion polls currently favour the Doves — aka the Bedwetters. The British public has so far proved remarkably amenable to having its freedoms snatched away in order to keep it “safe” from coronavirus. Polls continue to suggest that the vast majority of British people want more authoritarian measures, not fewer, in order to deal with the crisis. And Dominic Cummings — the sinister, opinion-poll-driven schemer who, as Johnson’s chief advisor has been controlling the Prime Minister much in the manner of Wormtongue controlling King Théoden in Lord of the Rings — has been more than happy to oblige.

But it would be a massive error to assume that this state of affairs will last.

October 3, 2020

“The Tory party, desirous of a fat majority, will sell the country out over Europe”

In The Critic, Gawain Towler sees a major opportunity for Nigel Farage and the Brexit Party:

The simple fact is that this Government had the opportunity to do something about our negotiations with the EU in the months after the election. They had a whopping great majority and the goodwill of the nation. Boris had used his ebullience to present the country with a vision that with one bound we would be free, the deal was oven-ready, he was going to get Brexit done. Yes, he had inherited the Withdrawal Agreement, a deeply duff deal, from his predecessor. His resignation as Foreign Secretary over it gave us the confidence that he recognised it as such. And yet on the 25 January, a mere month after his triumphant election victory, he signed that same duff deal and condemned the country to this slow lingering betrayal. It was not necessary to do so, he could have pointed to the election, the vote, and with the support of the country gone to Brussels and made it clear he would not sign. This he signally failed to do.

So here we are again, with the EU making threatening noises, taking legal action with leaks coming out of Berlin and London suggesting that the UK is prepared to make more concessions. A No 10 spokesman confirmed that “The PM will be speaking to President von der Leyen tomorrow afternoon to take stock of negotiations and discuss next steps.”

According to Bruno Waterfield of The Times, “This is seen broadly as a good sign – if, as expected, the British prime minister is ready to signal a bit more give on fish, state aid and subsidy control”.

Note the “more give” – there has already been a lot of giving.

The thing is that Boris is beset with problems, with the Remain lobby, both on his own green benchers and elsewhere; yet again digging up dire predictions of economic meltdown, the CBI taking the lead. The ERG group of Tory sceptics have been oddly quiet, focusing more on Covid-19 than on the clear danger of a failed Brexit. There is no pressure on one side, and a great tidal wave of it pushing him to make a deal at any cost.

Then there is the electoral arithmetic. This shouldn’t matter so far out from an election, but the rumours of Boris’s political demise and the currents swirling around the Chancellor make Labour’s slight lead in the polls a matter of concern. Labour is beginning to solidify after years of infighting, but it is not cutting into Tory support.

That is where Nigel Farage and the Brexit Party come in.

September 24, 2020

I thought we were supposed to speak well of the (politically) dead

In The Critic, Nigel Jones examines the soon-to-be-published “political tittle-tattle” of the wife of an MP and junior cabinet minister during David “Dave” Cameron’s premiership:

For anyone who has been holidaying under a rock for the past fortnight and may have missed the furore, I should explain that Lady Swire, daughter of Mrs Thatcher’s former Defence Secretary Sir John Nott, is the wife of ex-Tory MP Sir Hugo Swire, an Old Etonian chum of David Cameron, who somehow failed to be promoted beyond the ranks of junior ministers during his pal’s Premiership, but remained a close confidante and boon holiday companion to the PM. Lady Swire herself is half-Slovenian, and though brought up in the bosom of the Tory establishment, may not be entirely attuned to the evasions, hypocrisy and double standards that make up British political life, which makes her book all the more enjoyable.

Throughout Dave’s inglorious time in office, Lady Swire kept a secret diary detailing intimacies of conversation, banter and badinage, and revealing insights that give – shall we say – a not wholly flattering picture of the ruling Tory clique at play during their most unguarded moments. The bad behaviour, petty jealousies and embarrassing remarks of Dave, George, Boris and Michael and their wives are set down in all their toe-curling cringeworthiness.

The diaries are to be published next week but have been serialised in The Times and reviewed and widely commented on in the rest of the media. The two main targets – the duopoly of Cameron and Osborne – have already expressed their displeasure at the revelations. But all the tut-tutting disapproval of Lady Swire’s profitable indiscretions misses the main point: there is nothing that the British public relishes and enjoys more than an exposé of their leaders with their dignity gone and their metaphorical trousers down.

Moreover, gossip and tittle tattle as set down in diaries often tells us more about the true nature of politics and the motivations and personalities of politicians than a thousand self-serving pompous political memoirs or dull works of dry political analysis. What we really want is gossip – the gamier the better – and all the inconvenient truths our rulers rather we didn’t know.

Very often what we learn from particular epochs of history are the telling anecdotes and juicy titbits revealed by diarists rather than the respectability that the statesmen themselves wish to present and be remembered for. Our picture of the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, for example, and the very merry court of Charles II, along with the apocalyptic disasters of fire and plague that followed comes largely from the indiscreet journals of Samuel Pepys, Daniel Defoe, and John Evelyn.

September 12, 2020

“‘Lovable’ Boris Johnson is currently presiding over the biggest assault on the British people’s freedoms since Cromwell’s Commonwealth”

James Delingpole has had it with Boris Johnson’s proto-fascist approach to dealing with the Wuhan Coronavirus:

… ask yourself how you’d have felt a year ago — or even six months ago — if you’d been told a British government was planning to institute a 10pm curfew, ban gatherings of more than six people, impose daily immunity tests before you were allowed to go about your business, employ Stasi-like volunteer “marshals” to ensure public compliance and warning that it might even have to cancel Christmas?

Your first reaction would have been: “Impossible. This is the kind of thing that excitable foreigners engage in. Never the phlegmatic, rational British – and certainly, never, ever, EVER so long as there’s a Conservative government in power.”

Your second reaction would have been: “Oh, I get it. It’s a joke, right? You’re telling me the plotline of some new dystopian graphic novel on the lines of Watchmen currently being adapted for Amazon Prime or Netflix, yeah?”

I still can’t quite believe it myself.

[…]

It’s possible that Boris’’s brush with death earlier this year — his excessive weight, unfortunately, put him in the Covid at-risk category — may have stolen his mojo and left him a dried-out husk entirely unfit for public office.

Or it may just be that Boris was always going to be exposed for the chancer he is, sooner or later: all that was needed was the crisis which would cruelly reveal just how useless he is — at least where statesmanship is concerned — at rising to the occasion.

Either way, “lovable” Boris Johnson is currently presiding over the biggest assault on the British people’s freedoms since Cromwell’s Commonwealth (which was the last occasion on which Christmas was more or less banned).

But maybe the most shocking part of the tyranny Boris is currently imposing on Britain is the lack of justification for it.

If Covid-19 really were a version, say, of the Black Death — which wiped out 60 per cent of Europe’s population — most of us would probably agree to sacrifice our freedoms in order to reduce the risk of dying in agony with pustulous buboes while vomiting black blood. Back in the 14th century, there might possibly have been a place for a Boris Johnson, or a Matt Hancock or a Chris Whitty — and if only someone could build a time machine, sharpish, maybe we could facilitate this.

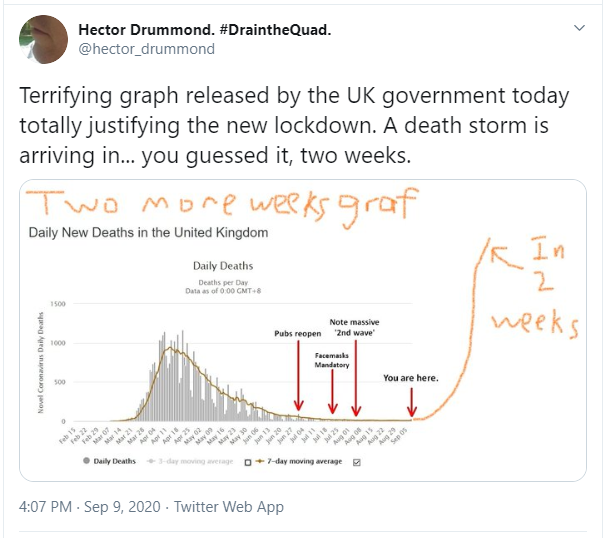

And if that wasn’t enough, check out this graph!

August 29, 2020

Recreating British Railways?

Adrian Quine looks at the long-term results of the partial privatization of British Railways, and the current British government’s options to address some of the problems:

Wikimedia caption – “This is the Bring Back British Rail, a reverse image of the old BR logo, (now used by the TOC’s) to show we are heading the wrong way with Rail in the UK”

If there is one thing free marketeers and large state socialists agree on, it would be the terrible state/private hybrid ownership structure of our railways currently supported by the government. While large state socialists won’t be happy until the private sector is squeezed out of the system, market liberals view the Conservative government’s actions as creeping renationalisation.

The private-sector entrepreneurs that built many of Britain’s railways in the 19th century had – through a process of market discovery – settled on vertical integration, with the same firm owning the track and operating the trains. But, when railways were returned to private sector in the late 1990s, the government created one national infrastructure company (Railtrack), 25 train-operating companies (TOCs), 3 freight operating companies, 3 rolling-stock leasing companies, 13 infrastructure service companies and other support organisations. The Office of Passenger Rail Franchising was tasked with selling franchises to the TOCs, while the Office of the Rail Regulator (ORR) regulated the infrastructure. This artificial and fragmented structure was designed to give the impression of competition.

Despite these constraints, in the early days of John Major’s flawed privatisation some of the more enterprising private train operators managed to bring innovation to the sector, including improved marketing and very low-cost “yield managed” advance fares. Where allowed, competition between different operators brought improved customer service, additional direct trains and lower ticket prices. However, the flaws in the initial privatisation soon became apparent with failed franchises leading to increased government intervention and renationalisation by subsequent governments.

While attempts were made to downplay the significance of July’s decision by the Office of National Statistics to put train operators on the public balance sheet, it is in fact only the latest in a worrying string of signals about the direction in which the railway and Boris Johnson’s government are headed. In June, the transport secretary Grant Shapps announced to a parliamentary select committee plans to introduce concessions across the rail network. Private operators will simply be paid a set fee to provide a basic service – another nail in the coffin for commercial investment or innovation.

Attention is now turning to what the government will do when the current “Emergency Measures Agreements” – hastily put in place to ensure trains kept running when passenger numbers nosedived by 95% as lockdown began – comes to an end in September.

June 30, 2020

May 8, 2020

The Wuhan Coronavirus lockdown – “perhaps the worst policy mistake ever committed by Western governments during peacetime”

Toby Young on the fall of “Professor Lockdown”, the former top advisor to the British government on the response to the Wuhan Coronavirus epidemic:

The reason for looking into the political affiliations of the scientists and experts who’ve been advising governments across the world during this crisis is that it may throw some light on why those governments have made such poor policy decisions. Will the vast majority of those advisers turn out to be left-of-centre, like Professor Ferguson? I’m 99% sure of it, and I think that will help us to understand what’s happened.

I don’t mean they’ve deliberately given right-of-centre governments poor advice in the hope of wrecking their economies for nefarious party political reasons or because they’re members of Extinction Rebellion and want to destroy capitalism. Nor do I believe in any of the conspiracy theories linking these public health panjandrums to Bill Gates and Big Pharma and some diabolical plan to vaccinate 7.8 billion people. I have little doubt they’ve acted in good faith throughout – and that’s part of the problem. The road they’ve led us down has been paved with all the usual good intentions.

The mistakes these liberal policy-makers have made are depressingly familiar to anyone who’s studied the breed: overestimating the ability of the state to solve complicated problems as well as the capacity of state-run agencies to deliver on those solutions; failing to anticipate the unintended consequences of large-scale state interventions; thinking about public policy in terms of moral absolutes rather than trade-offs; chronic fiscal incontinence, with zero inhibitions about adding to the national debt; not trusting in the common sense of ordinary people and believing the only way to get them to avoid risky behaviour is to put strict rules in place and threaten them with fines or imprisonment if they disobey them (and ignoring those rules themselves, obviously); arrogantly assuming that anyone who challenges their policy preferences is either ignorant or evil; never venturing outside their metropolitan echo chambers; citizens of anywhere rather than somewhere… you know the rest. We’ve seen it a hundred times before.

More often than not, the “solutions” these left-leaning experts come up with make the problems they’re grappling with even worse, and so it will prove to be in this case. The evidence mounts on a daily basis that locking down whole populations in the hope of “flattening the curve” was a catastrophic error, perhaps the worst policy mistake ever committed by Western governments during peacetime. Just yesterday we learnt that the lockdowns have forced countries across the world to shut down TB treatment programmes which, over the next five years, could lead to 6.3 million additional cases of TB and 1.4 million deaths. There are so many stories like this it’s impossible to keep track. We will soon be able to say with something approaching certainty that the cure has been worse than the disease.