Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Sept 2025Japanese bayonets followed the same trend of simplification as Arisaka rifles towards the end of World War Two, culminating in what is today called the “pole bayonet”. Abandoning even the fittings to mount to a rifle, these bayonets were intended to be lashed to a pole to create a spear. The Japanese government did not have the military forces to repulse an American invasion of the home islands, and was actively planning to sacrifice millions of Japanese civilians in a hopeless defense, literally having them charge American machine guns with spears. Some of this was done on outer island battles, like Saipan and Okinawa but the scale in Japan itself would have been unimaginable. It was the nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that led to a Japanese surrender and prevented this from becoming a reality.

(more…)

January 30, 2026

Japanese Last-Ditch Pole Spear Bayonet

December 26, 2025

The Pinnacle of Movie ⚔️Swordfights⚔️

Jill Bearup

Published 8 Sept 2025Scaramouche had, until recently, the longest swordfight in cinema history. It’s still regarded as one of the best. Why? Let’s talk about it.

December 16, 2025

QotD: Arms and the (pre-modern) man (at arms)

… how much value might a heavily armored fighter or warrior be carrying around on their backs in the real world? Because I think the answer here is informative.

Here we do have some significant price data, but of course its tricky to be able to correlate a given value for arms and armor with something concrete like wages in every period, because of course prices are not stable. But here are some of the data points I’ve encountered:

We don’t have good Roman price data from the Republic or early/high Empire, unfortunately (and indeed, the reason I have been collecting late antique and medieval comparanda is to use it to understand the structure of earlier Roman costs). Hugh Elton1 notes that a law of Valens (r. 364-378) assessed the cost of clothing, equipment and such for a new infantry recruit to be 6 solidi and for a cavalryman, 13 solidi (the extra 7 being for the horse). The solidus was a 4.5g gold coin at the time (roughly equal to the earlier aureus) so that is a substantial expense to kit out an individual soldier. For comparison, the annual rations for soldiers in the same period seem to have been 4-5 solidi, so we might suggest a Roman soldier is wearing something like a year’s worth of living expenses.2

We don’t see a huge change in the Early Middle Ages either. The seventh century Lex Ripuaria,3 quotes the following prices for military equipment: 12 solidi for a coat of mail, 6 solidi for a metal helmet, 7 for a sword with its scabbard, 6 for mail leggings, 2 solidi for a lance and shield for a rider (wood is cheap!); a warhorse was 12 solidi, whereas a whole damn cow was just 3 solidi. On the one hand, the armor for this rider has gotten somewhat more extensive – mail leggings (chausses) were a new thing (the Romans didn’t have them) – but clearly the price of metal equipment here is higher: equipping a mailed infantryman would have some to something like 25ish solidi compared to 12 for the warhorse (so 2x the cost of the horse) compared to the near 1-to-1 armor-to-horse price from Valens. I should note, however, warhorses even compared to other goods, show high volatility in the medieval price data.

As we get further one, we get more and more price data. Verbruggen (op. cit. 170-1) also notes prices for the equipment of the heavy infantry militia of Bruges in 1304; the average price of the heavy infantry equipment was a staggering £21, with the priciest item by far being the required body armor (still a coat of mail) coming in between £10 and £15. Now you will recall the continental livre by this point is hardly the Carolingian unit (or the English one), but the £21 here would have represented something around two-thirds of a year’s wages for a skilled artisan.

Almost contemporary in English, we have some data from Yorkshire.4 Villages had to supply a certain number of infantrymen for military service and around 1300, the cost to equip them was 5 shillings per man, as unarmored light infantry. When Edward II (r. 1307-1327) demanded quite minimally armored men (a metal helmet and a textile padded jack or gambeson), the cost jumped four-fold to £1, which ended up causing the experiment in recruiting heavier infantry this way to fail. And I should note, a gambeson and a helmet is hardly very heavy infantry!

For comparison, in the same period an English longbowman out on campaign was paid just 2d per day, so that £1 of kit would have represented 120 days wages. By contrast, the average cost of a good quality longbow in the same period was just 1s, 6d, which the longbowman could earn back in just over a week.5 Once again: wood is cheap, metal is expensive.

Finally, we have the prices from our ever-handy Medieval Price List and its sources. We see quite a range in this price data, both in that we see truly elite pieces of armor (gilt armor for a prince at £340, a full set of Milanese 15th century plate at more than £8, etc) and its tricky to use these figures too without taking careful note of the year and checking the source citation to figure out which region’s currency we’re using. One other thing to note here that comes out clearly: plate cuirasses are often quite a bit cheaper than the mail armor (or mail voiders) they’re worn over, though hardly cheap. Still, full sets of armor ranging from single to low-double digit livres and pounds seem standard and we already know from last week’s exercise that a single livre or pound is likely reflecting a pretty big chunk of money, potentially close to a year’s wage for a regular worker.

So while your heavily armored knight or man-at-arms or Roman legionary was, of course, not walking around with the Great Pyramid’s worth of labor-value on his back, even the “standard” equipment for a heavy infantryman or heavy cavalryman – not counting the horse! – might represent a year or even years of a regular workers’ wages. On the flipside, for societies that could afford it, heavy infantry was worth it: putting heavy, armored infantry in contact with light infantry in pre-gunpowder warfare generally produces horrific one-sided slaughters. But relatively few societies could afford it: the Romans are very unusual for either ancient or medieval European societies in that they deploy large numbers of armored heavy infantry (predominately in mail in any period, although in the empire we also see scale and the famed lorica segmentata), a topic that forms a pretty substantial part of my upcoming book, Of Arms and Men, which I will miss no opportunity to plug over the next however long it takes to come out.6 Obviously armored heavy cavalry is even harder to get and generally restricted to simply putting a society’s aristocracy on the battlefield, since the Big Men can afford both the horses and the armor.

But the other thing I want to note here is the social gap this sort of difference in value creates. As noted above with the bowman’s wages, it would take a year or even years of wages for a regular light soldier (or civilian laborers of his class) to put together enough money to purchase the sort of equipment required to serve as a soldier of higher status (who also gets higher pay). Of course it isn’t as simple as, “work as a bowman for a year and then buy some armor”, because nearly all of that pay the longbowman is getting is being absorbed by food and living expenses. The result is that the high cost of equipment means that for many of these men, the social gap between them and either an unmounted man-at-arms or the mounted knight is economically unbridgeable.7

Bret Devereaux, “Fireside Friday, January 10, 2025”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2025-01-10.

- Warfare in Roman Europe AD 350-425 (1996), 122.

- If you are wondering why I’m not comparing to wages, the answer is that by this point, Roman military wages are super irregular, consisting mostly of donatives – special disbursements at the accession of a new emperor or a successful military campaign – rather than regular pay, making it really hard to do a direct comparison.

- Here my citation is not from the text directly, but Verbruggen, The Art of War in Western Europe during the Middle Ages (1997), 23.

- From Prestwich, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages (1996).

- These prices via Hardy, Longbow: A Social and Military History (1992).

- Expect it no earlier than late this year; as I write this, the core text is actually done (but needs revising), but that’s hardly the end of the publication process.

- Man-at-arms is one of those annoyingly plastic terms which is used to mean “a man of non-knightly status, equipped in the sort of kit a knight would have”, which sometimes implies heavy armored non-noble infantry and sometimes implies non-knightly heavy cavalry retainers of knights and other nobles.

December 3, 2025

August 28, 2025

A civil society can’t allow young Scottish hellions to brandish weapons at immigrants harassing them

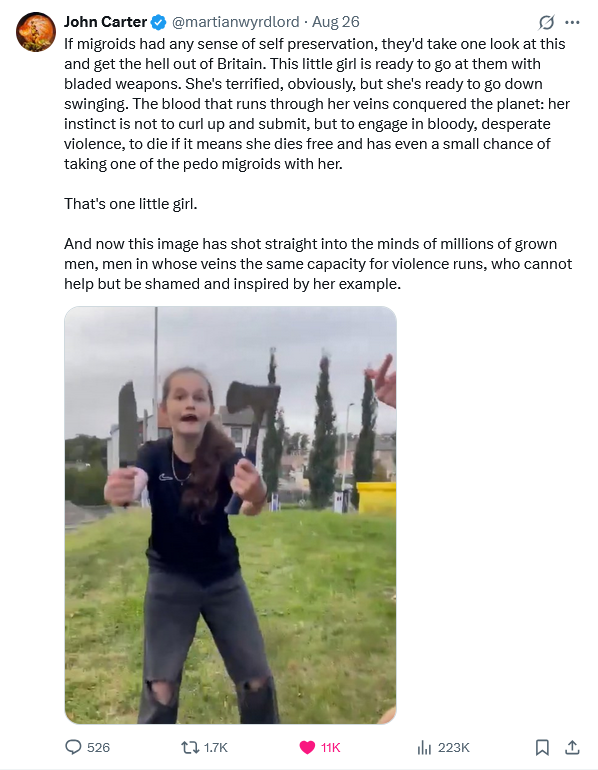

At least, the headline expresses how the sky people probably frame the situation where a young girl felt she needed to scare off a threat to herself and her friend. This is from an X post which claims to be describing what actually happened rather than what the media has been reporting:

I spoke with the mom of one of the girls (Mayah) and got the entire story that the media is covering up and lying about.

So first of all, the reporting got the names of the girls mixed up. There were 3 girls who were there who were accosted and attacked by the migrants.

Lola – Lola is the hero from the video. She’s the one with the axe defending her sister from the migrant attackers

Ruby – Lola’s older sister who was attacked and hospitalized

Mayah – Ruby’s best friend who was with them and went to call the police after Ruby was attacked by the migrants

Here’s the summary of what happened from Mayah’s mother:

“Yes. So what happened was the girls where out just walking and the man in the picture made comments to lola(the younger girl) calling her sexy and other sexual remarks then the girls started to tell this man to leave them alone and stop following them and making sexual remarks to them. After that the man’s sister (also in the picture) came around the corner and physically attacked ruby(the older sister) she grabbed her hair dragged her to the floor started to punch her then both the man and woman where kicking her in head while she was on the floor. At this point my daughter (mayah) called the police so my daughters account after that is all abit blurry. But that is when lola had the weapons she pulled them out to protect ruby. After that the man came back at lola recording her making sure she showed the weapons to the camera and antagonising her. Ruby was hospitalised after the attack with a severe concussion a tennis ball sized lump to the back of her head aswell as lots of bruises.”

John Carter reacts to the original image, also on X:

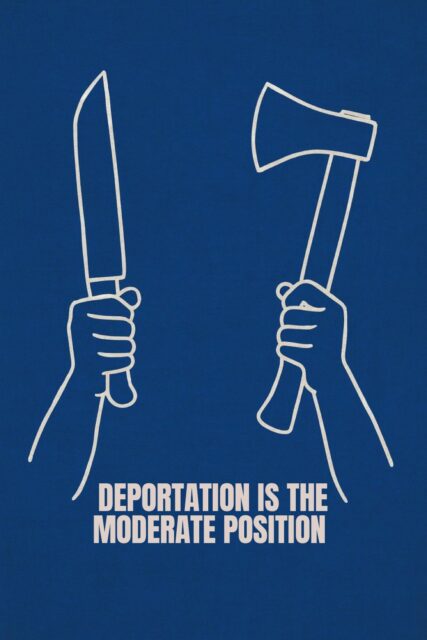

This should be a turning point, but god knows how many such the British elites have ignored so far. Another graphic from X expresses what may happen if this is also ignored:

Even the Brits can be pushed too far and we can’t be very far from that point now. And the way the British media is handling this and pretty much every other confrontation is not helping:

You can’t have missed her, if you’re on social media at all, the dual-wielding 14-year-old Scottish lass raising two blades in defiance of the “migrant” seemingly intent on assaulting her and her 12-year-old friend.

The name of this hero won’t be released due to her age, and police were right on the scene to arrest the violent attacker.

That’s right: the little girl is in jail, charged with possession of a bladed weapon. Two weapons, actually — what appear to be a large santoku-style blade and a small hatchet.

In the widely-circulated clip, her would-be attacker (with the non-British accent) can be heard taunting her to show the blades on camera. Why? The answer is obvious: he’s well aware that self-defense is illegal in Britain, and he also knows she’ll be the one the cops take away.

And he was correct on both counts.

[…]

Culturally, things are so crazy that the BBC didn’t just blur out our heroine’s face, they even blurred out her blades. And now you understand the screencap at the top of this column. Mustn’t ruffle any feathers, you see.

How about pepper spray and the like? Sorry, mate, but pepper spray was banned as a “prohibited weapon” (!!!) in 1968.

In Britain, the only legal defense against rape is a whistle — which is to say, no defense at all.

That 14-year-old girl found it necessary to possibly defend herself and her friend against two possible assailants: would-be rapists and the British criminal justice system. The day came, and she proved herself a hero.

She warded off the former, but God only knows what indignities she’ll suffer at the hands of the latter.

What’s the next little British girl’s defense against that?

June 11, 2025

QotD: “Pike and Shot” in the early gunpowder era

… this is why the pike[-armed infantry] fought in squares: it was assumed the cavalry was mobile enough to strike a group of pikemen from any direction and to whirl around in the empty spaces between pike formations, so a given pike square had to be able to face its weapons out in any direction or, indeed, all directions at once.

Instead, pike and shot were combined into a single unit. The “standard” form of this was the tercio, the Spanish organizational form of pike and shot and one which was imitated by many others. In the early 16th century, the standard organization of a tercio – at least notionally, as these units were almost never at full strength – was 2,400 pikemen and 600 arquebusiers. In battle, the tercio itself was the maneuver unit, moving as a single formation (albeit with changing shape); they were often deployed in threes (thus the name “tercio” meaning “a third”) with two positioned forward and the third behind and between, allowing them to support each other. The normal arrangement for a tercio was a “bastioned square” with a “sleeve of shot”: the pikes formed a square at the center, which was surrounded by a thin “sleeve” of muskets, then at each corner of the sleeve there was an additional, smaller square of shot. Placing those secondary squares (the “bastions” – named after the fortification element) on the corner allowed each one a wide potential range of fire and would mean that any enemy approaching the square would be under fire at minimum from one side of the sleeve and two of the bastions.

That said, if drilled properly, the formation could respond dynamically to changing conditions. Shot might be thrown forward to provide volley-fire if there was no imminent threat of an enemy advance, or it might be moved back to shelter behind the square if there was. If cavalry approached, the square might be hollowed and the shot brought inside to protect it from being overrun by cavalry. In the 1600s, against other pike-and-shot formations, it became more common to arrange the formation linearly, with the pike square in the center with a thin sleeve of shot while most of the shot was deployed in two large blocks to its right and left, firing in “countermarch” (each man firing and moving to the rear to reload) in order to bring the full potential firepower of the formation to bear.

Indeed it is worth expanding on that point: volley fire. The great limitation for firearms (and to a lesser extent crossbows) was the combination of frontage and reloading time: the limited frontage of a unit restricted how many men could shoot at once (but too wide a unit was vulnerable and hard to control) and long reload times meant long gaps between shots. The solution was synchronized volley fire allowing part of a unit to be reloading while another part fired. In China, this seems to have been first used with crossbows, but in Europe it really only catches on with muskets – we see early experiments with volley fire in the late 1500s, with the version that “catches on” being proposed by William Louis of Nassau-Dillenburg (1560-1620) to Maurice of Nassau (1567-1625) in 1594; the “countermarch” as it came to be known ends up associated with Maurice. Initially, the formation was six ranks deep but as reloading speed and drill improved, it could be made thinner without a break in firing, eventually leading to 18th century fire-by-rank drills with three ranks (though by this time these were opposed by drills where the first three ranks – the front kneeling, the back slightly offset – would all fire at once but with different sections of the line firing at different times (“fire-by-platoon”)).

Coming back to Total War, the irony is that while the basic components of pike-and-shot warfare exist in both Empire: Total War and for the Empire faction in Total War: Warhammer, in both games it isn’t really possible to actually do pike-and-shot warfare. Even if an army combines pikes and muskets, the unit sizes make the kind of fine maneuvers required of a pike-and-shot formation impossible and while it is possible to have missile units automatically retreat from contact, it is not possible to have them pointedly retreat into a pike unit (even though in Empire, it was possible to form hollow squares, a formation developed for this very purpose).

Indeed if anything the Total War series has been moving away from the gameplay elements which would be necessary to make representing this kind of synchronized discipline and careful formation fighting possible. While earlier Total War games experimented with synchronized discipline in the form of volley-fire drills (e.g. fire by rank), that feature was essentially abandoned after Total War: Shogun 2‘s Fall of the Samurai DLC in 2012. Instead of firing by rank, musket units in Total War: Warhammer are just permitted to fire through other members of their unit to allow all of the soldiers in a formation – regardless of depth or width – to fire (they cannot fire through other friendly units, however). That’s actually a striking and frustrating simplification: volley fire drills and indeed everything about subsequent linear firearm warfare was focused on efficient ways to allow more men to be actively firing at once; that complexity is simply abandoned in the current generation of Total War games.

Bret Devereaux, “Collection: Total War‘s Missing Infantry-Type”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2022-04-01.

April 24, 2025

QotD: The Phalanx

… we need to distinguish what sort of phalanx because this is not the older hoplite phalanx in two very important ways: first, it is equipped and fights differently, but second it has a very different place in the overall tactical system: the Macedonian phalanx may be the “backbone” of a Hellenistic army, but it is not the decisive arm of the system.

So let’s start with the equipment, formation and fighting style. The older hoplite phalanx was a shield wall, using the large, c. 90cm diameter aspis and a one-handed thrusting spear, the dory. Only the front rank in a formation like this engaged the enemy, with the rear ranks providing replacements should the front hoplites fall as well as a morale force of cohesion by their presence which allowed the formation to hold up under the intense mental stress of combat. But while hoplites notionally covered each other with their shields, they were mostly engaged in what were basically a series of individual combats. As we noted with our bit on shield walls, the spacing here seems to have been wide enough that while the aspis of your neighbor is protecting you in that it occupies physical space that enemy weapons cannot pass through, you are not necessarily hunkered down shoulder-to-shoulder hiding behind your neighbor’s shield.

The Macedonian or sarisa-phalanx evolves out of this type of combat, but ends up quite different indeed. And this is the point where what should be a sentence or two is going to turn into a long section. The easy version of this section goes like this: the standard Macedonian phalangite (that is, the soldier in the phalanx) carried a sarisa, a two-handed, 5.8m long (about 19ft) pike, along with an aspis, a round shield of c. 75cm carried with an arm and neck strap, a sword as a backup weapon, a helmet and a tube-and-yoke cuirass, probably made out of textile. Officers, who stood in the first rank (the hegemones) wore heavier armor, probably consisting of either a muscle cuirass or a metal reinforced (that is, it has metal scales over parts of it) tube-and-yoke cuirass. I am actually quite confident that sentence is basically right, but I’m going to have to explain every part of it, because in popular treatments, many outdated reconstructions of all of this equipment survive which are wrong. Bear witness, for instance, to the Wikipedia article on the sarisa which gets nearly all of this wrong.

Wikipedia‘s article on the topic as of January, 2024. Let me point out the errors here.

1) The wrong wood, the correct wood is probably ash, not cornel – the one thing Connolly gets wrong on this weapon (but Sekunda, op. cit. gets right).

2) The wrong weight, entirely too heavy. The correct weight should be around 4kg, as Connolly shows.

3) Butt-spikes were not exclusively in bronze. The Vergina/Aigai spike is iron, though the Newcastle butt is bronze (but provenance, ????)

4) They could be anchored in the ground to stop cavalry. This pike is 5.8m long, its balance point (c. 1.6m from the back) held at waist height (c. 1m), so it would be angled up at something like 40 degrees, so anchoring the butt in the ground puts the head of the sarisa some 3.7m (12 feet) in the air – a might bit too high, I may suggest. The point could be brought down substantially if the man was kneeling, which might be workable. More to the point, the only source that suggests this is Lucian, a second century AD satirist (Dial Mort. 27), writing two centuries after this weapon and its formation had ceased to exist; skepticism is advised.

5) We’ll get to shield size, but assuming they all used the 60cm shield is wrong.

6) As noted, I don’t think these weapons were ever used in two parts joined by a tube and also the tube at Vergina/Aigai was in iron. Andronikos is really clear here, it is a talon en fer and a douille en fer. Not sure how that gets messed up.Sigh. So in detail we must go. Let us begin with the sarisa (or sarissa; Greek uses both spellings). This was the primary weapon of the phalanx, a long pike rather than the hoplite‘s one-handed spear (the dory). And we must discuss its structure, including length, because this is a case where a lot of the information in public-facing work on this is based on outdated scholarship, compounded by the fact that the initial reconstructions of the weapon, done by Minor Markle and Manolis Andronikos, were both entirely unworkable and, I think, quite clearly wrong. The key works to actually read are the articles by Peter Connolly and Nicholas Sekunda.1 If you are seeing things which are not working from Connolly and Sekunda, you may safely discard them.

Let’s start with length; one sees a very wide range of lengths for the sarisa, based in part on the ancient sources. Theophrastus (early third century BC) says it was 12 cubits long, Polybius (mid-second century) says it was 14 cubits, while Asclepiodotus (first century AD) says the shortest were 10 cubits, while Polyaenus (second century AD) says that the length was 16 cubits in the late fourth century.2 Two concerns come up immediately: the first is that the last two sources wrote long after no one was using this weapon and as a result are deeply suspect, whereas Theophrastus and Polybius saw it in use. However, the general progression of 12 to 14 to 16 – even though Polyaenus’ word on this point is almost worthless – has led to the suggestion that the sarisa got longer over time, often paired to notions that the Macedonian phalanx became less flexible. That naturally leads into the second question, “how much is a cubit?” which you will recall from our shield-wall article. Connolly, I think, has this clearly right: Polybius is using a military double-cubit that is arms-length (c. 417mm for a single cubit, 834mm for the double), while Theophrastus is certainly using the Athenian cubit (487mm), which means Theophrastus’ sarisa is 5.8m long and Polybius’ sarisa is … 5.8m long. The sarisa isn’t getting longer, these two fellows have given us the same measurement in slightly different units. This shaft is then tapered, thinner to the tip, thicker to the butt, to handle the weight; Connolly physically reconstructed these, armed a pike troupe with them, and had the weapon perform as described in the sources, which I why I am so definitively confident he is right. The end product is not the horribly heavy 6-8kg reconstructions of older scholars, but a manageable (but still quite heavy) c. 4kg weapon.

Of all of the things, the one thing we know for certain about the sarisa is that it worked.

Next are the metal components. Here the problem is that Manolis Andronikos, the archaeologist who discovered what remains our only complete set of sarisa-components in the Macedonian royal tombs at Vergina/Aigai managed to misidentify almost every single component (and then poor Minor Markle spent ages trying to figure out how to make the weapon work with the wrong bits in the wrong place; poor fellow). The tip of the weapon is actually tiny, an iron tip made with a hollow mid-ridge massing just 100g, because it is at the end of a very long lever and so must be very light, while the butt of the weapon is a large flanged iron butt (0.8-1.1kg) that provides a counter-weight. Finally, Andronikos proposed that a metal sleeve roughly 20cm in length might have been used to join two halves of wood, allowing the sarisa to be broken down for transport or storage; this subsequently gets reported as fact. But no ancient source reports this about the weapon and no ancient artwork shows a sarisa with a metal sleeve in the middle (and we have a decent amount of ancient artwork with sarisae in them), so I think not.3

Polybius is clear how the weapon was used, being held four cubits (c. 1.6m) from the rear (to provide balance), the points of the first five ranks could project beyond the front man, providing a lethal forward hedge of pike-points.4 As Connolly noted in his tests, while raised, you can maneuver quite well with this weapon, but once the tips are leveled down, the formation cannot readily turn, though it can advance. Connolly noted he was able to get a English Civil War re-enactment group, Sir Thomas Glemham’s Regiment of the Sealed Knot Society, not merely to do basic maneuvers but “after advancing in formation they broke into a run and charged”. This is not necessarily a laboriously slow formation – once the sarisae are leveled, it cannot turn, but it can move forward at speed.

The shield used by these formations is a modified form of the old hoplite aspis, a round, somewhat dished shield with a wooden core, generally faced in bronze.5 Whereas the hoplite aspis was around 90cm in diameter, the shield of the sarisa-phalanx was smaller. Greek tends to use two words for round shields, aspis and pelte, the former being bigger and the latter being smaller, but they shift over time in confusing ways, leading to mistakes like the one in the Wikipedia snippet above. In the classical period, the aspis was the large hoplite shield, while the pelte was the smaller shield of light, skirmishing troops (peltastai, “peltast troops”). In the Hellenistic period, it is clear that the shield of the sarisa-phalanx is called an “aspis” – these troops are leukaspides, chalkaspides, argyraspides (“white shields”, “bronze shields”, “silver shields” – note the aspides, pl. of aspis in there). This aspis is modestly smaller than the hoplite aspis, around 75cm or so in diameter; that’s still quite big, but not as big.

Then we have some elite units from this period which get called peltastai but have almost nothing to do with classical period peltastai. Those older peltasts were javelin-equipped light infantry skirmishers. But Hellenistic peltastai seem to be elite units within the phalanx who might carry the sarisa (but perhaps a shorter one) and use a smaller shield which gets called the pelte but is not the pelte of the classical period. Instead, it is built exactly like the Hellenistic aspis – complete with a strap-suspension system suspending it from the shoulder – but is smaller, only around 65cm in diameter. These sarisa-armed peltastai are a bit of a puzzle, though Asclepiodotus (1.2) in describing an ideal Hellenistic army notes that these guys are supposed to be heavier than “light” (psiloi) troops, but lighter than the main phalanx, carrying a smaller shield and a shorter sarisa, so we might understand them as an elite force of infantry perhaps intended to have a bit more mobility than the main body, but still be able to fight in a sarisa-phalanx. They may also have had less body-armor, contributing that the role as elite “medium” infantry with more mobility.6

Finally, our phalangites are armored, though how much and with what becomes really tricky, fast. We have an inscription from Amphipolis7 setting out military regulations for the Antigonid army which notes fines for failure to have the right equipment and requires officers (hegemones, these men would stand in the front rank in fighting formation) to wear either a thorax or a hemithorakion, and for regular soldiers where we might expect body armor, it specifies a kottybos. All of these words have tricky interpretations. A thorax is chest armor (literally just “a chest”), most often somewhat rigid armor like a muscle cuirass in bronze or a linothorax in textile (which we generally think means the tube-and-yoke cuirass), but the word is sometimes used of mail as well.8 A hemithorakion is clearly a half-thorax, but what that means is unclear; we have no ancient evidence for the kind of front-plate without back-plate configuration we get in the Middle Ages, so it probably isn’t that. And we just straight up don’t know what a kottybos is, although the etymology seems to suggest some sort of leather or textile object.9

In practice there are basically two working reconstructions out of that evidence. The “heavy” reconstruction10 assumes that what is meant by kottybos is a tube-and-yoke cuirass, and thus the thorax and hemithorakion must mean a muscle cuirass and a metal-reinforced tube-and-yoke cuirass respectively. So you have a metal-armored front line (but not entirely muscle cuirasses by any means) and a tube-and-yoke armored back set of ranks. I would argue the representational evidence tends to favor this; we most often see phalangites associated with tube-and-yoke cuirasses, rarely with muscle cuirasses (but sometimes!) and not often at all in situations where they have the rest of their battle kit (helmet, shield, sarisa) as required for the regular infantry by the inscription but no armor.

Then there is the “light” reconstruction11 which instead reads this to mean that only the front rank had any body armor at all and the back ranks only had what amounted to thick travel cloaks. Somewhat ironically, it would be really convenient for the arguments I make in scholarly venues if Sekunda was right about this … but I honestly don’t think he is. My judgment rebels against the notion that these formations were almost entirely unarmored and I think our other evidence cuts against it.12

Still, even if we take the “heavy” reconstruction here, when it comes to armor, we’re a touch less well armored compared to that older hoplite phalanx. The textile tube-and-yoke cuirass, as far as we can tell, was the cost-cutting “cheap” armor option for hoplites (as compared to more expensive bell- and later muscle-cuirasses in bronze). That actually dovetails with helmets: Hellenistic helmets are lighter and offer less coverage than Archaic and Classical helmets do as well. Now that’s by no means a light formation; the tube-and-yoke cuirass still offers good protection (though scholars currently differ on how to reconstruct it in terms of materials). But of course all of this makes sense: we don’t need to be as heavily armored, because we have our formation.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Phalanx’s Twilight, Legion’s Triumph, Part Ia: Heirs of Alexander”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2024-01-19.

1. So to be clear, that means the useful is P. Connolly, “Experiments with the sarissa” JRMES 11 (2000) and N. Sekunda, “The Sarissa” Acta Universitatis Lodziensis 23 (2001). The parade of outdated scholarship is Andronikos, “Sarissa” BCH 94 (1970); M. Markle, “The Macedonian sarissa” AJA 81 (1977) and “Macedonian arms and tactics” in Macedonia and Greece in Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Times, (1982), P.A. Manti, “The sarissa of the Macedonian infantry” Ancient World 23.2 (1992) and “The Macedonian sarissa again” Ancient World 25.2 (1994), J.R. Mixter, “The length of the Macedonian sarissa” Ancient World 23.2 (1992). These weren’t, to be clear, bad articles, but they are stages of development in our understanding, which are now past.

2. Theophrastus HP 3.12.2. Polyb. 18.29.2. Asclepiodotus Tact. 5.1; Polyaenus Strat. 2.29.2. Also Leo Tact. 6.39 and Aelian Tact. 14.2 use Polybius’ figure, probably quoting him.

3. Also, what very great fool wants his primary weapon, which is – again – a 5.8m long pike that masses around 4kg to be held together in combat entirely by the tension and friction of a c. 20cm metal sleeve?

4. Christopher Matthew, op. cit., argues that Polybius must be wrong because if the weapon is gripped four cubits from the rear, it will foul the rank behind. I find this objection unconvincing because, as noted above and below, Peter Connolly did field drills with a pike troupe using the weapon and it worked. Also, we should be slow to doubt Polybius who probably saw the weapon and its fighting system first hand.

5. What follows is drawn from K. Liampi, Makedonische Schild (1998), which is the best sustained study of Hellenistic period shields.

6. Sekunda reconstructs them this way, without body armor, in Macedonian Armies after Alexander, (2013). I think that’s plausible, but not certain.

7. Greek text is in Hatzopoulos, op. cit.

8. Polyb. 30.25.2. Also of scale, Hdt. 9.22, Paus. 1.21.6.

9. The derivation assumed to be from κοσύμβη or κόσσυμβος, which are a sort of shepherd’s heavy cloak.

10. Favored by Hatzopoulos, Everson and Connolly.

11. Favored by Sekunda and older scholarship, as well as E. Borza, In the Shadow of Olympus (1990), 204-5, 298-9.

12. Representational evidence, but also the report that when Alexander got fresh armor for his army, he burned 25,000 sets of old, worn out armor. Curtius 9.3.21; Diodorus 17.95.4. Alexander does not have 25,000 hegemones, this must be the armor of the general soldiery and if he’s burning it, it must be made of organic materials. I think the correct reading here is that Alexander’s soldiers mostly wore textile tube-and-yoke cuirasses.

March 31, 2025

Berettas With Bayonets: The Very Early Model 38A SMG

Forgotten Weapons

Published 29 Nov 2024The initial model of the Beretta 38A had a number of features that were dropped rather quickly once wartime production became a priority. Specifically, they included a lockout safety switch for just the rear full-auto trigger. This was in place primarily for police use, in which the guns were intended for semiautomatic use except on dire emergency (and the first batches of 38As in Italy went to the police and the Polizia dell’Africa Italiana). The first version of the 38A also included a bayonet lug to use a version of the folding bayonet also used on the Carcano rifles. This was a folding-blade bayonet, and the model for the 38A replaced the rifle muzzle ring with a special T-lug to attach to the muzzle brake of the SMG. These bayonets are extremely scarce today, as they were only used for a very limited time.

(more…)

January 28, 2025

What Britain desperately needs is common-sense pointy stick controls

Britain’s gun laws make Canada look like the wild west, yet the government still wants far greater control over objects that can be used as weapons. The conviction of the Southport murderer, who used a knife obtained through Amazon, seems to have given the British government under Kurt Stürmer Keir Starmer an excuse to crack down even further on any kind of device with a sharpened blade rather than the criminals who wield them:

“Time and again, as a child, the Southport murderer carried knives. Time and again, he showed clear intent to use them,” U.K. Prime Minister Keir Starmer wrote in a piece for The Sun about Axel Rudakubana, who admitted murdering three girls and injuring others at a Taylor Swift-themed dance class last year. “And yet tragically, he was still able to order the murder weapon off of the internet without any checks or barriers. A two-click killer. This cannot continue. The technology is there to set up age-verification checks, even for kitchen knives ordered online.”

What Starmer mentioned but glossed over is that Rudakubana was three times referred to a program intended to divert people from radicalization and terrorism before authorities lost interest in him. At the time of his arrest, he had a copy of an Al Qaeda training manual, which led him to being charged and sentenced for terrorism. He also possessed the deadly poison ricin that he’d manufactured himself in sufficient quantity to conduct a mass attack.

Rudakubana was a human bomb waiting to go off. But Starmer focused not on officials’ failure to pay attention, but on knives — edged tools that are among humans’ earliest and most important creations.

“Online retailers will be required to ask for two types of ID from anyone seeking to buy a knife under plans being considered by ministers to combat under-age sales after the Southport murders,” reports Charles Hymas of The Telegraph. “Buyers would have to submit an ID document to an online retailer and then record a live video or selfie to prove their age.”

It’s difficult to see how an ID check is going to stand between those planning mayhem and tools first crafted 2.6 million years ago in their most primitive form and still used by people every day. My dentist forges knives in his backyard for fun. One of my nephews turns files into knives on a grinding wheel. Scraping an appropriate material against a stone will give you an edge and a point. ID checks don’t seem like a barrier to people with bad intentions and the ability to make ricin in their bedrooms.

A Case History in Ridiculously Restrictive Policies

This is why the U.K. strikes many Americans as the reductio ad absurdum of policies that demonize objects rather than targeting bad actors. Opponents of authoritarian laws ask: What will the authorities do once they’ve made firearms difficult to legally acquire, and crime continues? Will they ban knives?

The answer from the U.K., which already has restrictive gun laws, is yes, they will ban knives — or at least impose access and carry restrictions and consider forbidding blades to have points. The result has been a black market in smuggled and illicitly manufactured firearms that will inevitably extend to knives. Harmless people are now arrested for having Swiss Army knives in car glove compartment or for possessing locking knives on the way home from jobs that require them. And the country’s crime problems continue to grow.

That’s bad enough, but U.K. authorities, like those elsewhere, also prefer to surveil the entire population to detect anything they could call a danger to public order, rather than focusing on specific individuals harming others.

“There are now said to be over 5.2 million CCTV cameras in the UK,” according to Politics.co.uk. “Surveillance footage forms a key component of UK crime prevention strategy,” but “the proliferation of CCTV in public places has fueled unease about the erosion of civil liberties and individual human rights, raising concerns of an Orwellian ‘big brother’ culture.”

The British government also monitors online activity to an extent that Edward Snowden deemed it “the most extreme surveillance in the history of western democracy.”

That surveillance turns up comments, jokes, and rants authorities just don’t like. “Think before you post,” the government warns people. “Content that incites violence or hatred isn’t just harmful – it can be illegal.” But the authorities enforce a broad definition of unacceptable material. People have been arrested for dressing as terrorists for Halloween, for making intemperate online remarks, and for just getting things wrong when posting on the internet (they’ll need a big paddy wagon for that one).

January 25, 2025

The stabbings will continue until morale improves

Sebastian Wang discusses the stabbing attacks in Southport, Merseyside last year:

On the 29th July 2024, a man went on a stabbing spree in Southport, Merseyside, killing three children and injuring ten others. The attacker, Axel Muganwa Rudakubana, the son of Rwandan immigrants, was arrested at the scene. By all accounts, the attack was shocking not only in its savagery, but in its attendant circumstances. Witnesses report that Mr Rudakubana shouted slogans as he killed that suggested he was an Islamic terrorist. Almost at once, social media was filled with questions and with speculation. Also, protests began in several northern cities – Manchester, Leeds, and Bradford, for example – where demonstrators blamed the Government and the ruling class for immigration policies that had made the killings both possible and likely.

Instead of considering these protests and promising to address the causes of the crime, the British Government and the legacy media focussed on managing the narrative and silencing comment on the immigration policies that had allowed Mr Rudakubana’s family into the country. Keir Starmer, the new Prime Minister, seemed more worried about potential “violence against Muslims” than the actual brutality of Mr Rudakubana’s attack on English people. “For the Muslim community I will take every step possible to keep you safe,” he said in his first public statement on the killings. On the protests he added: “It is not protesting, it is not legitimate, it is crime. We will put a stop to it“. His focus was not on the victims, but on ensuring that no one questioned the system that had allowed this to happen.

In the days after the attack, several men were arrested for spreading what the government called “misinformation” online. Their crime? Posting details about Mr Rudakubana’s background and motivations — details that turned out to be broadly correct. Despite being right, these men were prosecuted and imprisoned under Britain’s hate speech laws. The most recently convicted, Andrew McIntyre, was sentenced earlier this month to seven and a half years in prison for postings on social media. Peter Lynch, a man of 61, was sent to prison last August for two years and eight months for the crime of shouting “scum” and “child killers” at the police. Last October, he hanged himself in prison. I am told he was seriously “mistreated” in prison. British prisons for many years have been overcrowded. Room was found for these prisoners of conscience after the Government began releasing violent criminals.

The injustice of this is glaring. These men were punished not because they lied, but because they spoke approximate truths the government wanted to suppress. Their imprisonment sends a clear message: in modern Britain, it’s better to be wrong on the side of the Government than right and against it.

A Carefully Managed Narrative

The media played its part in the cover up. At first, Mr Rudakubana was described, without name, as “originally from Cardiff“. It took days before we were told he was a child of asylum seekers from Rwanda. Even then, the coverage was carefully balanced by a picture of him as a respectable schoolboy – not at the beast in human form shown by more recent photographs.

Only much later, when the story had faded from the headlines, did the real facts emerge. Mr Rudakubana was not just a troubled individual. His phone contained materials linked to terrorism and genocide, and his actions appeared to have an ideological motivation. Yet by the time these details came out, they barely caused a ripple. The public had been moved on to the next distraction.

It’s hard not to assume that the British media was fully in on gaslighting the public about the accused murderer, when you compare the photo that almost universally was used in the time before the trial and a more recent image:

Say what you like about Axel Rudakubana, the slaughterer of three English girls under ten years old, but — unlike the British Prime Minister, the Home Secretary, the Liverpool Police and most of the court eunuchs in the UK media — he appears to be an honest man:

It’s a good thing those children are dead … I am so glad … I am so happy.

He has always been entirely upfront about such things, telephoning Britain’s so-called “Childline” and asking them:

What should I do if I want to kill somebody?

Judging from his many interactions with “the authorities” (including with the laughably misnamed “Prevent” programme), the British state’s response boiled down to: Go right ahead!

It seems likely that the perpetrator of Wednesday’s Diversity Stabbing of the Day — the Afghan “asylum seeker” who killed a two-year-old boy and seriously wounded other infants in the Bavarian town of Aschaffenburg — is also “so happy”. Like Mr Rudakubana, the “asylum seeker” deliberately targeted a gathering of the very young — in this case, a kindergarten group playing in a municipal park. Like Mr Rudakubana, the “asylum seeker” did not just deliver sufficient stab wounds to kill: he plunged his knife into each target dozens and dozens of times. Like Mr Rudakubana, the “asylum seeker” was well known to the authorities: he had been detained for “violence” at least thrice.

Did these guys also enjoy it? From our pal Leilani Dowding:

For the benefit of American readers, being stabbed in Asda, Argus and Sainsbury’s is like being stabbed in Kroger, Costco and Wegman’s. As you may recall, a DC jury awarded climate mullah Michael E Mann a million bucks because someone unknown gave him a mean look in Wegman’s supermarket. No one stabbed in a UK supermarket will get a seven-figure sum: it’s increasingly a routine feature of daily life — per Sir Sadiq Khan, part of what it means to live in a great world city.

Sir Keir Stürmer and every outpost of the corrupt British state have lied to the public about every aspect of the Southport mass murder since the very first statements by the Liverpool chief constable passing off the killer as a “Cardiff man”. Her officers knew within hours that the Welsh boyo who loved male-voice choirs was, back in the real world, an observant Muslim in possession of the Al-Qaeda handbook and enough ricin to kill twelve thousand of his fellow Welshmen. But they did not disclose this information for months — not until freeborn Britons minded to disagree with Keir Stürmer’s Official Lies by suggesting that this seemed pretty obviously merely the umpteenth case of Islamostabbing had been rounded up, fast-tracked through Keir’s kangaroo courts, gaoled for longer than Muslim child rapists, and in at least one case driven to his death. Does Sir Keir feel bad about the late Peter Lynch? Or does he take the same relaxed attitude to his victims as Axel Rudakubana?

It’s a good thing that that far-right extremist is dead … I am so glad … I am so happy.

Even now, six months on, the organs of the state are still lying — although, with all the previous lies being no longer operative, Stürmer & Co have had the wit to introduce a few new ones. For example:

‘A total disgrace’ that Southport killer could buy a knife on Amazon aged 17, says Cooper

That would be Yvette Cooper, the Home Secretary — which is the equivalent of what Continental governments usually call the Minister of the Interior, because that’s where the knives penetrate.

October 16, 2024

Roman Historian Rates 10 Ancient Rome Battles In Movies And TV | How Real Is It? | Insider

Insider

Published Jun 18, 2024Historian Michael Taylor rates depictions of ancient Rome in Gladiator, Spartacus, and Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny.

(more…)

September 17, 2024

Parisian Needlefire Knife-Pistol Combination

Forgotten Weapons

Published Nov 30, 2017Combination knife/gun weapons have been popular gadgets for literally hundreds of years, and this is one of the nicest examples I have yet seen. This sort of thing is usually very flimsy, and not particularly well made. This one, however, has a blade which locks in place securely and would seem to be quite practical. The firearm part is also unique, in that it uses a needlefire bolt-action mechanism. This is a tiny copy of the French military Chassepot system, complete with intact needle and obturator.

And, of course, since it is French the trigger is a corkscrew.

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.bbtv.com/collections/forg…

September 11, 2024

⚔️Parry! ⚔️Parry! 🗡️Thrust! 🗡️Thrust! GOOD!

Jill Bearup

Published Jun 3, 2024They’re MEN. They’re men in TIGHTS (tight tights!) Please enjoy the extended edition of this video with many random digressions that will mostly be cut for the public version 😀

00:00 Robin Hood: Men in Tights

00:50 The Plot, It Goeth Thusly

03:03 Prince of Thieves/Men in Tights/Maid Marian and Her Merry Men

04:50 What kind of fight do you like?

06:19 Setup for the ending fight

07:03 The Prince of Thieves fight

07:38 The Adventures of Robin Hood fight

07:53 FIGHT!

08:53 My favourite thing (compare and contrast)

10:03 The first phrase

10:39 The second phrase

11:24 The third phrase

11:43 The fourth phrase

12:29 The fifth phrase

12:40 and FIN

13:13 I love it, I really do

14:17 Book chat

15:52 Men hitting each other with sticks

17:40 Matching vibes

18:46 Just Stab Me Now audiobook update

(more…)

September 3, 2024

Second Amendment case involving switchblades in Massachusetts

J.D. Tuccille summarizes a (surprising) court decision in Massachusetts which struck down a state law banning switchblade knives:

“IMGA0174_tijuana” by gregor_y is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution undisputedly protects the individual right to own and carry firearms for self-defense, sport, and other uses. But the amendment actually says nothing about guns; it refers to “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms”, of which firearms are just one example of what dictionaries define as “a means (such as a weapon) of offense or defense”. In Massachusetts, last week, that resulted in a decision by the state’s highest court striking down a law against switchblade knives.

Protected by the Second Amendment

“We conclude switchblades are not ‘dangerous and unusual’ weapons falling outside the protection of the Second Amendment,” wrote Justice Serge Georges Jr. for the court in an opinion in Commonwealth v. Canjura that drew heavily on two landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases: Bruen (2022) and Heller (2008). The decision found the state’s ban on switchblade knives unconstitutional and dismissed charges against the defendant.

The case involved a 2020 dispute between David E. Canjura and his girlfriend, during which Boston police officers found a switchblade knife on Canjura while searching him. As is often noted, “everything is illegal in Massachusetts” and “a switch knife, or any knife having an automatic spring release device” is only one of a long list of weapons proscribed under state law. Canjura was accordingly charged.

Such absolute prohibitions on arms aren’t permitted in the wake of the Heller decision, so Canjura and his public defender, Kaitlyn Gerber, challenged the ban on switchblades, citing the federal decisions. They also relied on Jorge Ramirez v. Commonwealth (2018) in which the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court overturned a similar prohibition on stun guns on Second Amendment grounds.

“We now conclude that stun guns are ‘arms’ within the protection of the Second Amendment. Therefore, under the Second Amendment, the possession of stun guns may be regulated, but not absolutely banned,” the court found in that case.

Canjura required similar analysis based on the same earlier decisions, this time with Ramirez in the mix.

The Second Amendment Protects All “Bearable Arms”

Citing Heller, Justice Georges pointed out, “the Second Amendment extends, prima facie, to all instruments that constitute bearable arms, even those that were not in existence at the time of the founding”. Importantly, though, knives and other bladed weapons have a long history, extending back well before the birth of the country.

“A review of the history of the American colonies reveals that knives were ubiquitous among colonists, who used them to defend their lives, obtain or produce food, and fashion articles from raw materials,” commented Georges. Folding knives, in particular, grew in popularity to the point they became “almost universal”. The court saw no significant difference between the many types of folding knives used over the centuries and spring-assisted varieties developed somewhat more recently, finding “the most apt historical analogue of a modern-day switchblade is the folding pocketknife”.

September 2, 2024

Roman auxiliaries – what was their role in the Imperial Roman army?

Adrian Goldsworthy. Historian and Novelist

Published May 8, 2024The non citizen soldiers of the Roman Auxilia served alongside the Roman citizens of the legions. In the second and third centuries AD, there were at least as many auxiliaries as there were legionaries — probably more. Some were cavalry or archers, so served in roles that complemented the close order infantry of the legions. Yet the majority were infantrymen, wearing helmet and body armour. They looked different from the legionaries, but was their tactical role and style of fighting also different. Today we look at the tactical role of Roman auxiliaries.

Extra reading:

I mention M. Bishop & J. Coulston, Roman Military Equipment which is one of the best starting places. Mike Bishop’s Osprey books on specific types of Roman army equipment are also excellent. Peter Connolly’s books, notably Greece and Rome at War, also remain well worthwhile.