European Space Agency fails to harpoon a comet … successfully lands anyway:

In 1998, the Hollywood blockbuster Armageddon asked us to believe that it was possible to land a spacecraft on an asteroid hurtling towards Earth — too far-fetched, right? Not so. Today humanity just achieved the seemingly impossible.

Earlier this afternoon, scientists from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta mission successfully landed the unmanned Philae lander module on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The complexities of this mission are such that a short article cannot do justice to the men and women who made this mission a success, but here are a few of the mind-boggling highlights:

The Rosetta probe launched in March 2004 after years of careful planning. Since then, it has travelled 6.4 billion kilometres through the solar system to get into the orbit of the comet 67p, which itself is just four kilometres in diameter. Comet 67p is orbiting the Sun at speeds of up to 135,000 kilometres per hour and is currently about 500 million kilometres from Earth. After a period during which it successfully orbited comet 67p, the 100 kilogram Philae lander then separated from the Rosetta orbiter, descended slowly and landed safely.

At the time of writing, the latest reports from the ESA suggest there may have been some problems with the lander’s anchoring mechanism. The lander was designed to fire harpoons into the surface of the comet to ensure it stayed in place — this may not have worked. But to be fair, no one has tried harpooning a comet before, so a few glitches are understandable.

Update: BBC News has more on the unexpectedly bumpy landing and the risk that the lander may not be able to stay active very long due to battery limitations. Having landed in the shadow of a cliff, the batteries are not able to be recharged by the solar panels.

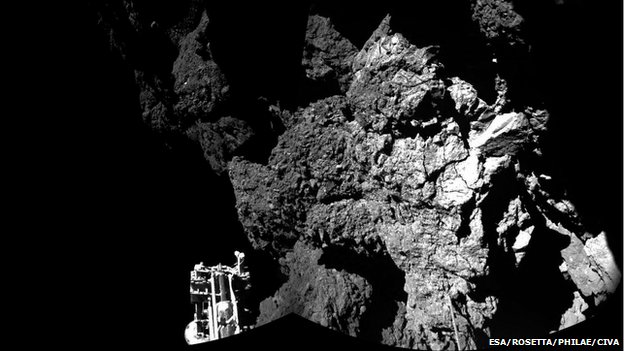

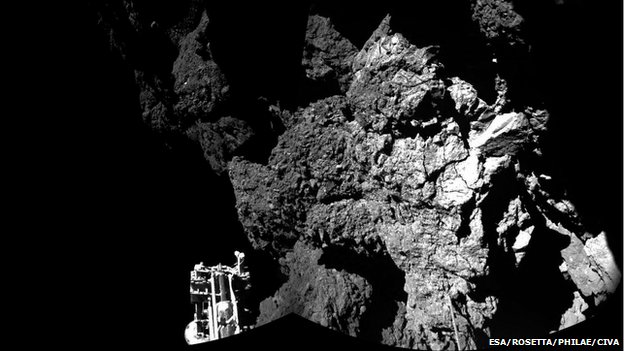

The craggy surface of the comet – looking over one of Philae’s feet

After two bounces, the first one about 1km back out into space, the lander settled in the shadow of a cliff, 1km from its target site.

It may be problematic to get enough sunlight to charge its batteries.

Launched in 2004, the European Space Agency (Esa) mission hopes to learn about the origins of our Solar System.

It has already sent back the first images ever taken on the surface of a comet.

Esa’s Rosetta satellite carried Philae on a 10-year, 6.4 billion-km (4bn-mile) journey to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which reached its climax on Wednesday.

After showing an image that indicates Philae’s location — on the far side of a large crater that was considered but rejected as a landing site — the head of the lander team Dr Stefan Ulamec said: “We could be somewhere in the rim of this crater, which could explain this bizarre… orientation that you have seen.”

Figuring out the orientation and location is a difficult task, he said.

“I can’t really give you much more than you interpret yourself from looking at these beautiful images.”

But the team is continuing to receive “great data” from several different instruments on board Philae.

Another problem with the lander — aside from not knowing exactly where it landed — is that one of the landing legs isn’t actually in contact with the surface:

Controllers re-established radio communication with the probe on cue on Thursday after a scheduled break, and began pulling of the new pictures.

These show the feet of the lander and the wider cometscape. One of the three feet is not in contact with the ground.

Philae is stable now, but there is still concern about the longer-term situation because the probe is not properly anchored — the harpoons that should have hooked it into the surface did not fire on contact. Neither did its feet screws get any purchase.

Lander project manager Stephan Ulamec told the BBC that he was very wary of now commanding the harpoons to fire, as this could throw Philae back off into space.

He also has worries about drilling into the comet to get samples for analysis because this too could affect the overall stability of the lander.

“We are still not anchored,” he said. “We are sitting with the weight of the lander somehow on the comet. We are pretty sure where we landed the first time, and then we made quite a leap. Some people say it is in the order of 1 km high.

“And then we had another small leap, and now we are sitting there, and transmitting, and everything else is something we have to start understanding and keep interpreting.”

Photo of the comet’s surface from about 40 metres as the lander made its initial descent.