Listening to Jen Gerson and Matt Gurney on The Line podcast a few days ago, I was surprised to hear that the Ontario Progressive Conservatives seem to be trying to actively torpedo the federal Conservative election campaign. While internecine combat among conservative factions is pretty normal, it isn’t quite as normal for it to be happening in the middle of a federal election campaign. It’s almost as if Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s team would rather throw the election to the Liberals than to let Pierre Poilievre’s team score a win. Some friction, sure, but this level of conflict is almost unheard of.

At Acceptable Views, Alexander Brown mulls the chatter he’s been hearing from the campaign trail:

“Something’s really going on here,” says word from on the ground in once-Liberal-safe Toronto.

“The polls say one thing, but we’ve never given out so many signs. We’ve had to print thousands more than usual.”

“We’re actually doing just fine,” says another source high up on the federal campaign trail.

“Don’t believe the chatter from disgruntled so-called conservatives … Nobody here is hanging up their skates. We’ve had a very good week — long days notwithstanding! — and are beginning to inflict solid brand damage on Carney.”

“The best is yet to come. We are running the campaign we should be running. One that’s true to conservative values and principles.”

On that “chatter”, this non-profit campaigner and writer has no qualms about going weapons-hot.

For those unaware, Ford-“conservative” insiders in Ontario have been taking to the media circuit, issuing complaint after complaint, as both anonymous and named sources, in an effort to pull the Conservatives off of major pocketbook issues such as immigration, housing, affordability, and crime, and on to, all but exclusively, Trump, Trump, Trump.

It matters to them not, apparently, that the Liberals have lucked into booby-trapping both sides of the Trump issue, and that it forces the Conservatives onto uneven terrain.

Drag this out and make it worse, as Carney has largely chosen to do? His elbows are up!

Get shoved around by the administration to the south? See, this is why he’s the one to deal with it. He’s Trump’s enemy!

(Apparently, it also matters not that Carney has received repeated pats on the head and quasi-endorsements from #45, and now, #47.)

The real story here? Allegedly embittered that they were left out of the war-room for reasons of not being all that conservative and being untrustworthy (a point they are now proving over and over again), and wanting to neglect a youth vote they were incapable of turning out, a select few in an Ontario crew think they know best, and would rather engage in public displays of industrial sabotage than keep it private and above the belt.

It’s a ridiculous little consultant slap-fight, at a time when 5000 people are standing out in the rain, to tell a man they don’t know that their Canadian Dream is now a nightmare, that they’re now drowning in debt and don’t feel hope for the future.

“These guys have no idea what they’re talking about. When this is all over, I hope they regret ever weighing in like this.”

For Doug Ford’s campaign manager Kory Teneycke, who has been working the Liberal podcast and media circuit the hardest, it might be worth noting that not every campaign has the advantage — nor indulgence — of being able to run on Liberal-lite and solely Trump.

The Ontario PCs were granted the easy road of being able to cut the corner to the polls in February, in an election no one asked for, while running Carney-adjacent messaging, and they still couldn’t pick up a seat against the worst Ontario Liberal leader of a generation.

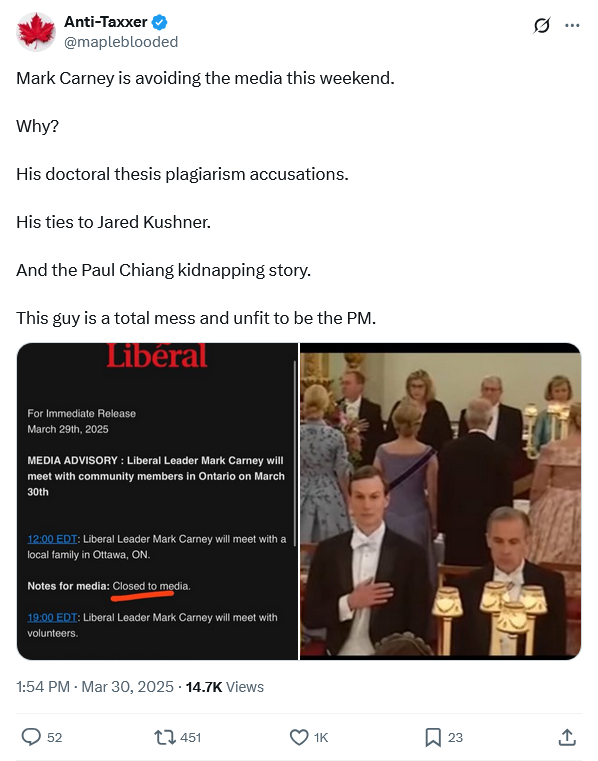

The Line‘s Gerson and Gurney both seem quite taken with the attacks on Poilievre by Ford’s right-hand spokes-hatchetman, but others are reporting lots of enthusiasm on the campaign trail and contrasting it with Carney’s handlers deliberately keeping the PM away from the press as much as they can.

The numbers of people who show up to political events isn’t a dependable metric, but if the disproportion gets to the point that you’re able to hand-count the number of supporters at a given venue, it might be a useful bit of anecdata: