Theophilus Chilton updates a review from several years ago with a few minor changes:

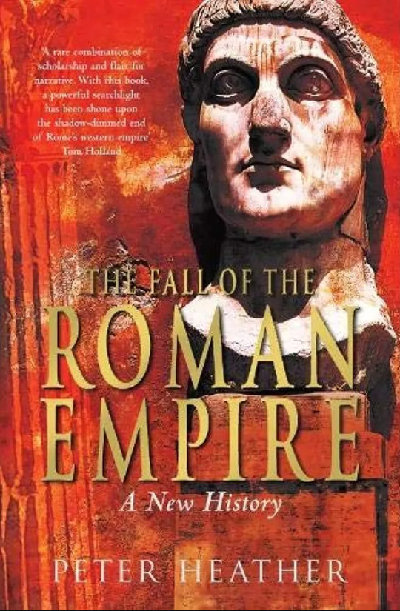

British archaeologist and historian Bryan Ward-Perkin’s excellent 2005 work The Fall of Rome and the End of Civilization is a text that is designed to be a corrective for the type of bad academic trends that seem to entrench themselves in even the most innocuous of subjects. In this case, Ward-Perkins, along with fellow Oxfordian Peter Heather in his book The Fall of the Roman Empire: A New History of Rome and the Barbarians, sets out to fix a glaring error which has come to dominate much of the scholarly study of the 4th and 5th centuries in the western Empire for the past few decades.

This error is the view that the western Empire did not actually “fall”. Instead, so say many latter-day historical revisionists, what happened between the Gothic victory at Adrianople in 378 AD and the abdication of Romulus Augustulus, the last western Emperor, in 476 was more of an accident, an unintended consequence of a few boisterous but well-meaning neighbors getting a bit out of hand. Challenged is the very notion that the Germanic tribes (who cannot be termed “barbarians” any longer) actually “invaded”. Certainly, these immigrants did not cause harm to the western Empire — for the western empire wasn’t actually “destroyed”, but merely “transitioned” seamlessly into the era we term the Middle Ages. Ward-Perkins cites one American scholar who goes so far as to term the resettlement of Germans onto land that formerly belonged to Italians, Hispanians, Britons, and Gallo-Romans as taking place “in a natural, organic, and generally eirenic manner”. Certainly, it is gauche among many modern academics in this field to maintain that violent barbarian invasions forcibly ended high civilization and reduced the living standards in these regions to those found a thousand years before during the Iron Age.

Ward-Perkins points out the “whys” of this historical revision. Much of it simply has to do with political correctness (which he names as such) — the notion that we cannot really say that one culture is “higher” or “better” than others. Hence, when the one replaces the other, we cannot speculate as to how this replacement made things worse for all involved. In a similar vein, many continental scholars appear to be uncomfortable with the implications that the story of mass barbarian migrations and subsequent destruction and decivilization has in the ongoing discussion about the European Union’s own immigration policy — a discussion in which many of these same academics fall on the left side of the aisle.

Yet, all of this revisionism is bosh and bunkum, as Ward-Perkins so thoroughly points out. He does this by bringing to the table a perspective that many other academics in this field of study don’t have — that of a field archaeologist who is used to digging in the dirt, finding artifacts, drawing logical conclusions from the empirical evidence, and then using that evidence to decide “what really happened”, rather than just literary sources and speculative theories. Indeed, as the author shows, across the period of the Germanic invasions, the standard of living all across Roman western Europe declined, in many cases quite precipitously, from what it had been in the 3rd century. The quality and number of manufactured goods declined. Evidence for the large-scale integrative trade network that bound the western Empire together and with the rest of the Roman world disappears. In its place we find that trade goods travelled much smaller distances to their buyers — evidence for the breakdown of the commercial world of the West. Indeed, the economic activity of the West disappeared to the point that the volume of trade in western Europe would not be matched again until the 17th century. Evidence for the decline of food production suggests that populations fell all across the region. Ward-Perkins’ discussion of the decline in the size of cattle is enlightening evidence that the degeneration of the region was not merely economic. Economic prosperity, the access of the common citizen to a high standard of living with a wide range of creature comforts, disappeared during this period.

The author, however, is not negligent in pointing out the literary and documentary evidence for the horrors of the barbarian invasions that so many contemporary scholars seem to ignore. Indeed, the picture painted by the sum total of these evidences is one of harrowing destruction caused by aggressive, ruthless invaders seeking to help themselves to more than just a piece of the Roman pie. Despite the recent scholarly reconsiderations, the Germans, instead of settling on the land given to them by various Emperors and becoming good Romans, ended up taking more and more until there was nothing left to take. As Ward-Perkins puts it,

Some of the recent literature on the Germanic settlements reads like an account of a tea party at the Roman vicarage. A shy newcomer to the village, who is a useful prospect for the cricket team, is invited in. There is a brief moment of awkwardness, while the host finds an empty chair and pours a fresh cup of tea; but the conversation, and village life, soon flow on. The accommodation that was reached between invaders and invaded in the fifth- and sixth- century West was very much more difficult, and more interesting, than this. The new arrival had not been invited, and he brought with him a large family; they ignored the bread and butter, and headed straight for the cake stand. Invader and invaded did eventually settle down together, and did adjust to each other’s ways — but the process of mutual accommodation was painful for the natives, was to take a very long time, and, as we shall see …left the vicarage in very poor shape. (pp. 82-83)

Professor Bret Devereaux discussed the long fifth century on his blog last year:

… it is not the case that the Roman Empire in the west was swept over by some destructive military tide. Instead the process here is one in which the parts of the western Roman Empire steadily fragment apart as central control weakens: the empire isn’t destroy[ed] from outside, but comes apart from within. While many of the key actors in that are the “barbarian” foederati generals and kings, many are Romans and indeed […] there were Romans on both sides of those fissures. Guy Halsall, in Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West (2007) makes this point, that the western Empire is taken apart by actors within the empire, who are largely committed to the empire, acting to enhance their own position within a system the end of which they could not imagine.

It is perhaps too much to suggest the Roman Empire merely drifted apart peacefully – there was quite a bit of violence here and actors in the old Roman “center” clearly recognized that something was coming apart and made violent efforts to put it back together (as Halsall notes, “The West did not drift hopelessly towards its inevitable fate. It went down kicking, gouging and screaming”) – but it tore apart from the inside rather than being violently overrun from the outside by wholly alien forces.