In The Critic, James Stevens Curl discusses two recent books on the “monuments and monstrosities” of British architecture:

The most startling achievement of the Victorian period was Britain’s urbanisation. By the 1850s the numbers living in rural parts were fractionally down on those in urban areas. By the end of Victoria’s reign more than 75 per cent of the population were town-dwellers, and a romantic nostalgic longing for a lost rural paradise was fostered by those who denigrated urbanisation. This myth of a lost rural ideal led to phenomena such as garden cities and suburbia. Anti-urbanists and critics of the era detested the one thing that gave the Victorian city its great qualities: they were frightened of and hated the Sublime.

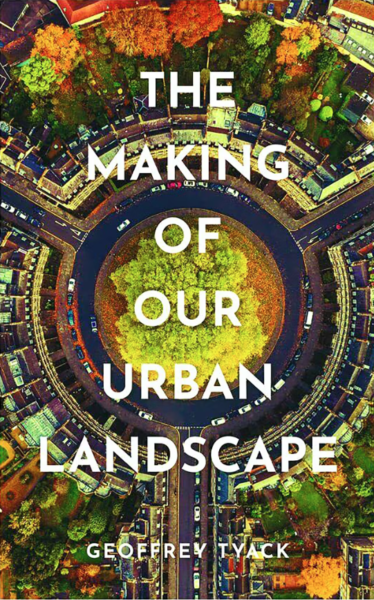

These two books deal with the urban landscape in different ways. Tyack provides a chronological narrative of the history of some British towns and cities spread over two millennia from Roman times to the present day, so his is a very ambitious work. Most towns of modern Britain already existed in some form by 1300, he rightly states, though a few were abandoned, such as Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester) in Hampshire, a haunted place of great and poignant beauty with impressive remains still visible. Most Roman towns were more successful, surviving and developing through the centuries, none more so than London. Tyack describes several in broad, perhaps too broad, terms.

He outlines the creation of dignified civic buildings from the 1830s onwards, reflecting the evolution of local government as power shifted to the growing professional, manufacturing and middle classes: fine town halls, art galleries, museums, libraries, concert halls, educational buildings and the like proliferated, many of supreme architectural importance. Yet the civic public realm has been under almost continuous attack from central government and the often corrupt forces of privatisation for the last half century.

Tyack is far too lenient when considering the unholy alliances between legalised theft masquerading as “comprehensive redevelopment”, local and national government, architects, planners and large construction firms with plentiful supplies of bulging brown envelopes. Perfectly decent buildings, which could have been rehabilitated and updated, were torn down, and whole communities were forcibly uprooted in what was the greatest assault in history on the urban fabric of Britain and the obliteration of the nation’s history and culture.

One of the worst professional crimes ever inflicted on humanity was the application of utopian modernism to the public housing-stock of Britain from the 1950s onwards: this dehumanised communities, spoiled landscapes and ruined lives, yet the architectural establishment remained in total denial. In 1968–72 the Hulme district of Manchester was flattened to make way for a modernist dystopia created by a team of devotees of Corbusianity.

The huge quarter-mile long six-storey deck-access “Crescents” were shabbily named after architects of the Georgian, Regency and early-Victorian periods (Adam, Barry, Kent and Nash). This monstrous, hubristic imposition rapidly became one of the most notoriously dysfunctional housing estates in Europe, a spectacular failure whose problems were all-too-apparent from the very beginning. Yet in The Buildings of England 1969, Manchester was praised for “doing more perhaps than any other city in England … in the field of council housing”. The “Crescents” were recognised quickly as unparalleled disasters and hated by the unfortunates forced to live there. They were demolished in the 1990s, but the creators of that hell were never punished.