World War Two

Published 23 Jul 2022The Allied invasion of Italy powers on and puts the future of a key axis power at play. In the USSR, the Soviets have learnt to deal with German offensives, as the Wehrmacht struggles to make a dent.

(more…)

July 24, 2022

After a Victory at Kursk, The Soviets Attack Everywhere – WW2 – 204 – July 23, 1943

Still no actual evidence of unmarked graves for Residential School children

In Quillette, Jonathan Kay updates the year-old sensational stories about First Nations children being buried in unmarked (in more unhinged reporting it might have been “mass”) graves on the grounds of former Residential Schools in Canada:

Canada’s unmarked-graves story broke on May 27th, 2021, when the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation reported the existence of ground-penetrating radar (GPR) data that indicated regularly spaced subterranean soil disturbances on the grounds of a former Indigenous Residential School that had operated in Kamloops, BC between 1893 and 1978. In addition, the First Nation’s leaders asserted their belief that these soil disturbances corresponded to unmarked graves of Indigenous children who’d died while attending the school.

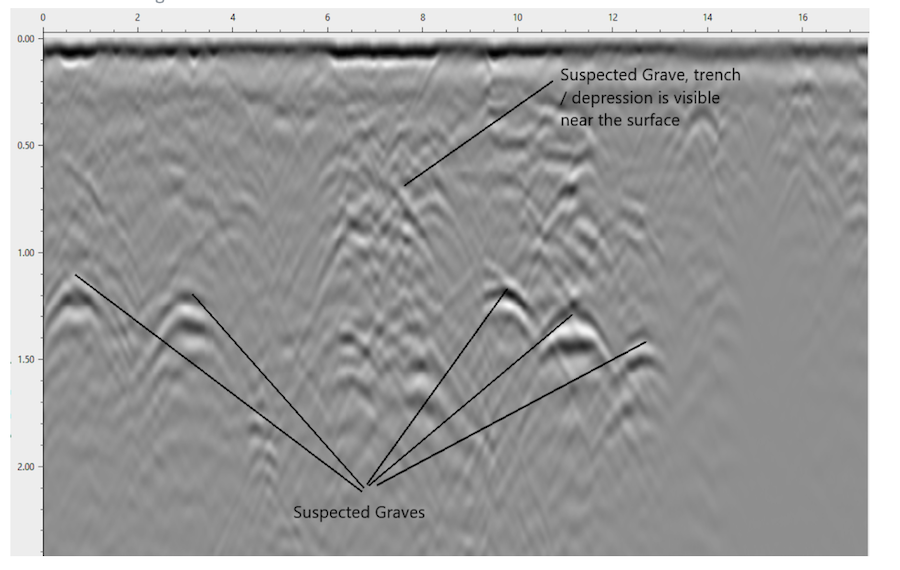

The story became an immediate sensation in the Canadian media; and remained so for months, even after the GPR expert on whom the First Nation relied, Sarah Beaulieu, carefully noted that the radar survey results didn’t necessarily indicate the presence of graves — let alone graves that had been unmarked, graves of Indigenous people, or graves of children. Contrary to what many Canadians came to believe during that heady period, GPR survey data doesn’t yield X-ray-style images that show bodies or coffins. What it typically shows are disruptions in soil and sediment. Investigators then need to dig up the ground to determine what actually lies underneath.

An explanatory image posted by GeoScan, a Canadian Ground-Penetrating-Radar service provider, showing how mapped GPR data can indicate the possible presence of graves.

Image via Quillette.But those details were swept aside during what, in retrospect, appears to have been a true nation-wide social panic. As other Indigenous groups announced that they’d be conducting their own GPR surveys, media figures confidently asserted that the original Canadian Residential-School student death-toll estimate of 3,201 would soon double or even triple. One op-ed writer went so far as to declare that “the discovery of the graves of the children in Kamloops may be Canada’s Holocaust moment.” Dramatic, tear-drenched acts of public atonement unfolded everywhere, with many July 1st Canada Day celebrations being either cancelled or transformed into opportunities for morose self-laceration.

I was one of many Canadians who initially got swept up with all of this — in large part because it seemed as if everyone in the media was speaking with one voice, including journalists I’d known and respected for many years. Looking back on the coverage, I note that headline writers mostly skipped over the technical bits about soil dislocations and such, and went straight to “bodies” and “graves”. And the stories often were interspersed with credulous recitations of dubious tales featuring live babies being thrown into furnaces or buried alive.

The whole mission of Canada’s church-run Residential School system was to assimilate Indigenous people into white Canadian society, usually against their will, while forcing children to leave their families and communities for months or even years at a time. No one disputes that many students were subject to cruel (and sometimes even predatory) treatment and substandard medical care. Certainly, the death rate for Indigenous children attending these schools was much higher than that for children in the general population. No, I never bought into the idea that there was any kind of mass-murder plot going on at these schools. But it hardly seemed far-fetched that some victims of mistreatment and neglect had been buried in unmarked graves — “off the books”, so to speak—by malevolent white teachers, school administrators, and priests seeking to evade responsibility for their actions.

The other important aspect to mention is that — like most other Canadians, I’m guessing — I believed we were only a few days or weeks from seeing real physical evidence plucked from the earth. So it didn’t much matter to me that early commentators were temporarily playing fast and loose with the distinction between GPR data and actual corpses.

Canadians were being told that the old orchard in Kamloops where the GPR data had been collected was a crime scene — a site of mass murder, and the final resting place of 215 child homicide victims. As I’ve reasoned elsewhere: If you told Canadians that, say, 215 murdered white children were buried somewhere in Toronto, or Ottawa, or Vancouver, there’d be investigators and police crawling all over the place, looking for remains that could be tested and identified. And so I naturally assumed the same thing soon would be happening in Kamloops.

But … no. Not at all, in fact.

As I wrote over a year ago, the way the story swept the media was as if the whole Residential School history was somehow new and previously unknown:

Despite being Canadian, my interest in Canadian history centres mostly on economic, naval, and military aspects, but I was certainly aware that the residential school system was a black mark on Canada’s historical dealings with First Nations and that the general outline of events — if not the gruesome details — had been known for many years. The first time I found out about it was in middle school, through what we’d now call a “Young Adult” novel about a young First Nations boy escaping from the residential school he’d been sent to and his attempts to travel hundreds of miles to get home. I read it in the early 70s and it may have been published up to a decade before then (I no longer remember the author’s name or the title of the book, unfortunately).

If I, as a schoolchild, knew something of this fifty years ago, why have people younger than me been shocked and appalled to be hearing about this widespread tragedy for the first time now?

Stoner 63A Automatic Rifle – The Original Modular Weapon

Forgotten Weapons

Published 17 Mar 2018The Stoner 63 was a remarkably advanced and clever modular firearm designed by Eugene Stoner (along with Bob Fremont and Jim Sullivan) after he left Armalite. This was tested by DARPA and the US Marine Corps in 1963, and showed significant potential — enough that the US Navy SEALs adopted it and kept it in service into the 1980s. It was a fantastic balance of weight and controllability, offering a belt-fed 5.56mm platform at less than half the weight of the M60. The other fundamental characteristic of the Stoner 63 was modularity. It was built around a single universal receiver component which could be configured into a multitude of different configurations, from carbine to medium machine gun. Today we have one of the rarer configurations, an Automatic Rifle type. In addition, today’s rifle is actually a Stoner 63A, the improved version introduced in 1966 to resolve some of the problems that had been found in the original.

Ultimately, the Stoner system was able to achieve its remarkably light weight by sacrificing durability. The weapon was engineered extremely well and was not a danger to itself (like, for example, the FG-42), but it was prone to damage when mishandled by the average grunt. This would limit its application to elite units like the SEALs, who were willing to devote the necessary care to the maintenance and operation of the guns in exchange for the excellent handling characteristics it offered.

(more…)

QotD: British armour from BAOR to the first Gulf War

During the Cold War there was a clear threat in the form of the Soviet 3rd Shock Army, which was lined up, facing off against BAOR [British Army of the Rhine] units. It made an enormous amount of sense to contribute to a NATO operation to deter Moscow from chancing their luck, and ensure that they could not force the border and take over Western Germany.

To that end generations of British soldiers were stationed there training for a war that they hoped would never come. To this day there are still serving Cold War veterans who even into the late 1980s knew where they would deploy to, and the likely exact spot in the field or woods where they would dig their trenches and realistically be killed.

This force though was essentially a static one, designed to operate defensively and underpinned by an enormous static logistical and support network stretching from the Inner German Border all the way back to Antwerp and then the UK. The British Army was able to sustain armour in large numbers in part because it had the threat to face, the space to operate and the support network in place to enable this to occur. To this day the subject of how well supported BAOR was through the extensive rear communications zone efforts, and the widespread workshops (such as in Belgium) designed to repair and support UK units is not widely known or told, but deserves much greater recognition.

This matters because when people look back to the size of the British Army in 1990 and look at how many tanks we had then compared to now, they forget that the Army’s MBT capability was essentially a static garrison force waiting to conduct a defensive campaign against a peer threat where it expected to take heavy losses and probably operate very quickly in an NBC environment. It was not intended to be a deployable force capable of operating across the planet on an enduring basis.

This is why when people talk about how many tanks were deployed in 1991 to the Gulf War (some 220 Challenger 1’s were deployed) they forget that this was the first time since Suez that the UK had operated heavy armour overseas. It took many months to get this force into place, and it came at the cost of gutting the operational capability of the remaining BAOR units, who found their logistical support chains hammered in order to support the forces assigned to GRANBY.

The harsh, and perhaps slightly uncomfortable reality for the UK is that OP GRANBY required nearly 6 months of build up at the cost of gutting wider armoured warfare capability – proving that away from home, having 900 tanks is irrelevant if you are operating outside normal parameters and are having to effectively cannibalise or mothball most of them to keep 220 in the Gulf.

By contrast OP TELIC saw over 100 tanks deployed, but a significantly shorter lead in time for the deployment – testament to the significant investments made in the intervening period in logistical capabilities.

Sir Humphrey, “Tanks for nothing — Why it does not matter if the British Army has fewer tanks than Cambodia”, Thin Pinstriped Line, 2019-04-24.