Christopher Snowden on a media-genic “study” from a few years ago that supported the priors of the anti-alcohol campaigners and thus was given full uncritical media coverage, despite obvious flaws in data selection and methodology:

In 2018, the Lancet published a study from the “Global Burden of Disease Alcohol Collaborators” which claimed that there was no safe level of alcohol consumption. This was widely reported and was naturally welcomed by anti-alcohol campaigners. The BBC reported it under the headline “No alcohol safe to drink, global study confirms”. (Note the cheeky use of the word confirms, despite the finding going against fifty years of evidence.)

The study wasn’t based on any new epidemiology. Instead it took crude, aggregate data from almost every country in the world, mashed it together and attempted to come up with a global risk curve.

The study contains no new evidence and uses an unusual modelling approach based on population-wide data from various online sources. If you look at this massive appendix you can see the kind of data they were using. The figures are extremely crude.

The authors don’t dispute the benefits of moderate drinking for heart disease but they claim that the benefits are matched by risks from other diseases at low levels of consumption and are outweighed by the risks at higher levels of consumption. Some diseases which have been associated with benefits of drinking, such as dementia, are excluded from the analysis entirely. They also ignore overall mortality, which you might think was kind of important.

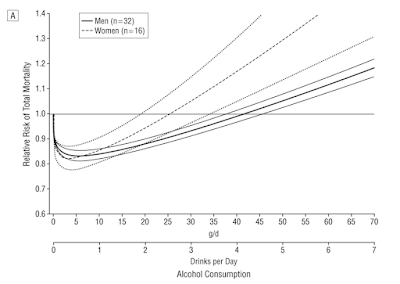

A typical risk curve for alcohol consumption and mortality is J-shaped. It looks like this …

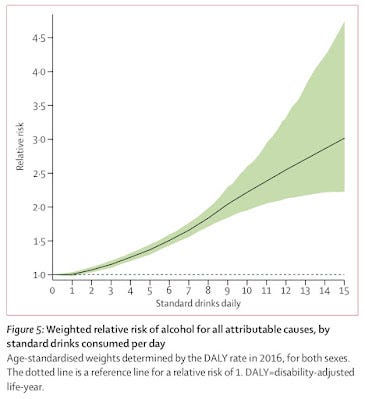

But the GBD’s risk curve for “all attributable causes” looked like this…

You will notice that there appears to be no protective effect at moderate rates of consumption in the GBD’s curve. One important reason for this is that they associate alcohol consumption at any level with tuberculosis. Tuberculosis remains a serious health problem in much of the world, but not in Britain. So what relevance does a global risk curve have to us? None.

Moreover, TB is not really an alcohol-related disease and is only viewed as such in this study because (a) drinking might weaken the immune system and (b) people who go to bars and clubs are more likely to catch an infectious disease. I kid you not.