Joel Kotkin looks at the first round results of the French Presidential election and wonders how long the working classes are going to put up with everything the elites dish out:

Whatever the final outcome, the recent French elections have already revealed the comparative irrelevance of many elite concerns, from genderfluidity and racial injustice to the ever-present “climate catastrophe”. Instead, most voters in France and elsewhere are more concerned about soaring energy, food and housing costs. Many suspect that the cognitive elites, epitomised by President Emmanuel Macron, lack even the ambition to improve their living conditions.

The French elections reflect the essential political conflict of our time. On one side, there is a powerful alliance between the corporate oligarchy and the regulatory clerisy. On the other, there are two beleaguered and angry classes – the small-business owners and artisans, and the vast, largely unorganised service class. The small-business class generally tends to favour the populist right, whether in America, Australia or Europe. These people want the government out of their business and to be left alone. Meanwhile, workers tend towards the populist left, which promises to relieve their economic pain.

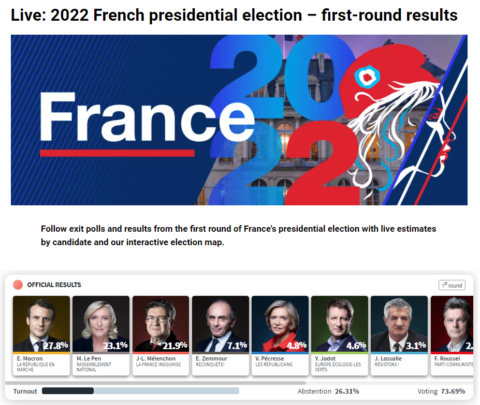

The common feature is the politics of anger and resentment. In the first round of the French elections, a majority voted either for Marine Le Pen and other rightist candidates, or for the old Trotskyist warhorse Jean-Luc Mélenchon and other candidates of the hard left. The establishment parties, like the centre-left Parti Socialiste and the Gaullist Républicains, were left way behind. The ultra-green Parti Socialiste mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, won less than two per cent – a pathetic performance from the onetime ruling party. Intriguingly, voters under 35 went first for Mélenchon and then Le Pen, leaving the technocrat Macron in dismal third place among the young. Macron only won decisively among voters over 60.

We may, as de Tocqueville put it during the early stages of the Industrial Revolution, be “sleeping on a volcano”. A still inchoate rebellion from below against the concentration of wealth and power above seems to be gathering momentum. Across the 36 wealthier countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the richest citizens have taken an ever-greater share of national GDP in recent years as the middle class has become smaller. Heavily in debt, mainly because of high housing costs, the middle class “looks increasingly like a boat in rocky waters”, suggests the OECD.

One key indicator of the declining middle class is rates of home ownership, which are stagnant or plummeting, particularly among the young, in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. In the United States, the chance of middle-class earners moving up to the top rungs of the earnings ladder has dropped by approximately 20 per cent since the early 1980s. Life expectancy in the US has dropped to the lowest levels in a quarter of a century.